My father’s strength, moral and physical, dominated the early part of my life. He had a massive back and a barrel chest, and although he was quite short he communicated indomitability and, at least to me, a sense of overpowering confidence. His most striking physical feature was his ramrod-stiff, nearly caricature-like upright carriage. And with that, in contrast to my shrinking, nervous timidity and shyness, went a kind of swagger that furnished another browbeating contrast with me: he never seemed to be afraid to go anywhere or do anything. I was, always. Not only did I not rush forward as I should have done in school games, but I felt seriously unwilling to let myself be looked at, so conscious was I of innumerable physical defects, all of which I was convinced reflected my inner deformations. To be looked at directly, and to return the gaze, was most difficult for me. When I was about ten I mentioned this to my father. ‘Don’t look at their eyes; look at their nose,’ he said, thereby communicating to me a secret technique I have used for decades. When I began to teach as a graduate student in the late fifties I found it imperative to take off my glasses in order to turn the class into a blur that I couldn’t see. And to this day I find it unbearably difficult to look at myself on television, or even read about myself.

It was my mother’s often melting warmth which offered me a rare opportunity to be the person I felt I truly was, in contrast to the ‘Edward’ who failed at school and sports, and could never match the manliness my father represented. And yet my relationship with her grew more ambivalent, and her disapproval of me became far more emotionally devastating than my father’s virile bullying and reproaches. One summer afternoon in Lebanon when I was sixteen and in more than usual need of her sympathy, she delivered a judgement on all her children that I have never forgotten. I had just spent the first of two unhappy years at Mount Hermon, a repressive New England boarding school, and this particular summer of 1952 was critically important, mainly because I could spend time with her. We had developed the habit of sitting together in the afternoons, talking quite intimately, exchanging news and opinions. Suddenly she said, ‘My children have all been a disappointment to me. All of them.’ Somehow I couldn’t bring myself to say, ‘But surely not me,’ even though it had been well established that I was her favourite, so much so (my sisters told me) that during my first year away from home she would lay a place for me at table on important occasions like Christmas Eve, and would not allow Beethoven’s Ninth (my preferred piece of music) to be played in the house.

‘Why,’ I asked, ‘why do you feel that way about us?’ She pursed her lips and withdrew further into herself, physically and spiritually. ‘Please tell me why,’ I continued. ‘What have I done?’

‘Some day perhaps you will know, maybe after I die, but it’s very clear to me that you are all a great disappointment.’ For some years I would re-ask my questions, to no avail: the reasons for her disappointment in us, and obviously me, remained her best-kept secret, as well as a weapon in her arsenal for manipulating us, keeping us off balance, and me at odds with my sisters and the world. Had it always been like this? What did it mean that I had once believed our intimacy was so secure as to admit few doubts and no undermining at all of my position? Now as I looked back on my frank and, despite the disparity in age, deep liaison with my mother, I realised how her critical ambivalence had always been there.

Hilda, my mother, was born in Nazareth in 1914, the middle child of five, and she was Palestinian, even though her mother was Lebanese. Her father was the Baptist minister in Nazareth. She was sent to boarding school in Beirut, the American School for Girls, a missionary institution that tied her to Beirut first and last, with Cairo a long interlude between. Undoubtedly a star there and at junior college (now the Lebanese American University), she was popular and brilliant – first in her class – in most things. Then, in 1932, she was plucked from what was – or was retrospectively embellished as – a wonderful life and returned from Beirut to dour, old Nazareth, where she was deposited into an arranged marriage with my father, who was at least nineteen years her senior.

My father, Wadie, never told me more than ten or eleven things about his past, all of which never changed and remained hardly more than a series of set phrases. He was born in Jerusalem in 1895 (my mother said it was more likely 1893), which made him at least forty at the time of my birth. He hated Jerusalem, and although I was born and we spent long periods of time there, the only thing he ever said about it was that it reminded him of death. At some point in his life his father was a dragoman who because he knew German had, it was said, shown Palestine to Kaiser Wilhelm. And my grandfather – never referred to by name except when my mother, who never knew him, called him Abu-Asaad – bore the surname Ibrahim. In school, therefore, my father was known as Wadie Ibrahim. I still do not know where ‘Said’ came from, and no one seems able to explain it. The only relevant detail about his father that my father thought fit to convey to me was that Abu-Asaad’s whippings were much severer than his of me. ‘How did you endure it?’ I asked, to which he replied with a chuckle, ‘Most of the time I ran away.’ I was never able to do this, and never even considered it.

Today none of us can fully grasp what my parents’ marriage was or how it came about, but I was trained by my mother – my father being generally silent on that point – to see it as something difficult at first, to which she gradually adjusted over the course of nearly forty years, and which she transformed into the main event of her life. She never worked or really studied again, and she never spoke about sex without shuddering dislike and discomfort, although my father’s frequent remarks about the man being a skilled horseman, the woman a subdued mare, suggested to me a basically reluctant, if also exceptionally fruitful, sexual partnership that produced six children.

But I never doubted that at the time of her marriage to this silent and peculiarly strong middle-aged man she suffered a terrible blow. She was wrenched from a happy life in Beirut. She was given to a much older spouse – perhaps in return for some sort of payment to her mother – who promptly took her off to strange parts and then set her down in Cairo, a gigantic and confusing city in an unfamiliar Arab country. My parents often returned to my father’s family home in Jerusalem – once for my birth, in 1935 – but Cairo was where my father had his business (office equipment and stationery), and it was where, mostly, I grew up.

In 1937, when I was two, my parents moved to Zamalek, an island in the Nile between the city of Cairo in the east and Giza in the west, inhabited by foreigners and wealthy locals. Zamalek was not a real community but a sort of colonial outpost whose tone was set by Europeans with whom we had little or no contact: we built our own world within it. Our house was a spacious fifth-floor apartment at 1 Sharia Aziz Osman that overlooked the so-called Fish Garden, a small, fence-encircled park with an artificial rock hill (gabalaya), a tiny pond and a grotto; its little green lawns were interspersed with winding paths, great trees and, in the gabalaya area, artificially made rock formations and sloping hillsides where you could run up and down without interruption. Except for Sundays and public holidays the Garden, as we called it, was where I spent all of my playtime, always unsupervised and always within range of my mother’s voice, which was lyrically audible to me and my sisters.

I played Robinson Crusoe and Tarzan there, and when my mother came with me, I played at eluding and then rejoining her. She went nearly everywhere with us, throughout our little world, one little island enclosed by another one. In the early years we went to school a few blocks away from the house – GPS, Gezira Preparatory School, which I attended from the autumn of 1941 till we left Cairo in May 1942, then again from early 1943 till 1946, with one or two longer Palestinian interruptions in between. For sports there was the Gezira Sporting Club and, on weekends, the Maadi Sporting Club, where I learned to swim. For years, Sundays meant Sunday school; this senseless ordeal occurred between nine and ten in the morning at the GPS, followed by matins at All Saints’ Cathedral. Sunday evenings took us to the American Mission Church in Ezbekieh, and two Sundays out of three to evensong at the cathedral. School, church, club, garden, house – a limited, carefully circumscribed segment of the great city – was my world until I was well into my teens.

During the GPS years I began slowly, almost imperceptibly, to develop a contestatory relationship with two of my younger sisters, Rosy and Jean, which played or was made to play into my mother’s skills at managing and manipulating us. I had felt protective of Rosy: I helped her along, since she was somewhat younger and less physically adept than I; I cherished her and would frequently embrace her as we played on the balcony; I kept up a constant stream of chatter, to which she responded with smiles and chuckles. We went off to GPS together in the morning, but we separated once we got there since she was in a younger class. She had lots of giggling little girlfriends – Shahira, Nazli, Nadia, Vivette – and I, my ‘fighting’ classmates such as Dickie Cooper or Guy Mosseri. Quickly she established herself as a ‘good’ girl, while I lurked about the school with a growing sense of discomfort, rebelliousness, drift and loneliness.

After school the troubles began between us. They were accompanied by our enforced physical separation: no baths together, no wrestling or hugging, separate rooms, separate regimens, mine more physical and disciplined than hers. When Mother came home she would discuss my performance in contrast to my younger sister’s. ‘Look at Rosy. All the teachers say she’s doing very well.’ Soon enough, Jean – exceptionally pretty with her thick, auburn pigtails – changed from a tag-along younger version of Rosy into another ‘good’ girl, with her own circle of apparently like-minded girlfriends. And she also was complimented by the GPS authorities, while I continued to sink into protracted ‘disgrace’, an English word that hovered around me from the time I was seven. Rosy and Jean occupied the same room; I was down the corridor; my parents in between; Joyce and Grace (eight and eleven years younger than I) had their bedrooms moved from the glassed-in balcony to another room as the apartment was modified to accommodate the growing children.

The closed door of Rosy and Jean’s room signified the definitive physical as well as emotional gulf that slowly opened between us. There was once even an absolute commandment against my entering the room, forcefully pronounced and occasionally administered by my father, who now openly sided with them, as their defender and patron; I gradually assumed the part of their dubiously intentioned brother. ‘Protect them,’ I was always being told, to no effect whatever. For Rosy especially I was a sort of prowling predator-target, to be taunted or cajoled into straying into their room, only to be pelted with erasers, hit over the head with pillows, and shrieked at with terror and dangerous enjoyment. They seemed eager to study and learn at school and home, whereas I kept putting off such activities in order to torment them or otherwise fritter away the time until my mother returned home to a cacophony of charges and countercharges buttressed by real bruises to show and real bites to be cried over.

There was never complete estrangement though, since the three of us did at some level enjoy the interaction of competing, but rarely totally hostile, siblings. My sisters could display their quickness or specialised skill in hopscotch, and I could try to emulate them; in memorable games of blind man’s buff, ring-around-the-rosy, or clumsy football in a very confined space, I might exploit my height or relative strength. After we attended the Circo Togni, whose lion tamer especially impressed me with his authoritative presence and braggadocio, I replicated his act in the girls’ room, shouting commands like ‘A posto, Camelia! ’ at them while waving an imaginary whip and grandly thrusting a chair in their direction. They seemed quite pleased at the charade, and even managed a dainty roar as they clambered onto bed or dresser with not quite feline grace.

But we never embraced each other, as brothers and sisters might ordinarily have: for it was exactly at this subliminal level that I felt a withdrawal on all sides, of me from them, and them from me. The physical distance is still there between us, I feel, perhaps deepened over the years by my mother. When she returned from her afternoons at the Cairo Women’s Club she invariably interjected herself between us. With greater and greater frequency my delinquency exposed me to her angry reprobation: ‘Can’t I ever leave you with your sisters without your making trouble?’ was the refrain, often succeeded by the dreaded codicil, ‘Wait till your father gets home.’ Precisely because there was an unstated prohibition on physical contact between us, my infractions took the form of attacks that included punching, hair-pulling, pushing, and the occasional vicious pinch. Invariably I was ‘reported’ and then ‘disgraced’ – in English – and some stringent punishment (a further prohibition on going to the movies, being sent to bed without dinner, a steep reduction in my allowance and, at the limit, a beating from my father) was administered.

All this heightened our sense of the body’s peculiar, and problematic, status. There was an abyss – never discussed nor examined, nor even mentioned during the crucial period of puberty – separating a boy’s body from a girl’s. Until I was twelve I had no idea at all what sex between men and women entailed, nor did I know very much about the relevant anatomy. Suddenly, however, words like ‘pants’ and ‘panties’ became italicised: ‘I can see your pants,’ said my sisters tauntingly to me, and I responded, heady with danger, ‘I can see your panties.’ I quite clearly recall that bathroom doors had to be bolted shut against marauders of the opposite sex, although my mother was present for both my dressing and undressing, as well as for theirs. I think she must have understood sibling rivalry very well and the temptations of polymorphous perversity all around us. But I also suspect that she played and worked on these impulses and drives: she kept us apart by highlighting our differences, she dramatised our shortcomings to each other, she made us feel that she alone was our reference point, our most trusted friend, our most precious love as, paradoxically, I still believe she was. Everything between me and my sisters had to pass through her, and everything I said to them was steeped in her ideas, her feelings, her sense of what was right or wrong.

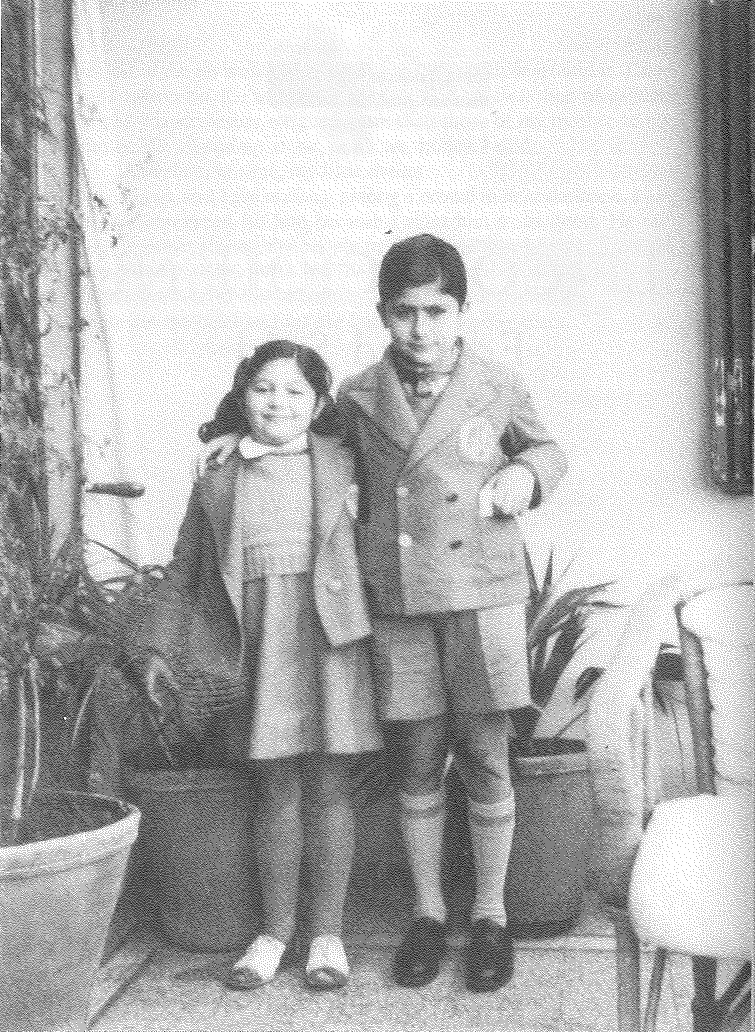

Edward, aged seven, with his sister Rosy in Gezira Preparatory School uniform, 1943

None of us of course ever knew what she really thought of us, except fleetingly, enigmatically, alienatingly (as when she told me that we had all been a disappointment to her). It was only much later in my life that I understood how unfulfilled and angry she must have felt about our life in Cairo; its busy conventionality, forced rigours and the peculiar lack of authenticity. She had a fabulous capacity for letting you trust and believe in her, even though you knew that a moment later she could either turn on you with incomparable anger and scorn or draw you in with her radiant charm. ‘Come and sit next to me, Edward,’ she would say, inviting you into her confidence, and allowing you an amazing sense of assurance; of course, you also felt that by doing this she was keeping out Rosy and Jean, even my father then, as well.

But who was she really? Unlike my father, whose general solidity and lapidary pronouncements were a known and stable quantity, my mother was energy itself, all over the house and our lives, ceaselessly probing, judging, sweeping all of us, plus our clothes, rooms, hidden vices, achievements and problems into her always expanding orbit. But there was no common emotional space. Instead there were bilateral relationships with my mother, as colony to metropole, a constellation only she could see as a whole. What she said to me about herself, for instance, she also said to my sisters, and this characterisation formed the basis of her operating persona: she was simple, she was a good person who always did the right things, she loved us all unconditionally, she wanted us to tell her everything. I believed this unquestioningly. There was nothing so satisfying in the outside world, a merry-go-round of changing schools (and hence friends and acquaintances), in which, as a non-Egyptian of uncertain, not to say suspicious, composite identity, I felt habitually out of place. My mother seemed to take in and sympathise with my general predicament. And that was enough for me. It worked as a provisional support, which I cherished tremendously.

It was through my mother that I grew more aware of my body as incredibly fraught and problematic, first because in her intimate knowledge of it she seemed better able to understand its capacity for wrongdoing, and second because she would never speak openly about it, but approached the subject either with indirect hints or, more troublingly, by means of my father and maternal uncles, through whom she spoke like a ventriloquist. When I was about fourteen I said something she thought was tremendously funny; I did not realise at the time how astute I was. I had left the bathroom door unlocked (a telling inadvertence, since I had gained some privacy as an adolescent, but for some reason wanted it occasionally infringed upon), and she suddenly entered. For a second she didn’t close the door, but stood there surveying her naked son as he hastily dried himself with a small towel. ‘Please leave,’ I said testily, ‘and stop trying to catch up where you left off.’ She burst out laughing, quickly closed the door, and walked briskly away. Had she ever really left off ?

I knew much earlier that my body and my sisters’ were inexplicably taboo. My mother’s ambivalence expressed itself in her extraordinary physical embrace of her children – covering us with kisses, caresses and hugs, cooing, making expostulations of delight about our beauty and physical endowments – and at the same time offering a great deal of devastating negative commentary on our appearance. Fatness was a dangerous and constant subject when I was nine and Rosy was seven. As my sister gained weight it became a point of discussion for us throughout childhood, adolescence and early adulthood. Along with that went an amazingly detailed consciousness of ‘fattening’ foods, plus endless prohibitions. I was quite skinny, tall, coordinated; Rosy didn’t seem to be, and this contrast between us, to which was added the contrast between her cleverness at school and my shabby performance there, my father’s special regard for her versus my mother’s for me (they always denied any favouritism), her greater savoir faire when it came to organising her time, and her capacity for pacing herself, talents I did not at all possess – all this deepened the estrangement between us, and intensified my discomfort with our bodies.

It was my father who gradually took the lead in trying to reform, perhaps even to remake, my body, but my mother rarely demurred, and regularly brought my body to a doctor’s attention. As I look back on my sense of my body from age eight on, I can see it locked in a demanding set of repeated corrections, all of them ordered by my parents, most of them having the effect of turning me against myself. ‘Edward’ was enclosed in an ugly, recalcitrant shape with nearly everything wrong with it. Until the end of 1947, when we left Palestine for the last time, our paediatrician was a Dr Grünfelder, a German Jew, and known to be the finest child-doctor in Palestine. His office was in a quiet and leafy area of the parched city that seemed distinctly foreign to me then. He spoke to us in English, although there was a good deal of confidential whispering between him and my mother that I was rarely able to overhear. Three persistent problems were referred to him, for which he provided his own idiosyncratic solutions; the problems themselves indicate the extent to which certain parts of my body came in for an almost microscopic, and needlessly intense, supervision.

One concerned my feet, which were pronounced flat early in my life. Grünfelder prescribed the metal arches that I wore with my first pair of shoes; they were finally discarded in 1948, when an aggressive clerk in a Dr Scholl’s store in Manhattan dissuaded my mother from their use. A second was my odd habit of shuddering convulsively for a brief moment every time I urinated. My mother observed me for a couple of weeks, then brought the case to the world-renowned ‘child specialist’. Grünfelder shrugged his shoulders. ‘It is nothing,’ he pronounced, ‘probably psychological’ – a phrase I didn’t understand but could see worried Mother just a little more, or was at least to worry me until I was well into my teens, after which the issue was dropped.

The third problem was my stomach, the source of numerous ills and pains all my life. It began with Grünfelder’s scepticism about my mother’s habit of wrapping and tightly pinning a small blanket around my midsection in both summer and winter. She thought this protected me against illness, the night air, perhaps even the evil eye; later, hearing about it from different friends, I realised it was common practice in Palestine and Syria. She once told Grünfelder about this strange prophylactic in my presence, his response to which I distinctly remember was a knitted brow. ‘I don’t see the need,’ he said, whereupon she pressed on with a rehearsal of all sorts of advantages (most of them preventive) that accrued to me. I was nine or ten at the time. The issue was also debated with Wadie Baz Haddad, our family GP in Cairo, and he too tried to dissuade her. It took another year for the silly thing to be removed once and for all; my mother later told me that still another doctor had warned her against sensitising my midsection so much, since it then became vulnerable to all sorts of other problems.

My eyes had grown weaker because I had spring catarrh and a bout of trachoma; for two years I wore dark glasses at a time when no one else did. At age six or seven, I had to lie in a darkened room every day with compresses on my eyes for an hour. As my short-sightedness developed I saw less and less well, but my parents took the position that glasses were not ‘good’ for you, and were positively bad if you ‘got used’ to them. In December of 1949 at the age of fourteen, I went to see Arms and the Man at the American University of Cairo’s Ewart Hall, and was unable to follow the action on stage, until a friend loaned me his glasses. Six months later, after a teacher’s complaint, I did get glasses with express parental instructions not to wear them all the time: my eyes were already bad enough, I was told, and would get worse.

At the age of twelve I was informed that the pubic hair sprouting between my legs was not ‘normal’, increasing my already overdeveloped embarrassment about myself. The greatest critique, however, was reserved for my face and tongue, back, chest, hands and abdomen. I did not know I was being attacked, nor did I experience the reforms and strictures as the campaigns they were. I assumed they were all elements of the discipline that one went through as part of growing up. The net effect of these reforms, however, was to make me deeply self-conscious and ashamed.

The longest-running and most unsuccessful reform – my father’s near obsession – concerned my posture, which became a major issue for him just as I reached puberty. In June 1957, when I graduated from Princeton, it culminated in my father’s insisting on taking me to a brace and corset maker in New York in order to buy me a harness to wear underneath my shirt. What still distresses me about the experience is that at the age of twenty-one I uncomplainingly let my father feel he was entitled to truss me up like a naughty child whose bad posture symbolised some objectionable character trait that required scientific punishment. The clerk who sold us the truss remained expressionless as my father amiably declared, ‘See, it works perfectly. You’ll have no problems.’

The white cotton and latex truss with straps across my chest and over the shoulders was the consequence of years of my father trying to get me to ‘stand up straight’. ‘Shoulders back,’ he would say, ‘shoulders back,’ and my mother – whose own posture, like her mother’s, was poor – would add in Arabic, ‘Don’t slump.’ As the offence persisted she resigned herself to the notion that my posture came from the Badrs, her mother’s family, and would routinely emit a desultory sigh, fatalistic and disapproving at the same time, followed by the phrase ‘Herdabit beit Badr’, or ‘the Badr family humpback’, addressed to no one in particular, but clearly intended to fix the blame on my ancestry, if not also on her.

The Badrs’ or not, my father persisted in his efforts. These later included ‘exercises’, one of which was to slip one of his canes through both my armpits and make me keep it there for two hours at a stretch. Another was to make me stand in front of him and for half an hour respond to the order ‘One’ by thrusting my elbows back as hard and as quickly as possible, supposedly straightening my back in the process. Whenever I wandered across his line of vision he would call out, ‘Shoulders back.’ This of course embarrassed me when others were around, but it took me weeks to ask him to please not call out to me so loudly on the street, in the club, or even walking into church. He was reasonable about my objection. ‘Here’s what I’ll do,’ he said reassuringly. ‘I’ll just say “Back”, and only you and I will know what it means.’ And so ‘Back’ I endured for years and years – until the truss.

A corollary to the struggle over my posture was how it affected my chest, whose disproportionately large size and prominence I inherited from my father. Very early in my teens I was given a metal chest expander with instructions to use it to develop the size and disposition of the front of my body. I was never able to master the gadget’s crazy springs, which leapt out at you threateningly if you did not have the strength to keep them taut. The real trouble, as I once explained to my mother who listened sympathetically, was that my chest was already too large; thrusting it forward aggressively, making it even bigger, turned me into a grotesque, barrel-chested caricature of a well-developed man. I seemed to be caught between the hump and the barrel. My mother understood and tried to persuade my father of this, without any observable result. When he was in America before the First World War my father had been influenced by Eugen Sandow, the legendary strongman who even turns up in Ulysses, and Sandow featured an overdeveloped chest and erect back. What was good for Sandow, my father once told me, ought to do ‘for you too’.

Yet on several occasions my resistance exasperated my father enough for him to pummel me painfully around my shoulders, and once even to deliver a solid fist to my back. He could be physically violent, throwing heavy slaps across my face and neck, while I cringed and dodged in what I felt was a most shameful way. I regretted his strength and my weakness beyond words, but I never responded or called out in protest, not even when, as a Harvard graduate student in my early twenties, I was bashed by him humiliatingly for being rude, he said, to my mother. I learned how to sense that a cuff was on its way by the odd fashion in which he drew his top lip into his mouth and the heavy breath he suddenly took in. I much preferred the studied care he took with my canings – using a riding crop – to the frightening, angry and impulsive violence of his slaps and swinging blows to my face. When she suddenly lost her temper, my mother also flailed at my face and head, but less frequently and with considerably less force.

As I write this now it gives me a chance, very late in life, to record the experiences as a coherent whole that very strangely have left no anger, some sorrow, and a surprisingly strong residual love for my parents. All the reforming things my father did to me coexisted with an amazing willingness to let me go my own way later on; he was strikingly generous to me at Princeton and Harvard, always encouraging me to travel, to continue piano studies, to live well, always willing to foot the bill, even though my journey took me further from him as an only son and the only likely successor in the family business. What I cannot completely forgive, though, is that the contest over my body, and my father’s reforms and physical punishment, instilled a deep sense of generalised fear in me, which I have spent most of my life trying to overcome. I still sometimes think of myself as a coward, with some gigantic lurking disaster waiting to overtake me for sins I have committed and will soon be punished for.

My parents’ fear of my body as imperfect and morally flawed extended to my appearance. When I was about five, my long curly hair was chopped down into a very short no-nonsense haircut. Because I had a decent soprano voice and was considered ‘pretty’ by my doting mother, I felt my father’s disapproval, even anxiety, that I might be a ‘sissy’, a word that hovered around me until I was ten. A strange motif of my early teens was an assault on the ‘weakness’ of my face, particularly my mouth. My mother used to tell two favourite stories; the first was about how Leonardo da Vinci used the same man as a model for Jesus and, after years of the man’s dissipation, for Judas. The other had her quoting Lincoln, who, after condemning a man for his awful looks and being challenged by a friend that no one is responsible for being ugly, was reported to have responded, ‘Everyone is responsible for his face.’ When I was being upbraided for delinquency against my sisters, or for lying about having eaten all the candy, or for having spent all my money, my father would swiftly thrust his hand out, put his thumb and second finger on either side of my mouth, press in, and hold the area with a number of energetic short jerks to the left and right, all the while producing a nasty, buzzing sound like ‘mmmmm’, quickly followed by ‘that weak mouth of yours’. I can recall staring at myself disgustedly in the mirror well past my twentieth birthday, doing exercises (pursing my mouth, clenching my teeth, raising my chin twenty or thirty times) in an effort to bring ‘strength’ to my weak droop. Glenn Ford’s way of flexing his jaw muscles to signify moral fortitude was an early model, which I tried to imitate when responding to my parents’ accusation. It was partly because of my weak face and mouth that my parents disapproved of my wearing glasses; my mother, ever ready to condemn and praise at the same time, stipulated that glasses obscured ‘that beautiful face of yours’.

As for my torso, there wasn’t much said about it until I was thirteen, a year before I went to Victoria College in 1949. My father met a gentleman at the Gezira Club called Mr Mourad who had just opened a gymnasium in an apartment on Fuad al-Awwal Street in Zamalek, about half a mile from where we lived. Soon after I found myself enrolled in three exercise classes a week, along with half a dozen Kuwaitis who had come to Egypt to attend the university. These classes included knee bends, medicine-ball raises and lifts, sit-ups, jogging and jumping (all inside a tiny circular room). I was soon the butt of our wiry instructor, Mr Ragab. ‘More effort,’ he would call out hectoringly at me in English–’Up, down, up, down,’ etc. Then, a few weeks into the course, came the bombshell. ‘Come on, Edward,’ he said contemptuously of my sit-ups, ‘we must get that stomach of yours into shape.’ When I said that I thought the purpose of my being at the gym was my back, he said that it was, but my midsection was not firm enough. ‘Anyway, it’s what your parents want us to do.’ I was too embarrassed ever to raise the matter with my parents. Another tear opened in the relationship to my body. And as I accepted the verdict I internalized the criticism, and became even more awkward about and uncertain of my physical identity.

My problematic hands became my mother’s special province of critical attention. Although I was only dimly aware that physically I noticeably resembled neither the Saids (short, stocky, very dark) nor her family, the Musas (white-skinned, of medium height and build, with longer than average fingers and limbs), it was clear to me that I had endowments of strength and athletic ability denied anyone else. By the age of twelve I was a good deal taller than everyone else in my family, and, thanks to my father’s curious persistence, I had amassed knowledge and practice of numerous sports, including tennis, swimming, football (despite my noted failure at it), riding, track and field, cricket, ping-pong, sailing, boxing. I was never outstanding in any of them, being too timid to dominate an opponent, but I had developed an already considerable natural competence. This allowed me over time to develop my strength, certain muscles, and–something I still possess–a very unusual stamina and wind. My hands in particular were large, exceptionally sinewy, and agile. And to my mother, they represented objects both of adoring admiration (the long, tapered fingers, the perfect proportions, the superb agility) and of often quite hysterical denunciation (‘Those hands of yours are deadly instruments’; ‘They’re going to get you into trouble later’; ‘Be very careful’.)

To my mother they were almost everything except a pair of hands: they were hammers, pliers, clubs, steel wires, nails, scissors, and when she wasn’t angry or agitated, instruments of the most refined and gentle kind. For my father my hands were noteworthy for the fingernails’, which I chewed on and which for decades he tried to get me not to chew, even to the point of having them painted with a vile-tasting medicine and to promising me a fancy manicure at Chez Georges, the plush barbershop he frequented on Kasr el Nil Street. All to no avail, though I often found myself hiding my hands in my pockets, as I tried not to expose myself to my father’s gaze so that my ‘back’ would not obtrusively draw his, and everyone else’s, attention.

The moral and the physical shaded into each other most imperceptibly of all when it came to my tongue, which was the object of a dense series of metaphorical associations in Arabic, most of which were negative and, in my particular case, recurred with great frequency. In English one hears mainly of a ‘biting’ or ‘sharp’ tongue, in contrast with a ‘smooth’ one. Whenever I blurted out something that seemed untoward, it was my ‘long’ tongue that was to blame: aggressive, unpleasant, uncontrolled. The description was a common one in Arabic and signified someone who did not have the required politeness and verbal savoir faire, important qualities in most Arab societies. It was my state of being repressed that caused these occasional outbursts as I compensated too much in the wrong direction. In addition, I violated all sorts of codes for the proper way to address parents, relatives, elders, teachers, brothers and sisters. This was noted by my mother, who would escalate my offence into a portent of truly dire things to come. Added to that, I was also singularly unable to keep secrets or to do what everyone else did by way of choosing what not to say. In the context of Arabic, therefore, I was regarded as outside the range of normal behaviour, a rogue creature of whom other people should be wary.

Perhaps the real issue was sex, or, rather, my parents’ defence against its onset in my life and, when it could no longer be staved off, its taming. Even when I left for the United States in 1951 at fifteen, my existence had been completely virginal, my acquaintance with girls non-existent. Movies like The Outlaw, Duel in the Sun, even the Michèle Morgan costume drama Fabiola, which I desperately wanted to see, were forbidden as being ‘not for children’; such bans existed until I was fourteen. There were no visibly available sex magazines or pornographic videos in those days; the schools I went to in Egypt or the States until I was seventeen and a half infantilized and desexualized everything. This was also true of Princeton, which I attended until I was twenty-one. Sex was banned everywhere, including books, although there my inquisitiveness and the large number of volumes in our library made complete prohibition impossible to enforce. It was my own powerful need to know and experience that broke through my parents’ restrictions, until an open confrontation took place whose memory, forty-six years later, still makes me shudder.

One chilly Sunday afternoon in late November 1949, at three o’clock, a few weeks after I had turned fourteen, there was a loud knock on my bedroom door, followed immediately by a sternly authoritative wrenching of the handle. This was very far from a friendly parental visit. My father stood near the door for a moment; in his right hand he distastefully clutched my pyjama bottoms, which I despairingly remembered I had left in the bathroom that morning. I held out my hands to catch the offending article, expecting him as he had done once or twice before to scold me for leaving my things around (‘Please put them away; don’t leave them for someone else to pick up’). The servants, he would add, were not for my personal comfort.

Since he kept the garment in his hand I knew that this must be a more serious matter, and I sank back into the bed, anxiously awaiting the attack. When he was halfway into the room, just as he began to speak, I saw my mother’s drawn face framed in the doorway several feet behind him. She said nothing but was there to give emotional weight to his prosecution of the case. ‘Your mother and I have noticed’ – here he waved the pyjamas – ’that you haven’t had any wet dreams. That means you’re abusing yourself.’ He had never said it accusingly before, although the dangers of ‘self-abuse’ and the virtues of wet dreams had been the subject of several lectures and were first described to me on a walk around the deck of the Saturnia en route to New York in July of 1948.

These lectures were the result of my asking my mother about a stout little pair of Italian opera singers, fellow passengers on the Saturnia. She wore very high heels, a tight white dress, heavily painted lips; he was in a shiny brown suit, elevated heels, with carefully slicked-back hair; both exuded a bountiful sexuality to which I could attach no specific practices. In an unguarded moment I had asked my mother confusedly and inarticulately how such people as those actually did ‘it’. I had no words for ‘it’, none for penis or vagina, and none for foreplay; all I could do was to enlist urination and defecation in my question, which, I had somehow gleaned, bore some pleasurable meaning as well. My mother’s look of alarm and disgust set me up for the ‘man-to-man’ talk with my father. A great part of his massive authority, and his compelling power over me, was that strange combination of silence and the ritual repetition of clichés picked up from assorted places – Tom Brown’s Schooldays, the YMCA, courses in salesmanship, the Bible, evangelical sermons, Shakespeare, and so on.

‘Just think of a cup slowly filling up with liquid,’ he began. ‘Then once it is full’ – here he cupped one hand and with the other skimmed off the hypothetical excess – ’it naturally flows over, and you have a wet dream.’ He paused for a bit. Then he continued, again metaphorically. ‘Have you ever seen a horse win a race without being able to maintain a steady pace? Of course not. If the horse starts out too quickly, he gets tired and fades away. The same thing with you. If you abuse yourself your cup will not run over; you can’t win or even finish the race.’ On a similar occasion later he added warnings about going bald and/or mad as a result of ‘self-abuse’, which only very rarely did he refer to as masturbation, a word pronounced with quite dreadful admonishment: ‘maaasturbation’ (the a’s almost o’s).

My father never spoke of making love, and certainly not of fucking. When I tried to bring up the question of how children were produced the answer was schematic. My mother’s frequent pregnancies, and especially her alarmingly protuberant stomach during them, never settled the question. Her line to me was always, ‘We wrote a letter to Jesus and he sent us a baby!’ What my father told me after his solemn shipboard warning about ‘self-abuse’ was a few almost dismissive words about how the man puts his ‘private parts’ in the woman’s ‘private parts’. Nothing about orgasm or ejaculation or about what ‘private parts’ were. Pleasure was never mentioned. As for kissing, he referred to it only once in all my years of being with and knowing him. ‘You must marry a woman,’ he told me when I was in college, ‘who has never been kissed before you kissed her. Like your mother.’ There was not even a mention of virginity, an abstruse concept that I had heard about in Sunday school and then through catechism and that acquired some concrete meaning for me only when I was about twenty.

After we returned from America in the autumn of 1948 there were two or perhaps three occasions when we had man-to-man talks, each time with a growing sense on my part of encroachment and guilt. I once asked him how one would know that the wet dream had occurred. ‘You would know in the morning,’ was his first answer. As with most things then, I was hesitant to ask more, but I did when he next brought it up, along with a still more embellished account of the evils of ‘self-abuse’ (the man becoming ‘useless’ and a ‘failure’ as the degeneracy took final hold). ‘A wet dream is a nocturnal emission,’ he said. The phrase sounded as if he was reading it off a page. ‘Is it like going to the bathroom?’ I asked, using the euphemism we all used for urinating (‘pee-pee’ was the definitely riskier alternative, which my mother always admonished me against: I used it when trying to be ‘naughty’, along with ‘I can see your pants!!’ to one of my sisters, as a further act of insubordination and intransigence).

‘Yes, more or less, but it’s thicker and sticks to your pyjamas,’ he said then. So this was why the pyjamas were being clinically transported in his left hand as he stood a few feet away from my bed. ‘There’s nothing on these pyjamas at all,’ he said to me with a look of scowling disgust, ‘nothing. Haven’t I told you many times about the dangers of self-abuse? What’s the matter with you?’ There was a pause, as I looked furtively past my father towards my mother. Although I knew in my heart that she sympathized with me most of the time, she rarely broke ranks with him. Now I couldn’t detect any support at all; just a shyly questioning look, as if to say: ‘Yes, Edward, what are you doing?’ plus a little bit of ‘Why do you do nasty things to hurt us?’

I was seized with such terror, guilt, shame and vulnerability that I have never forgotten this scene. The most important thing about these feelings is how they coalesced around my father, whose cold denunciation of me in my bed utterly silenced and defeated me. There was nothing to confess to that he didn’t already know. I had no excuse: the wet dreams hadn’t in fact occurred, even though for a time during the past year I did wake up anxiously, searching bed and nightclothes for evidence that they might have. I was already down the road to perdition, perhaps even baldness. (I was alarmed after a bath once to notice that my wet hair, normally quite thick, showed a couple of patches of what appeared to be baldness. I also suspected that my father’s insistence on frequent haircuts was connected to deterring the premature effects of self-abuse. ‘Have your hair cut often and short, like your father,’ he’d say, ‘and it’ll remain strong and full.’) My secret, such as it was, had been found out. All I could think of was that I had no place to go as the dreadful retribution was about to occur. For a moment I felt as if I was clinging to ‘Edward’ to save him from final extinction.

‘You have nothing to say, do you?’ A quick breath, then the climax. He threw the pyjama bottoms at me with vehemence and what I thought was exasperated disgust. ‘All right then. Have a wet dream!’ I was so taken aback by this peremptory order – could one, in fact, if one wanted, just have a wet dream? – that I shrank back even further into the bed. Then, just as I thought he was going to leave, he turned towards me again.

‘Where did you learn how to abuse yourself?’ As if by a miracle I was given an opening to save myself. I recalled in a flash that only a few weeks earlier, near the end of summer and just before school started, I had been loitering in the boys’ dressing room at the Maadi Club. Although it was at the time my father’s favourite club for golf and bridge, I knew relatively few people and, with my usual shyness, would go into the dressing room to get into my bathing suit but would also take my time, hoping to strike up a friendship perhaps, or meet a stray acquaintance. My feeling of loneliness was unallayed. This time, however, a gaggle of older boys, wet from swimming, burst in. They were led by Ehab, a very tall and thin boy with a deep voice that exuded confidence. Rich, secure, at home and in place. ‘Come on Ehab, do it,’ he was urged by the others. I had seen him before but had not really met him: our fathers did not know each other and I was still dependent on this kind of parental introduction. Ehab lowered his trunks, stood on the bench, and while peering over the wall at the pool’s designated sunbathing area, began to masturbate. I heard myself blurt out, ‘Do it on Colette,’ Colette being a voluptuous young woman in her twenties who always wore a black bathing suit and had graced my own private fantasies. No one heard me; I felt like an ass and blushed uncontrollably though no one seemed to notice. We were all watching Ehab as he rubbed his penis slowly until, at last, he ejaculated, also slowly, at which point he started to laugh smugly, displaying his sticky fingers as if he had just won a sports trophy.

‘It was at the club. Ehab did it,’ I blurted out to my father, who had no idea who Ehab was or what it was I was trying to say. I realized that he was not asking me for anything concrete: it was only a rhetorical question. Of course I was guilty. Of course he now knew it. My sins had also been exposed to my mother, who never said a word, but showed signs of scarcely comprehending horror and even bereavement.

My father did not seem particularly interested either in my explanation or in listening to my clumsy expressions of determined self-reform. He had found me out and found me wanting; he knew what harm I was doing myself, and he had judged me both weak and unreliable. That was all. He had told me about the cup and the racehorse, about baldness and madness. He had repeated the homilies perhaps eight times, so all he could do now would be to repeat them yet again or, ‘wisely’ (a word he liked to use), he could register the crime and move on, his authority and moral judgement remaining forcibly intact. I was neither punished nor even reminded of my secret vice. But I didn’t think I had escaped lightly. This particular failure of mine, embodied in that exquisitely theatrical scene, added itself, like a new and extremely undermining fault line, to the already superficially incoherent and disorganized structure of ‘Edward’.

Originally published in Granta 67, 1999

‘Self-Consciousness’, by Edward W. Said. From Out of Place by Edward Said. © 1999 by Edward W. Said. Reprinted by permission of Granta Books, by Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC., and by The Wylie Agency (UK) Ltd.

Feature artwork by Michelangelo, Male Back with Flag, c.1504

In-text photograph courtesy of the author