We live in the City of the city of London, on the edge of old Londinium, Aldersgate without, meaning ‘without’ the London Wall, a ward named for its gate, originally Ealdredesgate, circa 1000, a ‘gate associated with a man named Ealdrād’. Long empty walks, in the City of the city. Up and down Addle Street, Amen Corner, Catherine Wheel Alley, Dark House Walk, Fruiterer’s Passage, French Ordinary Court, Garlick Hill, Golden Lane, formerly Goldynglane, which gives its name, after a local property owner called Golding or Golda, to the 1950s council housing estate we live on. Round and round the Smithfield market, still humming with transport trucks, cuts and slabs of meat heaved in and out every day at the crack of dawn. Cock Lane, East and West Poultry Avenue, Milk Street, Cloth Fair, Barley Mow Passage, Cowcross Street, Rising Sun Court.

On these streets, we walk the city that no longer is, and not just because of the virus: The literal city from centuries past and palimpsest that once announced itself at each turn – bustling with market traders and craftsmen, hogs and hounds, groves of camomile and wormwood, mansions and vineyards, wharves and inns and pubs and houses of ill repute. We walk past former monasteries and convents, religious land once granted to hermetic orders then repossessed, friars beheaded, buildings in ruin, later purchased by wealthy merchants. These are now almshouses, university medical buildings, small private schools, flexible working spaces, a JP Morgan Chase, where we see bankers through slick, street-level plate glass, lounging around in large groups, playing ping pong, greasy takeout containers strewn about. When we pass they look out and laugh. B tells me not to give them the finger. But what is so funny, just now, I want to know. They think they’re inside and we’re outside, he says.

‘Poor, bare, forked animal,’ I keep hearing in my head: how Shakespeare’s Lear describes man.

Back home, every day, we walk via Postman’s Park, with its Watts Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice. This Memorial is the subject of Monument (1980–81) by Susan Hiller, who photographed the forty-one heart-rending plaques and rearranged them in the shape of a diamond.

MARY ROGERS

STEWARDESS OF THE STELLA

MAR . 30 . 1899

SELF SACRIFICE BY GIVING UP

HER LIFE BELT AND VOLUNTARILY

GOING DOWN IN THE

SINKING SHIP

SAMUEL RABBETH

MEDICAL OFFICER

OF THE ROYAL FREE HOSPITAL

WHO TRIED TO SAVE A CHILD

SUFFERING FROM DIPHTHERIA

AT THE COST OF HIS OWN LIFE

OCTOBER 26 . 1884

Bordering the west side of the park is St Bart’s Hospital, where, in 1628, William Harvey discovered the circulation of blood; where William Hogarth painted two huge staircase murals of Christ healing the sick, The Pool of Bethesda (1736) and The Good Samaritan (1737); where Holmes and Watson meet, in a chemical lab, in the novel Study in Scarlet (1887); and where – these days – people huddle nervously as masked workers rush in and out. To the east is where Elizabeth Croft, in 1554, hid in a hollow part of the London Wall just south of Aldersgate and pretended to be a heavenly messenger who disapproved of the marriage between Mary I of England and Philip II of Spain. The ethereal speech she gave allegedly gathered a supportive crowd of up to 17,000 within 24 hours – a scandal later known as ‘the bird in the wall’. To the north of the park is a stretch of street called Little Britain, which is what this island feels like most of the time now. Hiller’s Monument includes one unofficial tile, graffitied with smudged and dripping letters:

STRIVE TO

BE YOUR

OWN HERO

*

The City of the city is jagged and spiky, tangled, twisted – burned down, paved over, rebuilt, unruly with wealth and poverty side by side, as they have always been. A punished and punishing place. In the City of the city, with each cardinal boundary guarded by a gothic, cast iron dragon, I feel dwarfed and secret and ancient and a little bit powerful, on the wide, now-vacated streets. Walking through a city within a city within a city with no temporal end but the seemingly interminable present, I make my way to Fore Street, where Daniel Defoe lived in one of only two houses on the street to survive the fire of London in 1666, one year after the Great Plague of London killed an estimated 100,000 people – roughly a quarter of the City’s population. Defoe was just five years old at the time: his famous A Journal of the Plague Year (1722) is based on the journals of his uncle Henry Foe, a saddler who lived in Whitechapel. In it he – or rather his narrator, HF – writes of the plague whose cause was unknown, ‘I have heard it was the opinion of others that it might be distinguished by the party’s breathing upon a piece of glass, where, the breath condensing, there might living creatures be seen by a microscope, of strange, monstrous and frightful shapes, such as dragon, snakes, serpents, and devils, horrible to behold.’

Fear makes people see things. I am reading Defoe and I am walking the city because I cannot stop thinking about seeing things. In the winter before the Great Plague, and again, in the autumn before the Great Fire, it was said that an unusually bright star or comet was seen blazing for several months in the sky over the City. The comets passed ‘so very near the houses,’ writes Defoe, ‘that it was plain they imported something peculiar to the city alone.’ Some people follow the premonitions that appear in the dreams of old women. Some hear voices of warning. Some see apparitions in the air: A flaming sword held in a hand extending from a cloud, the point hanging directly over the City; hearses and coffins and legions of dead bodies flying through the sky; an angel in white, brandishing a glowing blade; ghosts walking among gravestones. Astrologers examine the conjunctions of the planets and observe them to be ‘in a malignant manner and with mischievous influence’. Grocers, who reluctantly continue to enter the City to sell their goods, soak coins in buckets of vinegar for hours before counting their profits. Tobacco, also, is said to have prophylactic qualities. On the outskirts of London, people who have fled the City are chased and dragged through fields, some killed in gruesome fashion: back from whence ye came – a Little Britain speciality.

Three-hundred and fifty-five years later, as we are overwhelmed with information about our modern plague, spectral anxiety and speculation take over, sanctioned and not. ‘Anxiety is altogether different from fear and similar concepts that refer to something definite,’ writes Kierkegaard in The Concept of Anxiety. ‘Anxiety is freedom’s actuality as the possibility of possibility.’ So yes, maybe it’s the 5G masts, let’s burn them to the ground. Maybe we could inject disinfectant, swallow bleach, expose the inside of the body to light. Do cocaine, drink cow urine, take coconut oil. Coronavirus is biological warfare; coronavirus came from space. The possibility of possibility. I read about the planets and of how on 31 January, 2020, the first recorded case of coronavirus in the UK, Ceres entered Aquarius; and on 31 March, Mars, Saturn, and Jupiter were in rare and close alignment, a prelude to 21 December 2020’s ‘Great Conjunction’, when Saturn and Jupiter will meet in the post-sunset skies at just 0.06 degrees apart. As I write this, on 4 May, Venus, pink mistress, can be seen in the dusk sky between the bright stars Capella and Betelgeuse, though the latter, the ‘red giant’ of Orion’s shoulder, was rumoured to be on the point of exploding late in 2019. But I know nothing about astrology or astronomy or celestial portents, so I read the Guardian, the New York Times, the Globe and Mail, the Atlantic, the Financial Times, Novara Media, The Canary, Maisonneuve, Toronto Life, Le Monde, until my eyes go fuzzy and blur.

Sylvia Plath transcribed in her journal on Tuesday, 14 October 1958, that same passage of Defoe’s about the ‘monstrous and frightful shapes’ that might be seen in the breath of the ill, following it with her own note – ‘the chaemeras of the sick mind also’. At the time, Plath lived in Boston with her husband Ted Hughes, who was teaching poetry at the University of Massachusetts. Plath audited Robert Lowell’s poetry writing workshop at Boston University while working part-time as a secretary at Massachusetts General Hospital’s adult psychiatric clinic, where she transcribed the records of patients, a process she found invigorating: ‘I feel my whole sense & understanding of people being deepened & enriched by this: as if I had my wish and opened up the souls of the people of Boston & read them deep,’ she writes in the same journal entry leading up to the Defoe quotation. ‘Fear: the main god: fear of elevators, snakes, loneliness – a poem on the faces of fear.’

And I get this: Defoe and Plath, Defoe in Plath. Fear: the main god. Fear: of being alone. Fear: of going mad and dying far from home. Although Plath liked to look hard, I think one day, walking past Smithfield market again, with its hooks and pulleys and that faint, ever-present butchery smell, which is simply the meat itself. On a BBC programme called What Made You Stay?, about foreigners living in the UK, Plath spoke of her devotion to British butcher shops: ‘I’m not by any means an expert, but I think you have to know your cuts of meat and it’s a rather creative process to choose them out of the animal almost on the hook and I think this is an experience that I – I really was deprived of in America.’

I have been emailing with WK about Plath and her vowels, so I send him this quotation, which he says reminds him of a Lowell sonnet written long after Plath’s death. ‘They were both hook-conscious,’ he replies, which is just the right way to put it. Cries and smiles and words as hooks. ‘Every little word hooked to every little word,’ Plath writes, and ‘the air is a mill of hooks.’ ‘I want words meat-hooked from the living steer,’ Lowell writes, and ‘All day the words hid rusty fish-hooks.’

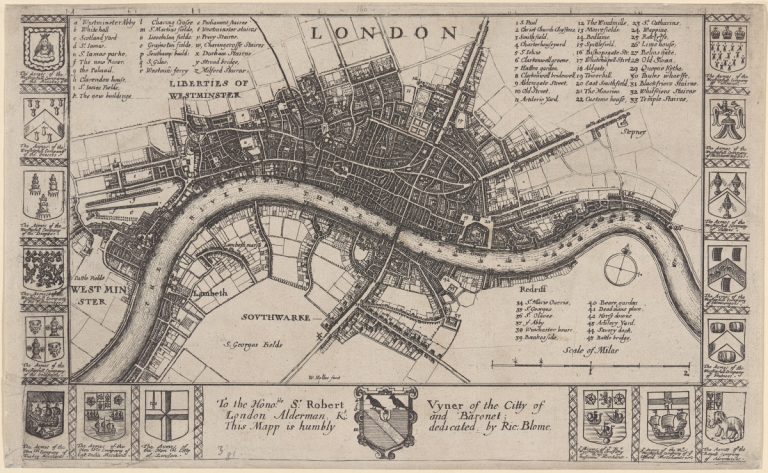

Around the corner is Charterhouse Square, which once bordered a large Carthusian monastery. The pentagonal yard covers a 1348 plague pit, the largest Black Death mass grave in London – an estimated 50,000 bodies. Since then the land has never been built on. It survives in the earth, B tells me, but I’m not sure. Wenceslaus Hollar’s circa 1665 map of London shows Smithfield market and Charterhouse Square and, if you look closely, a stone’s throw away, where we live now. If you look even closer, zoom out and squint and shake your head a little from side to side, you can also see that the map looks like an oriental rat flea – the variety that would have been infected with Yersinia pestis, which blocked its gut so that the bacterium was regurgitated into wounds of hosts when the insect attempted to feed. I do not think I am imagining this, nor the little hooks on the ends of its many arms and legs.

CFW tells me that in the park near his house they have built a temporary mortuary. OG has gone to stay with her parents Israel because she fears the loneliness of isolation London, and I don’t blame her. MR is painting big paintings, as many as she can. I am trying to write, I tell her. We can’t figure out if we should be doing something different. Like we had been waiting, but were not entirely prepared, for the thing that would all of a sudden make our lives seem as slight as we had, in our worst moments, already imagined them to be. BS says that he refuses to look at art online and would rather spend the rest of his days, as Joe Brainard did, reading Victorian novels. We all miss the fact that museums and galleries, along with all cultural institutions, are physically closed and may remain so indefinitely. This is not trivial – not just a passion, but a livelihood and an education, though all of these are equally real and vital.

‘What we seek in museums is the opposite of what we seek in churches – the consoling sense of previous visitation. In museums, rather, we seek the untouched, the never-before-discovered; and it is their final unsearchability that leads us to hope, and return,’ writes John Updike in ‘Museums and Women’. Throughout the story, Updike’s protagonist reveals himself to be a profoundly unnuanced beholder – he likens women to rooms of empty vases, and mute, transparent museums filled with possessable objects. This is a troubling view, of both women and museums, never mind what else; but what Updike gets right is that, in life as in fiction, museums and galleries act as places of exchange, proxies for our relationships – to others, to ourselves, to looking – and in them, we are never entirely alone.

I prefer the bruised and vexed looking in Jean Stafford’s short story ‘Children Are Bored on Sunday’. Stafford’s first marriage was to Lowell (to her he dedicated his second book of poetry, Lord Weary’s Castle), and she too is no stranger to hook-consciousness – though perhaps it’s more like snag-consciousness – what the hook does: snags of the heart, the mind, the memory, the eye. Emma, Stafford’s disconsolate protagonist, wanders through the Metropolitan Museum of Art, whiling away a solitary afternoon. On her way to the Botticellis, a chance glimpse of an acquaintance – Alfred Eisenburg – sets off a torrent of shame and embarrassment. Oh, she drinks too much at parties! Yes, she’s educated, but her lack of depth and sophistication make her seem stupid! She doesn’t fit in, people can tell, she is pitiable and fraudulent. She loves looking at paintings, but can only read them in personal terms that focus on evocative details: the eyes of Botticelli’s horses in Three Miracles of Saint Zenobius (c.1500); the peaches of Crivelli’s Madonna and Child (c.1480); the plump cats that lurk in Goya’s ‘Red Boy’, formally known as Manuel Osoria Manrique de Zuñiga (1787–88). She cannot appreciate Rembrandt’s Man in Oriental Costume (‘The Noble Slav’) (1632) – ‘it was this kind of thing, this fundamental apathy to most of Rembrandt, that made life in New York such hell for Emma.’ By the time she gets to the Holbeins, she can no longer see anything but her own suffering and grief. An outsider, she feels keenly ‘the physical affliction by which the poor victimized spirit sought vainly to wreck the arrogantly healthy flesh’. As luck would have it, Alfred re-appears and seems to be in a similarly tortured state: The Met will do that to you, I guess. They leave together, heading for a dark bar across town – somewhere they can be without scrutiny.

*

On my last day out in London, still a week before official UK lockdown, I went to see Alina Szapocznikow’s work at a gallery in Mayfair. The streets of the West End were disconcertingly normal, filled with tourists and frantic weekend shoppers, but I could feel a soupçon of paranoia. People veering as far away as possible in narrow passages; leaning against doors to open them with shoulders rather than hands; glancing at each other askance (can you tell just by looking?). It is almost impossible to look at Szapocznikow’s work without thinking of touch: of wanting to touch, run your hands across rough surfaces, fondle, cradle, hold sculptures against the body, throw them in the air, as the artist did, with her Envahissement de Tumeurs (Invasion of Tumours) (1970) – globes of different sizes made of crumpled newspaper, plastic, tape, resin, detritus. A man comes into the gallery and is greeted with exuberance by the assistant at the desk – how are you?! He recounts in detail his recent and grisly illness, voice echoing through the space, sniffling, sneezing. I hide in the back room, lingering too long over a series of lamps made of breasts, mouths, resin, glowing, pink, black, until he leaves.

How to preserve things so that you can see them forever? A commonplace book of images? A suite, like Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition (1874) – eleven pieces, plus a recurring ‘Promenade’, written for piano and in homage to the composer’s friend the artist Viktor Hartmann, who had died suddenly of an aneurysm the year before. Each of the eleven main pieces corresponds to a work in a memorial exhibition organised for Hartmann, with five ‘Promenades’ interspersed at different intervals. Some walks are lengthier than others – a long hallway, maybe? A turn outside on the terrace, a pause to rest on a bench, chat with a fellow visitor? Lost in thought, perhaps: the longest walk of all. In spite of being in posthumous memoriam, the suite as a whole is cheerful, major key signatures; though it takes a dark and minor turn at picture 8, ‘Catacombae’, whose score Mussorgsky had annotated: cum mortis in lingua morta – with the dead in a dead language.

SEARCH FOR: “plague,” “government,” “governors,” “magistrates,” “aldermen,” “ministers,” “politics,” “hospital,” “doctor,” “mortality,” “sick,” “poor,” “wealthy,” “fear,” “anxiety,” “quarantine,” “red cross,” “bodies,” “pits,” “dead,” “language,” in:

Thucydides, The History of the Peloponnesian War (431 BCE)

Giovanni Boccaccio, The Decameron: Prince Galehaut (1353)

Sameul Pepys, The Diary of Sameul Pepys (1666–1669)

Nathaniel Hodges, Loimologia, or, An Historical Account of the Plague in London in 1665: With precautionary Directions against the like Contagion. By Nath. Hodges M.D., And Fellow of the College of Physicians, who resided in the City all that Time (1721)

Daniel Defoe, Journal of the Plague: Being Observations of Memorials, Of the Most Remarkable Occurences, As well Publick as Private, Which Happened in London During the last Great Visitation In 1665. Written by a Citizen who continued all the while London (1722)

Albert Camus, The Plague (1947).

Do not know what I am looking for, exactly, but find two things of note:

According to Defoe, some wrote the word Abracadabra on their doors, “formed in a triangle or pyramid, thus:—”

ABRACADABRA

ABRACADABR

ABRACADAB

ABRACADA

ABRACAD

ABRACA

ABRAC

ABRA

ABR

AB

A

And,

In 1665, Westminster was an independent town with its own liberties, joined to London by urban development; and it was here that the plague first raged ‘in its extreamest violence’, before spreading into and across the City of London.

In Arcades Project, Walter Benjamin writes, ‘Que les choses continuent comme avant: voilà la catastrophe.’ But they do; things do continue as before.

Boundaries begin to dissolve. A terrible feeling of:

GOING DOWN IN THE

SINKING SHIP

The scientists now say that ‘Oumuamua, the cigar shaped astral object, was labelled ‘a comet in disguise’. It is actually an ‘active asteroid’ that was ‘formed from a body that was torn apart by its parent star and then ejected into interstellar space’. As it turns out, there are many of these bodies, which can experience a number of different forces as they pass their star.

Strange to read of a country besieged when everywhere feels empty. The war against coronavirus, the virus attacks, comes in waves like flanks, an ambush, it is a battle, the war cabinet meets again this week, we must wrestle it to the ground, we will defeat it. This is the cacophonous, embodied language of the state, which has a particular purpose and effect. So here we are, back at fear, or worse, dare I say it, murder, because if you are responsible, that’s what negligence is. In The Body in Pain, Elaine Scarry writes of the ways in which physical pain is subject to verbal strategies. In the language of patients, physicians, amnesty workers, lawyers, artists, these strategies ‘revolve around the verbal sign of the weapon’, which confers a degree of autonomy upon the sufferer. But in the mouths of officials, this verbal sign can be coopted to inflict rather than to assist in the reduction of pain – invoked to make it less, not more, visible. This is what I think every Thursday night when we clap from our balcony, bang on pots, cheer, wave to neighbours. Huzzah! The NHS isn’t a charity!!! A happy cacophony to cover over what it must sound like in wards full of ventilators; a palliative rhythm to drown out the videos of nurses crying because they are working twenty-hour shifts and by the time they get to the shops, the food is gone; the voices of frontline workers who have died; the mourning of families who cannot attend the funerals of loved ones. This is what I think when I remember the empty shelves for weeks, people running from the stores with huge sacks of toilet paper and all the paracetamol; or that triumphant moment of finding one fennel bulb and a tiny ham hock at the back of a ledge, because the aisles were stripped. This is not normally the city I think I live in, but it is of course always the city I live in. And what is the language for this place?

ABRACADABRA

ABRACADABR

ABRACADAB

ABRACADA

‘The hospital dusted wounds with powders the worth of which was not quite established, other supplies having been exhausted early in the first day,’ writes Donald Barthelme in ‘The Indian Uprising’, a story about a city actually besieged, even as the reasons for conflict remain unclear (and ultimately allegorical). ‘I decided I knew nothing,’ the nameless narrator says, looking at the wreckage around him. ‘People were trying to understand. I spoke to Sylvia. “Do you think this is a good life?” The table held apples, books, long-playing records. She looked up. “No.”’ In London, the sun is blazing for days; the birds are growing wild and proliferate; plants sprout up everywhere, unusually tall and from the tiniest of cracks; for the first time I can sleep through the night, no endless orange hum of traffic, no planes flying low overhead. I am too ashamed to complain about anything because I am healthy and have a safe home, which should be an inalienable right, but is not. Do you think this is a good life? I want to ask B, but don’t.

If there is a new language for this place, however mobile and ad hoc, it is one of proximities and distances, with their radically redefined values and daily allowances, shifting, ever shifting. Or perhaps the new language would be one of philosophy and inversions and refusal, like that of Wittgenstein, who wrote in Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, ‘Anybody who understands what I’m saying eventually recognizes that it’s nonsense, once he’s used what I’m saying – rather like steps – to climb up past what I’m saying – he must, that is, throw away the ladder after he’s used it.’

In David Markson’s Wittgenstein’s Mistress, the titular philosopher’s Tractatus – which investigates the relationship between language and reality – takes life in the embodiment of a woman named Kate. Seemingly the last person on earth, Kate wanders empty streets, recording her movements, thoughts and memories as they unfold in spare, telegraphic statements, unmoored in time and space. Kate is truly in isolation, a fact that calls into questions all previous givens. For what is this body, then? For what these national borders, this history? For what these books and paintings? And how to determine, alone, always alone, what is reality, what its constitutive principles? As it was for Wittgenstein, ‘Cogito, ergo sum’ doesn’t hold quite enough water – more evidence is required. Throughout the novel, Kate speaks extensively of paintings, artists, galleries. She has lived in the Louvre, the National Gallery, the Metropolitan Museum, the Tate Gallery, the Rijksmuseum, the Prado, each time leaving messages in the street as to her whereabouts, but no one ever comes. She knows her Giotto, her Rogier van der Weyden, her Piero di Cosimo, her Piero della Francesca, Hugo van der Goes, Rembrandt van Rijn, Joseph William Mallord Turner, Vincent van Gogh. Sunsets and sunrises each day are described by the palettes of specific artists, although she admits that she has to dismantle the frames of many a famous work to burn for warmth. Like Stafford’s Emma, Kate is never quite sure what it is supposed to be about Rembrandt, until she sees The Nightwatch in person – ‘it sent shivers up and down my spine . . . As if there were a glow from inside of the pigments themselves practically . . . To this day I have never quite been able to solve how Rembrandt managed to bring that off, either. Well, which is why he was Rembrandt, presumably.’

Is this Markson’s flirtation with Wittgenstein’s “picture theory of language”? The function of language, the Tractatus tells us, is to allow us to picture things, sometimes literally to draw them – as in a diagram or a representation. What a picture means is independent from its truthfulness, because all pictures live in what Wittgenstein calls ‘logical space’ – which means that a picture need not have happened or be real, because a picture is a possible situation. Sentences work like pictures: their purpose is also to picture possible situations. By this token, writing and art do the same: here, a world in which you might live; here, a world in which you already do. By this token, we really need to see things: we need to see things all of the time. I’m sure I’ve made a meal of this, but one thing I can tell you for sure is that it is possible to watch The Nightwatch being restored, no matter where you are. Or at least it used to be. The livestream of Operation Nightwatch (so named because, the Rijksmuseum says, it is “like a military operation”) has been paused for the foreseeable future.

*

On the day that I go to find the pure gold baby, as I have been calling him, after Plath’s ‘Lady Lazarus’ (‘I turn and burn / do not think I underestimate your great concern’), the sun is again blazing, the sky a near unholy cerulean blue. Up to the corner of Ray Street Bridge and Herbal Hill, once Hockley-in-the-Hole, a pit where bears and hounds and other animals, including men, were pitted against each other, and where – if you walk into the middle of the road and put your ear to the ground on a quiet day, which is now every day – you can hear the Fleet River still running beneath. Down past Farringdon station, the terminus of the original Metropolitan Railway, the world’s first underground metro line. Down and down again to the Golden Boy of Pye Corner, a chubby little fellow made of wood. Gold-painted and formerly winged, he stands on an S-shaped moulding, arms stubbornly crossed over his chest, looking into the far-right distance.

This Boy is

in Memmory Put up

for the late FIRE of

LONDON

Occasion’d by the

Sin of Gluttony

1666

it says below, and below again, a note about how the fire started at Pudding Lane (‘Pudding’ meaning entrails, this was where they threw them), and ended here at this corner of Giltspur Street and Cock Lane. ‘The boy was made prodigiously fat,’ it continues, ‘to enforce the moral,’ and originally built into the face of a public house called The Fortune of War. This pub, with its convenient location near a hospital, was also ‘the chief house of call north of the river for resurrectionists in body snatching’: the landlord collected bodies and placed them round the walls, ‘labelled with the snatchers’ names, waiting till the surgeons at St Bartholomew’s could run round and appraise them.’

I take photographs of everything, but they are shitty and blurred, like the lens is covered in grease. Maybe it’s the sun, but it might also be grief. That morning I had read of Portapique and the rampage of murders – now the deadliest mass killing in Canada, exceeding the Montreal Polytéchnique massacre of 1989. I am not from Nova Scotia, but Ontario – nonetheless I feel far from home. Portapique is a town of one-hundred people, fewer in the winter, which means that twenty-two dead is probably at least a quarter of its population. It was Portapique that inspired Elizabeth Bishop to write ‘At the Fishhouses’, in which she describes the sea that swings ‘icily free above the stone’. This is water so cold, she writes, that if you dipped your hand in, it would burn and ache; and if you tasted it, it would be bitter and briny and burn your tongue, too.

It is like what we imagine knowledge to be:

dark, salt, clear, moving, utterly free,

drawn from the cold hard mouth

of the world, derived from the rocky breasts

forever, flowing and drawn, and since

our knowledge is historical, flowing, and flown.

Bishop also wrote, ‘I lost two cities, lovely ones. And vaster, / some realms I owned, two rivers, a continent,’ and of course that ‘the art of losing’s not hard to master / though it may look like (Write it!) like disaster.’ I have always loved that riddling italicised parenthetical, with ‘like’ buttressed either side, as if Bishop had to remind (trick? goad?) herself into remembering that what goes onto the page transforms if not heals the losses of daily life into something useful: art, an art.

I don’t want to die on this island, I told CD last year, in a maudlin moment. Her eyes widened, but it’s true, I don’t.

‘In a certain way, works of art would make fools of us were it not that their fascination is proof – unverifiable though undeniable that this paralysis of the intelligence combines with the most luminous certainty. What that certainty is, I do not know,’ writes Jean Genet in his strange and apothegmatic text, What Remains of a Rembrandt Torn into Four Equal Pieces and Flushed Down the Toilet. Genet writes of Rembrandt’s paintings as works that stun and transfix, because they strive for the depersonalised and so universal – ‘when he prunes objects of all identifiable characteristics . . . he gives them the most weight, the greatest reality.’ It matters not if Rembrandt’s subject is a person or an object, Genet notes, because all particulars dissolve and merge with the viewer who embraces the fleshy, embodied looking the painter’s work gives and in turn demands – before and within a Rembrandt, we are all equal.

In ‘Bathsheba, or the interior Bible’, Hélène Cixous writes of this same involved and corporeal looking in words even more spare and torn, aleatory, wayward. ‘The Rembrandt(‘s) sex is matrical,’ she proclaims at the outset, before taking us through Rembrandt’s Bathsheba at Her Bath (or Bathsheba with King David’s Letter) (1654), and then through and down and down, into his Slaughtered Ox (1655), also known as Flayed Ox, Side of Beef, or Carcass of Beef. For Cixous, the power of Rembrandt is that he paints what we cannot see: the moment in which Bathsheba’s solitude is pierced by a call to King David’s bed; the solitude of the slaughtered Ox, hung upside down by its legs, as our human mortality; how when we want to forget death ‘we cut the dead one up into pieces and we call it meat’. Poor, bare, forked animal.

*

The earliest example of ‘weepers’ (or ‘pleurants’, the tiny mourning figures that decorate tomb monuments) in England are on the 1293 tomb of Joan de Vere in Chichester Cathedral, which also houses rare reliefs, from the same century, of the Raising of Lazarus. In one, Mary and Martha, who have gone to meet Jesus, are in the upper left background, clutching their stone faces in frozen grief as two tiny figures below prize open the ground for Lazarus to rise and rise. With the dead in a dead language. During the Great Plague of London (as well as before and after), women were enlisted to be ‘searchers of the dead’. Often elderly, uneducated and poor, these women were tasked with going around the City to examine corpses, determine the cause of death, and report their findings to the Parish Clerk House for the official bills of mortality. Sometimes the women were bribed to report incorrect findings so that those family members who survived would not have to be ‘shut up’ (doors nailed closed, windows boarded over, painted with red crosses); sometimes the women had to live far outside of common areas and to carry white sticks with them wherever they went; frequently they died violent deaths from the diseases they were required to diagnose. I cannot find precise evidence of the 1665 site of The Worshipful Company of Parish Clerks, but to my best knowledge it is just about where now stands the London Chamber of Commerce and Industry, ‘the capital’s largest independent networking and business support organisation’.

In the iconoclastic wars of the sixteenth century, it was a common barb to accuse something of being a ‘dead image’, to say that those who invest their hope in images ‘do not have a living faith but a dead one’. Well give me a dead faith any day, in that case, because I believe in the writing, ekphrasis, criticism, exegesis of images: not that these cause images to reply to us, as in prosopopoeia, or to meet our demands (for we often have many, where art is concerned), but these processes reveal something we did not already know, lead us to experiences otherwise unreachable. In ‘Archaic Torso of Apollo’, Rainer Maria Rilke writes of how the titular object, though missing its legendary head, ‘is still suffused with brilliance from inside, / like a lamp, in which his gaze, now turned to low, / gleams in all its power.’ The proof of this power is that the object is able to dazzle, glisten, transfix, and from ‘all the borders of itself, / burst like a star.’ By the end of the poem, its writer has come so close to the work of art that it addresses him (and his reader): ‘You must change your life.’ The headless fragment and the poem alike tell us that a work of art is not merely a reproduction or a representation of reality, but an enrichment, an expansion that is itself deeply human and personal.

In The Sight of Death: An Experiment in Art Writing, T.J. Clark’s intense and often intimate book that spans three years of close-looking at two paintings by Nicolas Poussin, he quotes the painter in correspondence with one of his great patrons, Paul Fréart de Chantelou. ‘Il vaudra mieux que je m’estudie aux choses plus aparentes que les paroles,’ Poussin wrote, ‘Better for me to apply myself to things more apparent than words’. Poussin also referred to his paintings as ‘Mes tacites images’ and described himself as a painter, ‘Moy qui fais professions des choses muettes’. Clark’s project is in many ways to try to fill this void of muteness – to use language to investigate just why and how we are held in place by some images, spellbound and haunted, even as we remain at a luminous distance. ‘Paul Valéry says somewhere that a work of art is defined by the fact that it does not exhaust itself – offer up what it has to offer – on first or second or subsequent reading,’ Clark writes. Images do not happen all at once, they repeat themselves, they bear repeating; and it is the duty of writing to imitate or address that state of suspension or dispersal that looking at art can be. Writing, Clark says,

should not flinch from making sense of the mute things it is looking at (making sense of mute things is a normal activity of language, and any patter about the special un-translatability of paintings misses that obvious point), but it should invent ways for this explicitness to be overtaken again by the thing-ness, the muteness, of what it started from.

How far does our duty to looking and to describing extend? Clark’s mission is specific, and stems originally from his proximity to the two Poussin paintings in question: Landscape with a Man Killed by a Snake (1648), and Landscape with a Calm (1650–51). During the course of looking, however, the paintings and their import begin to spread further and further. Clark’s insights reach an apex when he realises (or finally admits) that in the earlier painting, in the gaunt and pale face of the panicked washerwoman who extends her arms in alarm, he sees echoes of his mother and her death, her dead body. This is a painful punctum – amid digressions on colour and style, lighting and pentimento – but it is necessary for Clark, as well as his reader, and any would-be writer of art, not just personally but politically – a ‘coming-to-terms’ with the moment in which we live, filled with conflict, pain and death, in order to see a different possible future: ‘Affliction and monstrosity, we have to relearn, are always the true face of utopia – the face it presents as it leaps up out of the immoveable, out of the insufferable everyday.’

‘People don’t become inured to what they are shown . . . because of the quantity of images dumped on them,’ writes Susan Sontag in Regarding the Pain of Others. ‘It is passivity that dulls the feeling. The states described as apathy, moral or emotional anaesthesia, are full of feelings; the feelings are rage and frustration.’ Sontag is describing images of war, specifically photographs, though the book also draws on pre-photography images like Goya’s 1810–20 series, The Disasters of War. Why keep looking? And for how long? How many images of pain are sufficient? What could be horrible enough to evoke the commensurate amount of pity or empathy, rage or frustration, and do these emotions achieve anything substantial if they remain feelings alone, unattached to action and consequence? Pity is diluted by fear, dread, terror, Sontag writes – particularly when things are close to home, a situation none of us can avoid in a global pandemic. And yet, none of us can avoid the fact that we are not all affected equally. Jacqueline Rose writes powerfully of this in her recent essay about Albert Camus’s The Plague, whose protagonist Jean Tarrou comes to realise that in a state in which some prosper while (or because) others suffer, we each have the plague within us, and the plague is everywhere without, particularly in what the state enacts in our names. ‘The plague will continue to crawl out of the woodwork,’ Rose writes, ‘out of bedrooms, cellars, trunks, handkerchiefs and old papers – as long as human subjects do not question the cruelty and injustice of their social arrangements.’

What does this pandemic look like? How do we regard the pain of its others? In graphs of global, national, local infection rates? Charts of deaths per day, week, month? Diagrams of what the virus does to your lungs? Figures spray-painted on the ground to show two metres? Portrait photographs of those who have died? Empty shelves, empty streets, discarded masks and gloves? The New York Times front page with its 100,000 names of the dead? Meat trucks, filled with bodies, queuing to get out of NY? The laughing, smirking faces of our elected representatives? Excuse me as I sit and burn with rage, smoulder like a pyre. I read of people dying, some of them alone, some of them children, gasping for breath, and think of Scarry’s cautioning around the language of pain, and how its official grammar and syntax so often distorts and distances. ‘Vaguely alarming yet unreal,’ she writes, ‘laden with consequence yet evaporating before the mind because not available to sensory confirmation, unseeable classes of objects such as subterranean plates, Seyfert galaxies, and the pains occurring in other people’s bodies flicker before the mind, then disappear.’

I cannot imagine an appropriately ‘challenging kind of beauty’ (as Sontag describes it, the terribilità of images that appall) – a deficiency, perhaps, though I am not an artist, and I would never deny the importance of looking, of refusing to turn away. One of Scarry’s touchstones in a book that is not about pain but beauty, On Beauty and Being Just, is Simone Weil. Weil’s accounts of beauty are always somatic, Scarry writes, ‘what happens, happens to our bodies,’ just as Wittgenstein registered experiences of beauty in his teeth and gums: ‘a visual event may reproduce itself in the realm of touch,’ the effect of which is a radical decentering. According to Weil, according to Scarry, beauty requires us ‘to give up our imaginary position as the center’. To envisage a future, perhaps, in which beauty – challenging, sublime, somatic – is equally distributed, along with everything else.

In the City of the city of London, I keep walking, I keep my head up, because I know that we need to see things. Even – especially – when we are most acutely aware that we cannot.

Image © plochingen