In May 2015, Alexandra Lucas Coelho followed a team of archaeologists into northern Iraq, as they attempted to salvage Mesopotamian artefacts close to the front line with the ‘Islamic State’ (ISIS). This expedition took place in the beginning of the ISIS offensive in the ancient ruins of Palmyra, a UNESCO World Heritage site in Syria, which culminated with the destruction of its millennia-old monuments and the capture and beheading of the chief archaeologist on site.

Commander Ato leans against the sandbags and points to the horizon, an ochre line under a blue sky cut through with a column of smoke: ‘That’s the Islamic State over there.’ How far away? ‘One point eight kilometres,’ he replies, with military precision. ‘But in August they were right here.’

Here is a trench in northern Iraq, a speck on the lengthy front line that divides Kurdish troops and ISIS jihadists. There are countless signs that jihadists reached here in August 2014: behind us, the nearest village, Hassan al-Sham, is deserted, abandoned, possibly mined; the wreckage of the bridge they blew up lies spilling into the river. The Kurdish soldiers, known as peshmergas, had to build a new bridge to reach the trenches. And these are real trenches: lookouts, tents for the change of shift, barricades made of metal, wood and piled up sandbags, gaps to poke guns through and take aim.

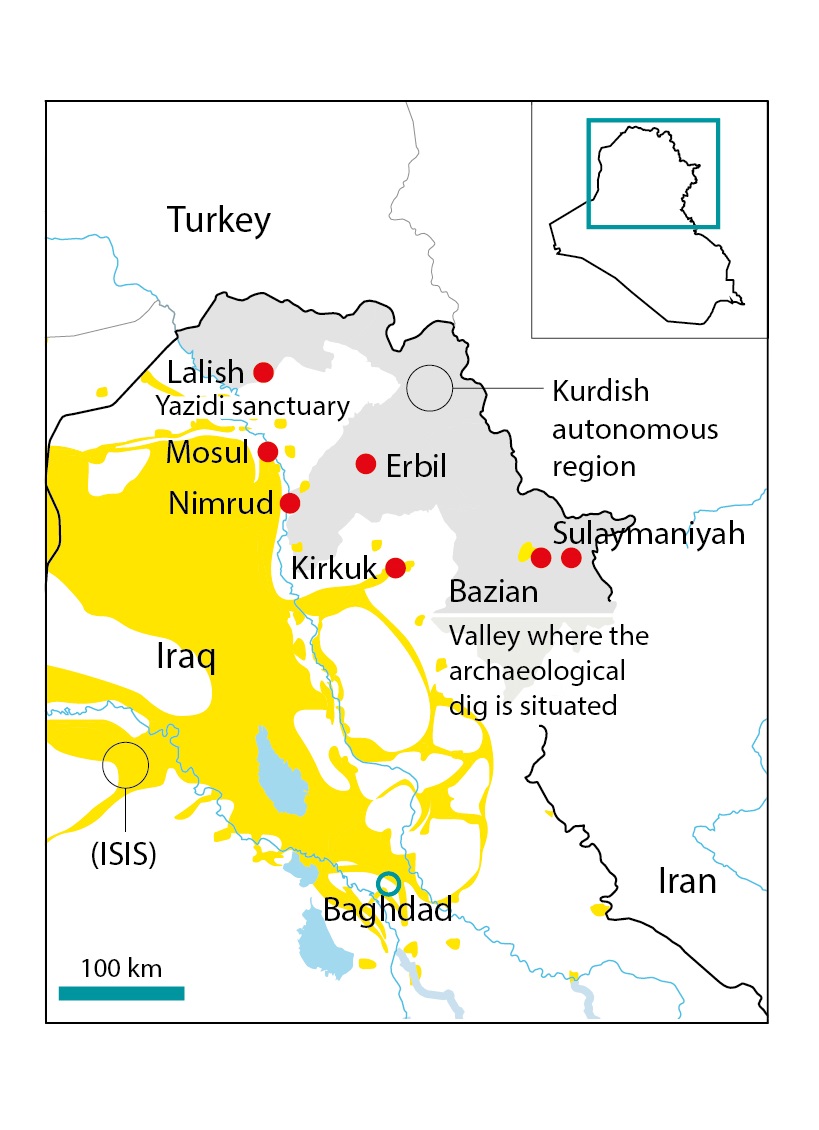

We are somewhere in between Erbil, the Kurdish capital, and Mosul, the largest Iraqi city under jihadi control. Not quite in the middle, for Mosul is nearer. If we were to walk in a straight line, we’d reach the ruins of Nimrud, the ancient Assyrian city ISIS blew up like the bridge, only with more explosives: camera, action, trailer, sequel. It happened also in Mosul and Hatra, and is now feared to be happening in Palmyra.

To maintain the fiction of the so-called Caliphate, which is not so much imperialist as apocalyptic, it is not enough to crush everything in front of you – ‘conquer Rome and rule the world’, as the self-appointed Caliph Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi proclaimed. You have to crush everything behind you too; destroy history running from the twenty-first century back to the birth of Islam, and all history before that, until there’s no history left; wipe out faces, bodies, symbols, temples, the beginning of writing, trade, cities.

All this began in Mesopotamia, the land between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers that corresponds to modern day Syria and Iraq, about which we have mere fragments of information, snippets garnered from what little was left standing or has been excavated. Further knowledge would have required more digging to be done, wars to be suspended, especially in the second half of the twentieth century. And to the current Kurdish administration, autonomous if in a constant arm-wrestle with Baghdad, it is strategically important to bring history to the surface, map it out.

One of the things you learn from standing on the top of a hill in former Mesopotamia is that archaeology makes giant strides through small cuts: tiny incisions in the landscape allow archaeologists to descend inch by inch, millennium by millennium, until they finally catch sight of a world.

That’s what five Portuguese, a Belgian, an Italian and two Kurds are doing in mid-May on a hill outside Sulaymaniyah, Kurdistan’s second city. When I left them to spend a few days at the front line, they were methodically going through all the logistics that an excavation in this part of the world entails. They’re becoming familiar with it: they were here on a dig in 2013 – before the advent of ISIS – when they uncovered a small, five-thousand-year-old clay tablet that tells of the beginning of economics; evidence of trade between the north and south of Mesopotamia. It is not a piece of the epic of Gilgamesh, which would represent the beginning of literature, but finding one is also not impossible. I will come to see this over the course of a stay in the company of refugees, soldiers, checkpoints, skulls, pottery sherds, saucepans of tuna pasta, more days without water than with and the constant reminder that Benfica, the football club, were founded in 1904, thanks to a scarf hanging in the pantry and another draped over the fridge, all part of the luggage the archaeologists brought as they returned to a part of Iraq now just a whisker away from ISIS.

*

An archaeologist’s luggage is always problematic. Almost a hundred years ago, when accompanying her husband Max Mallowan on excavations, Agatha Christie would have to sit on top of their suitcases in order to force them shut. It’s appropriate that we think of Mr and Mrs Mallowan while waiting at Lisbon airport ready to fly to Sulaymaniyah via Istanbul. Max Mallowan is a legendary figure for any archaeologist interested in Mesopotamia, no matter the political and scientific distance that separates him from Ricardo Cabral, one of the three project managers on this dig. Ricardo has read Mallowan’s memoirs and he will be sharing anecdotes throughout our journey with the other two archeologists on the team, Ana Margarida Vaz and João Barreira. Their cabin luggage piles up in the departure lounge like the belongings of a stonemason-cum-Boy-Scout-cum-technology-freak. Indeed, the modern day archaeologist is a cross between a construction worker and a drone pilot – I realize this is just the beginning.

‘It’s a good job André has already taken the total station,’ says Ricardo, contemplating the pile. A total station is a heavy surveying instrument that can neither go in the hold, because it’s too delicate, nor in the cabin, because it’s too large. André Tomé, the other Portuguese project manager, convinced the pilot to carry it in the cockpit a few days ago. He went out early to do some prep work in Sulaymaniyah, finding a house for the team to live in for a start: the one they used for the 2013 dig is in an isolated part of the valley that, since the rise of ISIS, is no longer deemed safe by the Kurdish authorities.

A few hours later, the jam-packed flight from Istanbul flies through northern Iraq, passing over Mosul, before descending to Sulaymaniyah, a brightly lit series of lines. Kurdistan has grown since the US invasion in 2003, outwards and upwards, its construction driven by local industry: oil and cement. Two modern coaches ferry passengers to a terminal where all six passport booths are open despite it being the middle of the night. The flags on display are of Kurdistan and all we require is an entry stamp; there’s no need for an Iraqi visa. Only those staying for longer than fifteen days face further bureaucracy, which is also all specifically Kurdish. It feels like entering one country inside another, a feeling that will grow over the coming days in every sense. Kurdish autonomy is a reality, Kurdistan being one of the sections Iraq is broken up into. But so long as there are still hurdles to Kurdistan becoming a country – Turkey, for example, where around a quarter of the population is Kurdish – there will still be hostility between this fragmented part and the others, Shia on one side, Sunni on the other. These fratricidal tensions exploded during the American occupation and contributed to the emergence of ISIS.

Mosul, the Iraqi ‘capital’ of the jihadists, is only eighty kilometres away from Erbil, the Kurdish capital. ISIS militants only retreated from Erbil’s surroundings after Obama ordered air strikes in August 2014. Yet they still managed to detonate a car bomb outside the American consulate, and that was in mid-April.

Our passports are stamped in the early hours of 7 May. Passengers and suitcases are then squashed up to the ceiling in a minibus left over from the Saddam era; you have to board the minibus for you’re not allowed to approach the arrivals checkpoint on foot. Kurdistan spends its time flicking back and forth like this, wanting to be Dubai but still being Iraq.

André is waiting for us on the other side. We squeeze into two cars and set off into the dead of night, bound for the village where eventually, after negotiating his way through a series of obstacles, André was able to rent a house. One of the more sensitive issues for the neighbours was that the project team would be mixed, men and women. Besides being construction workers and scientists, archaeologists have to be diplomats too, which means that rather than renting one big house, André had to secure two, the men sleeping upstairs, the women in the downstairs flat. But as there is practically nothing inside at the moment, André having only had time to fetch a few mattresses from the old house and give the downstairs flat a sweep, everyone will bunk in together tonight, on the ground floor. As for everything else, the shower has yet to be installed, likewise the cistern, so the toilet is a squatter, but to compensate the sink has a flowery decoration.

Tomorrow – which is fast approaching – a house for ten people to sleep, cook, eat and work in will have to be assembled. Spades will need to be bought, pickaxes, pitch forks, ropes, stakes, wheelbarrows, a strimmer to cut down the weeds on the hill, second-hand crockery, plastic tables and chairs, boxes to store thousands of potsherds, bags to store hundreds of human bones, labels, pens, brushes, kilos of rice, tins of food, bottles of water, because you can’t drink the water out of the tap, that is when any comes out of it, and the cooker and fridge will have to be brought from the house they used in 2013, no matter the state they’re in, because on a dig like this every penny counts.

*

While they get on with preparing the house, I take a couple of days to reach the front line.

The aim is to get as close to Mosul as possible and that means first going to Erbil. Two roads lead there, one that goes past Kirkuk (a city that was controlled by Baghdad, but that the Kurds ended up taking in the thick of the fighting with ISIS and another that goes through the mountains, along the border with Iran. We’ll take the Kirkuk road there and the mountain road on the way back. I hired a friend of a friend – let’s call him Adan – as translator and his brother will be our driver.

Green hills, cement factories, good roads, one side left over from the Saddam era, the other a product of Kurdish autonomy. Adan talks about his fear of car bombs and his compassion for the never-ending stream of refugees, hundreds of thousands fleeing areas taken by the jihadists in Iraq and Syria. Flocks of sheep coexist with gas factories. We’ve already encountered two checkpoints since leaving the house, peshmergas waving us through both times. A car with Kurdish plates occupied by people who speak Kurdish has a good chance of not being stopped. Adan explains that ‘peshmerga’ means ‘ready to die’. The Kurds are always honouring their peshmergas, and anything else remotely Kurdish in fact.

Kirkuk is an area rich in oil. We pass the oldest oil field in Iraq and, as the checkpoints multiply and we are stopped and searched, it becomes clear the fighting is now less that seventy kilometres away.

Veering north, we drive smoothly as far as Erbil, which seems calm beneath its citadel. The aisles in the market for changing money are deserted but stacked with packets of banknotes, because one dollar is worth almost 1,200 dinars. More commotion in the fruit aisles, medlars, peaches, strawberries; less at the tailors; nobody at the handicrafts. ‘Business has halved since this time last year,’ says Ali, the young vendor. Coming here to buy traditional handmade shoes, for example, is no longer much of a priority. Nevertheless, Ali has never thought of leaving. ‘We have to show pride in our ground. Those who want our blood, they’re the ones who should be afraid. If I’m needed, I’m ready to fight.’

Somewhat under renovation, and covered in Kurdish flags, the citadel feels like one of those historical monuments that’s slightly overplayed, a modest piece of heritage compared to others elsewhere in Iraq, and especially in Syria. But the view from the citadel takes in the entire horizon beyond Erbil, a flat city tucked up against the desert.

It’s Thursday, which in these parts means the pre-weekend, not a great time to be headed for the Ministry of Peshmerga Affairs, traipsing from one building to the next seeking authorisation to go to the front line. After countless phone calls, which take up the entire day, a friend of a friend gives Adan the contact of a commander who agrees to receive us.

*

We leave Erbil in the early morning and head towards Mosul, a landscape of refineries, flames and chimneys. The traffic disappears. Adan, who is co-navigating, finds a quicker route than the one the commander suggested and after taking it we come across a major checkpoint where the peshmergas pull us over somewhat bemused. Adan states the commander’s name and tries to call him on his mobile, but there’s no answer. The peshmergas say that between here and the front you have to drive quickly because ISIS is only ten kilometres away, on the other side of the river; there is a risk of snipers and the only vehicles to have passed through here so far have been military cars and those of villagers who live a little further on. The time we spend waiting at the checkpoint confirms this: a farmer’s truck here and there and an assortment of military vehicles. When the commander finally answers his phone he says we’ve taken the wrong road, but as we’re here now, it makes more sense to meet another commander at a different post. We pull away with the name of the new commander, but no clear idea of how to find him. We get lost, we turn back, we pass rivers, the road becomes deserted again, and then suddenly there’s a checkpoint leading to the military camp we’re looking for. The commander in question is not there, but his deputy greets us.

‘You’re lucky because it’s Friday, we’ve got a bit of time,’ says Commander Ato Zibary, inviting us into his office. In pride of place is a photo of the Kurdish president, Masoud Barzani, who met Obama in Washington only the previous Sunday. It’s an organised camp, armoured cars lined up outside, peshmerga soldiers standing to attention, well-furnished offices.

Zibary is a ‘political’ peshmerga, one appointed by the presidency. At his side is General Dedawan. Their battalion controls a thirty-five kilometre strip of the front line outside Mosul. Can the commander explain how, in June 2014, such a large city could fall to a thousand or so jihadists against thirty thousand Iraqi soldiers, and in just four days? ‘Mistakes made in Baghdad,’ replies Zibrary. ‘The sectarian divide between Shia Arabs [in the Baghdad government] and Sunnis made it possible. They regret it now that they realise they can’t fight on their own. This divide has nothing to do with the Kurds, we are Sunnis, but we also have Yazidis and Christians, everyone living together.’ The commander goes on to say that if Iraqi troops come with Shia militias to retake Mosul, the Kurds will not participate: ‘Because we know the militias will kill a lot of [Sunni] civilians in Mosul.’ However, until the retaking of Mosul gets the green light, the peshmergas will stand their ground. ‘We get a lot of help from the American air force, from Germans, Canadians, Italians, French . . . They take twelve to fifteen minutes to get here from Kuwait.’

Retaking Mosul is a ‘political decision,’ according to Zibary. ‘It depends on when the Iraqi army is ready, because we’ve been ready for ages. More than ready, for if it weren’t for us, ISIS would have conquered Baghdad by now.’

Herein lies the tension of this military amalgam: Sunni Kurds, disgruntled Arab Sunnis, Shias supported by Iran, Obama’s air force and allies; a cauldron of enemies that now have a common goal, bringing down ISIS whereas two years ago, in some cases, they contributed to its rising by arming Syrian jihadist rebels against Assad. Two years ago, nothing was worse than Assad; now nothing is worse than ISIS, this Frankenstein’s monster generated by civil wars on two sides of a border that no longer exists: the border that divides Syria and Iraq. If the war in Syria was against Assad and the war in Iraq pitted Sunnis against Shias, today there is a ‘state’ larger than Great Britain wedged in between the two countries, with a capital on either side of the supposed border (Raqqa in Syria, Mosul in Iraq) and everything shattered around it. As a product of all the foreign interventions and counter-interventions waged since 2003, from the USA to Russia, Saudi Arabia and Iran, it’s difficult to imagine a worse possible outcome.

Zibary, a 50-year old Kurdish commander who fought against Saddam, sees ISIS as ‘a continuation of al-Qaeda, strengthened by Baghdad mistakes’ made since 2003. ‘America overthrew Saddam and gave power to the Shias, benefitting Iran. The result of the American invasion was to deliver Iraq to Iran. All these mistakes led to ISIS.’

General Dedawan adds: ‘ISIS combines experience from the war in Afghanistan, Chechnya, Saddam’s regime, the Syrian civil war and Western interventions. They are the strongest enemy known to man.’ Then looking me right in the eye, he says: ‘If they defeat the peshmergas, you won’t feel safe in Portugal. We’re fighting for you too.’

*

The commander agrees to show us the trenches. In a matter of minutes, three armoured cars fill with men, including a marksman, and we head off along a deserted road, through considerable wreckage, passing Hassan al-Sham, now a ghost town, and the bridge the jihadists blew up.

Around eight-hundred peshmergas are active in this region, rotating on ten day tours of duty. Smoke fills the air coming from the scrub soldiers burn to make it easier to see the enemy advancing. The military column comes to a halt beside a small hill. The peshmergas jump out of the cars, holding their guns, and file through the rocks to reach the barricades. Those on duty greet the commander and his unexpected guests. The night shift sleeps in a tent pitched beside the pile of sand bags. The horizon appears calm, an arid plain with sand blowing in the wind, the outline of a few buildings far away in the distance. Gunfire isn’t the only danger: the soldiers tell of vehicles that are packed with explosives and sent careering towards the trenches. ‘A month ago it was two diggers and three Humvees,’ the commander says. ‘It was the middle of the night, they generally attack at night, or when it’s raining or foggy, because it’s harder for the air force to operate.’ The Humvee, an American military jeep, is part of the array of equipment ISIS has seized. ‘They have very sophisticated weapons from the Syrian army, the Iraqi army, the American army, the Russian army . . . ’

Back inside the armoured car, the commander won’t take no for an answer: we must stay for lunch at the camp. Good Kurdish food, rice, chicken, soup, vegetables, olives, various fruits. Almost a holiday picnic.

*

Adan, his brother and I spend the afternoon further north, at Lalish, a shrine for the Yazidi, the minority religious group massacred by ISIS in August 2014. By the time we get back towards Erbil, darkness has fallen. Adan and his brother have peshmerga friends near the city who welcome us for supper. They are Kurds who came from Iran, some a long time ago, others more recently, to fight. They have fifty men on the front line and, in a departure from what we saw earlier in the day, twenty-five women. And it is they, in their female uniforms, who, after supper, will bring me a mattress to sleep on, surrounded by flags and portraits of Kurdish heroes.

They speak Kurdish and Farsi and fight for autonomy wherever they are. 28 year-old Shilan, for example, has lost two brothers in combat against Iranian troops, and she joined the Kurdish cause aged fifteen. ‘I was trained by men, we are the first generation of peshmerga women. At first our presence surprised some men, but there are more of us now, our being here attracts others.’

Kani has fought the Iranian army in the past, and ended up here. She is married, her husband is at the front; the women take turns going there, for short stints. ‘We aren’t afraid, we’re used to it.’ Sahar got married but is now committed to remaining right where she is, in the name of the struggle. ‘We don’t want to have kids at the moment.’ An unusual statement in a Muslim context. Shilan has two children, but has only been to the front once. And Aiwan, the prettiest of the bunch, won’t even consider marriage. ‘I’m a peshmerga, I want to fight.’ The primary fight is for independence, but ISIS is the overwhelming emergency. ‘We’re fighting them because we’re humans, it’s everybody’s duty.’

Kamal is a 47-year-old peshmerga who lives in Sweden but returned to train younger generations. He speaks of the strength of ISIS. It is not simply that they ‘combine guerilla experience with modern weaponry’, it’s their courage: ‘What distinguishes them is that they want to die, they are suicidal, they won’t retreat, they’ll stay until the last bullet is fired and they’re merciless.’He speaks from experience: being a veteran guerrilla fighter, he remembers a time before the relative comforts of peshmerga troops, with offices and ministries. ‘We lived in the mountains. We had food only every now and again. I once went forty-five days without taking my shoes off.’

Not to mention the 1980s, when peshmergas were imprisoned and tortured by Saddam’s troops, and thousands of Kurds were exterminated in a genocide committed with chemical weapons, the Anfal Campaign.

*

A day out here is worth ten elsewhere, in part because the sun rises at 4.30 a.m. We bid farewell to the peshmergas and as we travel back to Sulaymaniyah, Adan and his brother talk about what it was like growing up Kurdish under Saddam. ‘Soldiers came and destroyed our houses. Aged six, we sold things in the street to help out at home.’ Today, Adan is an archaeologist, his brother a school teacher. It’s been a long journey. In the early 1990s, when chemical weapons followed countless other attacks by Saddam, they fled Sulaymaniyah for Iran, one hundred kilometres on foot and in the rain. ‘The UN would send supplies to Iran and the Iranians would shift them on to the black market. But there was one day when UNICEF decided to come out to the camp and deliver things by hand and suddenly we were thousands of children running around in bright colours, dressed in pink, red, blue . . . ’

Even with Saddam gone, Adan has few good things to say about Baghdad. He hasn’t received his postgraduate study grant for months, the money frozen by the Shia Iraqi government. Thousands of civil servants have likewise not been paid their salaries. The Kurdistan boom hangs in the air, suspended like the hundreds of buildings we pass on the outskirts of Erbil, whole neighbourhoods left half-built because the price of oil fell, an economic crisis came and ISIS arose.

Along the stunning mountain road, Adan and his brother share another memory: the time they decided to climb these rocks and found them to be covered in land mines, remains from the war with Iran in the 1980s. They had to jump from rock to rock to get back without stepping on the ground.

Meanwhile, at the side of the road, young lads hoist banners honouring Kurdish fighters killed by ISIS.

*

Eleven pairs of boots in the yard. The house is crawling with archaeologists. The cooker arrived, Ana is preparing lunch. The fridge arrived, but not its door: flew off en route. They went to look for it, couldn’t find it, the fridge will have to be sent back to be fixed. There is a table and chairs in the kitchen, a full pantry, crockery, pots and pans. The front room is starting to resemble an office, with tables, computers, a rack full of equipment. In the inside room, mats and strips of foam for everyone, the Oriental Room.

Tiago Costa, the pottery sherd expert who came on ahead with André, offers some perspective – Ana has excavated in Syria before, Ricardo in Syria and Iraq, but João is making his debut in this part of the world, and Mustafa Ahmed, an enthusiastic student who is visiting, is keen to become an archaeologist. ‘The important thing is to treat this as a unique opportunity, appreciate it for what it is,’ says Tiago. ‘Ideally we’ll find a room full of ceramics, but you shouldn’t expect anything.’

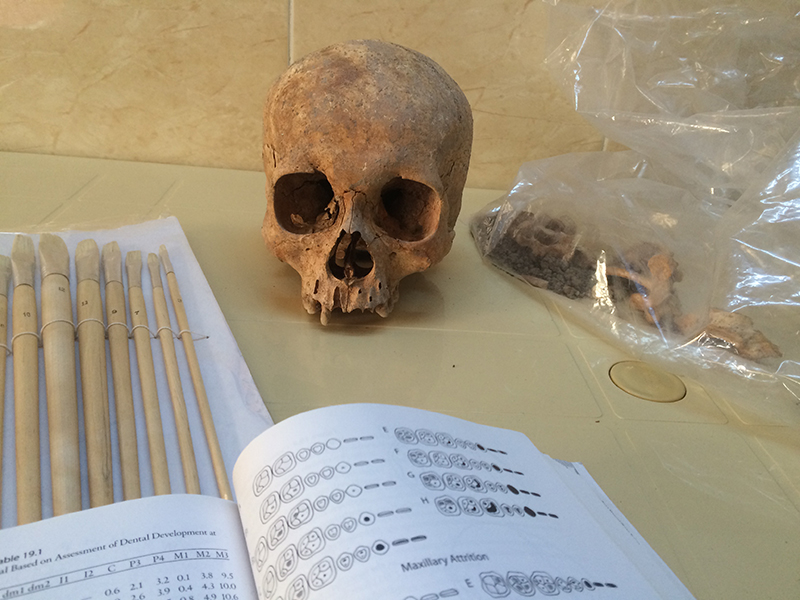

I’m introduced to Awaz Shadan, and Zana Abdulkarim, the two Kurdish archaeologists nominated by the local authorities to live with the team; to Steve Renette, the red-bearded Fleming who is the third project manager, alongside Ricardo and André; and to Giulia Gallio, who will be the anthropologist in charge of bones, an Italian who lives in York and is the most British-tempered person around here.

Steve is linked to the University of Pennsylvania and Ricardo and André are linked to the University of Coimbra. Officially, this dig is a partnership between the two institutions, which take turns to provide funding. Steve secured the budget for 2015, but the three of them are constantly thinking of ways to make the project alive and financially viable. The hill was chosen by the three of them and nobody in the house is being paid a salary. João is here despite being in the middle of his postgraduate dissertation: he’d always wanted to work in the region and was keen to help his friends. The five Portuguese are best friends from Coimbra, having been classmates, flatmates, holiday mates and excavation mates for years. After ten days in their company, one might even consider moving there.

Eleven people at the table. In a commune like this there are only two options, either humour wins out or the lack thereof proves fatal, especially by the end of a month in which they’ll have worked for twelve hours a day, through hernias and exhaustion under a fifty-degree sun. And what happens here is that even Giulia, the phlegmatic one of the group, succumbs and takes off her glasses to wipe away tears of laughter. Ricardo is Coimbra’s own Seinfeld, and Zana the stand-up comedy Viking from Kurdistan, even when sitting down. All this without a drop of alcohol, not even on the night Benfica secures the league title, because alcohol is one of those ‘sensitive issues’ in the neighbourhood.

Awaz introduces black tea filtered with cinnamon sticks, which will become a staple of the household. Glasses and people sprawled about the floor of the lounge, Captain André, the unofficial spokesperson for the team, opens his treasure chest, a bag labelled: ‘KS 13 / 1017 / SF-27’. Translation: KS is Kani Shaie, the name of the hill they’re excavating; 13 for 2013, the year of the find; 1017 is the layer it was found in; SF means Small Findings; 27 is the number of the find.

And there it is, a clay tablet, over five thousand years old, confirmation of how well André, Ricardo and Steve chose this hill. Maybe 5,200 years ago, a man rolled a cylinder-shaped seal into this piece of clay, embossing it with his signature and a clear depiction of deer being transported on a ship. To the right, a perforation indicates the amount, probably ten, a procedure that had yet to be introduced in these parts. We are therefore looking at the birth of bureaucracy, of accountancy, of economics: the first invoice. And an invoice that speaks of relations with Uruk, then the largest city in the world, soon to be ruled by the mythical King Gilgamesh. Perhaps this hill was a colony of Uruk and will reveal how the first cities expanded north, and why.

Steve is wary of so much tea around the treasure and the tablet goes back in its plastic bag. Tiago, assisted by Ricardo and João, spreads potsherds out on the floor as if about to start a jigsaw puzzle. However, nothing can top the image of Giulia giving a skull a good scrub with a toothbrush, teeth included. ‘You can tell from the shape of the jawbone that it’s a woman,’ she says, ‘and she must have been young because she’s got good teeth.’

This dig is not looking for skulls, indeed the team would prefer to avoid them. The problem with excavating is that they have to deal with all the bones of the deceased that have been buried on top of the millennia-old layers, which are the relevant ones in this dig. And because this is not an Indiana Jones movie, nor is it even Max Mallowan’s era, everything the archaeologists find has to be carefully excavated, identified and kept, even if it’s of no interest to the team and only serves to aggravate hernias and weigh on the budget.

Conversation fires back and forth. On hearing that I’ve been to Lalish to see the Yazidi sanctuary, Ricardo, who loves the Yazidis, tells us about the problem they have with lettuce: they associate it with the devil and refuse to eat it. There is a lot of love for the Yazidis in this team. ‘Lalish is my favourite place,’ announces Steve. Elsewhere in the room, someone asks if there’s any rope and someone says there’s enough rope to last ten years; the fridge comes back with a door on; Captain André runs through the list of tasks that are pending: ‘We need to go and extend our visas, we need to go and clear the weeds . . . ’ But only if it doesn’t rain, and the weather forecast is rain.

Meanwhile, the sunset looks promising so the three project managers are reluctant for the day to pass without a trip to the hill. Ricardo wants to face the strimmer he bought at the bazaar, he’s even improvised a shield for his legs out of a cardboard box. In the absence of a protective mask, he’ll be wearing sunglasses instead.

How long it takes to get from Tasluja, the village we’re living in, to the excavation hill is entirely dependent on the checkpoint in between: the delay there can vary between fifteen and thirty minutes. Then the car pulls off the road and goes down a dirt track with greenhouses on either side. We are right in the middle of the Bazian valley, a land that has been crossed for millennia: vast, with gentle rolling green hills, white stone and wheat fields, today it is shadowed by three giant cement factories, slowly gobbling up the landscape and permanently roaring. Not only has this region barely been studied, it is now being dynamited away.

As the sun sets, everything silently turns from green to gold. The sun that appeared in Iran now disappears in Syria, straight ahead, where the gods of Palmyra will soon see black flags. Being here is to excavate against this destruction, a job fit for Sisyphus, constantly starting all over again. For example, thick weeds have reclaimed the hill since 2013, hence the strimmer.

‘Kani Shaie!’ exclaims André while getting out of the car, as if returning home. We climb up. Poppies, wild wheat, wasp nests. There’s a small tree at the top, the view is stunning and pottery emerges wherever you step. ‘It is such a small hill and so people tend not to afford it much importance,’ says Steve, ‘but now everyone is amazed by what we’ve found.’ This is one of very few digs going on in Iraq at present.

‘In 2013, we made a cut that would allow us to quickly get to the more ancient levels,’ explains André. ‘And now we want to further expand each level.’ In other words, each millennium. With his trowel – like a stonemason’s trowel with a diamond-shaped head, only stronger – André digs between the third and fourth millennium BCE (Before the Common Era). Meanwhile, Ricardo buzzes around with his strimmer, fearlessly taking on all comers, be they weeds or flying stones.

André and Steve find more pottery fragments in half an hour than they can carry in their hands. ‘Pottery is our best friend [for establishing periods],’ says André, ‘but it can be our dullest friend too.’ It gets dark. The smell of weeds is intense. Ricardo takes a rest from his travails, then joins in the debate about where to cut into the earth, where to drill further down. It’s the sort of conversation only archaeologists can have: ‘Look, I’m standing in the third millennium,’ one of them says, his foot on a slope. They measure out the land in steps, decide on how many workers they’ll need. ‘We could start with twelve,’ suggests Steve, prudently: that’s twelve salaries out of the budget.

Back at the house, it’s time for after-dinner chit-chat in the backyard, we hear stories from those on scholarships; others teach half the year; others are unemployed after completing €600 internships. Ricardo compares archaeology to astronomy: ‘When we see a star, we are likewise looking at the past; they’re two different types of time machine.’

Kani Shaie is the hill they chose to excavate, which is what they like doing best. Perhaps there is no other way of being in a place like Iraq.

*

Next morning, the whole house sets off to the Sulaymaniyah Museum, where we will be met by Kamal Rahim, director of the Antiquities Service, to whom all archaeologists must report. André, Steve and Ricardo have been nurturing this relationship since 2013, and what they have found since then rather helps. Nevertheless, every time there is fresh bureaucracy and diplomacy to be dealt with.

Good job it’s a big office because, as is the way in the Middle East, there is a never-ending flow of people to be received. Not long after us, three Japanese archaeologists arrive, bearing small gifts, and then a Spanish archaeologist, who has at least one thing in common with all the Portuguese in Sulaymaniyah: he is a big fan of Cláudio Torres, the celebrated Portuguese archaeologist. Women in black serve tea in tiny cups, the sofas are nappa leather, there are photographs of the president on the wall, paper napkins on the table and an Asia Oil calendar.

The director is pulled every which way. While André and the team go off to sort out their visas, which involves providing blood samples, he attends to me in between receiving the Japanese and Spanish visitors. ‘In this region of Sulaymaniyah, there were only two digs in the whole of the twentieth century, one between 1947 and 1955, by the English, another between 1957 and 1959, by the Danes,’ he explains. ‘Saddam’s regime wouldn’t authorise any. That’s why, in 2003, we opened our doors and windows to foreigners. There are remains here that go back to the Stone Age through to the Islamic period, a vast spectrum, and so we try to make it so that every dig excavates a different era.’ André, Steve and Ricardo are focused on the third and fourth millennia BCE. ‘They are the first team to work on that era, a very important one for us, the first cities, the first empires, the relationship between north and south, and they’ve already found many things.’ The results are published by both the Kurds and the international team, but all the artefacts remain in the museum, which is currently the second most important in Iraq (after that of Baghdad). One of the highlights is a superb and unprecedented fragment of the epic of Gilgamesh, only recently identified. The museum building, which has buckets catching leaks, is waiting to be modernised through UNESCO.

The other person foreign archaeologists come to see is the director of the museum, Hashim Hawa. The scene from the previous office is repeated when I go to visit him. The Japanese are already there, handing out more gifts, and here comes the friendly Spaniard. Hashim is also friendly, indeed everyone here’s friendly. Still to come: consultants; clerks; the director’s wife; and the Latvian ambassador has just left, prompting a debate on whether Latvia is the same thing as Lithuania.

‘We want to focus the museum on pieces found here,’ says Hashim after he’s dealt with everyone’s requests without ever losing his smile. ‘Previously, this museum showcased Mesopotamia, it was like the Baghdad Museum. The arrival of foreign archaeologists is great because their finds stay here and knowledge can be pooled together.’ Reading between the lines, he means that Kurdistan wants a Kurdish museum with good local artefacts to put on display, thus affirming itself on a very ancient map while establishing international ties and training the next generation of Kurdish archaeologists.

The director believes that ISIS will not jeopardise any of this. ‘Sulaymaniyah is safe. They managed to take Mosul because they could count on the help from Sunni Arabs in the region who hate the Shia government in Baghdad. Here nobody will let them come and destroy our heritage.’

*

Sulaymaniyah is a sufficiently open city for an old bookseller to declare himself an atheist and sell Nietzsche, Žižek, Dante and Kafka at his stall in the city centre. In the garden next door, friends and family lounge about on lawns, some with guitars, others with dogs. It’s an afternoon free from the shadows of war, or so it seems. Looking a little more closely, we see a father, mother and son crying in a corner. They’re crying, they tell me, because they’re saying farewell. The parents are going back to Syria, the son will remain here having fled the killing in Syria. And the mother keeps on crying and repeating, ‘I haven’t seen my son for two years.’ Each of them is a story in itself.

*

Sulaymaniyah’s open outlook was a key factor in the American decision to open an American University of Iraq here, a monumental campus inaugurated half a dozen years ago, as they’d had an academic presence in Beirut and Cairo for decades. Speaking as a student from Baghdad, and an Arab of Shia origin, Mustafa, the archaeology enthusiast, thinks that ‘In Erbil they wouldn’t let Arabs in.’ His teacher, Tobin Hartnell, a 39-year-old archaeologist with two decades experience working in the Middle East, puts it in more general terms: ‘Sulaymaniyah is the most tolerant part of Kurdistan.’ The fact of the matter is that the Americans deemed it the most secure place in Iraq for such an investment. There are 1,400 students, varying between those who pay $4,000 a year and those who have grants that cover everything. ‘Kurds from Sulaymaniyah make up the majority, but we have people from other provinces, Kurds, Sunni Arabs, Shias, Yazidis,’ explains Tobin, sitting in the ample university cafeteria. ‘It’s probably the only university in Iraq like that.’

Tobin had already packed his suitcase ready to come here when ISIS surrounded Erbil last August. But he didn’t change his plans. He’s married to an Iranian archaeologist and they have a daughter who gets by in English, Farsi and Kurdish. This is the part of the world he chose for himself.

‘For anyone who wants to study Mesopotamia, being in Kurdistan is a priority,’ says Tobin. ‘Every discovery we make is a huge leap forward.’ While the giants Ur and Uruk in southern Iraq have been excavated for a century – ‘and we still don’t know much about them’ – on a small dig here it’s possible to make major advances. ‘Their tell is incredible’, Tobin says, referring to the Kani Shaie hill André, Steve and Ricardo chose. ‘Tell’ is the name applied to an artificial hill formed by various layers of human occupation. ‘What they are excavating is the birth of a civilisation.’

Tobin believes that the Kurdish mountains are going to reveal a whole other Mesopotamia, one that will differ from what we have come to know so far of urban civilisations. ‘What we are trying to see here are empires, not cities. All the great dynasties came from the mountains or fought for control of the mountains, which was where the danger came from. But we still don’t know which civilisation started in these mountains. I think it was a kind of non-centralised civilisation, collaborative, power-sharing.’ He suggests: ‘Federalism may have begun here.’

And if ISIS is a ‘threat to diversity’, then all the more reason to stay. ‘Their destructiveness makes our work more important. There can be no stable future for Kurdistan without archaeology. People need evidence in order to speak about who they are.’

*

The house is up at 4.30 a.m. By 5 a.m., an entire bazaar is ready to be loaded onto the cars and anyone who hasn’t brought a flask, hat, boots, thick trousers, suncream and insect repellent is in for a tough time. With the two cars full, the strimmer will only fit in between Ricardo’s and Tiago’s heads. Inshallah there will be no sudden braking.

The contracted workers are punctual, meaning there are suddenly twenty people on top of the hill. Ricardo, who yesterday tracked down a mask at the bazaar, puts gasoline in his strimmer, others prod shovels into the earth or pull up weeds by hand; everyone does a bit of everything: weed, earth, shovel, bucket. Portugal might even stay afloat if the future of research is this: joy at work.

Hundreds of prodded shovels later, the trowel comes into play to try and establish the contour of the rock, the lie of the land. From where I stand: two scorpions, a spider and a lizard. This is the zoological stage.

By 7.30 a.m., the sun burns, a new hernia is possibly born. It feels like several hours have passed. There is no good position for the back when excavating with a trowel, just least-worst options. Ten minutes rest then back to sticking our noses into a graveyard, because that’s what this top layer is, a series of graves, as has become clear from the arrangement of the stones. First the stones around the skeletons are brushed using a paintbrush and a trowel, then the soil in the middle is carefully excavated, a job so delicate that at a certain point we can no longer use the trowel: we have to switch to a tablespoon, and soon after that to a small wooden spatula. The archaeologist fluctuates between brute force and scalpel surgery, not to mention what he still has to wash, study, photograph and write up.

A femur appears. Then a frog, very much alive, followed by a scorpion. Whether there’s life after death, who knows, but there’s certainly life over death. ‘Some archaeologists refuse to dig up tombs for ethical reasons,’ says Steve. ‘Imagine, you think you’re going to lie there forever, then someone comes along, digs you up and puts you in a plastic bag.’ Which is exactly what’s going to happen to this skeleton as soon as we’ve finished digging it out, a painfully slow process. ‘Cremation is a wonderful thing!’ Meanwhile, Tiago continues shovelling lower down the hill, where he’s been digging away for hours. A grant-less, out-of-work archaeologist can always turn to ploughing fields, the expertise is certainly there.

Alongside this, they are also au fait with 3D photography and quadricopters. Ricardo wields what looks like a PlayStation controller and the drone rises up and hovers like an insect. Propellers poke out from all four corners and there’s a camera in its belly. Its purpose is to take photographs from a great height, but if you didn’t know better, you’d swear it was an extraterrestrial bumblebee. The Kurdish workers lay their shovels down, everyone turns their chins to the sky.

At 9.30 a.m. it’s time for a meal that’s like a first lunch, given that we started work at 5 a.m: a picnic of bread, cheese triangles, cucumber, tomato, fruit, boiled eggs and a half-hour pause under the shade of a tree.

The graves multiply. Giulia and João will spend the next day slumped over excavated bones: shovel, broom, trowel, paintbrush, spatula, infinite patience and care. Some bones turn to dust the moment they’re touched. Giulia is the specialist, but João throws himself into things like there’s no tomorrow, relentlessly. Ana picks up where Tiago left off, performing heroics with the shovel, trowel, broom, bucket, on top of cooking every day for ten people. Last time, André did the cooking, but the consensus is she’s very much the better chef. As for washing the dishes and cleaning the house, there’s a schedule that includes everyone.

Steve and André get together beside another tomb where a cranium is half-exposed. Its teeth look impressively healthy. ‘In the ninth century, people ate a kilo of sugar a year, and this was natural sugar, from fruit and cereals,’ says Giulia. ‘Today we eat sixty-five kilos a year.’

At 1 p.m., we’ve been working for eight hours and the contracted workers finish for the day. Some members of the team go back to the house, but only to eat – a sort of second lunch – before returning: there are exposed bones and they have to be excavated, photographed and taken away; they can’t be abandoned overnight. Those not returning to the hill will clean the hundreds of potsherds found that morning and head into town to buy supplies and remedy the chronic water shortage. Dinner at 7p.m., where Ricardo Seinfeld dedicates the evening’s show to the cement factory nearest the hill. Operated by a global giant, he wonders whether they might want to sponsor the next stage of the dig. In fact he’s read up on them and he knows they have a social responsibility programme, something they themselves have probably forgotten about. Even Giulia, who’s fallen ill from so much sun and hard work, and can’t eat, still laughs.

*

Ricardo came across a family of eleven Yazidis when calling in on the nearest greenhouse to ask if it would be alright to leave a few wheelbarrows and other heavy items there overnight. One of them spoke English, he said, and so one fine morning I go down the hill to meet them.

A precarious-looking house built in amongst the greenhouses, the flies and the heat. Children come barefoot to the door, then Saado stretches out a hand. He’s twenty-five years old and speaks English because he studied engineering at Mosul. Now he’s living in this shack, and that only because he’s alive, unlike the thousands of Yazidis his age who got caught up in the ISIS conquest of the Sinjar region (to the west of Mosul).

Saado had left the village where his family lived and gone to Sinjar to visit friends. He happened to be there on the afternoon that the jihadists arrived. ‘They came with lots of cars – Toyotas – weapons and black flags,’ he recounts, sitting on one of the bits of foam that serves as a bed.

‘We weren’t armed. First they said “You have to raise the white flag”, we raised it, then they divided us into men, women and children and said that everyone had to convert to Islam. Then they repeated this to us one by one and started killing any man who said no.’ They spoke in Kurdish, Saado says, because they knew everyone there spoke Kurdish, but he also heard Arabic and English. ‘They said they were going to liberate us. Liberate us from what?’ He saw them chop off heads and slaughter small children, although they kept the older ones to use as fighters. It went on for hours, there were a lot of people. At eight in the evening it was dark and Saado decided to make a run for it. ‘I thought, if I stay here they’re going to kill me with a knife; if I run there are two possibilities: either I’m killed by a bullet or I escape alive.’ Both seemed better options. He was lucky, walking as far as Syria and then on for another seven hours. But one of his cousins was taken to Tal Afar, in between Sinjar and Mosul, by the jihadists. ‘He told them he’d convert to save himself. Now he can’t escape. We spoke to him two weeks ago and all he did was cry. He says the jihadists do whatever they want and all the people do is listen. They force all single men to fight. He married a Yazidi girl to save her.’ To save her from slavery.

Like so many others, Saado and his family ended up here as refugees. Saado, his wife and two brothers found work in the cucumber greenhouses. They’re paid eighty dollars a month, between them. What would he like to do now? ‘Leave Iraq,’ he replies, smiling at the question. It’s rather redundant to ask him what he needs. ‘Everything and nothing. You can see how we live. I’m an engineer working in a greenhouse. This is an Islamic country and Yazidis and Christians can’t live here.’ Not even in Kurdistan? ‘Even the Kurds sometimes ask why we don’t convert.’ The local government has protected them to a degree, but Saado doesn’t believe they will ever find peace here. He would like to go to anywhere in Europe or the USA.

*

More bones. Neighbours coming up the hill to make sure these are not recent graves. Trips to Erbil seeking missing papers, in vain, two cars breaking down. Sometimes there’s no electricity as well as no water. Sandstorms while recovering phalanges, distal and intermediate. Not to mention the curse of Tutankhamen, when all the archaeologists died after violating the tomb. Because diseases can survive in bones for millennia, Giulia explains.

As for life after death, ‘Who wants seventy virgins waiting for them?’ asks João. ‘Not me.’ It would be too much work educating them all, especially when you’re an archaeologist and you already need to know geography, topography, paleobotany, social anthropology, cartography, photography, information systems, digitalisation, local legislation, public policy, carbon-14 dating, marketing, aeromodelling, strimming and mass catering, all on top of surviving ISIS and Tutankhamen’s curse.

*

The day I’m due to leave Iraq happens to be a Friday, meaning the workers have the day off, so Tobin comes to visit with his wife, their daughter and Mustafa. We travel through the whole valley, passing the cement factories. We go up other hills, those which André, Steve and Ricardo went up before choosing Kani Shaie. There is so much pottery in the valley that we kick it up when walking through the fields. Mesopotamia splintered far and wide. The Iraq of 2015 is no less shattered.

Back in Lisbon, we Skype so that André can show me another sherd, which is not just another sherd. It’s the edge of a vase and it shows three men and a scorpion; it’s from a thousand years after the little clay tablet and, similarly, it almost certainly came from the south. ‘It’s a very important discovery because, contrary to what was previously thought, it shows that there was no break in relations between north and south,’ André explains.

For them, this is still just the beginning. Who knows, maybe they’ll stay and build a house out there. Kurdish TV even transmitted news of Benfica winning the league. Oh, and Saado, the Yazidi, and his brothers have started excavating on the hill. Perhaps they’ll end up in Portugal.

This story was originally published in Portuguese in Público

Photographs courtesy of the author, map courtesy of Público