Robert Macfarlane, the author of Landmarks, The Old Ways, Underland and, most recently, Ness, talks to Adam Scovell, author of Mothlight, who is the director of a film adaptation of MacFarlane’s Ness. They discuss their literary and cinematic influences, the difference between directing and writing and the dramatic scenery of Orford Ness.

Adam Scovell:

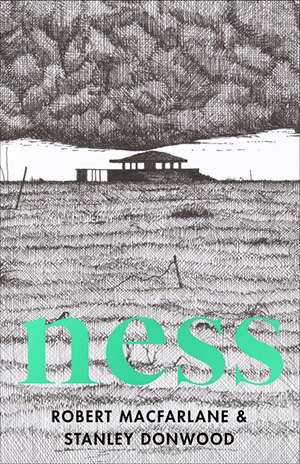

I’m currently in London going through the footage I shot at Orford Ness a few weeks back. It was so stormy on the day that the greys in the black-and-white Super 8 are deeper than almost anything I’ve ever shot. I wish I could get such depths with as much ease in my actual writing. I’m really quite glad though as the artwork for Ness by Stanley Donwood is equally as detailed and moody. I was going to ask about your first experiences of Orford Ness, but, equally, I’m actually intrigued as to when you first met and collaborated with Stanley? Especially as he has now done so much cover work for your books. His Technicolor ‘Holloway’ image for Underland seems to me to summarise so much of what you do in writing; those vivid, sometimes bedazzling yet still authentic portraits of place.

Robert Macfarlane:

I like the – to me – counter-intuitive idea of a ‘deep grey’; that seems just right for Orford Ness, a site of shingle, distressed concrete, sea, sky and, in its past, profound ethical dubiety and archival uncertainty. I first went to the Ness, as I only ever now think of it, at some point in the mid-2000s. As you know, these days you’re ferried over the tidal River Ore by the National Trust equivalent of Charon, and there you are suddenly on the Isle of the Dead, the untrue island, the spit of secrets; an off-shore desert where British munitions and ballistics, including nuclear weapons, were tested through much of the twentieth century. A place whose past is still shrouded by the Official Secrets Act – and which has a power like no other modern landscape I know to work upon, and into, the minds of its visitors. I’ve been back onto the Ness getting on for twenty times since, probably more, including a year spent regularly working there, spending winter nights out in the barracks.

But I only visited with Stanley Donwood two summers ago. Stan spends the summers in a tiny house on stilts without running water or electricity, on a different ness – Wrabness in Essex. The place-name ‘ness’ comes from the Old Norse naze, meaning ‘nose’ or ‘headland’, so there are a fair few ‘nesses’ spread up and down the east coast, including the famous ‘Dungeness’. Anyway, we went out together onto *the* Ness, and – as I knew would be the case – Stan was eye-popped by what he found there; the decaying laboratories, the flatlands of the shingle with its ripples and furrows, the collapsing lighthouse, the ferroconcrete monoliths, the relic traces of a bureaucratised geography of ultra-violence. The Ness is atomic pastoral, a shattered sacrificial-ceremonial supermodern Stonehenge, a ritual space. It was always going to be jam to Stan, the Ness.

Stan and I have been working together now for a decade or so, I guess. He’s now done all but two of my book jackets, including the nuclear-incandescent masterpiece, ‘Nether’, that’s on the cover of Underland. I feel super-lucky to work with him, having all the artistic ability myself of a doughnut. We were brought together by the good offices of the writer Dan Richards, who inveigled us into collaborating with him on a strange, small book called Holloway, which of course you know very well – because you turned it into a brilliant Super-8 short, the film which is the precursor to our Ness collaboration. I remember when you and I were working together on Holloway, we were thinking a lot about the relationship between medium and content, as of course one must, especially with regard to the complex layering of that holloway landscape. But ‘medium’ in your case as a film-maker meant not simply ‘film’, but much more exacting issues such as film-stock, processing and development methods, camera holding and framing. Can you tell me more about the ways these techniques, materials and parameters are made part of your craft as a film-maker?

Scovell:

I imagine winters on the Ness to be enjoyably brutal, rather like its architecture. Staying out there for a long period could be very much Robinson Crusoe territory, or perhaps even Jack Torrance Shining territory. I’ve always imagined doing something similar and applying for a warden job at Blakeney Point in Norfolk; one of those romantic ideas of dropping everything and staying for months in a hut, keeping track of seals and nesting birds. I imagine it would be more haunted on the Ness, of course, with its mixture of manmade and natural landscape. That appeals to me more. I loved on that first filming trip you sent me on, where travelling into the Ness for the first time was exactly like Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker because the ranger drove us into it on that little electric buggy; not unlike that cart that the three travellers in the film enter The Zone on. I actually filmed from that buggy, and you can see in the footage where my father has to prevent me from falling off into the marsh as if the Ness was literally dragging me away with its imagery. Or maybe I just lost my balance . . .

I love Stanley’s work a great deal, and it really is a good fit for your writing. I mentioned to him at the launch of Underland how pivotal his artwork for Radiohead’s OK Computer had been for me. I’d explored and hidden in the edgelands under the M53 in my first few years of secondary school, largely to escape people at lunchtimes. It was this amazing, Tarkovsky-esque place full of ragwort and cinnabar moths but with a bit of extra grit: concrete, burned-out mopeds and dumped couches. Being driven over it used to make me strangely happy, I think I even used to call it the Magic Corner. But then I saw Stanley’s artwork with that motorway stretching and curving exactly like my motorway labyrinth and it just clicked in a way that so rarely happens, like the most bizarre Proustian Madeline conceivable. I think he was quite surprised by me telling him how much that single image meant to me.

I feel like less and less of a filmmaker these days, as I move towards writing fiction. The freedom with writing in comparison to film is astounding when you’ve worked with both (I sneak in visual aspects into my texts with photography anyway). I try to get writers to understand this by telling them to imagine what it would be like if every word they wrote cost a great deal of money to put on the page, and then to imagine there being little opportunity for editing once the words were on that page, aside from structure or tone. Imagine spending the first year of a project not sketching out a draft of a text, but trying to obtain the funding needed to make it; like a writer spending months obtaining a new copy of Word in between bouts of research. Yet I can’t help being drawn back to the potential in filmmaking. Images play with time and place in a way that I think is virtually impossible for the novel to do succinctly. This is why I’ve loved Gilles Deleuze’s writing for a good few years now, and why I ended up using his ideas of time-images for my PhD. He understood cinema’s potential for time-cartography.

I love making shorts, like the one we’ve just finished for our adaption of Ness. They’re almost like fragments or cine-poems as opposed to narrative films. Working on film, with all of its costs, forced me towards this more abstract form. It’s a form that allows place to be explored more deeply as a core theme than in a bigger-budgeted narrative film, especially as people are so often absent from the visuals. That’s why films like Ben Rivers’ Two Years At Sea and Derek Jarman’s Journey To Avebury capture place so well; there’s something natural about their abstraction due to the analogue form. That suits Ness perfectly too.

I’ve been curious about the relationship between making work about a place and then our perception of such places after they have become material. Alan Garner has spoken about this especially well, often in terms of enchantment or re-enchantment. I find that if I’ve visit somewhere that becomes a place in my writing or films, it’s then indelibly cast in that role and gains an unusual resonance (it may just be me!). As you’ve explored and written about so many places, I wondered if that was the case with you (especially as you’ve visited so many difficult places for both work and pleasure, from mountains to caverns)? Do the two intermingle, if there are differences? Does your creative interpretation of a place come to be the chief way you see it, or are there other things that overpower that creative rendering?

Macfarlane:

It’s hard to get away from Tarkovsky (or Ballard) out there on the Ness, isn’t it? The first time I went I felt like throwing flints ahead of me as I approached the labs and other structures, as Red throws nuts and bolts ahead of him in Roadside Picnic (1972), the Strugatsky brothers’ novel that was the inspiration for Stalker, trying to make visible the traps and warped space that exist in the Zone. I guess for a filmmaker Tarkovsky becomes a trap of his own, always threatening to snap you up and confine you inside his vision . . .

W.G. Sebald exercised a similar inspiration-menace upon me for a while, as a writer and especially as a writer on Orford Ness. Sebald went out there during the ‘wilderness years’, between the abandonment of the site by the Ministry of Defence, and the take-over and clean-up by the National Trust, and some of the most intense and oblique scenes of The Rings of Saturn / Die Ringe Des Saturn (1998/1995) occur there. I’ve spent a fair bit of time on pilgrimage, as it were (the German subtitle is ‘Ein englische Wallfahrt; An English Pilgrimage’), trying to match Sebald’s grainy, black-and-white, embedded, captionless photographs with specific locations out there (and often being frustrated by the failed match; which of course becomes a reminder both of the unreliability of Sebald’s hovering, shivering form and of the Ness’s own volatility as a place, always rusting, ruining, shifting in its sleep). So Sebald supplied my Kulturbrille (culture-glasses, in Franz Boas’s coinage) for the Ness for a long while, as perhaps Tarkovsky supplied yours, and it took me a few years to learn to see the place without them, beyond him.

In the end, the inspirations for and influences upon this strange book Ness were much less Sebaldian, and much more Old English and medieval: texts including Beowulf, Gawain and the Green Knight, and the so-called ‘mystery plays’ or ‘miracle plays’ of Middle Ages drama. These mystery plays were told in cycles, in churches and chapels, sometimes over the course of several days. They evolved across the centuries into highly experimental and generically fluid performances, with dramatic tableaux, accompanied by song (especially antiphonal chants), liturgical rhythms and narrative spoken aloud by criers or heralds. Something about the form of these plays attracted me, possibly filtered through T.S. Eliot’s Murder In The Cathedral, and I wanted to experiment with a contemporary version of them, told in similarly mixed ways, but dramatising a technocratic power bent on destruction, subtly overwhelmed by the vibrant matter (to borrow Jane Bennet’s phrase) of the living world.

What confirmed the book to me was my discovery that there was literally a ‘Green Chapel’ on Orford Ness; one of the laboratories where the nuclear weapons were stress-tested had cruciform wall-markings in its sunken test-space, which were used to move the bomb around and then hold it steady, suspended on girders that slotted into the cross-pieces. Since the abandonment of the site, moss, lichen, bracken and elder have slowly recolonised and reclaimed this chapel, where once the physics of death were worshipped. It will never happen, due to safety reasons (the lab is now at risk of complete collapse due to erosion), but my dream would be to have the modern mystery play of Ness performed in that space . . .

Scovell:

I think I’m still menaced by Sebald too. Just this year I’ve written four long articles about him, delivered a paper on him, filmed at Orford Ness and visited his grave . . . It’s going to be a difficult ghost to shake as I’m determined to use photography in my own fiction as well, even though it’s increasingly under very different circumstances to Sebald. In Mothlight I used photographs strictly from one person’s life, inherited from a woman that my grandmother knew. In my current novel, How Pale The Winter Has Made Us, I started with around forty photographs I’d picked up from stalls around the flea markets of Strasbourg, and, as they were all of old Europe, they already had a Sebaldian flavour of sorts. I have mostly removed them to avoid the comparison. And, to get totally away from that, the final in the trilogy of novels I am writing will have Polaroids taken by the character. Sebald is a difficult writer to switch off once his voice is with you, but I’ve found going back to other writers of his ilk – Thomas Bernhard, Elfriede Jelinek and Marcel Proust in particular – has managed to dilute his influence back to something closer to my own prose voice, even if that’s still forming.

Tarkovsky is a little different for me, as I think no one will in any way come close to recreating what he managed to create in his films. The medium has entirely shifted, especially in terms of funding and technology. I think Tarkovsky himself would find it difficult to make a film that satisfied his creativity in the current system of filmmaking. Just imagining the trust required from a studio to allow a director to entirely reshoot a film, as happened when he made Stalker, is as fantastical as the film itself. I also try to avoid watching Stalker these days, especially when editing, just in case it fills me with enough naivety to try to mimic Tarkovsky’ atmosphere. Probably a bizarre thing to say about what is undoubtedly my favourite film, but sometimes it’s best to leave things buried for a while. Stalker is a film that has totally frozen me in the past. Aside from all the other emotions it elicits, there is always a nagging voice whispering ‘You’ll never make a film this good.’

I can certainly see (or more precisely hear) that older influence on Ness though. Even if the imagery is derived from distinctly twentieth-century life and objects, it can’t hide those earlier rhythms. There’s something very material about the language that I associate with those older texts. It’s the same world that I think you can also hear echoes of in the work of Ted Hughes, Seamus Heaney or Alan Garner; that sense of continuity from a crafted, earthy world gone by. I remember Gawain being particularly apt when we first started discussing the project, especially as on that first trip I was travelling from The Wirral, the place ‘where there dwelt but few that neither man nor spirit with good heart loved.’ And it’s interesting that you mention Eliot’s Murder In The Cathedral, as I first came across that in its unusual film version by George Hoellering. Eliot himself voices a templar in the movie, but it doesn’t especially work, and feels rigid. It does things a little too literally, which I hope we’ve avoided in our film version of Ness. Trying to find rotting whale corpses and creatures of mud would make a literal interpretation difficult . . .

Macfarlane:

‘A crafted, earthy world gone by’; that’s quite a phrase. Also – it’s good to see mention of Elfriede Jelinek in there, as we have been speaking and writing almost entirely of male authors and auteurs so far. Let me extend this line of influence by adding the names of Alice Oswald (for her richness and density of sound patterning, especially in Dart; the glottal glutting of speech, and then its sudden sibilant slipping away, with which she makes so much play); also Dorothy Wordsworth, wild-eyed in the best sense, sharp of eye and indeed of tongue; the sculpture and art of Jane and Louise Wilson, who in fact worked on the Ness the same year I did, though I am thinking especially here of the militarised brutalism of their Atlantic Wall series; Ithell Colquhoun’s dazzling surrealism, which I see alongside Nash’s; and the experimental archaeological writings of Þóra Pétursdóttir. All of these very different predecessors find their ways into and onto Ness. Which female cinematographers and directors working in the fields of landscape speak most strongly to you, or have borne most upon your novels and your films?

Scovell:

Interesting that you mentioned the Wilson Sisters as their Ness photographs, Blind Landings, had a huge influence on me when I first saw them. I wrote a poem about that series of photos, which began a series of my own – short poems that responded to artworks I liked. But it was my love of the Wilson Sisters that started that off. I remember as well being on a date in Tate Britain when I first moved to London and several of those photographs were on the wall. I’d been totally unaware they were there, and got so excited that I think my date was quite worried she was with a lunatic obsessed with weapons-testing facilities and terminal beaches . . .

I’m indebted generally to a huge number of women filmmakers, not all of them landscape-obsessed necessarily in the British sense but certainly a great number. Agnès Varda is a huge influence in so many ways; her mischievous curiosity, especially when dealing with place, is infectious, and I think she was really one of the last true greats of the medium. I imagine her films Vagabond and The Gleaners and I would be discussed a whole lot more if she was a British filmmaker. The way they address place and people is astonishing, detailed and yet not overly romantic either. Le Bonheur is also stunning in how it contrasts bright, summer landscapes with a smiling emotional atrocity. I also love the urban landscapes of Chantal Akerman, the rocky outcrops of Margaret Tait, the dream realms of Maya Deren (which seem to me very real as landscapes) and the desolate Trouville beachscapes in winter of Marguerite Duras. Duras never ceases to amaze me with her output; it doesn’t seem humanly possible to have one person create it all.

When thinking of general British responses to landscape in cinema, that to me also seems dominated by women of a sort of newish British New Wave. I’m thinking of the brutal farm landscapes of Hope Dickson’s Leach’s The Levelling and Clio Barnard’s Dark River, Andrea Arnold’s Essex-scape in Fish Tank and the brutality of Brontë country in Wuthering Heights, Penny Woolcock’s coastal essayism in From The Sea To The Land Beyond, the edgelands of Lynne Ramsay’s Ratcatcher and Barnard’s The Selfish Giant (and also Ramsay’s wonderful Deakin-esque short film, The Swimmer). So a pretty healthy, growing number of great filmmakers exploring place in new and interesting ways. I’m sure you could add an equally detailed list of the modern literature equivalent. I know that, for me, the best writer working generally in non-fiction place-writing and essayism is undoubtedly Rebecca Solnit. I love how she weaves so many disparate subjects and ideas together so effortlessly. If I could write something or make a film that achieves what The Faraway Nearby achieved, then I’d be very happy indeed. Every year the Nobel Prize comes around, and every year I’m filled with frustration as to where on Earth her prize is.

Macfarlane:

Strange you should end with Rebecca, whose work I also hold in the highest regard, as she and I once laid plans to set out for Orford Ness together from Cambridge – but never made it, waylaid by a traffic-jam on the notorious A14 before we could reach the coast . . . Since then we’ve walked plenty of miles together here in Cambridgeshire, and indeed among the coastal redwood forests near her home in California – but I would still love to visit the Ness with her, not least because of her own exceptional writing on nuclear test landscapes, and their dispersed geography of harm. This work chiefly comes in a brilliant early book of hers, Savage Dreams, about the Nevada test sites.

I often think of that book – and phrase – when I take friends, students or collaborators out onto Orford Ness for their first visit, and ‘introduce’ them to WE-177a, the parachute-retarded thermonuclear missile that as you know is still present on the Ness (without its physics package, obviously . . .), wheeled around on its green-steel gurney, and which is a central character, if I may call it that, of Ness. People are invariably hushed into silence, awe and something like horror by the encounter with the missile.

There is something frighteningly homely about it; little bigger than a fridge-freezer, a sort of white-goods paint-finish. But it had a maximum 10 kiloton yield (explosive power), 2/3rds the yield of the Little Boy bomb that destroyed Hiroshima on 6 August 1945. And of course the bomb represents the materialisation of a much vaster nuclear geography, stretching from the British test landscapes at Maralinga, South Australia, and on Christmas and Malden Islands in the Pacific, as well as the uranium mining and enrichment infrastructure spread across Africa and England, among other many countries, and the shifting archipelago of nuclear submarines roaming the oceans. There is a banality to the missile’s evil. Like the Ness as a whole, it condenses ‘savage dreams’.

Robert Macfarlane and Stanley Donwood’s Ness is available now from Hamish Hamilton.

Images © David Levenson and Influx Press