Aesthetic debates invite political investment. Before Stalinism, Adorno claims, modernism in the arts was more than compatible with revolutionary politics. In the Cold War, abstract expressionism became a weapon in US foreign policy, to the chagrin of the henceforth marginalized WPA muralists, social and magical realists, storytelling painters of all kinds. In Germany, Günter Grass, himself no mean draftsman, complained bitterly about this tyranny of the abstract in his autobiography. An intense German polemic over figuration, however, had to await reunification, when the most interesting East German production – the so-called New (or Second, or Third) Leipzig School – became caught up in this already fraught symbolic quarrel. So it is that the most prolific of these figurative painters, Neo Rauch, a veritable Balzac of the storytelling image, has run aground of attacks reading him alternatively as ‘East German’ (that is, communist) or national-fascist, inviting his own unnecessary (political) self-defense of what Thomas Mann called an ‘unpolitical man’.

Panorama Museum. Bad Frankenhausen, Germany. Shutterstock

Political or not, the element Rauch works in is certainly what we call History. This is rare enough in an ahistorical late capitalism in which only the extremes of Left and Right retain a keen sense of historicity. The pieces of the past that drift down into Rauch’s canvases, however, are too fragmented to bear much in the way of a political charge. He tells us that they come to him at night, imperiously soliciting expression; and what they preeminently express is the fragmentation of German history, which, at the center of Europe, experienced war on many fronts, from the Roman Empire to the Thirty Years War, and on into the long and bloody twentieth century. Their representations demand a reunification they can only find on the canvas and through the energetic interpretations of their beholders.

Rauch’s canvases may be oneiric, but we must be careful, however strong the temptation, not to assimilate them to surrealism, which was marked, I would like to say, by a quintessentially French, and even Parisian, unconscious, however worldwide its later diffusion, and despite illustrious German adherents such as Max Ernst (Rauch’s daytime self, an eloquent commentator and theorist of his own works, parries with the more Germanic figure of Max Beckmann).

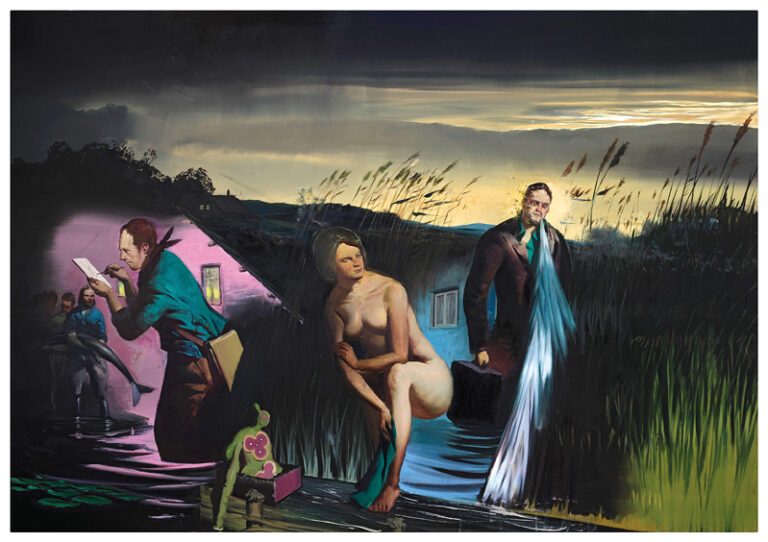

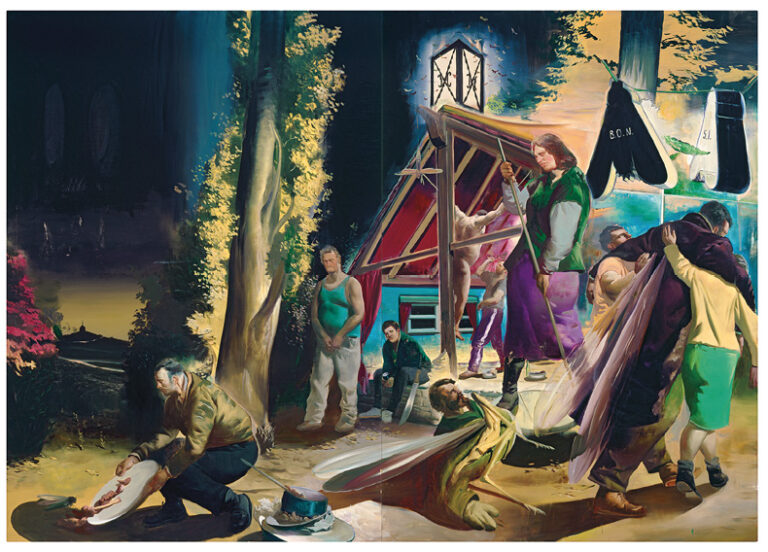

Schilfland, 2009

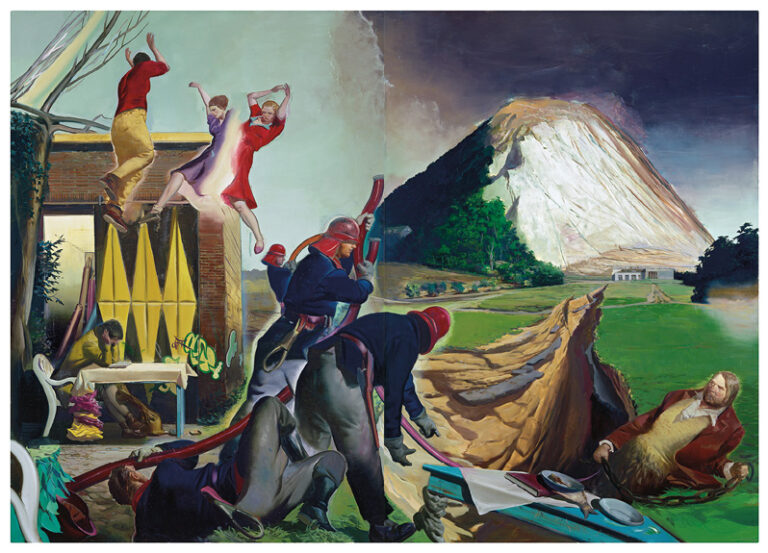

Die Fuge, 2006

What Rauch has in common with surrealism is a rigorous method paradoxically called ‘free association’, a practice which aims to release a flow of images otherwise blocked by Freud’s ‘reality principle’. Rauch also retains the practice of the surrealist image as Reverdy defined it: ‘a juxtaposition of two more or less distant realities. The more the relationship between the two juxtaposed realities is distant and true, the stronger the image will be . . .’ In Rauch this ‘juxtaposition’ – far too mild a word for his crashes and dissonances, his Ovidian metamorphoses and his inexplicable gaps – is the crack through which a genuinely historical contradiction seeps like radiation.

Saxony and its capital Leipzig – almost as distant from GDR Berlin as from the multiple West German cultural centers – bequeathed the painter a stock of raw materials: the images of defeat. The very landscape – a non-Rust Belt terrain of the undeveloped rather than the overdeveloped, not the exhaustion of Detroit so much as the vacant lots of forced abandonment – is shaped and defined by projects arrested in midcourse: graveyards of appliances which did not have time to be worn out by the daily life of a successfully industrialized society: unfinished houses, incomplete electrical grids, pipes, tools, excavations for never-erected buildings. This essential historical incompleteness now releases all the ghosts of an unrealized past, who wander through the paintings in their outmoded (generally Romantic) costumes, alongside survivors whose unoccupied gazes betray their lack of connection with one another. Instead we find disembodied clashes, disinterested thwartings, a violent dramaturgy of the distracted and the uninvolved, rebus, caricature, cartoon, historical pageants, the dramatic opera of enigmatic encounters, a staged charade of the freeze-framed moments of a past that went nowhere. Chekhov offered us a stage full of characters talking to themselves rather than each other. Here we have whole historical periods which have nothing to say to one another, and yet just as strangely fight it out.

It was not always so. Rauch belongs to the younger Leipzig generation that began by experimenting with strange sci-fi constructions, and a minimum of human inhabitants (whether operators or victims). In his early work planes of repressive material intersect: constellations of objects that contradict social physics, while a sci-fi robotic space asserts its primacy. All these expressions of ‘dissidence’ preoccupied Rauch and his generation in the early years, in an appeal of willpower to generate new styles and new gestures. At some point, around 2000, Rauch found the more congenial path of narrative – of characters and incomprehensible stories and interactions – preferable to playing with spaces that recede into backgrounds of stage direction and scenery.

The older generation did not know this kind of release. In the twilight years of the GDR, one of Rauch’s elders, the great historical painter Werner Tübke, commemorated the history of Germany’s revolutionary defeats in a memorial to Thomas Müntzer and his peasant army, crushed in 1525 at the battle of Frankenhausen. There, an immense circular building houses Tübke’s well-nigh encyclopedic Renaissance-style fresco worthy of Diego Rivera, nothing less than a history of the world, whose religious elements alienated the party which so generously financed it. (Erich Honecker refused to attend its inauguration.) Isolated in an East German landscape where it remains difficult to access, this impossible tourist attraction is yet another remnant left behind by an abandoned future, like the Hindu and Buddhist caves scattered through India. Tübke thereby authorized a representational style which would entitle Rauch to claim an apolitical indifference.

Do we then find in Rauch’s work a ‘surrealism without the unconscious’? Not exactly. But I would argue for a form of the ‘unconscious’ which Derrida, following Freud on melancholy and the later theorists Nicolas Abraham and Mária Török, called ‘encryption’ – the formation of a kind of cyst or crypt within the self of unliquidated entities, in which historical traumas bide their time, unassimilated, unincorporated, prepared at any moment to reemerge as fresh ghosts demanding their representation on the painted surface. The process indeed may be compared to reality itself, when a wealthy West Germany annexed its socialist sibling without any genuine assimilation, leaving the latter as the source of violent drives and impulses incompatible with the Americanized culture of an officially reunified Germania. Here, if anywhere, we may situate the allegorical temptation that threatens Rauch’s work.

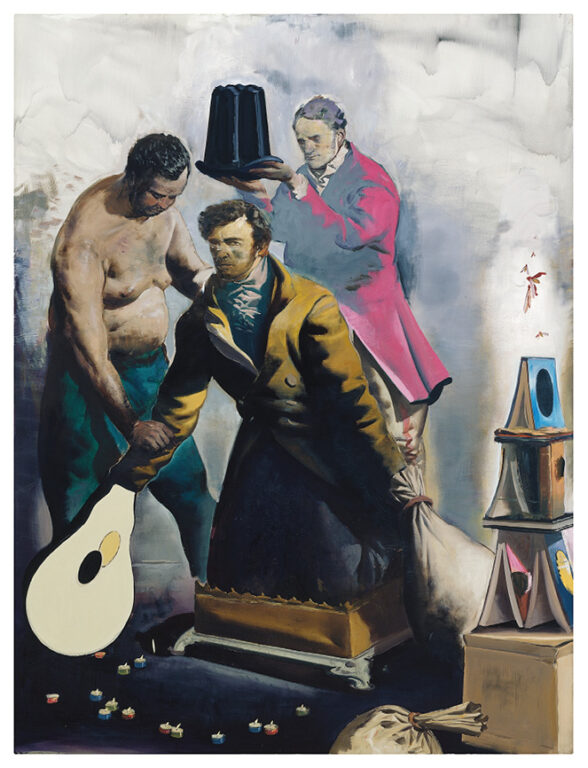

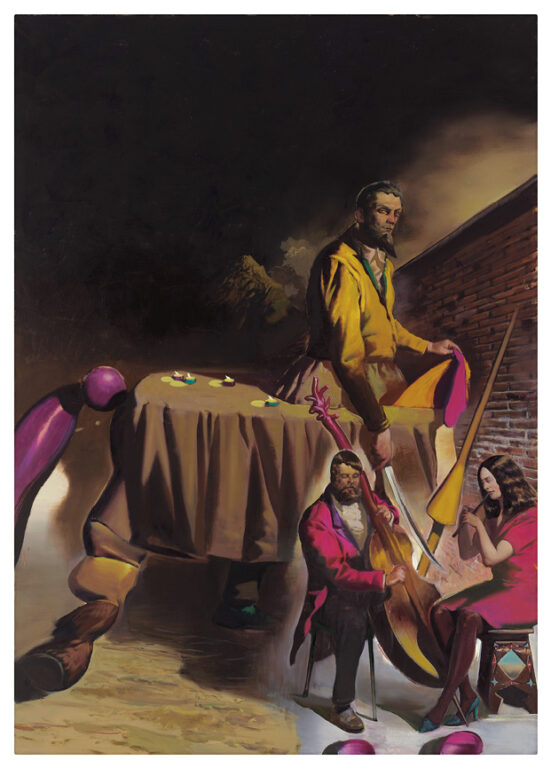

Krönung I, 2008

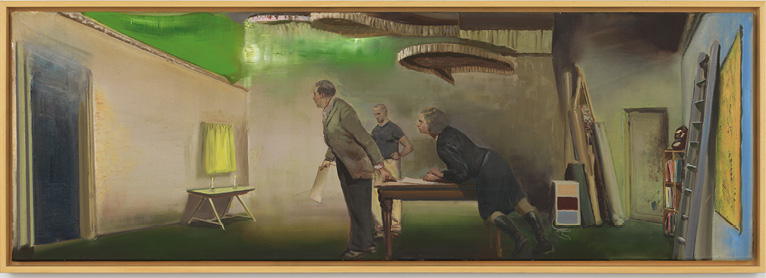

This work, after the youthful period described above, which one can scarcely characterize as ‘dissident’, may be divided into episodes and scenes: the simpler but not necessarily smaller works, organized around what looks like a single theme, and the monumental paintings in which a whole variety of thematic groupings are scattered across the canvas, at their best in a kind of orgiastic spectacle which the viewer is called on to unify – but not too quickly! – so as not to lose the dissonances and the quintessential fragmentation. Indeed, with Rauch, it is always best to see a roomful of these productions in order to register their common populations and their family likenesses rather than to commit one’s viewing to the discipline of a single ‘masterwork’.

The war between representation and abstraction presupposed, at least among the adherents of the latter, that you could simply peel off storytelling and its accoutrements from art and attain a purer and more intense relationship with the fundamentals: oil paint, colors, geometrical shapes. The result would achieve that stunned fascination called aesthetic pleasure. But this is to ignore a different kind of dynamic of formal ‘separation’ within Rauch’s ‘storytelling’ itself. His characters rarely look at one another, each lost in a world apart; the groups are isolated from one another and from their surroundings; even the often monstrous evolution of ominous objects takes place in isolation. Yet all this is also happening to the raw materials of representation as such. In an episodic painting like Krönung I (Coronation I, 2008) – particularly if you have the good luck to see it in reality – the colored paint of the costumes, the brownish yellow of the ‘pretender’, the gray and red of the officiant, rise off the garments which appear to glow from the inside with their own inner being. The recurrent combinations of these autonomous colors – midnight blue, indigo, rust red, purple, a strident yellow – blot out the air and light of an open sky, and seem to make of our contemplation of the painting a kind of grotto. The yellow in particular becomes a character in its own right, like a kind of shriek: it is given the honor of its own portrait in a painting like Paranoia (2007), where an anxious couple await the opening of a yellow curtain, while the completed revelation – an almost wholly yellow canvas – hangs on the wall behind them.

Paranoia, 2007

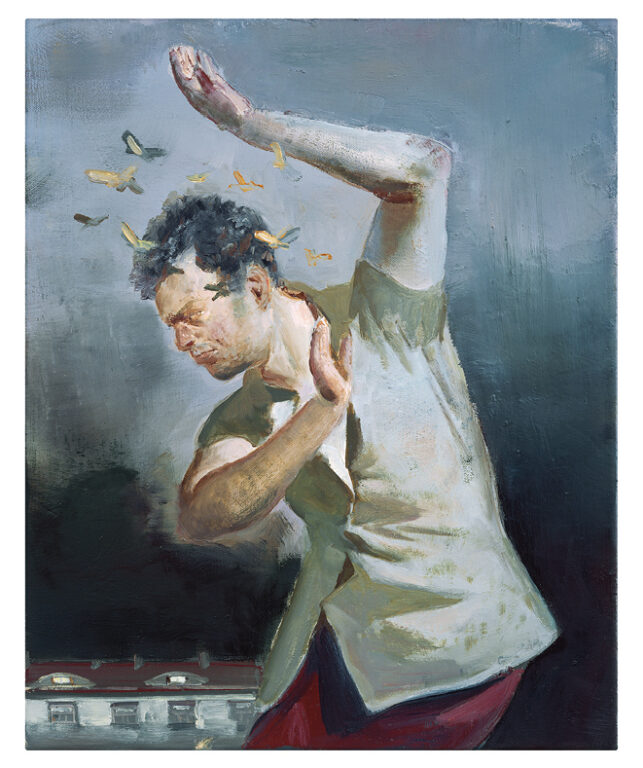

Rauch’s separation of objects from one another is confirmed by their reunification in transmutations of all kinds – the extremities of the heir in Krönung I turn out to be a money-bag on the one arm, a monstrous lightbulb on the other. Figures emerge from the earth or disappear back into it, as in Die Fuge (Flight, 2007). Human faces begin to grow on strange animals. We follow the inner potentialities of rods and staves from painting to painting, where everything latent in the word squirming becomes at one and the same time hoses, eels and intubated tubes, before returning to their vocation of holding off bodies or bloodlessly intercepting or wounding them. Then there are the gnats or fireflies, whose avatars are little candles and which torment faces like that of our monarch-to-be or, better still, the magnificent portrait Ungeheuer (Ogre, 2006). A terrible evolution – angels or insects – is ratified by the fully grown post-human winged figures assisted offstage in Bon Si (2006). Mixed figures abound, as in the cynically observant table-centaur who dominates a musical duo in Reiter (Rider, 2010). I am even tempted to say that here, as in Brecht, there is an autonomy of the gesture: the multitudinous figures are so many, supports for the gestures which they hold as in a tableau, each unrelated to those of their neighbors. And to be sure, what unifies the heterogeneous content of the scenes is often their preparation as a spectacle, meant to be viewed by an absent public. Thus, in Interview (2006), the two interlocutors, as limp as corpses, are vainly held in place by stagehands obedient to offstage commands.

Bon Si, 2006

So it is that, whatever the content of the great scenes – pageants, assemblies, arsons, Volksfeste, a market, a construction site – we the viewers, alongside the occasional presence of the lone artist in the corner, are also built in and called upon to invent the unity and identity of these batches of uncoordinated figures and elements. Sometimes the omnipresent titles (or subtitles) have enough authority to nudge us in a satisfying direction; and sometimes not. These are, as it were, the cold cases, the unsolved mysteries, to which as detectives we return again and again: Schilfland (Marshland, 2009) for example, where a frieze of incommensurable spaces leads us across the swampland of the title. We begin on the left with a grotto, in which workmen standing outside houses with lit windows hold a giant fish (the avatar perhaps of those wriggling staves we mentioned: frequent inhabitants, nightmarish or not, of Rauch’s paintings). This hollow space is not redeemed by a draftsman presumably sketching its cavity from its outer edge. Meanwhile, across the swamp, a naked woman inexplicably floats on open air (there are few nudes in Rauch), and a man strides through the water, his face bedeviled by those same gnats I mentioned above. A sheaf of swamp leaves comes out of his mouth, and he holds what looks to be a typewriter case. This figure seems to me the most tragic in all of Rauch, his darkened eyes betokening some lost emotion, his inexpressive face an enigmatic mixture which we cannot identify and for which we have no words. Here too a facade with lighted windows seems to consecrate a combination of typically German elements we cannot fathom, while in the front a strange little cartoon figure, its midriff opening in a Daliesque drawer as an appendage, dances joyously to the impossibility of representing any kind of transition from these recessive spaces to the swampland between them. Need I say more?

Reiter, 2010

A scene which ought to be more allegorically readable, Die Fuge, gives us imprisonment at one end and release on the other. Firemen appear to be excavating in the middle, throwing up the masses of dirt which open a kind of earth-tent for the shackled prisoner whose beard-mask appears to mark him as some kind of (nineteenth-century) anarchist threat, which allows us to conjecture that the dirt pile is in reality a demolished house among whose tiles the firemen are working. At the other end, a pair of conjoined twin girls rise ecstatically into the sky à la Pasolini accompanied by an indistinct male companion, brother or otherwise, against the background of a solid frame which may well be destined for another demolition. Within it, against the background of what may be surfboards or Picasso-style African masks, a youth is placidly reading, surrounded by a few of those blobs which in Rauch designate the limits of expression. A fireman has been flattened in the foreground along with a table, while in the distance a truly massive mountain sets the scene. But the scene for what?

Bergson thought the past was an immense cone whose moving tip wrote the present, its simultaneous contents interrelated in such a way as to stretch back into pre-history. So also this art, in which centuries of German history elected this particular set of haptic eyes and visually instinctive hands to serve as a painterly conduit for a stream of images, the unrelated fragments of a discontinuous collective experience. Maybe all art is that; or maybe unique circumstances are required for a Neo Rauch to fulfill what is certainly a historic destiny.

Ungeheuer, 2006

Artwork by Neo Rauch, courtesy of the artist, Galerie EIGEN + ART, Leipzig / Berlin and David Zwirner and photographed by Uwe Walter