Renderings

Edward Burtynsky & Anthony Doerr

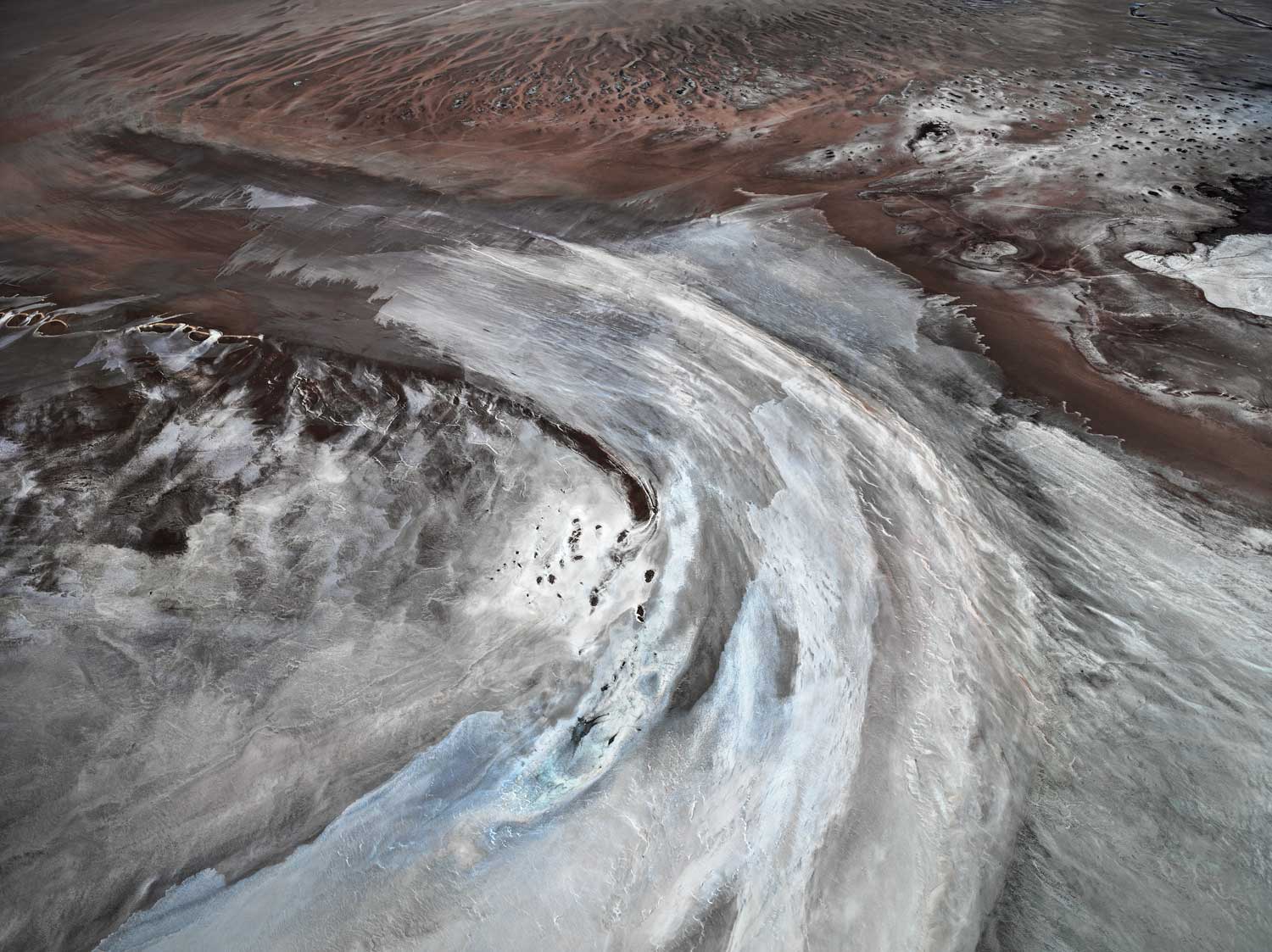

For over three decades, the Canadian photographer and filmmaker Edward Burtynsky has been traveling the planet making astonishing images of landscapes. He takes them with large-format cameras from godlike, elevated positions in remote places like Iceland or the Baja Peninsula or the Niger Delta.

But these are not nostalgic visions of untrammeled nature, destined for office calendars or iPhone backgrounds. No leafy asters bloom against backdrops of sawtoothed peaks; no toucans emerge from dark canopies to wag their bills.

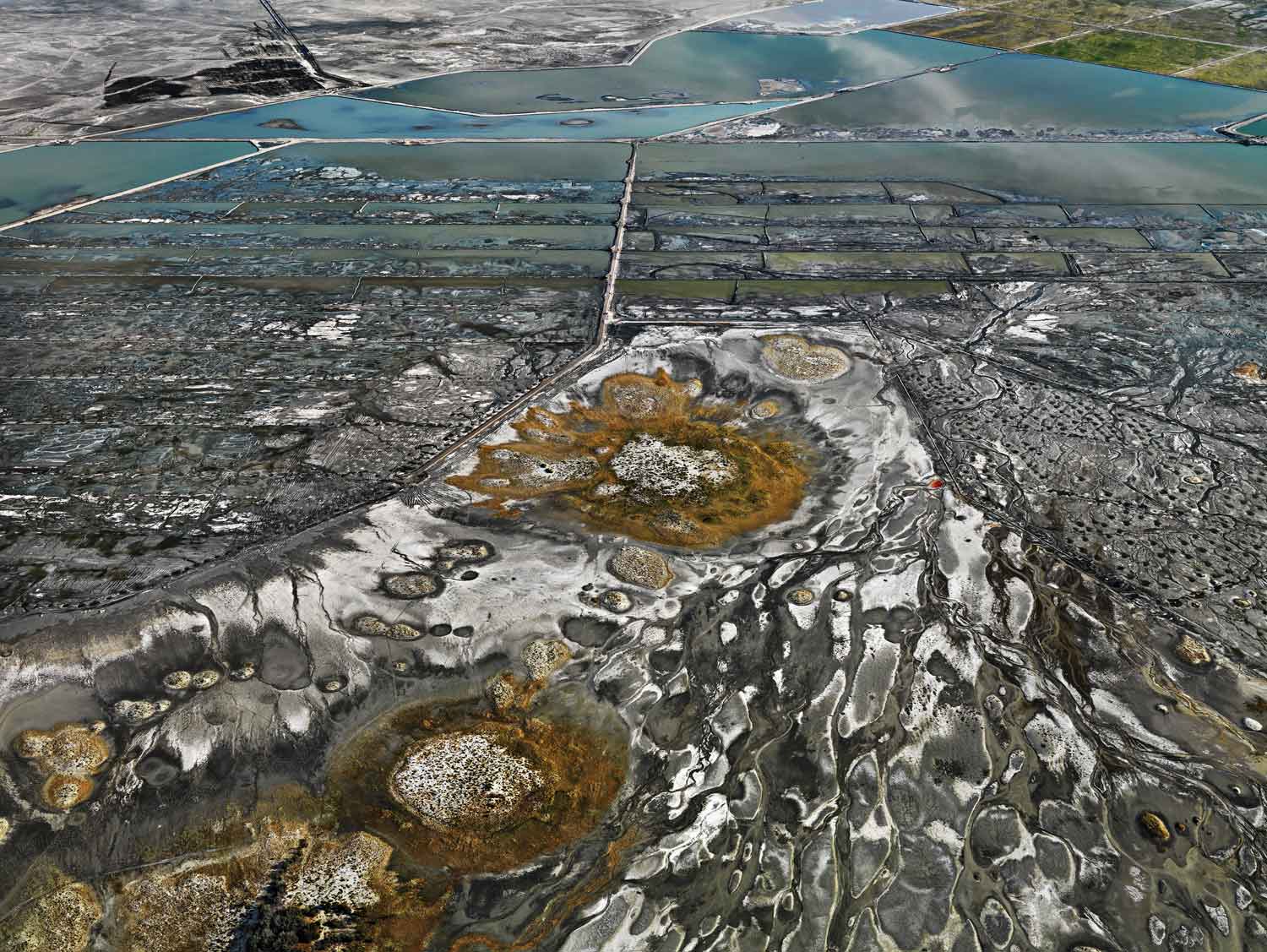

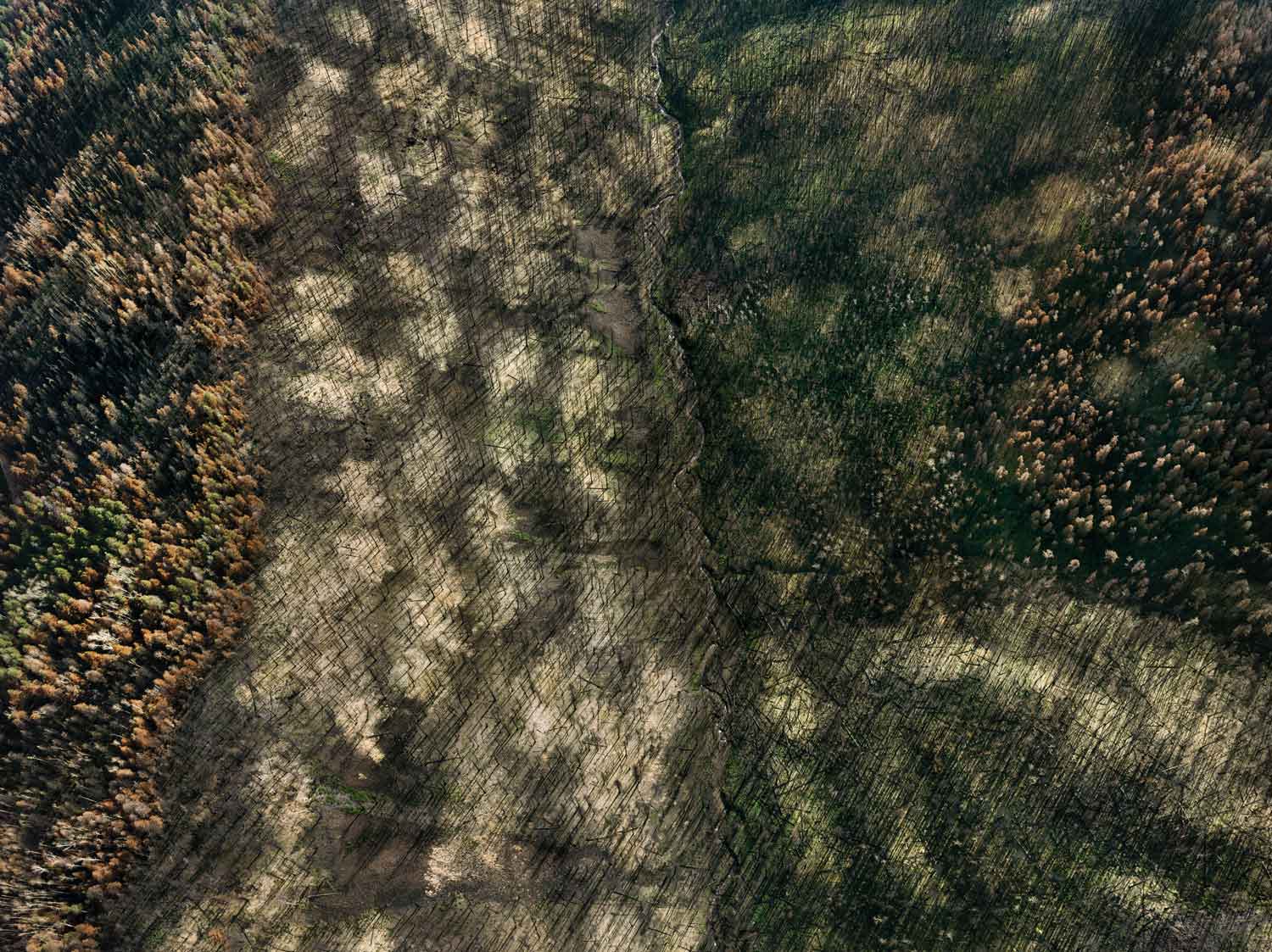

In Burtynsky’s landscapes, we see the Earth we live on right now: a place humans have hacked up, carved up, blown up, spilled on and recycled. Bright orange tailings from a nickel mine wind through gray Ontario mud. A canyon of bare dirt twists between walls made by hundreds of thousands of discarded automobile tires. An oil spill spreads a gorgeous blue splotch across the sea.

Burtynsky shows us suburbia pressed against wetlands, supertanker graveyards in Bangladesh and parking lots so big they challenge comprehension. His best photographs are expressionistic, almost calligraphic, as though he’s displaying the hidden signatures our collective appetites have etched across the Earth. They are startling, frozen pictures, sometimes remote, sometimes intimate, sometimes both at the same time.

I find them repellent. I also find them beautiful.

*

Not so long ago, a reader waited in a queue to meet me after a public event. The gentleman shook my hand and told me that he enjoyed the beginning of a novel I’d written. I braced myself, then did my best to maintain eye contact while he explained that he detested the ending of this particular book (near which one of the protagonists dies).

‘What,’ he wanted to know, ‘was the purpose? What was the point?’

I’m afraid I mumbled something like, ‘I just tried to tell the story as carefully as I could.’ But later that night, tossing in my hotel bed, I had so many purposes! So many points! I wished I had told him that I wanted to show how hard war was on the young, how technology can be a force for oppression and for liberation, how all lives, even the smallest, are worth investigating.

I wished I had told him that I had wanted to make something both repellent and beautiful.

*

Often when I stare into the alien circuitry of a Burtynsky picture, it takes me a while to figure out what has actually been photographed. Is that a rock quarry, are those tiny figures people, are those oil pump jacks?

For a moment it becomes a sort of game. And then, after I manage to puzzle out several of his images – a forest of Shanghai skyscrapers, say; then a quilt of Spanish olive groves; then the ruins of a Mexican shrimp farm – I am inevitably confronted by simultaneous awe and despair at the scale of what our industries are doing to the Earth. The pressure that 7.6 billion humans are putting on the planet becomes visual, becomes emotional.

‘I want to use my images,’ Burtynsky said in his 2005 TED Prize acceptance speech, ‘to persuade millions of people to join in the global conversation on sustainability’.

This is not the most fashionable sort of statement for an artist to make. We tend to shy away from any creative work that tries to nudge us in a political direction, particularly if it’s in a direction we’re not already traveling. If art tries to be moral, goes the argument, then it’s not artful. It’s didactic.

Here’s Garrison Keillor, from his introduction to Best American Short Stories 1998: ‘A story that carries its lesson under its arm is immediately distrusted.’

Here’s Mary Gordon writing in the Atlantic in 2005: ‘I believe that if your primary motivation in life is to be moral, you don’t become an artist. You do good works.’

And yet, doesn’t the elevation of certain images or certain stories over other images or other stories involve moral judgment? Each time we arrange things within a frame (whether the frame of a camera lens or the boards of a book) don’t we, simply by the acts of inclusion and exclusion, make a near-infinity of moral calculations?

Do Burtynsky’s photographs make you think about scarcity and abundance? Do they make you reconsider the life cycles of the stuff around you – your home, your computer, your shoes, your toaster, your olives, your popcorn shrimp? That’s up to you.

What’s the purpose? What’s the point?

I should have told that gentleman the same thing Burtynsky’s photos say to me every time I see them.

Look at this, the pictures say. See this. This is happening. This is where you live.