Norah and Reginald meet at a tennis club in east London during the Great War. Reginald has an elegant backswing. Norah has a powerful serve. They play doubles. They play each other. They strike up a romance and get married. Reginald is a clerk in the Westminster Bank. He has a horsey face, long and sad, with spectacles. He is anxious by disposition. Norah is bossy. She has a swarthy complexion and volunteers for the National Relief Fund. She comes from a family who bettered themselves and lives in a house with three floors and two maids who sleep in the attic.

Reginald buys a large house in Blackheath with the help of Norah’s father. Beryl is born first, and then Ray in 1921, three years later. She is going to be named Pamela, but after she’s born she does not seem like a Pamela and so they name her after an uncle, Captain Wray, who was killed in Gallipoli. Ray contracts polio when she is a few months old. She is not too sick but her right leg is damaged and a physiotherapist called Miss Gedge visits once a week to do exercises with baby Ray on the billiard table. When she is two, Barbara is born. Ray’s earliest memory is of baby Barbara in her treasure cot. It has pearly white sides, a lacy canopy and trailing silk ribbons. It rocks gently on the floorboards of the nursery as Ray peers inside.

Barbara is her mother’s favourite. She is a timid child who carries her toy farm animals everywhere she goes, stuffed into the pockets of her cardigan. Ray is her father’s favourite. She is short-sighted, like him, and studious. Ray and Barbara are natural comrades, united by their fear of Beryl, who is stubborn and imperious. Beryl is nobody’s favourite, but she is the most beautiful of the sisters. She has her father’s height and her mother’s aristocratic features. Reginald is promoted to bank manager. He buys an old Crossley motor car and every summer they go on their holidays to Birchington-on-Sea. Norah is the driver; Reginald navigates. They always argue on the way. Norah knits beige bathing suits for her daughters and Reginald rigs up a curtain that can be pulled around all the windows of the car to hide them from sight while they are changing. Ray loves the sea – the sweeping strand, the smell of salt and weed, the vacillating tides.

Ray, Barbara and Beryl c. 1926

Ray is the only sister to win a scholarship to boarding school. Norah drives her down to Sussex with a small trunk of necessary possessions. Barbara waves ferociously out the rear windscreen of the car as it heads back to London. Ray is lonely at first and teased for being a scholarship girl. When her parents come for day visits she is embarrassed that they pack a picnic lunch instead of taking her out to a hotel. Beryl leaves school early. Reginald gets her a job in the income tax section of the bank and in her spare time she does in-house modelling jobs for a ladies’ clothing boutique. During the holidays Ray and Barbara dance to the gramophone in the dining room and play tennis at the club where their parents met, eyeing up the young men. By the time Ray is a senior her best friend is an Irish girl called Lana. In the evenings they play cribbage and Monopoly with the other senior girls in the common room. On the night that Edward VIII abdicates, they are allowed to gather around the wireless. Ray doesn’t approve, though she thinks Mrs Simpson is very chic.

At elevenses on Sunday the 3rd of September, 1939, Neville Chamberlain declares that England is at war. Air raid sirens sound across London immediately, and everybody scrambles for shelter, but there are no bombs. There are no bombs for almost a year. Beryl and Ray learn to drive and volunteer with the Young Women’s Christian Association to transport mobile canteens around the city. Hundreds of Zeppelins appear suspended in the sky over London, tethered to steel cables manned by members of the RAF’s barrage balloon squadrons who live in huts on-site. The canteens contain tea urns and currant buns and Woodbine cigarettes. Ray likes to prop the window open and lean out to chat to the men as they take their breaks.

Men are becoming scarce. The sisters are allowed to have their friends and boyfriends around for afternoon tea at the weekends and they play ‘sardines’ in the rooms of the rambling house, kissing in cluttered wardrobes. Barbara finishes school and follows Beryl into the bank and falls in love with a golden-haired Royal Engineer called Keith. Ray gets engaged to Ralph, who has a claw hand and a little green sports car that he drives too fast. On Christmas Day in 1940 he crashes into a delivery van on the way back from lunch in Blackheath. Ralph breaks his nose against the steering wheel but Ray, who is in the passenger seat, is flung through the windscreen and lands in shrubbery on the side of the road. Barbara and Keith ride with her in the ambulance. Barbara holds Ray’s hand and Keith holds Barbara’s hand. Ray is unconscious for three days. When she wakes up she finds that her two front teeth are missing and Ralph has broken off their engagement.

By then bombs are normal. When the air raid sirens sound the nurses on Ray’s hospital ward distribute enamel washbowls and push all the beds into the middle of the floor to make an island. Then the patients put their pillows over their heads, and the washbowls over their pillows, and the nurses clamber underneath the island of beds. Somebody tells Ray that if you can hear a bomb falling then it will not hit you, and so she tries to be comforted by this.

Ralph’s mother feels bad about her son’s behaviour and invites Ray to convalesce at their house in Hampshire, safe from the London bombs. Ray spends six awkward weeks in the wintery countryside. She sits up in bed looking out at a bare sweet chestnut tree and reading novels, Gone with the Wind, Tender Is the Night and Cold Comfort Farm. Every now and again a piece of her splintered jaw surfaces somewhere in her mouth and she spits it out like an apple pip. Spring finally comes and Norah arrives in the old Crossley to collect her daughter. Then she forces Ray to drive all the way back to Blackheath, so that she will not be afraid.

Barbara marries Keith in 1943. She wears a dress borrowed from one of her friends in the bank. They have soused herring for their wedding dinner. Then Keith is sent to Normandy to clear landmines. Beryl and Ray volunteer to join the Women’s Royal Naval Service and are posted to Dover to become motor transport drivers. Beryl, who has a habit of impressing her superior officers, is chosen to be the admiral’s personal driver. She becomes solely responsible for his silver Rolls-Royce, whereas Ray is assigned a new vehicle every week. In Dover Ray drives trucks delivering supplies, and ambulances collecting casualties from troop ships, and cars escorting the family members of soldiers who have been killed. After two years both sisters are promoted. Beryl, tired of the officers who insist on sitting in the front seat of the Rolls-Royce and stroking her left knee while she is driving, goes into the administration department and Ray, who fancies herself a spy, goes into the intelligence service. They have just finished general training and are waiting to be posted when they hear that Reginald is ill.

Barbara, Norah, Beryl and Ray, c. 1938

Reginald has retired from the bank and is staying with his sister in Chester when he is diagnosed with a duodenal ulcer. He is admitted to the local cottage hospital for a simple operation. The doctor gases him to sleep and he never wakes up again. In the same week Barbara receives a telegram to say that Keith has been wounded and is in hospital in Basingstoke. He has a leg injury and a fractured skull. Barbara finds him sitting up in bed with a huge, white bandage wrapped around the golden hair on his head.

In the intelligence service Ray is posted to the Shetland Islands. She is astonished by the beauty of the bleak scenery, the grey stone buildings, the omnipresence of the sea. Ray searches for spies and attempts to intercept German codes. She assists with the testing of human torpedoes and operations that involve sending midget submarines to the fjords of Norway to surreptitiously attach limpet bombs to the hulls of enemy battleships. In the last year of the war Ray is recruited to Lord Mountbatten’s staff and posted to Ceylon. She spends four exciting but uncomfortable weeks on a converted merchant ship. It travels down the Suez Canal and through the Red Sea. It is so hot and squashy that Ray carries her mattress up to the top deck at night and stretches out between the funnels. The ship has almost arrived in Colombo when news of the Hiroshima bomb reaches them. By the time they dock, the war is over.

In Ceylon the Women’s Royal Naval Service officers wear white cotton uniforms and sleep beneath mosquito nets in rooms with walls that don’t reach all the way to the ceiling. At night they hear jackals prowling outside. After five years of war, it feels like a holiday. Ray goes swimming and eats pineapples and smokes Lucky Strikes with the Americans. After three months she is sent to Singapore in a Sunderland flying boat.

Back in London Beryl is promoted to first officer. She has grown stocky and learned to sew. She is allowed to stay in the WRNS, whereas Ray only ever makes third officer before she is demobilised. When she finally arrives home she thinks she has a very fine tan. Barbara gives her a hug and declares that the colour of her skin is, in fact, mustard yellow, which turns out to be a side effect of the antimalarial tablets. In 1945 Barbara opens a toy shop in Blackheath called Raggity Ann’s. It sells high-quality wooden toys, porcelain dolls and model plane kits. The shrapnel is still lodged inside Keith’s skull, and he limps. They have a Sealyham terrier called Sam Small.

Ray finds it hard to adjust to being a civilian again. The regal city of her birth is in ruins. The thrilling pace of her adult life has halted. She manages to get a job with the British Travel Association but after three dull years she gives it up and starts training to become a nurse. Ray is twenty-eight and all the other trainees are nineteen. They wear butterfly caps and long, striped dresses. They scrub floors, empty bedpans, dress wounds. Ray loves the warm glow of the ward at night – its radiantly white bed sheets against the dark blue of the sky through the naked windows.

During the holidays Ray visits her old friend Lana in Ireland. Lana lives with her family in Clydaville – a formidable country house by a river. Ray takes the boat to Dublin and Lana’s fiancé, Frank, picks her up at the port. Frank is tall and erudite and charming. During the lengthy dinners at Clydaville he seats himself opposite Ray and shoots sultry looks across the tablecloth beneath the gauzy light of the paraffin lamp. Then one day Lana meets a young medical student on the train, falls in love, and breaks off her engagement. The next time Ray arrives in Dublin port, Frank is waiting for her. He takes her to dinner. She laughs at the way he pronounces the word ‘butter’. He laughs at the way she pronounces the word ‘police’. Lana did not want him anyway.

Norah does not trust Frank, because he is Irish. And Frank’s mother does not trust Ray, because she is English, and a year older than him, and godless. Barbara thinks Frank is devastatingly handsome and Beryl warns Ray off good-looking men, but they get engaged anyway. Frank has Lana’s ring recast and Ray gives her notice to the hospital. Then she goes to the Catholic church in Blackheath to start her instruction. Ray likes the incense and the ritual. She finds that the scriptures make sense to her and the prayer fills a space in her life that she had not noticed. The wedding takes place in May, 1952. Ray wears a white satin dress handmade by Beryl. It has long sleeves and tens of tiny pearl buttons. Beryl is her bridesmaid and Barbara is her maid of honour and Anna, Barbara’s baby daughter, wears a fluffy angora bolero and carries a posy. Afterwards they have finger food in Norah’s garden. It’s a halcyon day and the pear tree is bursting with light. Ray exchanges her veil for a jaunty red hat with a black ribbon and sets off on her honeymoon. She is still a virgin on her wedding night.

Frank works as a businessman with the Irish Export Board. For the first year of their marriage he is stationed in Dublin and they live on the first floor of a Georgian terrace. Frank doesn’t have a bank account and keeps all of his money rolled up in a Chesterfield tobacco tin. He peels off £5 a week and gives it to Ray for the housekeeping. Ray is dreadfully homesick. She learns to cook. She goes to Mass every morning just for company. There is an artist who lives in the basement flat and on sunny afternoons Ray watches him for hours, working at his easel in the garden.

Ray falls pregnant and Frank gets posted to New York. They travel first class for five days on a luxury liner. It’s stormy and Ray experiences seasickness; watching Frank trying to swim lengths of the pool on the bottom deck, the water inside sloshing and slapping against the tiles with the heave of the water outside. They live in a duplex in Jamaica, Queens. Ray is impressed by the buildings in Manhattan but repulsed by the food. She gives birth to her first daughter, Deborah, in 1953. The doctor administers an anaesthetic, slices through her pelvic floor and yanks the baby out. Deborah is skinny and squally and Ray has no idea how to keep her alive. She is already thirty-two, an abnormally old mother. Her second baby is born in 1955. Ray spends two lonely years in New York and comes home with two daughters.

Frank’s next posting is London. Beryl is based on the Isle of Wight and Norah is living with her, and so Ray and her family move into the vacant house in Blackheath. Norah has added a little aviary to the garden, with goldfinches, redpolls and green budgerigars. She has stipulated that all three sisters will inherit the house but Beryl, the spinster, must be allowed to live in it for as long as she wishes. Ray is happy in London but after two years Frank is posted back to Dublin. Frank, as it turns out, has a superiority complex and a volatile temper. He is always the one to decide which plays and films they go to see. He tells Ray what books she should read and never asks for her opinion after she has finished. He sleeps with other women and when Ray finds out and threatens to leave him he starts to breathe strangely; he pretends that he is having a heart attack.

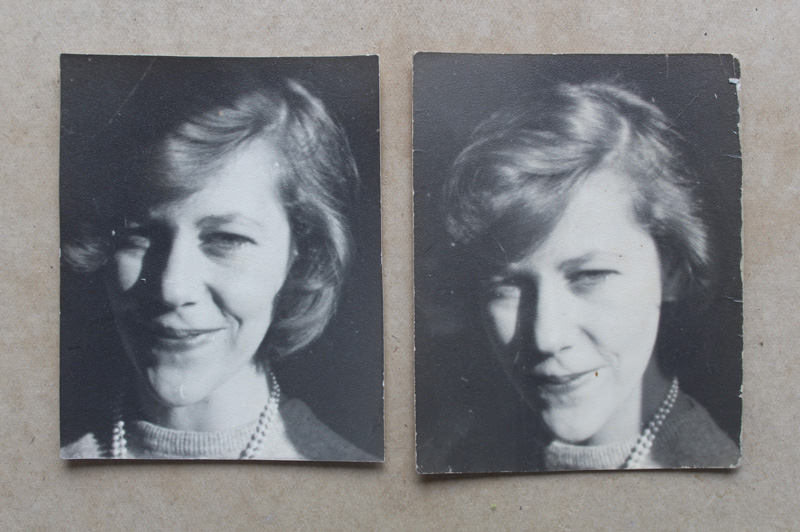

Ray, c. 1952

Back in Dublin Ray and Frank buy their first house and have their only son, and five years later, their final daughter. After her fourth child Ray has a problem with her fallopian tubes and the doctors decide to perform a hysterectomy. In her mid-forties Ray experiences an early menopause and just as she is getting better, Norah dies. Ray travels to London to be with her sisters. They talk about burying Norah in Chester with Reginald but it is too complicated, and so she is cremated, and because they cannot agree on a place to scatter her ashes they scatter Norah right there in the gardens of the crematorium.

Back in Ireland Frank becomes a chief executive and buys a holiday home for his family down on the south coast. The house has a rangy front lawn that runs down to a pebble beach and a pier that can be dived off at high tide. On the last day of the school term Ray packs up her Mini Cooper and straps four bicycles to the roof and waits outside the school gates for the final bell. Frank spends the weekends with his wife and the weekdays with his girlfriends in Dublin. Ray loves the sea. She establishes a rockery and a strawberry patch. The holiday home feels like a consolation for all the lonely years of marriage. She is there, sitting on a rug on the sea-facing lawn with a book and a battery radio, on the morning she hears that Lord Mountbatten and his wooden boat have been blown up by the IRA.

In the seventies Barbara and Keith open a second shop in Blackheath selling silk lingerie and French perfume. It’s the first boutique in London to stock G-strings. Barbara has become the glamorous sister. She wears fashionable clothes and paints her fingernails and has a sherry at lunchtime in the roof garden with Keith, who is now completely bald. Ray visits her sisters at least twice a year and at least once a year Beryl crosses on the boat to Ireland in her car, a tangerine MG Midget, with Prudence the sausage dog in the passenger seat. Prudence wears a diamond collar and has a skin condition that requires her to be dabbed with TCP. Sometimes Deborah visits London and stays with her spinster aunt in the large house with the rickety aviary. Beryl eats porridge for breakfast every morning but when her niece comes to stay she buys a variety pack and serves it with soft brown sugar in spite of the fact that she has always been disapproving of Ray’s children; because there are so many of them; because they are Irish. Beryl retires a decade before the WRNS are subsumed into a force that no longer separates the women from the men. She goes on cruises to far-flung places and has very long hair that she wears in a bun. Frank jokes that she will leave all her money either to the Conservative Party or the Battersea Dogs Home.

The holiday home, always draughty and creaky, has started to crumble by the early 1980s. Ray and Frank sell up and buy a house nearby in Ballycotton, with spiral stairs and a big concrete balcony and a view of a lighthouse. Ray swims in every season and walks the cliffs each morning with her dog. She has a dog called Gyp, then a dog called Voss, then a dog called Jack. She always chooses mutts. She goes to Mass. She plays tennis. She forms a painting group. They meet every week around the kitchen table if it’s raining, or out on the concrete balcony if it’s fine. Sometimes they set up their easels in the garden. They have an exhibition every July in the Cliff’s Stop Cafe.

Frank dies in Ballycotton in 1991. It’s January and he has just returned from a walk along the cliffs where he was hunting for early primroses. He collapses on the parquet floor of the kitchen and has a real heart attack. Ray and her children buy a double plot in the local graveyard and plant Frank there, with primroses on top. Keith dies three years later. Ray flies to Blackheath for the funeral and the sisters sit together in the roof garden and sift through black-and-white photographs, reminding each other of the colours they lack: the pink of Sam Small’s pendant tongue, the cheerless olive green of Keith’s Royal Engineers uniform, the gold of his hair.

The sisters are in their seventies now. Ray and Barbara are grandmothers. Ray has a prominent dowager’s hump. She wears tweed skirts and tracksuit jumpers and finally applies to go to university. She does a short course in Women’s Studies, then she starts a degree in English and History. She buys a laptop and learns how to use it. She graduates when she is eighty-four. All of her children attend the ceremony and take pictures of their mother in her gown and mortar board to send to Barbara. Ray doesn’t travel to London any more but she talks to her little sister every week on the phone and they exchange news of their big sister, who has grown even more cantankerous. Ray and Barbara try to convince Beryl to move out of the large house in Blackheath so that they can finally share their inheritance, but she will not budge.

Ray starts to research for her master’s degree. She gets up early every morning, walks her dog, goes to Mass and then to the city archives. Deborah and her granddaughters visit every Sunday for afternoon tea. They talk about novels over egg sandwiches and Fox’s Classic biscuits. Ray is happy. Her only remaining wish is that she will not lose her mind and be a burden on her family. In 2007, age eighty-six, she is diagnosed with oesophageal cancer and dies at home with all her children flanking her bed, keeping vigil. In her final hours Ray floats in and out of consciousness and dreams back through her life in brightly lit scenes. She sees her easel in the garden, a patch of ripe strawberries, the luminous pear tree. She sees the naked windows of the hospital ward, the stars between funnels above the Red Sea, the Zeppelins tethered to steel cables. She sees the sweeping strand at Birchington, the glistering water; she smells the salt and weed.

Death, like the bomb that never hit her, makes no sound. Ray chooses not to be buried alongside Frank, and so she is cremated, and Deborah donates the handwritten notes for her semi-completed thesis to the city archives.

Beryl has a hip operation and finally sells Norah’s house in Blackheath and moves into sheltered accommodation. On her final cruise she slips on deck and is airlifted to a hospital in Buenos Aires. She makes it home to England, reaches her ninety-second year and dies of a stroke. Her nieces and nephew are surprised to find that their spinster aunt had not been rich after all. In fact Beryl dies penniless after decades spent sponsoring children in the Horn of Africa through various charitable organisations. Nobody finds out what happened to Prudence’s diamond collar.

Barbara misses her sisters, but then she starts to forget. She forgets that Beryl and Ray have died. She forgets that they grew old. She forgets the present, and then the recent past, until all she remembers is the distant past. She remembers the G-strings and the toy shop. She remembers Anna in her angora bolero and Keith holding her hand in the ambulance. She remembers the gramophone in the dining room and the farm animals in all the pockets of her cardigan, and finally, she remembers the pearly white sides of her treasure cot, the lacy canopy and the trailing silk ribbons and the smiling face of her big sister, Ray, peering inside at her.

Feature artwork courtesy of the author, a found photograph