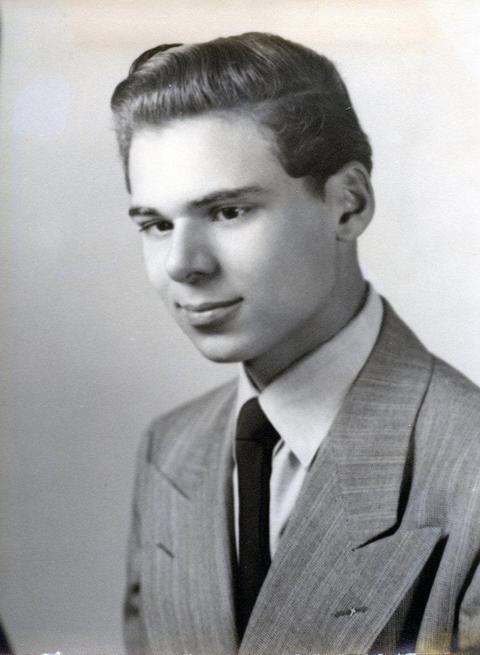

Here’s my father in 1947, wrapping up four undistinguished years at Fort Hamilton High School in Brooklyn. People who’ve met me since I became an adult may be surprised to learn that this is pretty much exactly the way I looked until I was about twenty years old, except that I didn’t wear a duck’s ass or a drape suit, or have the crossed eye (which my father later had surgically corrected) that you can’t quite see in this picture. Neither of us looked like this for very long, but the comparative effect lingers: those who strongly resemble one parent will recall the unsettling feeling of gazing into old photos and seeing, in relation to themselves, not the remote similarity of the grown-up sitting across the dinner table, but an exact likeness.

I find fascinating my father’s naked upper lip. After getting out of basic training in 1950 my father grew the moustache that he wore continuously until around 1994, when he shaved it off and then almost immediately grew it back again. Thank God he did – for my father to have shaved was as if he’d decided to have a go at life without a nose, or with a single eye planted in the middle of his forehead. The theme of my father’s face was that moustache. Whether it looked like Billy Eckstine’s or David Crosby’s, everything cohered around it.

It’s a sweet picture though, no? My father always struck me as a man with a skeptical, omnivorous awareness of everything (it was a brave pose, of course), but here he doesn’t know a thing. Here, the veil that obscures the abyss of the future is worn complacently. He’s not thinking about moving to Manhattan, or about becoming an artist, or even about Brooklyn College. He’s not thinking about the army, or about his first marriage. Not thinking about his mother’s death, or about being one of William Carlos Williams’ pallbearers, or about my sister, who died two years before he did. He’s not thinking about the Cedar Tavern, where he met my mother. Not thinking about paying child support. Not thinking about Penn Station, the South Bronx, or Bikini Atoll. He’s not thinking about editing Beckett and Malcolm X for Grove Press. He’s not thinking about spending twenty years teaching at Stanford, or about writing thirty books, or about spending forty years getting them and keeping them in print. Not thinking about James Joyce or William Faulkner or W.B. Yeats. He’s not thinking about rock and roll. Not thinking about Joseph McCarthy, Lee Harvey Oswald, Robert McNamara, Richard Nixon, or Ronald Reagan; or about Israel, Vietnam, or Watergate. Not thinking about JFK, RFK or MLK. He’s not thinking about terrorism or the internet. Not thinking about alcoholism, depression, stroke, congestive heart failure, leukemia, lupus, or lung cancer. He’s definitely not thinking about the Los Angeles Dodgers. He might be thinking about that cockeye of his, though. He was just about eighteen.