My father left school at thirteen; his family needed the money. When I asked him what he’d like me to say in this piece, he said,

‘Tell them I was in the Navy from 1942 to 1947, in four different invasions, in North Africa, France, Italy and I forget the other one. Tell them I’m eighty-four and a half. Tell them I’m a good salmon fisherman and so’s my daughter, who caught the third biggest fish of the year last month at Delphi in Ireland.’ No I didn’t, I said. It was the gillie. I just held the rod a bit. He laughed. ‘Aye, but don’t tell them that.’ My father put all five of us, my brothers and sisters and me, through university with a passion and foresight it took me decades to appreciate. My father is English. Whenever people in the Highlands, where he’s lived since he married my mother in 1949 (she died in 1990), comment on his Lincolnshire accent, he says, ‘I came up to work on the Hydro dams and never had the train fare back again.’ He was the main electrical contractor in Inverness and the Highlands in the Sixties and Seventies, until the coming of Thatcher, Dixons, Currys.

‘Tell them I’m still Conservative after all these years,’ he said. There’s no way I’m telling them that, I said.

My father, one afternoon, sat at the dinette table, unscrewed my talking bear whose cord had broken, and screwed it back together. It worked. ‘When people are dead, graves aren’t where to find them. They’re in the wind, the grass.’ That’s the kind of thing he said. When I asked him what you do if you see something in the dark that frightens you, he said, ‘What you do is, you go up to it, and touch it.’ When things went wrong in the neighbourhood, people would come to my father for help. When we went to visit an old neighbour last autumn, in her eighties too, she called him Mr Smith. ‘Call me Donald, now, Chrissie,’ he said. She shook her head. ‘You’ll have another biscuit with your tea, Mr Smith,’ she said.

My father, as a boy, was a champion footballer, boxer, ping-pong player. His handsomeness, as a young man, is legendary. Every time I left for university, he tucked twenty pounds and a folded sheet of stamps into my pocket. ‘Write to your mother,’ he said.

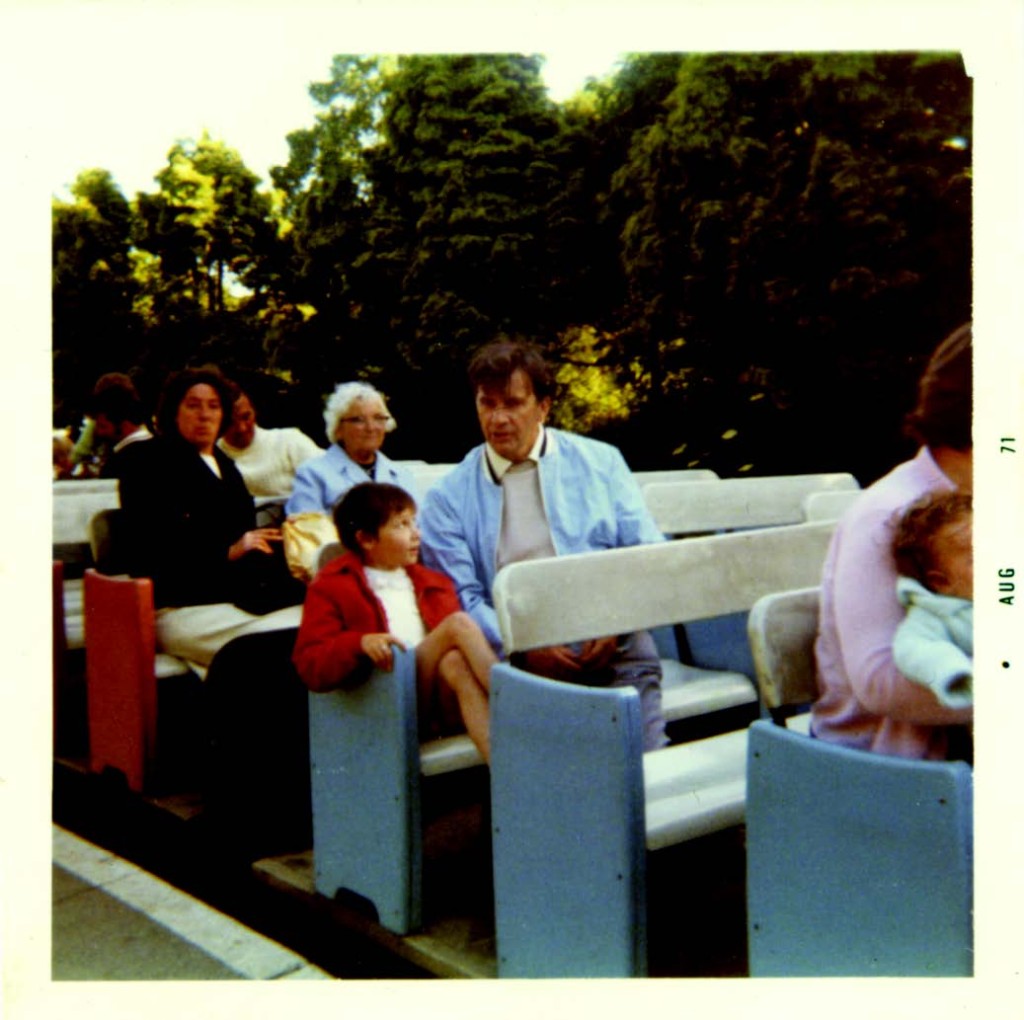

Ali and Donald Smith, 1971