In 1923 a group of women travelled from Surrey to establish themselves at the Tymawr Convent in Monmouth, Wales, to live a life of contemplation under monastic vows of poverty, chastity and obedience. The Society of the Sacred Cross celebrates its centenary this year. At the time of writing, eight sisters, from their mid-twenties to mid-nineties, remain at the Anglican convent, the only establishment of its kind in Wales. Among them are lawyers, nurses, academics, poets and painters. Some, who felt the call to devotion later in life, are both religious and literal mothers.

Tymawr, in the Wye Valley, is a largely self-sufficient community. The sisters’ lives revolve around labour as much as contemplation. They clean, cook and work in the convent’s expansive gardens and orchards (ecological sustainability is paramount in the community’s approach to cultivation – in the Society’s 2022 Advent Newsletter, the Reverend Mother Katharine writes with sadness of mankind’s ‘thankless misuse of the created world’). Alongside these duties there are five daily prayer services, including an hour-long midday mass. The sisters are also expected to spend two further hours in solitary, silent prayer. But perhaps it is wrong to separate the domiciliary and venerational strands of the sisters’ lives in this way. The two endeavours dovetail – work is worship, and worship work. They live as much of their lives as practically possible in silence.

If this all sounds rather ascetic to your secular ears, I should stress that the convent’s seclusion is far from anchorite in its rigour. The services are open to the local community and Tymawr often welcomes guests, including Suzie Howell, who in September 2022 spent six days photographing the sisters as part of her ongoing project on the theme of ‘presence’, a project prompted by her own struggles ‘living comfortably in the present’, finding contentment – perhaps even satisfaction – in stasis, or silence.

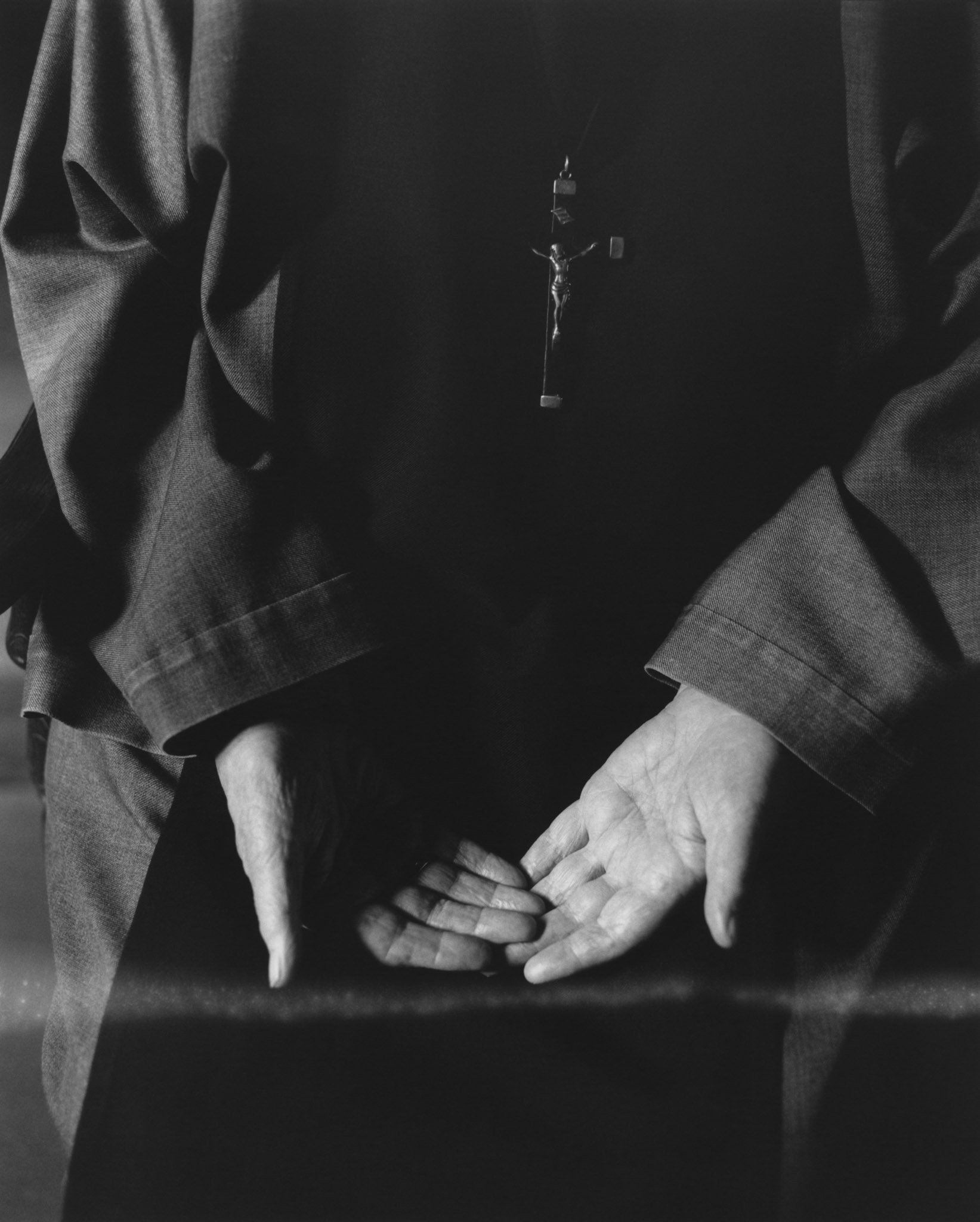

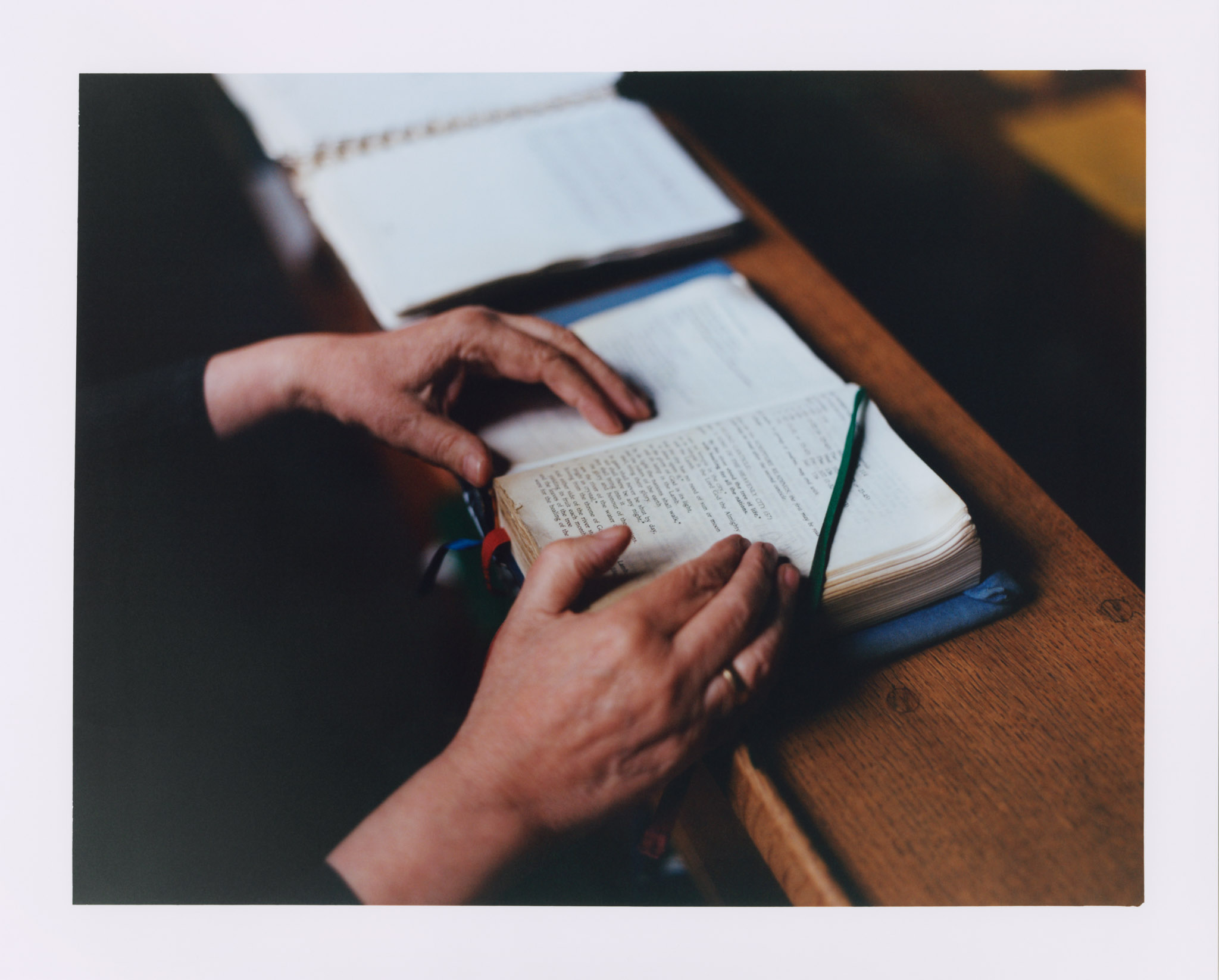

Like the voice, the hand is one of our primary means of interacting with the world around us, by which we might manipulate, move or change it. The hands of the sisters in Howell’s photographs do not appear active or manipulative in this way. Evoking devotional artworks, they are open, upraised or still. Postures of graceful receptivity, or surrender. How do we tell the difference?

These hand-pictures were the product of necessity rather than intention. Howell, who speaks passionately of her time among the sisters, describes how at first they were reluctant to be photographed at all: ‘There was no ego there. They didn’t want their faces shown or names used.’ Rather than be photographed in full, they offered up their hands.