The pain her son had caused her by choosing to die on a day in spring was less than she had expected. He is happy now, she said. And she herself felt almost relieved. She would have liked to die that way. Or she might have chosen a different method. But which? Pain let itself be pushed about like a paper kite and she, the mother, after having pondered the various ways of dying, was in absolute agreement with her only son, on the perfect choice. It couldn’t have been otherwise. She shut her eyes in order to see the scene, she knew the place by heart. Meanwhile she thought that she would have to change her will. The son had let himself fall off a rock, on the glorious Via Mala, where as a child they had taken him to see the gorges. Jörg looked unhappily at the water down below, lizard green, deep down. The mother dragged him way up, so as to have him look below. To force him to look down. His step faltered. He was sickly, wan. And this did not please the mother who held him by the hand. The boy looked at the emerald ring, the same colour as the water. Beyond the limits of the visible. And today, years later, he went down. No one forced him. Of his own will. His will pushed him to the end. Almost as though to recover his eyes as they’d been back then, that had settled with hatred on the pools of water. He hardly realised that he was going down, falling, the green water rocking him and the sharp edges of the rocks had already torn him apart. Fossil lances. He left the bicycle padlocked. Out of habit. He had been advised to ride a bike to attempt to calm his insomnia. You must tire yourself out. You must tire yourself out a great deal. With some physical exercise. The insomnia lessened. At the same time tiredness increased. The doctor is pleased. And the mother who had got him used to sleeping pills, too. They were a dynasty of insomniacs. Of insomniac women. The men were more given to sleep. They had always slept, the mother said on a sour note. Why then could her son not sleep? The tiredness had to be increased so that the insomnia could decrease. The only son had become so tired that he no longer cared about the insomnia. He didn’t even notice. He stayed up all night, it seemed to him that he had a great deal to do, in the doing of nothing.

Then, when he managed to stretch out on the bed, he had the sensation of entering sleep. He was entering, given his enormous tiredness, into a kind of eternal rest. It was something very beautiful. He had experienced something like that with opium. He was lying on a sofa, an uncomfortable nineteenth-century sofa. His feet were resting on the wooden armrest. He was waiting. A hedge blocked the window. While nothing happened between the eyelids and the eyes, his legs lengthened, almost as though to touch a distant, very distant line with the tips of his shoes. It was just the horizon. A curved line in the shape of a sickle. And the sickle had flattened and skimmed the waves of the sea. There was absolute stillness. An enamel landscape, innocuous, mute. And he, the boy, felt so well, in the shadowy peace. In the light malaise in the air. The flush of spring, the scent was nauseating, tainted and too strong. The solemn and glorious instant just before dissolution. In a field he saw flowers with small purple wounds. Tattooed flowers. A minuscule branding, such as is used on herds, or linens. Someone must have marked them as they went by. But who? He didn’t care. The flowers were coming back before his eyes, before his door. He had shut them out. When the vision faded, he saw the wall. He opened the door.

The mother was there, holding a tray. ‘I made you some dinner.’ Shellfish and something pink, boiled and grey, with two holes. His mother liked foods he couldn’t stand. Such as fish, for instance. No one could deceive him as to freshness. There are those who have an inborn gift for not being deceived in life. Neither by food gone bad nor by the Holy Ghost. She was pleased if the butcher gave her a beautiful cut of meat. And so, in the end, she was pleased with the death of her son. With the perfect choice. Understanding and charity begin in the mother’s womb. On the Via Mala.

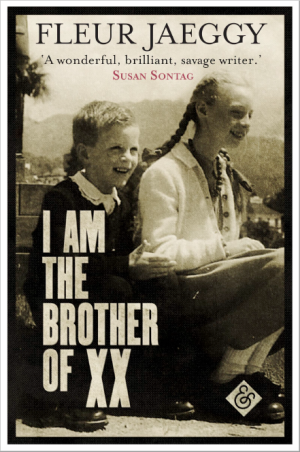

This is an excerpt from Fleur Jaeggy’s collection I Am the Brother of XX, translated from the Italian by Gini Alhadeff and published by And Other Stories.