When I arrived to spend a few days in the West in September 1968 – my eyes still seeing Russian tanks parked on Prague’s streets – an otherwise quite likeable young man asked me with unconcealed hostility: ‘So what is it you Czechs want exactly? Are you already weary of socialism? Would you have preferred our consumer society?’

Today, sixteen years on, the Western Left almost unanimously approves of the Prague Spring. But I’m not sure the misunderstanding has been clarified entirely.

Western intellectuals, with their proverbial self-centredness, often take an interest in events not in order to know them but so as to incorporate them into their own theoretical speculations, as if they were adding another pebble to their personal mosaic. In that way Alexander Dubček may in some circumstances merge with Allende or Trotsky, in others with Lumumba or Che Guevara. The Prague Spring has been accepted, labelled – but remains unknown.

I want to stress above all else this obvious fact: the Prague Spring was not a sudden revolutionary explosion ending the dark years of Stalinism. Its way had been paved by a long and intense process of liberalization developing throughout the 1960s. It’s possible it all began even earlier, perhaps as early as 1956 or even 1948 – from the birth of the Stalinist regime in Czechoslovakia, out of the critical spirit which deconstructed the regime’s dogma little by little, pitting Marx against Marxism, common sense against ideological intoxication, humanist sophism against inhuman sophistry, and which, by dint of laughing at the system, brought the system to be ashamed of itself: a critical spirit supported by a crushing majority of the people, slowly and irremediably making power aware of its guilt, less and less able to believe in itself or in its legitimacy.

In Prague we used to say cynically that the ideal political regime was a decomposing dictatorship, where the machine of oppression functions more and more imperfectly, but by its mere existence maintains the nation’s spirit in maximum creative tension. That’s what the 1960s were, a decomposing dictatorship. 1 When I look back, I can see us permanently dissatisfied and in protest, but at the same time full of optimism. We were sure that the nation’s cultural traditions (its scepticism, its sense of reality, its deeply rooted incredulity) were stronger than the eastern political system imported from abroad, and that they would in the end overcome it. We were the optimists of scepticism: we believed in its subversive force and eventual victory.

In the summer of 1967, after the explosive Writers’ Congress, the State bosses reckoned that the decomposition of the dictatorship had gone too far and tried to impose a hardline policy. But they could not succeed. The process of decomposition had already reached a guilt-ridden central committee: it rejected the proposed hardening of the line and decided to be chaired by an unknown newcomer, Dubček. What’s called the Prague Spring had begun. The critical spirit which up to then had only corroded, now exploded: Czechoslovakia rejected the style of living imported from Russia, censorship vanished, the frontiers opened and all social organizations (trade unions and other associations) intended to transmit meekly the Party’s will to the people, became independent and turned into the unexpected instruments of an unexpected democracy. Thus was born (without any guiding plan) a truly unprecedented system – an economy 100 per cent nationalized, an agriculture run through cooperatives, a relatively egalitarian, classless society without rich or poor and without the idiocies of mercantilism, but possessing also freedom of expression, a pluralism of attitudes and a very dynamic cultural life which powered all this movement. (This exceptional influence of culture – of literature, theatre and the periodical press – gives the sixties as a whole its own special, and irresistably attractive, character.) I do not know how viable the system was or what prospects it had; but I do know that in the brief moment of its existence it was a joy to be alive.

Since the Western Left of today defines its goal as socialism in freedom, it is logical that the Prague Spring should henceforth figure in its political discourse. I note more and more often, for example, comparisons between the Prague Spring and the events of May 1968 in Paris, as if the two had been similar or moving in the same direction.

However, the truth is not so simple. I won’t speak of the almost too obvious difference in scope between the two (in Prague we had eight months of an entirely original political system, and its destruction in August was a tragic turn in our nation’s history), nor will I descend into ‘politological’ speculations which bore me and, worse still, are repugnant to me, for I spent twenty years of my life in a country whose official doctrine was able only to reduce any and every human problem to a mere reflection of politics. (This doctrinaire passion for reducing man is the evil which anyone who comes from ‘over there’ has learned to hate the most.) All I want to do is to put my finger on a few reasons (without masking their hypothetical nature) which show that despite the common non-conformism and the common desire for change, there was a substantial difference in the climate of the two Springs.

May ’68 was a revolt of youth. The initiative in the Prague Spring lay in the hands of adults who based their action on historical experience and disillusionment. Of course youth played an important role in the Prague Spring, but it was not a predominant role. To claim the opposite is to subscribe to a myth fabricated a posteriori on order to annex the Prague Spring to the epidemic of student revolts around the world.

May in Paris was an explosion of revolutionary lyricism. The Prague Spring was the explosion of post-revolutionary scepticism. That’s why the Parisian students looked towards Prague with mistrust (or rather, with indifference), and the man in Prague could only smile at Parisian illusions which (rightly or wrongly) he thought discredited, comic or dangerous. (There is a paradox worth meditating upon: the only successful – if ephemeral – implementation of socialism in freedom was not achieved in revolutionary enthusiasm but in sceptical lucidity.)

Paris in May was radical. What had paved the way over many years for the Prague Spring was a popular revolt of the moderate. Just as Ivana the Terrible, in Škvorecký’s Miracle in Bohemia, replaces ‘bad quotations from Marx with less bad ones’, so everyone in 1968 sought to blunt, soften, and lighten the weight of the existing political system. The term thaw, sometimes used to refer to this process, is very significant: it was a matter of making the ice melt, of softening what was hard. If I speak of moderation, it’s not in any precise political sense, but in the sense of a deeply rooted human reflex. There was a national allergy to radicalism as such, and of whatever kind, for it was connected in most Czechs’ subconscious minds to their worst memories.

Paris in May ’68 challenged what is called European culture and its traditional values. The Prague Spring was a passionate defence of the European cultural tradition in the widest and most broad-minded sense – as much a defence of Christianity as of modern art, both equally denied by the authorities. We all struggled for our right to this tradition, threatened by the anti-Western messianism of Russian totalitarianism.

May in Paris was a revolt of the Left. As for the Prague Spring, the traditional concepts of right and left are not able to account for it. (The left/right division still has a very real meaning in the life of Western peoples. On the stage of world politics, however, it no longer has much significance. Is totalitarianism left-wing or right-wing? Progressive or reactionary? These questions are meaningless. Russian totalitarianism is above all else a different culture – and therefore also a different political culture – in which the European distinction between those of the left and those of the right loses all sense. Was Khrushchev more left or more right than Stalin? The Czech citizen is confronted today neither by left-wing terror nor by right-wing terror but by a new totalitarian culture which is foreign to him. If some of us think of ourselves as more right-wing or more left-wing, it is only in the context of the West’s problems that we can conceive the distinction, and not at all with reference to the problems of our country, which are already of a different order.)

All this created a spiritual atmosphere rather different from the one familiar to opponents west of the Elbe, and Josef Škvorecký represents this atmosphere better than anyone else.

He entered literature with The Cowards, an exceptionally mature novel written just after the war, when he was a mere boy of twenty-four. The book stayed in a bottom drawer for many years and was not published until the brief thaw which followed the year of 1956 – unleashing an immediate and violent ideological campaign against the author. In the press and in many meetings, Škvorecký had the very worst epithets flung at him (the most famous was ‘mangy kitten’) and his book was banned from sale. He had to wait until the sixties and another thaw to be republished in an edition of a hundred thousand copies and to become not only the first big bestseller of the post-war literary generation in Czechoslovakia but also the very symbol of a free and anti-official literature.

But why in fact was there a scandal? The Cowards does not denounce Stalinism or the Gulag and does not fit what the West calls dissident writing. It tells a very simple story of a young schoolboy who plays in an amateur jazz band and tries his not always lucky hand with classmates of the opposite sex. The story is set in the last days of the war and the young hero watches the spectacle of Liberation in all its derisory unworthiness. It’s exactly that aspect which was so unseemly: a non-ideological discourse dealing with sacred subjects (the Liberation is now enshrined in the gilded showcases of all European museums) without the seriousness and respectfulness which is obligatory.

I have dwelt at some length on Škvorecký’s first book because the author is already fully present in it, some twenty-five years before this Miracle was written in Canada: in both we find his special way of viewing history from underneath. It’s a naively plebeian view. The humour is coarse, in the tradition of Jaroslav Hašek. There’s an extraordinary gift for anecdote, and a mistrust of ideology and the myths of history. Little inclination for the preciousness of modernist prose, a simplicity verging on the provocative, in spite of a very refined literary culture. And finally – if I may say so – an anti-revolutionary spirit.

I hasten to gloss this term: Škvorecký is not a reactionary and he would no doubt not have wished for the return of nationalized factories to their owners or for the dissolution of farm co-operatives. If I mention an anti-revolutionary spirit in connection with him, it is to say that his work represents a critique of the spirit of revolution with its myths, its eschatology and its ‘all or nothing’ attitude. This critique does not touch on any concrete revolutionary demands or policies, but concerns the revolutionary attitude in general as one of the basic attitudes which man can adopt towards the world.

The Western reader can only be surprised. What can one expect from a Czech writer who emigrated after the 1968 invasion except that he should write a defence of the Prague Spring? But no, he hasn’t done that. It’s precisely because Škvorecký is a child of his country, faithful to the spirit whence issued the Prague Spring, that he writes with unwavering irony. What strikes the eye first is his critique (through anecdote more than through argument) of all those revolutionary illusions and gesticulations which tended as time went by to take the stage of the Prague Spring.

In its originating milieu, Škvorecký’s view of the Prague Spring has already provoked violent polemics. In Bohemia, his novel is not just banned (as are all the writer’s other works) but it is also criticized by many who hold the current regime in contempt, for whom (understandably enough) ironic distance is not possible when they look at themselves in the tragic and difficult circumstances in which they live. Each of us is free to enter into a polemic with this novel, but on one condition: without forgetting that Škvorecký’s book is the fruit of a rich experience, in the best realist tradition.

All that is to be read here carries the stamp of truth and contains many accurate renderings of real people and events; this applies also to the main plot – a ‘miracle’ set up by the police who manage thereby to convict a priest of fraud and to invent a pretext for a violent anti-religious campaign; only the real name of the village, Ĉihoŝt, has been changed to Písečnice. Ivana the Terrible, the headmistress who picked out the least bad quotations from Marx, is a real heroine of moderation: I knew dozens of her sort. She struggles patiently, silently, against one kind of radicalism, only to fall prey in the end to an opposite kind. (Incidentally, I doubt whether any Communist writer has ever managed to create a more moving Communist than Škvorecký – a convinced non-Communist – gives us here.) The poet Vrchcoláb, the playwright Hejl, the chessmaster Bukavec are portraits of real, known, living persons. I don’t know whether that’s also the case for the Russian writer Arachidov, but whether or not he has a model in reality he seems more real to me than reality itself. And if you suspect Škvorecký of exaggeration, I can assure you that reality exaggerated much more than Škvorecký. Though all these portraits are marvellously malicious, the novel’s hero Smiřický (a kind of stylized self-portrait of the author), who calmly writes an official speech for Lenin’s birthday without believing a single word of what he sets down, by no means represents the Truth nor does he constitute a ‘positive’ hero, even if he is presented in a sympathetic light. Škvorecký spares him little of the tide of irony which inundates the entire novel. This book is until further notice the only work to give an overview of the whole implausible story of the Prague Spring, while at the same time being impregnated with that sceptical resistance – in its most authentic form – which is the best card in the Czech hand.

The fire which Jan Palach lit with his own body in January 1969 to protest against the fate which had befallen his land (his desperate act, it seems to me, is as foreign to Czech history as the ghostly sight of Russian tanks) – that fire brought a period of history to a close. Is what I said earlier on the spirit of the Prague Spring even very true? Can one still speak today of a revolt of the moderates? The Russian invasion was too terrible by far. Even the authorities, moreover, are not what they used to be in Bohemia. They are no longer fanatical (as in the 1950s) nor guilt-ridden (as in the 1960s) but openly cynical. Can plebian cynicism fight authority more cynical than itself? The time has come when the cynic Škvorecký no longer has a place in his own land.

1 Despite official ideology, there was an extraordinary flowering of Czech culture in these years. The films of Miloš Forman, Jiri Menzel, Vera Chytilova, the theatrical productions of Otomar Krajča and of the brilliant Alfred Radok, the plays of the young Václav Havel, the novels of Josef Škvorecký and Bohumil Hrabal, the poetry of Jan Skacel and the philosophical works of Jan Patocka and Karel Kosik all date from the 1960s. European culture has known in our country few better or more dynamic decades than the Czech sixties and their importance is the yardstick by which the tragedy of 21 August 1968, which killed them brutally, must be measured.

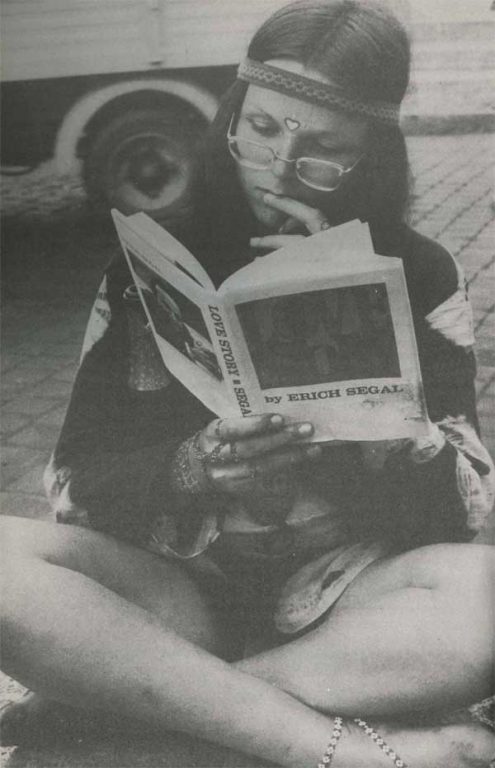

Featured photograph by Roman Boed; in-text photograph by Keystone