The following is an excerpt from The Ten Loves of Mr Nishino by Hiromi Kawakami, translated from the Japanese by Allison Markin Powell. A series of encounters with elusive womaniser Mr Nishino bring torments, desires and delights. The Ten Loves of Mr Nishino is available now from Granta Books.

Minami was seven years old back then.

She was a shy child. Always folding origami with her thin fingers. Morning glories. An organ. Parakeets. A little offering stand. She made all kinds of things, and then quietly put them away in a box covered with gaily patterned Chiyogami craft paper. I had been quite young when Minami was born.

When Minami was seven, I was still in my twenties, and sometimes I disliked her. My heart would ache after these unpleasant feelings, and I would hug Minami all the more tightly. It might have been my youth, coupled with the fact that Minami was still as tender and defenseless as a baby, which invited my dislike. Whenever I held Minami tight, she would always be very quiet and still. Minami didn’t say much when she was little.

I was in love back then.

Just what is love anyway? The person I was in love with was named Nishino – he was a full twelve years older. I slept with Nishino many times.

The first time Nishino put his arms around me, I silently let him hold me, the same way as Minami did with me. I just let him hold me, without wondering whether it was love or passion or whatever. Each time I saw Nishino, I would nestle in closer to him, but for Nishino, the feeling was always the same, no matter what.

What is love, really? People have the right to fall in love, but not the right to be loved. I fell in love with Nishino, but that’s not to say that he was then required to fall in love with me. I knew this, but what was so painful was that my feelings for Nishino had no effect on his feelings for me. Despite this pain, I longed for Nishino more and more.

*

Nishino called the house once while my husband was home. My husband didn’t say a word, he just handed me the receiver. Then he murmured, ‘Someone from an insurance company.’

Taking the phone from my husband, I whispered succinct responses into the mouthpiece: ‘Yes.’ ‘Right.’ ‘No.’ ‘Very well then.’ I listened to Nishino’s voice on the other end of the line, with him pretending to speak in the tone of an insurance salesman, adding deliberate pauses as he said things like, ‘I want to make love to you right now,’ while I thought to myself, ‘I might not even like this person, really.’

My husband was at my side, quietly looking over some paperwork, when I took this call from Nishino. My husband may have known everything or nothing at all. During the three years or so from the time I first met Nishino and fell in love with him, to when he gradually began keeping his distance, to when finally even the phone calls stopped, my husband never asked me any questions.

Staring at the tidy nape of my husband’s neck, I repeated the same words: ‘Yes.’ ‘Right.’ ‘I see.’ Nishino chatted for a few minutes and then abruptly hung up. Nishino was always the one to end our calls. I may not have liked him, but I had been in love with Nishino.

*

Sometimes Minami came with me to see Nishino. He would request that I bring her along.

‘Little girls are great,’ he often said. Nishino was unmarried. He must have already been in his forties at that time. Even though he was seven years older than my husband, Nishino had none of the slightly detached, self-possession of my spouse. Nishino always seemed uncomfortable around people, although he was apparently quite capable at his job – I remember being surprised, when we first met, by the impressive title on the business card he handed me.

Nishino would always have a small gift for Minami. ‘Just open it,’ Nishino would prompt her, and Minami would unwrap the package, without a word. The paper rustled as her slender fingers untied the red ribbon.

A delicate calligraphy brush stand encrusted with pink shells. A paperweight in the shape of a dog. A bean-paste bun sprinkled with poppy seeds. A music box no bigger than the palm of her hand. Minami gazed at these gifts, her expression barely registering any change, and then with a slight bow she would say softly, ‘Thank you.’

From the beginning, Minami never asked anything about Nishino. She simply held my hand, quiet at my side like a shadow. Should I have worried that Minami would say something about Nishino to my husband? Did a part of me hope that she might accidentally let it slip to him?

*

When Minami came along with me, Nishino and I had no physical contact. Instead, we would go to a restaurant that had a terrace, and before Minami could say a word he would order her a strawberry parfait, and hot coffee for himself and me. If strawberries weren’t in season, he ordered banana parfait.

‘Chocolate parfait is no good!’ Nishino declared, drawing out the last syllable of ‘parfait,’ so that it sounded like ‘par-fay-ee.’ Minami nodded vaguely, as did I.

As we nodded, I stole a glance at Minami, who was looking my way. Within the pale whites of her eyes, her pupils were starkly round and fixed on me. I raised my eyebrows slightly, and Minami smiled faintly, her brow lifting as well.

Minami never finished her parfait. And yet Nishino ordered strawberry or banana parfait every time.

‘Minami, dear, gets a par-fay-ee, right?’ he said, a note slightly higher than usual creeping into his voice as he peered at Minami’s downcast face.

After we left the restaurant, the three of us would always make two trips around the path through the park. Then we’d head to the train station, where we’d part at the ticket gate. Nishino bought tickets for us. He would place each of them in our hand – an adult ticket for me and a child ticket for Minami.

Once our tickets were punched, I’d turn back to see Nishino grinning and waving at us from the other side of the ticket gate. Minami never looked back, she just headed straight for the stairs in front of us. Nishino still waved at Minami, who clearly made no motion to turn around. Nishino waved at me, he waved at Minami, and he waved at the space in between us.

*

‘Mr Nishino was a strange guy, wasn’t he, Mom?’ Minami said this to me the spring she turned fifteen.

The last time I saw Nishino, it had been winter. Minami was still ten years old that season when he and I broke up. At the time, I hadn’t explained to Minami that Nishino and I wouldn’t be seeing each other any more, and she hadn’t mentioned him at all since then.

Now that I thought about it, while I was still involved with Nishino, there had been a few times when Minami actually laughed out loud in his presence. Once she realized that I was staring at her as she laughed, she stopped, seemingly self-conscious. And then she had sneezed softly several times.

By that spring, when Minami turned fifteen, I hardly ever thought about Nishino anymore. The sound of Nishino’s name suddenly emitting from Minami’s lips triggered a range of emotions within me. It felt as though a hole had been pricked in my belly and air was now leaking out.

*

‘Mom, you and Mr Nishino were lovers, weren’t you?’ Minami asked, looking me straight in the eye.

I thought about it, but I no longer knew. Even when Nishino and I had been seeing each other frequently, I hadn’t been sure. I no longer knew whether Nishino and I had been in love, or whether I had really liked him, or even whether or not someone named Nishino had actually existed.

‘When he called me ‘Minami, dear,’ it felt as if the palm of my hand had thick paint on it that I couldn’t wash off, no matter how hard I tried,’ Minami murmured softly, like she was singing.

For the past year or so, Minami had been going through a growth spurt. Her arms and legs kept getting longer and longer. Minami seemed made up of entirely new cells – her metabolism was so high, it was as if every few days the cells in her body were replaced completely.

‘The problem with Mr Nishino was, after seeing him, there was always some trace that seemed to linger.’

‘A trace?’

‘A sort of melancholy trace of something, almost bittersweet.’

‘Minami, why don’t we go get a par-fay-ee, for old time’s sake?’ I suggested, imitating the way that Nishino used to draw out the last syllable.

Minami laughed. ‘I wonder how Mr Nishino’s doing.’

‘I’m sure he’s just fine.’

‘I love the dog paperweight.’

Long after Nishino and I broke up, Minami still cherished the silver dog paperweight that Nishino had given her. She had named him Koro, and every so often she gave him a good shine with polishing sand.

‘And the bean-paste bun with poppy seeds, that was delicious.’

Nishino had a knack for giving gifts. To me too, though he had only given me a present once. A small silver bell. Dangling from my hand, it produced a clear ring.

From now on, I want you to wear it, Nishino had said with a smile. Then I’ll always know where you are, Natsumi.

And once you know, what will you do? I must have said. Will you run away, like the mice who belled the cat?

No, it’s so that I can catch you, Natsumi – so you won’t run away. As long as I know your whereabouts, then you can’t leave me.

Nishino’s words had made me blush a little.

*

The next time I saw Nishino, I wore the bell on a chain around my wrist. While Nishino made love to me, the bell tinkled faintly the entire time. I’m not letting you go, Nishino said.

I wonder what happened to that little bell. When I think of Nishino’s embrace, I am struck with a fleeting wistfulness, but I cannot quite recall the way in which I had been in love with him.

I told Minami, ‘Nishino said that when you grow up he’d like to go on a date with you.’

‘Very funny!’ Minami cried out.

‘That’s the kind of guy he was.’

‘A perv, you mean?’

‘He was just overindulged.’

‘He was ridiculous.’ But Minami’s voice was tender when she said this. She may not even have noticed the sweetness in her voice.

‘Minami, is there someone you like?’

‘Nope,’ she answered reflexively and stood up. An expression of denial on her face, with long strides she took the stairs, two at a time, and slammed the door to her room.

I wondered what Nishino had seemed like to Minami back then. As she had ascended the stairs, Minami’s body had emitted that saccharine scent that was particular to a girl her age. For the first time in a while, I had the urge to hear Nishino’s voice. This feeling that the fifteen-year-old Minami had evoked in me was different from the dislike she had aroused when she was seven years old, but it was still unpleasant.

*

Minami is now twenty-five.

She must have had a number of romances. Yet Minami has never said a word about any of them to me. Just as, when she was little, she quietly went about folding her origami, she must have quietly fallen in and out of love.

It’s been fifteen years or so since Nishino and I broke up. And it’s only now, after all this time has passed, that I’ve finally been able to clearly remember Nishino.

These days – quite often – I am struck by a memory of his voice or his body, or of something he said. As often as with someone who is right there. It happens so frequently, it’s occurred to me that Nishino might not even be around anymore.

Come to think of it, ‘When I die’ was the kind of thing Nishino would just come out and say. He would say it with a slightly indulgent tone. Sometimes I’m surprised when I realize that Minami is now practically the same age I was when I was seeing Nishino.

Long ago, Nishino would occasionally say, ‘The truth is, I want to get married.’

I would reply, ‘If you want to, why don’t you?’

‘Would you marry me, Natsumi?’ Nishino asked.

Knowing that he wasn’t serious, I would always shake my head.

‘C’mon, you’re no fun!’ Nishino would say cheerily, and I would feel a tightening in my chest. I pretended not to notice, but back when I was seeing Nishino, the shadows of plenty of other women were always lurking. This was what enabled him to speak so cruelly of marriage to me.

‘Hey, Natsumi, when I die, I’ll come to you,’ he once said.

‘What?’

‘When I die, I want to be by your side.’

‘I bet you say that to all the girls,’ I replied flippantly.

With an unusually serious look, Nishino said, ‘I don’t.’

*

‘Mom, someone’s in the garden,’ Minami called out.

Today was Friday, but Minami had taken a vacation day and had been at the house since the morning. Every so often, Minami would take off from work, for no reason. What’s the matter, I would ask, and she would simply smile at me, without saying a word.

I had a hunch it was Nishino.

I had just started to simmer some pumpkin, and the aroma of the mildly sweet stock wafted throughout the kitchen. The old refrigerator hummed noisily.

I stayed where I was, standing in front of the sink. ‘Minami, see who it is,’ I said.

The louver door to the garden opened. A moment later, I heard the clatter of wooden sandals on the paving stones. Soon the sound of her steps stopped. A gust of wind came up, and the grass rustled.

Then all the sounds ceased.

‘Mom, come here,’ Minami called from the garden.

Just as Minami’s voice had rung out, the refrigerator had started humming again.

‘I’m not coming out,’ I replied slowly through the kitchen window.

I looked out at the garden through the window lattice.

The shape of someone who seemed like Nishino was sitting in the dense weeds.

The surroundings beyond this shadow were clearly visible. He was sitting amid the thick grass, almost blending in with them. Minami was squatting, as she peered into the face of whoever this was.

He was sitting upright and tall. When Nishino was alive, he had been a bit more restless. He always seemed as though he wasn’t quite used to the air around him – he would be blinking his eyes or brushing back his hair.

‘Water . . .’ Minami was asking. ‘Would you like some?’

The shadow nodded slightly.

Even though Minami and Nishino’s shadow were some distance from me in the kitchen, somehow I could clearly make out both of their movements.

I turned on the faucet and filled a delicate glass with water. Then I made my way as far as the louver door, being careful as I walked not to spill the full glass of water.

Minami was waiting there for me, standing on the paving stone.

*

‘What is that?’ Minami asked.

‘Don’t you know?’ I replied in a low voice.

‘Is it Mr Nishino?’

‘It must be.’

‘Is he dead?’

‘Yes, probably.’

Minami and I looked at each other calmly. The wind chimes jingled. Amid the grass, Nishino stirred.

‘Is it alright if you’re not the one to give it to him?’ Minami asked as she took the glass of water from me.

‘I’d like you to give it to him for me.’

‘But . . .’

‘You give it to him.’

Minami pursed her lips, turning down the corners of her mouth, and with a sort of reckless gait walked back to where Nishino was. The water in the glass formed ripples, spilling over a bit. She passed the glass to Nishino and squatted beside him. Nishino accepted the glass politely with both hands and carefully drank all of the water.

‘He’d like more.’ As she handed me the empty glass, Minami seemed to be glaring at me. ‘Mom, why don’t you bring it to him?’

Small dragonflies were flitting through the grass. They darted among the foxtails and smartweed. Nishino sat there, looking in my direction. His mouth was moving but I couldn’t hear what he was saying. I went to the kitchen to fill the glass again.

‘Mom, why is Mr Nishino here?’ Minami asked. I remained silent, and just shook my head.

After draining the second glass of water, Nishino lay down on the ground. Minami took an old deck chair out of the shed and set it next to Nishino, kicking off her sandals as she sat down. Occasionally she and Nishino would exchange a few words.

‘I asked him why he’s here, but he doesn’t answer.’ Minami said from the deck chair with a sigh, turning her head toward me.

‘He told me he would come,’ I replied lightly, sitting on the veranda.

Nishino’s eyes were closed as he lay there, and he was humming. The longing that I used to feel for him came back to me vividly. Nishino had a lot of grey hair at his temples, and there were wrinkles around his eyes and mouth. It was the face of a man long past fifty.

‘Nishino,’ I called out for the first time.

Nishino kept humming. It sounded like the folk song, ‘Song of the Seashore.’ Next to him, Minami chanted, ‘If I wandered along the seashore tomorrow –’

From the veranda where I sat, I joined in softly.

If I wandered along the seashore tomorrow, I would remember things from long ago.

‘Nishino, this song is a little too appropriate for you,’ I called out, this time trying to sound as cheerful as possible. Nishino sat up slowly. He-heh-heh, he chuckled.

‘Natsumi, I’m here,’ Nishino spoke in a clear voice as he beckoned me.

‘Yes, here you are,’ I said, ignoring his gesture and standing up in the spot where I was.

‘I promised. Because I promised you, Natsumi, didn’t I?’

Nishino sounded just like himself. His voice had that distinctive, slightly indulgent tone.

Minami wore an expression of astonishment as she sat in the deck chair, hugging her knees.

‘Did you ever have a daughter?’ I asked from afar.

‘I never married.’

There were plenty of dragonflies and butterflies darting about now. Some of them even alighted on Minami’s shoulders or arms. A light breeze stirred the wind chimes.

‘Minami, dear, you’re so pretty now,’ Nishino’s eyes squinted with affection. ‘I wasn’t able to fulfill my promise to take you out on a date.’

‘I never made that promise!’ Minami pouted her lips.

‘I wouldn’t have taken you out for a par-fay-ee, it would have been a more grown-up date.’ As always, he drew out the word par-fay-ee.

‘Mr Nishino, I never liked parfait,’ Minami said mischievously.

‘I knew that.’ Nishino reached out a hand and gently patted Minami’s bare arm. The dragonflies and butterflies that had alighted on her all dispersed at once.

‘Nishino.’ I called out his name softly, and he sat up straight again, holding his hand out toward me.

‘Come, Natsumi.’ He looked at me with puppy-dog eyes.

‘No, I’m fine here. I don’t need to come over to where you are,’ I replied quietly.

‘Come here, Natsumi. I’m lonely.’

‘I’m lonely too.’

‘Minami, dear, you don’t look like your mother. You’re very pretty, Minami, dear, but your mother, Natsumi, is a beauty,’ Nishino said, his tone shifting.

That was just like Nishino. Minami laughed to herself. I have my father’s eyes, my mother’s nose, and my grandma’s mouth, Minami recited in a murmur.

*

Mom, stop wasting time over there and come here – no doubt Mr Nishino will be gone soon enough. The lush hydrangea leaves seemed to rustle in concert with Minami’s voice. Barefoot, I stepped into the garden. Pebbles stuck to the soles of my feet. The berries on the wild grasses grazed my calves.

‘Is your husband well?’ Nishino asked, sitting with his heels tucked neatly under him.

‘Every day is peaceful and quiet.’

‘What more can one ask for?’ As Nishino spoke these words, Minami sneezed. He comes all the way here after he died and the two of you are making small talk? she said as she continued to sneeze three times in a row.

‘Thank you for coming,’ I said as I approached Nishino, and rubbed my cheek against his.

‘A promise is a promise!’

‘I didn’t know you were so conscientious.’

‘Not when it comes to my body, but always when it comes to my heart.’

‘You haven’t changed a bit, have you? I said, pecking him on the cheek. Nishino looked as if he might cry, but he didn’t.

‘I’d like to be buried in this garden,’ Nishino said sincerely.

‘No way,’ Minami murmured with a smile.

‘She’s right – no way,’ I agreed.

That’s enough, Nishino, I said inside my head. I’m just happy you’re here.

‘Well, then, at least make me a grave.’ Nishino’s tone sounded just like when he used to order a parfait, all those years ago.

‘A grave?’ Minami retorted with surprise.

‘Like one for a goldfish, that would be nice.’

I looked at Nishino’s face. His expression was the one he often wore when he was alive, like that of a child being scolded by his mother.

‘Alright,’ I replied, and Nishino took me gently in his arms.

*

Nishino stayed in the garden until just before the sun set.

I went back to the kitchen and fried up dinner. Minami remained by Nishino’s side the whole time. As I was disposing of the cooking oil, I heard Minami cry out.

He must have left, I thought.

A moment later Minami appeared in the kitchen, her gaze fixed on the floor as she murmured, ‘He’s gone.’

Yes, he’s gone, I said to myself. I searched for a set of pincers in the back of a drawer. I pulled out a big wooden box filled with smaller boxes of somen noodles, selected one of the smaller boxes, and used the pincers to remove the nails at the four corners. I took apart the box and set the smallest rectangular plank on the counter. I went to get the calligraphy set that Minami had used in middle school, and on top of the counter I ground the ink, then with a thick brush I wrote out, ‘Here lies Nishino.’

I went out into the garden and. beside the graves of our goldfish and cat, I thrust the plank into the ground.

Back then, I really did love you, Nishino, I said like a prayer, my palms held together as I crouched before the grave. Minami squatted next to me.

We remained still, our eyes closed and hands in prayer. Then we both looked at each other.

Sometime, let’s go out for a par-fay-ee, I said to Minami as I stood up slowly. Minami nodded, without a word.

The dragonflies and the butterflies had also left the garden. Far in the distance, I could hear the tinkling of a bell.

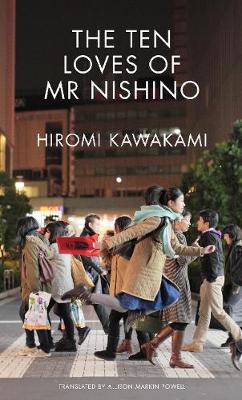

Image © papadont

The Ten Loves of Mr Nishino is available now from Granta Books.