One of my favourite pieces of editorial feedback received while I was writing Violets, my first novel, was, ‘I wonder if we need quite so much description of ironing..?’

We didn’t, but it was important that ironing was in there. Specifically, the ironing of intimate pieces of clothing that belong to someone else. A priest, for example. Also, the frying of eggs. There were so many times people cracked, beat, boiled or fried eggs in one draft of the book that I had to do a specific ‘egg edit’ just to whittle it down.

The changing of sheets. Beds to make, mattresses to flip, for all time. The scrubbing of floors or rugs. People down on their knees, ‘tamping’ the stain. It was important to me to write these moments into my novel.

Not only the dramatic moment when something is spilled – blood, semen – but also the person who must clean it up. (For ‘person’, read ‘woman’.) It was part of my point, in writing the novel, to account for the minutiae of everyday life and make it visible, what might once have been called ‘women’s work’.

But when I think about it, what inspires my interest in the everyday practices of domesticity – the quotidian, the ‘banal’ – goes beyond the project of writing a war novel that tries to resist the grand narratives of History. I’ve always been drawn to naturalistic, real-life detail in the work I admire, because of what it can reveal about the atmospherics of human interaction. The films of Joanna Hogg, for example, in the way that they are keenly tuned to the treachery and bathos of white, middle-class family life. There’s a moment in Archipelago where the son, played by Tom Hiddleston, is positioned clumsily in a bright bar of light just as a family photograph is being taken, an exquisitely subtle expression of sibling rivalry.

Or there are those observational moments in songs that put you right in the room. ‘Well Billie Joe never had a lick o’ sense / Pass the biscuits please,’ sings Bobbie Gentry in her ballad ‘Ode to Billie Joe’. There were particular songs I listened to repeatedly during the long and inefficient process of writing Violets, which I realise served as a conduit for this attention to the repeated gestures and small acts of everyday life. I would come downstairs for a break and stand in the narrow end of the kitchen in front of the CD player that is on top of the microwave, with the volume turned up, listening in order to get something out or let something in.

And I would play particular songs, standing very still and close, listening for particular lines. For example, in a live recording of Van Morrison’s ‘Ballerina’ he describes what seems like an oddly technical detail in a falling echo as if you can see the shaft of light:

The light [the light the light the light the light the light the light the light the light] was on the left side / Of your head / And I’m standing in your doorway / And I’m mumbling, mumbling and I can’t remember the last thing that ran straight through my head.

I know that shaft of light. I know that moment of inarticulate awe, the connection between seeing and feeling, being struck. And, trying as I was to write through the gaze of a woman whose exposure to the world was changing almost as if you could see her pupils dilate and adjust, listening to this song and waiting for this line and its echo to land, became an extension of writing, or maybe a precondition for it. For accessing that feeling, identifying with her desire.

There were other songs that worked in a similar way. PJ Harvey’s images of soldiers haunted by death even as they ‘rolled a smoke / told a joke’. And the embodied exactness of gunners hiding in the copses ‘with hearts that threatened to pop their boxes’.

Most often, perhaps, for atmosphere, for imagery, for attitude, I listened to Patti Smith at the beginning of the three-part song ‘Land’, from the album Horses.

‘Boy was in the hallway, drinking a glass of tea.’

That’s when I would be closest to the speakers, with just Smith’s voice, briefly, to set the scene. The hallway, a glass of tea; speaking so matter-of-factly to begin a song that goes on to pound through flame, sperm, surrender, switch blades and spume before it finally ends with the singular, base strut of a man: ‘Dancing / Around / To a simple / Rock and Roll / Song.’

I know that this isn’t quite the same as putting a detailed description of ironing in your book. The feeling of ironing a cloth and folding it crisply in half to iron it again (the satisfaction of it, the drudgery of it), or the act of ‘tamping’ a stain, a word and particular practice I have only ever known my mother use but think of whenever I find myself down on my hands and knees, wiping, cleaning. But what I hope have been left behind, are the residues of those everyday gestures, the love and care or jealousy and desire that they express, those small moments that somehow transcend their scale.

Image © Erich Ferdinand

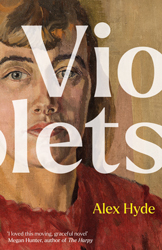

Alex Hyde’s debut novel Violets is published on 3 February 2022.