Prostitution, gambling, fencing, contract murder, loan-sharking, political corruption and crime of every sort were the daily trade in Philadelphia’s Tenderloin, the oldest part of town. The Kevitch family ruled this stew for half a century, from Prohibition to the rise of Atlantic City. My mother was a Kevitch.

Not all Jewish boys become doctors, lawyers, violinists and Nobelists: some sons of immigrants from the Pale became criminals, often as part of or in cahoots with Italian crime families. A recent history calls them ‘tough Jews’: men like Meyer Lansky and Bugsy Siegel, who organized and ran Murder Incorporated for Lucky Luciano in the ‘twenties and ‘thirties, and Arnold Rothstein, better known as Meyer Wolfsheim in The Great Gatsby, who fixed the 1919 baseball World Series. The Kevitch family were tough Jews.

Their headquarters during the day was Milt’s Bar and Grill at Ninth and Race, the heart of the Tenderloin, two miles north of Fourth and Daly. At night one or more male clan members supervised the family’s ‘after hours Club’ a few blocks away. We called Milt’s Bar the Taproom and the after hours club The Club.

The Taproom stood alone between two vacant lots carpeted with broken bricks and brown beer bottle shards. Bums, beggars, prostitutes, stray cats and dogs peopled the surrounding streets; the smell of cat and human piss was always detectable, mixed with smoke from cigarette and cigar butts smouldering on the pavement. Milt’s was a rectangular two-story building sixty feet long and eighteen feet wide. It fronted on the cobbles of Ninth Street and, through the back door, onto a cobbled alley. Both front and back doors were steel; the back door was never locked. The front window was glass block, set in The Taproom’s brown brick facade like a glass eye in an old soldier’s face. It could stop a fairly large calibre bullet and the wan light filtering through it brightened only the first few feet of the bar, the rest of which was too dark to make out faces.

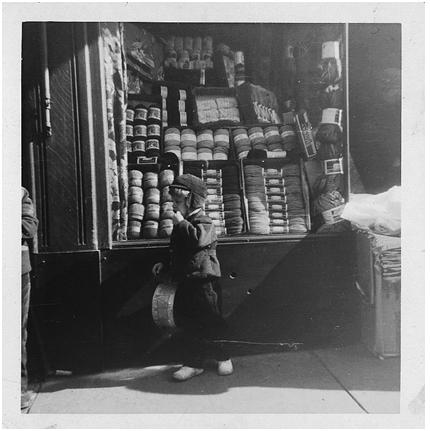

The author as a boy on 4th street.

More warehouse than pub, The Taproom served no food and little liquor. It was dank and smelled of stale beer, with too few customers to dispel either. I never saw more than a rummy or two drinking, or in the evenings perhaps a few sailors and a whore. The bar, with maybe a dozen stools, ran from the front door for a school bus’s length towards the rear. Three plain iron tables stood near the back door with two iron chairs each. One of these tables stood beside a large colourful Wurlitzer jukebox that only played when a Kevitch – Abe, Big Milt, Meyer or Albert – sat there to talk with someone. On those occasions one had to wonder how the two men heard each other and why their table was placed so close to the Wurlitzer it drowned them out.

I never visited The Club, which began life as a ‘speakeasy’ during Prohibition. My mother’s father, Milton or Big Milt (to distinguish him from his nephew, Little Milt) and his brother Abe owned The Club and a nearby illegal still. ‘G-men’, i.e. federal Treasury agents, raided the still one day, razed it and dumped its barrels of illegal alcohol in the gutters of the Tenderloin. Abe and Big Milt stood in the crowd as their hooch went down the drain and cheered the G-men on, as upright citizens should. The Kevitch family owned The Club for years after Big Milt and Abe died.

Big Milt was a Republican state legislator elected consistently for decades to represent the Tenderloin ward, which continued to vote ninety percent Republican for many years after the rest of the city went Democratic. It moved into the Democratic camp by a similar ninety per cent margin after the Kevitch family struck a deal with the Democratic leadership in the early 1950s. I had little contact with Big Milt, a distant figure who drove a black Lincoln Continental his state salary could not have paid for. He did not like my name and preferred to call me Donald. One birthday present from him of a child’s camp chair had Donald stencilled across its canvas back. He handled what might politely be called governmental relations for the family and died in The Club one night, aged sixty-seven, of a massive lung haemorrhage brought on by tuberculosis.

His brother Abe headed the Kevitch family and ran the ‘corporation’, the family loan-sharking business, along with the numbers bank, gambling, fencing, prostitution and protection. When I got into trouble with the police as a teenager, Uncle Abe told me what to say to the judge at my hearing and what the judge would do, then sat in the back of the courtroom as the judge gave me a second chance and I walked without a record. Abe sat on a folding canvas chair in front of The Taproom in good weather with a cigar in his mouth. Men came up to him from time to time to talk, and sometimes they would go inside to the table beside the jukebox and talk while the music played. Inclement days and winters found him behind the bar. All serious family matters were referred to Abe until he retired and Meyer, the elder of his two sons, took over.

Meyer always greeted me with Hello shit ass when my mother took us to The Taproom for a visit. In good weather he sat on the same chair outside the bar his father had, and had the same conversations beside the jukebox. But unlike Abe, he did not live in the Tenderloin, his Italian wife wore minks and diamonds, and his son attended college before becoming a meat jobber with lucrative routes that dwindled after his father died. Also unlike Abe, Meyer travelled, to Cuba before Castro, to Las Vegas and, in the 1970s, Atlantic City.

My father began playing in a local poker game and on his first two visits won rather a lot of money. The men running the game knew he was married to Meyer’s cousin. They complained to Meyer that they could not continue to let Joe win and Meyer told my father not to play there again. The game was fixed. Joe ignored him. At his next session they cleaned him out.

Meyer had a surprising reach. Joe briefly owned a meat business with a partner, Marty. It did well for eighteen months, the partners quarrelled bitterly, and Joe bought Marty out. A year later agents from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) criminal division began investigating my father’s affairs to discover whether he had been evading taxes by not reporting cash sales, which he and many other owners of cash businesses in the fifties certainly had done. The agents were getting closer and jail loomed.

Joe spoke to Meyer, who told him several days later, ‘Joe, it’ll cost $10,000’, a large sum then and one Joe couldn’t raise. Meyer suggested he ask his ex-partner to pay half since the IRS audit covered the partnership years. Marty told my father, ‘I’ll give it to you when you need it for bread for your kids’. Joe reported this to Meyer, but the price remained $10,000. Joe put a second mortgage on our house which Abe co-signed, paid Meyer, and three days later the IRS agent called and said, ‘Mr Burt, I don’t know who you know, and I don’t know how you did it, but I’ve had a call from the IRS National Office in Washington, DC, ordering me to close this case in one week.’

A year later the IRS criminal investigators returned, this time to audit Marty. Nothing Marty’s tax lawyers could do put them off. He begged Joe to ask Meyer for help. But this time Meyer said there was nothing he could do. Marty endured a long trial which ended in a hung jury. Before the IRS could retry him he dropped dead of a heart attack; he was forty-six.

My mother’s brother, Albert, was a taciturn man. He lived with his wife, Babe (neé Marian D’Orazio), and their four girls in a row home at 24th and Snyder in South Philadelphia’s Italian neighbourhood. He had no son. Babe was a great beauty, hence the nickname which she still bears proudly at ninety-two, and her daughters were beautiful as well. From the street their house looked like any other working class row home in the neighbourhood, but inside it brimmed with toys, televisions, clothes and delicacies; the daughters were pampered and much envied. Education for Uncle Al, Aunt Babe and their daughters stopped with South Philly high. They attended neither church nor synagogue. There were no books on their tables or art on their walls, except a mural of a bucolic Chinese landscape in their living room.

Uncle Al was a detective on the Vice Squad, the Philadelphia police department’s special unit charged with reducing prostitution, gambling, loan-sharking, fencing, protection and other rackets. The opportunities for corruption were many; some said the Vice Squad’s function was to protect vice. Clarence Ferguson was the head of the Vice Squad. Babe’s sister was Ferguson’s wife.

We went to visit Uncle Al’s house one Sunday when I was ten. A week before, Billy Meade, the boss of the Republican machine in Philadelphia, had been shot and nearly killed in The Club. He was drinking in the early hours at his accustomed spot at the bar when someone shot him with a silenced pistol shoved through the inspection grill in the door when it was slid aside in answer to a knock. The shooter was short, he stood on a milk crate to fire through the grill, and must have known Meade could be found in The Club in the wee hours of Sunday morning and where along the bar he customarily stood.

Billy Meade and Big Milt, Uncle Al’s father, were on the outs at the time and Meade had done something that caused Big Milt real trouble. Uncle Al was just five feet five, had ample experience with and access to firearms, and would have known Meade frequented The Club. I watched the police take Uncle Al from his house that morning and confiscate a large chest containing his sword and gun collection. He was tried but not convicted because the weapon used was never found and Babe said he had been making love to her in their marriage bed when the shooting occurred. No one else was accused of the attempted murder, and when Meade recovered he made peace with Big Milt. They both died of natural causes.

Some years later Uncle Al was again involved in a shooting. This time there was no question that he was the shooter. He had stopped for a traffic-light in a rough neighbourhood on the way home from work. Four young black men approached his car. According to Al they intended to car-jack him.

I never saw Uncle Al without his gun, a .38 police revolver he wore in a holster on his belt. When he drove he always unholstered the gun and laid it on the seat beside him. One of the men tried to open the driver’s door and Uncle Al grabbed his gun from the seat and shot through the window, seriously wounding him. The other three fled and Al chased them, firing as he went. He brought down a second and the other two were picked up by the police a short time later.

The papers were full of pictures of the car’s shattered windows, the two black casualties and the white off-duty detective who had shot them. The police department commended him for bravery. I never saw Uncle Al angry; crossed, he stared at you coolly with diamond blue eyes and sooner or later, inevitably, evened the score and more.

All the Kevitch men of my grandfather’s and mother’s generation had mistresses and did not disguise the fact. Their wives and all the mistresses were Gentiles, excepting Abe’s wife, Annie. Uncle Al had a passion for Italian women and consorted openly with his Italian mistress for the last twenty-five years of his life. Divorce was not unheard of in the family, but Al died married to Babe.

One of Uncle Al’s daughters described her father by saying He collected. The things he collected included antique swords, guns, watches and jewellery, as well as delinquent principal and interest on extortionate loans the family ‘corporation’ made; protection money from shopkeepers, pimps, madams, numbers writers, gambling dens, thieves and racketeers; and gifts from the Philadelphia branch of the Gambino Mafia family run by Angelo ‘the gentle don’ Bruno. Joe and Uncle Al died within months of each other, and at Joe’s funeral Babe proudly told me how Al would make the more difficult collections, say from a gambler who refused to pay his debts. He would cradle his ’38 in the flat of his hand and curl his thumb through the trigger guard to hold it in place, so it became a second palm. Then he’d slap the delinquent hard in the head with his blue steel palm. His collection record was quite good.

Angelo Bruno and Uncle Al were close for years, until Bruno was killed in 1980 at the age of sixty-nine by a shotgun blast to the back of his head. Albert had protected him and his lieutenants from arrest. In exchange Bruno contributed to Uncle Al’s collections. Uncle Al often told his daughters what a wonderful, decent, kind man Bruno was and that he did not allow his family to deal in drugs. The Albert Kevitch family held the Don in high regard.

Babe adored her husband and my four cousins adored their father. They were grateful for the luxurious lives he gave them and proud of the fear he inspired. No one bullied them. Babe called the four girls together before they went to school the day the newspapers broke the story of Al’s arrest on suspicion of shooting Billy Meade and told them if anyone asked whether the Al Kevitch suspected of the shooting was their father they should hold their heads up and answer Yes.

My mother, Louise Kevitch, Albert’s younger sister, was born to Milton and Anita Kevitch (née Anita Maria Pellegrino) a block or two from The Taproom in 1917. Nine months later my maternal grandmother, Anita, a catholic, died in the 1918 flu epidemic and her children, Louise and Albert, were taken in by their Italian immigrant grandmother, who lived nearby. She raised Louise from the age of two until thirteen in an apartment over her candy store, its profits more from writing numbers than selling sweets. Louise was thirteen when her grandmother died; she lived with Uncle Abe and Aunt Annie in their large house across the street from The Taproom from then until, at twenty-one, she married my father.

Louise graduated from William Penn High School in central Philadelphia, wore white gloves out and about and shopping in the downtown department stores, went to the beauty parlour once a week and had a ‘girl’, a black maid, three days a week to clean and iron, a luxury that Joe could ill afford. She did not help him in the store. She spoke reverentially of her brother, Al, and his role as a detective on the Vice Squad, of Big Milt, who worked in Harrisburg, and of Uncle Abe and the family ‘corporation’, which would help us should we need it. Meyer was Lancelot to her, though we never quite knew why. Louise constantly invoked the principle of ‘family’ as a mystic bond to be honoured with frequent visits to Taproom and Kevitches. Joe did all he could to keep us from their ambit. It was a child-rearing battle he won, but not decisively. Louise kept trying to force us closer to her family; they fought about it for fifty-three years.

My mother never bentsch licht or went to schul, except on the high holidays, Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur. She never told us her mother and grandmother were Italian. When Babe revealed the secret to me, Louise didn’t speak to her for months. We never knew her father had married another Gentile shortly after her mother (Anita) died, and fathered aunts and uncles we never met. She never mentioned Big Milt’s mistress, Catherine, who was with him at his death. She never explained how four families – Abe and Annie, Meyer’s, his brother Milton’s first and second ones – lived well on earnings of what appeared to be a failing bar and after-hours club in the red light district. Why her brother was so important if he was only a detective, how his family lived so well on a detective’s salary – these were never explained. She did not tell us her mink coat was a gift from her brother, or how he came by it. Any questions about what Uncle Al or Meyer actually did, any suggestion that any Kevitch male was less than a gentleman infuriated her, brought slaps or punishment, and went unanswered. We learned about the Kevitches from observation, from what they told us, and from the papers.

The above is an excerpt from You Think It Strange: A Memoir by Dan Burt, out November 11th from Notting Hill Editions.

Featured photograph by Dan Grogan; photgraph of Dan Burt courtesy of Dan Burt