It’s dark and deathly quiet in here. The sheets of the bed are cool and laundry-smelling, but there’s a niff in the air, sweet and sickly, like dead chrysanthemums. Sleep has disassembled the self: it will take patience to rebuild a person out of the heap of components in the bed. The dial of a wristwatch looms in front of a single open eye; its luminous green hands say that it is either twenty-five after midnight or five in the morning. The spare human hand goes out on a cautious reconnaissance patrol through the darkness. It snags on a sharp corner, knocks over a bottle of pills, finds a solid, cold ceramic bulge. Fingers close on the knurled screw of the switch, and the room balloons with light.

It’s a conventioneers’ hotel room. The waking eye takes in the clubland furniture in padded leatherette, the Audubon prints, the thirty-six-inch TV mounted over the mini-bar, the heavy cream drapes across the window. The room is painlessly impersonal, artfully designed to tell the self nothing about where it is or who it is supposed to be. It looks like its price. It is just a seventy-five-dollar room.

The nose sources the bad smell to a tooth-glass of scotch and tap-water on the bedside table. The time is five o’clock but feels later.

Does seventy-five dollars buy twenty-four-hour room service? The shallow drawer below the telephone ought to yield a hotel directory, but doesn’t. It contains two books of the same size and in the same binding: a Gideon Bible and The Teaching of Buddha, in English and Japanese, donated (it says) by the Buddhist Promoting Foundation, Japan. This is the room’s first and only giveaway. The hotel where Jesus and Buddha live side by side in the drawer is on the Pacific Rim. The text is printed on thin crinkly paper.

A true homeless brother determines to reach his goal of Enlightenment even though he loses his last drop of blood and his bones crumble into powder. Such a man, trying his best, will finally attain the goal and give evidence of it by his ability to do the meritorious deeds of a homeless brother.

There’s no reply from room service on 107, so, sitting up in bed, long before dawn and Good Morning America, I read Gautama for the first time and find his teaching interestingly apposite to the situation and the hour.

Unenlightened man, said the Buddha, was trapped in an endless cycle of becoming – always trying to be something else or somebody else. His unhappy fate was to spend eternity passing from one incarnation to the next, each one a measure of his ignorant restlessness and discontent. In the search for Nirvana, man must stop being a becomer and learn how to be a be-er.

It is a profoundly un-American philosophy. Here in this travellers’ room, in this nation of chronic travellers and becomers, The Teaching of Buddha strikes the same note of disregarded truth as the health warning on an emptied pack of cigarettes. The idea that the whole of the external world is a treacherous fiction, that the self has no real existence, goes right against the Protestant, materialist American grain.

No wonder that so many Americans have looked across the Pacific to Buddhism to provide an antidote to the American condition. Emerson and the New England Transcendentalists – Whitman – T. S. Eliot – the Dharma Bums – J. D. Salinger – Robert M. Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance: in every phase of post-colonial American history, Buddhism has offered a rhetoric of dissent; and on the Pacific coast it has coloured the fabric of the culture.

I look at the advice I’ve failed to follow –

In the evening he should have a time for quiet sitting and meditation and a short walk before retiring. For peaceful sleep he should rest on the right side with his feet together and his last thought should be of the time when he wishes to rise in the early morning.

– and copy it into my notebook. It sounds like a good tip; far better than pills and whisky.

Fiction or not, the external world is beginning to make its presence felt now. The drapes open on a city still blue in the half-light. Lines of cars on the wet streets a few floors below the window are making a muffled drumming sound; the morning commute from the suburbs is already underway. Seven o’clock. It’s time to shave and shower; time to put Buddha back in the drawer and become someone else.

On that particular morning, in hotels and motels, in furnished rooms and cousins’ houses, 106 other people were waking to their first day as immigrants to Seattle. These were flush times, with jobs to be had for the asking, and the city was growing at the rate of nearly 40,000 new residents a year. The immigrants were piling in from every quarter. Many were out-of-state Americans: New Yorkers on the run from the furies of Manhattan; refugees from the Restbelt; Los Angelenos escaping their infamous crime statistics, huge house-prices and jammed and smoggy freeways; redundant farm workers from Kansas and Iowa. Then there were the Asians – Samoans, Laotians, Cambodians, Thais, Vietnamese, Chinese and Koreans, for whom Seattle was the nearest city in the continental United States. A local artist had proposed a monumental sculpture, to be put up at the entrance to Elliott Bay, representing Liberty holding aloft a bowl of rice.

The falling dollar, which had so badly hurt the farming towns of the Midwest, had come as a blessing to Seattle. It lowered the price abroad of the Boeing airplanes, wood pulp, paper, computer software and all the other things that Seattle manufactured. The port of Seattle was a day closer by sea to Tokyo and Hong Kong than was Los Angeles, its main rival for the shipping trade with Asia.

By the end of the 1980s, Seattle had taken on the dangerous lustre of a promised city. The rumour had gone out that if you had failed in Detroit you might yet succeed in Seattle – and that if you’d succeeded in Seoul, you could succeed even better in Seattle. In New York and in Guntersville I’d heard the rumour. Seattle was the coming place.

So I joined the line of hopefuls.

Of all the new arrivals, it was the Koreans who had made the biggest, boldest splash. Wherever I went, I saw their patronyms on storefronts, and it seemed that half the small family businesses in Seattle were owned by Parks or Kims. I picked up my trousers from the dry-cleaner’s at the back of the Josephinum, stopped for milk and eggs at a Korean corner grocery, looked through the steamy window of a Korean tailor’s, passed the Korean wig shop on Pike Street, bought oranges, bananas and grapes from a Korean fruit stall in the market, and walked the hundred yards home via a Korean laundromat and a Korean news and candy kiosk.

For lunch I went to Shilla, where I sat up at the bar, ordered a beer, and tried to make sense of the newspaper which had been left on the counter – the Korea Times, published daily in Seattle. The text was in Korean characters, but the pictures told one something. There were portrait photographs of beaming Korean-American businessmen dressed, like many of the restaurant’s customers, in blazers, button-down shirts and striped club ties. Several columns were devoted to prize students, shown in their mortar boards and academic gowns. On page three there was a church choir. There was a surprising number of advertisements for pianos. I guessed that the tone of the text would be inspirational and uplifting: the Korea Times seemed to be exclusively devoted to the cult of business, social and academic success.

‘You are reading our paper!’ It was the proprietor of the restaurant, a wiry man with a tight rosebud smile.

‘No – just looking at the pictures.’

He shook my hand, sat on the stool beside me and showed me the paper page by page. Here was the news from Korea; this was local news from Seattle and Tacoma; that was Pastor Kim’s family advice column; these were the advertisements for jobs…

‘It is very important to us. Big circulation! Everybody read it!’

So, nearly a hundred years ago, immigrant Jews in New York had pored over the Jewish Daily Forward, the Yidishe Gazetn and the Arbeite Tseitung. They had kept their readers in touch with the news and culture of the old world at the same time as they had taught the immigrants how to make good in the new. To the greenhorn American, the newspaper came as a daily reassurance that he was not alone.

‘You are interested?’ the restaurateur said. ‘You must talk to Mr Han. He is the president of our association. He is here –’

Mr Han was eating by himself, hunched over a plate of seafood. In sweatshirt and windbreaker, he had the build of a bantamweight boxer. The proprietor introduced us. Mr Han bowed from his seat, waved his chopsticks. Sure! No problem! Siddown!

His face looked bloated with fatigue. His eyes were almost completely hidden behind pouches of flesh, giving him the shuttered-in appearance of a sleepwalker. But his mouth was wide awake, and there was a surviving ebullience in his grin, which was unselfconsciously broad and toothy.

He gave me his card. Mr Han was President of the Korean Association of Seattle, also owner of Japanese Auto Repair (‘is big business!’). He had been in America, he said, for sixteen years. He’d made it. But his college-student clothes, his twitchy hands and the knotted muscles in his face told another story. If you passed Mr Han on the street, you’d mistake him for a still shell-shocked newcomer; an FOB, as people said even now, long after the Boeing had displaced the immigrant ship. He looked fresh off the boat.

It had been the summer of 1973 when Won S. Han had flown from Seoul to Washington DC with 400 dollars in his billfold and a student visa in his passport. He had come to study psychology – that was what his papers said, at least – but what he really wanted to major in was the applied science of becoming an American.

In Korea, he had been brought up as a Buddhist. Within two weeks of his arrival in Washington, he was a Baptist.

‘Yah! I become Christian! I didn’t go to church to believe in God, not then, no. I go to church for meeting people. Yah. Baptist church was where to find job, where to find place to live, where to find wife, husband, right? In America, you gotta be Christian!’ His voice was lippy, whispery, front-of-the-mouth.

He’d soon fallen behind in his psychology classes. He couldn’t follow the strange language. Through the church, he found a part-time job in a gas- and service-station. He learned the work easily. While the American workers were content to lounge and smoke and tinker, this university-educated Korean gutted the car manuals and took only a few weeks to qualify as a full-fledged auto mechanic.

‘We are hot-temper people! Want to do things quick-quick-quick! Not slow-slow like in America. Want everything all-at-once, but in America you must learn to wait long-time. Quick-quick is the Korean way, but that’s not work here. America teaches patience, teaches wait-till-next-week.’

This must have been a hard lesson for Mr Han to take to heart. He’d done a major reconstruction job on the American language to give it a greater turn of speed, lopping off articles, prepositions, all the fancy chrome work of traditional syntax. His stripped-down English was now wonderfully fast and fluent. With its rat-a-tat-tat hyphenations and bang! bang! repetitions, it was a vehicle custom-built for its owner – a Korean racing machine in which Mr Han drove with his foot on the floor, without regard for petty American traffic restrictions.

Working as a mechanic by day, he’d gone to school at night. This time his subject was real estate, and it took him six months to qualify for a Maryland realtor’s licence. He gave up the car business and sold suburban houses, mostly to Korean customers.

‘You know, when Korean guy come to this country, he has plan! In two year, must have own business. In three year, must have own house. Three year! Four at maximum. So must work-work-work. Sixteen-hour-day, eighteen-hour-day… OK, he can do. But must have business, must have house.’

Mr Han himself had run ahead of schedule. By 1982, when he left Washington and headed for Seattle, he was a man of capital with a wife and two young daughters. To begin with, he patrolled the city from end to end by car, casing the joint for opportunities.

‘And you liked what you saw?’

‘Yah! I like the mountains! Like the water! Like the trees! Is like in Korea, but not too hot, not too cold. Nice! No people! Green!’

Everywhere he’d gone, he’d checked in with the local Parks and Kims and got the low-down on Seattle’s social structure. Beacon Hill, just south of downtown, was where Korean beginners started their American lives; as they succeeded, so they moved further north, to Queen Anne and Capitol Hill, across Lake Washington to Bellevue, across Lake Union to Wallingford, Morningside, Greenwood, North Beach. They measured the tone of a neighbourhood by the reputation of its schools. The top suburb was the one with the best record of posting students to famous American colleges like Columbia, Yale and MIT.

On his first day in Seattle, Mr Han had learned that the Shoreline School District was ‘much better, no comparison!’ than the Seattle School District, and that the Syre Elementary School was just the place for his daughters to set foot on the ladder to academic stardom. So he bought a house in Richmond Beach. He had no Korean neighbours. The closeness of the house to the school was all that mattered.

Then he set up his business.

‘Must be specialist!’ Mr Han said. Detroit was sick, and more and more Americans were buying Japanese cars, so Mr Han established his hospital for Japanese cars only. ‘No American cars! No German! No English! – sorry! Must be Japanese. Toyota, Nissan, Mitsubishi, whatever. So long as it made in Japan – bring it in! That is my speciality.’

The climax of this success story had happened two years ago. Mr Han had always dreamed of having a son to carry on the Han dynastic name. In Korea, it was a woman’s highest duty to give birth to a son. Mr Han himself was the only son of an only son – a man genetically programmed to produce a male heir. But it seemed that he could only father daughters. This was, he said, a heavy fate for a Korean man to shoulder.

‘So, in 1986, I go to my wife. I say to her, “One last try!” And we try. And – Home Run!’ For the first time, Mr Han’s eyes were wide open, his pride in this feat of paternity matched by this rich nugget of all-American slang.

‘Home run!’ He smacked his lips around the phrase and laughed, a joyful hoo! hoo! that made neighbouring diners look up from their tables.

‘Now the name of Han goes on!’

With his business in the city, his civic honours in the Korean community, his big house in a wooded, crimeless suburb a spit away from the sea, his straight-A daughters and his precious son, one might have expected Mr Han to have grown expansive and complacent in his New World estate. Yet his eyes closed as quickly as they had opened; he fell back into hunched vigilance; he looked, as I had first seen him, like an anxious greener who fears that someone, somewhere, is hard on his heels.

He was frightened for his children.

‘They see the American TV… of this I am scared. I turn off the news. There is too much immorality! Violence! Drugs! Sex! When the news comes up – “Turn that TV off!”’

He had tried to turn his home into a Korean bubble, sealed off from the dangerous American world outside. In the house, the family talked in Korean. Twice a week, the girls went to a Korean church school to take classes in Korean grammar and composition.

He dreaded the day when one of his daughters would bring home a white American boyfriend.

‘What would you do?’

‘Any kid of mine, I’d stop her marrying another race.’

‘Stop!’

‘Maybe could not stop. Maybe. But not like. You heard of “GI Brides”… They were not normal average Korean woman. They were – I not say exactly what they were, but you know what I mean.’ Mr Han watched me across the table through his nearly closed eyes. ‘Whores,’ he said, making the word sound biblical.

I said that the Jews in New York at the beginning of the century had felt much as he did. But they had had the protection of the ghetto. In the Yiddish-speaking world of the Lower East Side, with its all-Jewish streets and all-Jewish schools, it was possible to regard the goyim as unmarriageable aliens. In Richmond Beach, a Korean girl would be a Christian, like most of her classmates, and her skin colour would be hardly less pale than theirs. How, growing up in English, could she hug ‘Koreanness’ to herself as the essence of her identity, while all the time her parents talked Columbia, talked medical school, talked her up the path that led to membership of the white, professional, American middle class?

‘Ah,’ said Mr Han. ‘This is what we are wondering. Wondering-wondering all the time. How long? is the question. In near future, next generation, we got to be serviced by English. We have example of Chinese. Look at Chinese! – in two-three generations, the Chinese people here, they cannot even read the characters! Chinese is only name. Is nothing. Now, Chinese… all in the melting pot!’ He drew out this last phrase with solemn relish. The way he said it, it was a mel Ting pot, and I saw it as some famous cast-iron oriental cooking utensil, in which human beings were boiled over a slow fire until they broke down into a muddy fibrous stew.

‘But my kids grow like Koreans,’ Mr Han said.

‘With American voices, American clothes, American college degrees…’

‘Like Koreans.’

On the street across from the restaurant I could see a rambling black-painted chalet surmounted by a flying hoarding which said: LOOK WHAT WE GOT! 30 NUDE SHOWGIRLS! TABLE DANCING! It was a sign to chill the heart of a Korean father of young daughters.

Since so much of American culture was clearly a Caucasian affront to Korean ideas of modesty, industry, piety and racial purity, I wondered why they kept on coming – from a country that was being touted as the economic miracle of the decade.

Mr Han guffawed when I said ‘economic miracle’.

‘Guy in Korea make three-four-hundred dollar a month. No house his own, no business his own. This is country of opportunity. No comparison. Chance of self-employment: maybe one thousand per cent better! Look. Seventy-three. I am in Washington, DC with four hundred dollars. Now? My business is worth one million dollars – more than one million. Heh? Isn’t that the American Dream? And I am only a small! Yes, I am a small.’

Minutes later, I watched him as he crossed to his car. The millionaire was walking quick-quick-quick, shoulders hunched, head down, his skinny hands rammed deep into the pockets of his workpants. He looked like a man who had taken on America single-handed and, in the ninth round, was just winning, by a one- or two-point margin.

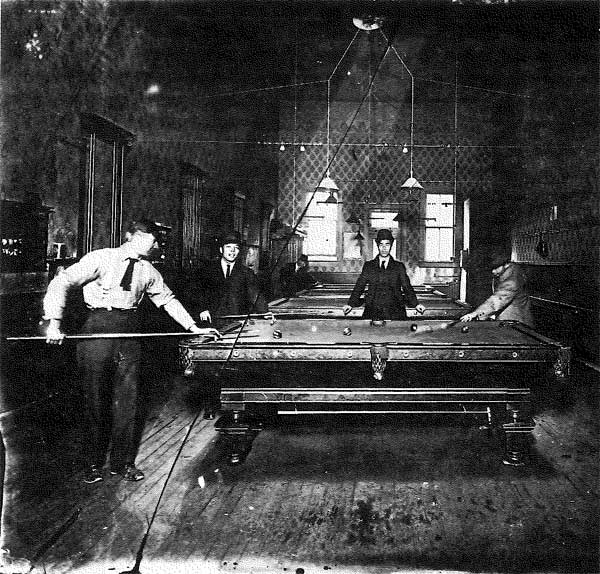

Seattle, circa 1900

The Chinese had been the first Asians to make a new life in Seattle. They called America ‘The Gold Mountain’ and were eager to take on the hard, poorly paid jobs that were offered to them in the railroad construction gangs. For as long as it took to build the railroads, they were made welcome, in a mildly derisive way. Their entire race was renamed ‘John’, and every John was credited with an extraordinary capacity to do the maximum amount of work on the minimum amount of rice. As soon as the railroads began to lay off workers, the amiable John was re-conceived as ‘a yellow rascal’ and ‘the rat-eating Chinaman’. During the 1870s, the federal legislature began to behave towards the Chinese much as the Tsars Alexander II and Nicholas II behaved towards the Jews in Russia. At the very moment when the United States was receiving the European huddled masses on its eastern seaboard, it was establishing something cruelly like its own Pale, designed to exclude the Chinese from white American rights and occupations. The Geary Act prohibited the Chinese from the right to bail and habeas corpus. In Seattle in 1886, gangs of vigilantes succeeded in forcibly deporting most of the city’s Chinese population of 350 people; persuading them, with knives, clubs and guns, to board a ship bound for San Francisco.

For the immigrant from Asia, the Gold Mountain was a treacherous rock-face. No sooner had you established what seemed to be a secure foothold than it gave way under you. The treatment of the Seattle Chinese in 1886 was matched, almost exactly, by the treatment of the Seattle Japanese in 1942, when hundreds of families were arrested, loaded on trains and dispatched to remote internment camps.

Now, if you came from Asia, you could not trust America to be kind or fair. This particular week, if you went to an English class at the Central Community College, you would see spray-gunned on the south wall of the building SPEAK ENGLISH OR DIE, SQUINTY EYE! Peeing in a public toilet, you’d find yourself stuck, for the duration, with a legend written just for you: KILL THE GOOKS.

In the ghetto of Seattle’s International District, a four-by-four block grid of morose, rust-coloured tenements, there was at least safety in numbers. There was less pressure on the immigrant to get his tongue round the alien syllables of English. Even a professional man, like the dentist or optometrist, could conduct his business entirely in his original language. In the bar of the China Gate restaurant, I sat next to a man in his early seventies, born on Jackson Street, who had served with the United States Air Force in World War Two. He was affable, keen to tell me about his travels and almost completely incomprehensible:

‘Yi wong ding ying milding hyall!’

‘You were in Mildenhall? In Suffolk?’

‘Yea! Milding Hall!’

So, painfully, we swapped memories of the airbase there. He didn’t understand much of what I said, and I didn’t understand much of what he said; yet his entire life, bar this spell in wartime England, had been passed in Seattle – or, rather, within the Chinese-speaking fifty-acre grid.

The Chinese, the Japanese, the Vietnamese, Laotians and Cambodians had all established solid fortresses in, or on the edge of, the International District. There were few Koreans here. There was the Korean Ginseng Center on King Street; there was a Korean restaurant at the back of the Bush Hotel on Jackson; some Koreans worked as bartenders in the Chinese restaurants.

In Los Angeles, there was a ‘Little Korea’; a defined area of the city where the immigrant could work for, and live with, his co-linguists, much as the Chinese did here in the International District. For Koreans in Seattle, though, immigration was, for nearly everyone, a solitary process. The drive to own their own businesses, to send their children to good schools, to have space, privacy, self-sufficiency, had scattered them, in small family groups of twos and threes, through the white suburbs. They didn’t have the daily solace of the sociable rooming house, the street and the café. For many, there was the once-a-week visit to church; for others, there was no Korean community life at all.

It was this solitude that drew me to them. The Seattle Koreans knew, better than anyone else, what it was like to go it alone in America; and although I came from the wrong side of the world I could feel a pang of kinship for these people who had chosen to travel by themselves.

Everyone could name the date on which they’d taken the flight out from Seoul. The beginning of their American life was at least as important to them as their birthday.

‘August twenty-ninth, 1965,’ Jay Park said. He owned a plumbing business up on Beacon Hill and drove a pearl-grey ’88 Mercedes. In 1965, he’d been twenty; and on that August afternoon he’d stood in Seoul airport being hugged by every aunt, cousin, uncle, friend.

‘Everyone envy me. It was like I’d won the big lottery, you know? I’d got the visa! Wah! They was seeing me off like I was some general… like I was going into Paradise!’

Park knew America. He’d ‘watched it through the movies’. On the streets of Seoul, he’d seen ‘US soldiers spending money like it was going out of style. Wah! I tell you, the US was like a paradise. You feel like you’re going to dreamland. Everything’s going to work out OK!’

It was a Northwest Airlines flight; Jay Park had never been on an airplane before and he had ‘not one word’ of English. The stewardess showed him to an aisle seat, next to an American who was reading a book.

‘He don’t look at me. I felt shy. Suddenly I was kind of scared, the excitement was overwhelming. This guy was reading his book, so I read the in-flight magazine. I mean, not read, but made out like I was reading. I was just looking at the pictures of the US, but I was taking a long time over every one, so this guy would think I could read the English.’

The plane took off. ‘No problem,’ but Jay Park wished he could see out the window. He didn’t dare to lean across the body of his American neighbour; so, holding the magazine close to his face, he’d sneaked glances – seen jigsaw puzzle bits of city and mountain slide past the lozenge of perspex as the plane banked.

A meal was served. ‘That was real great! American food! I was in the US already!’

At Tokyo they had stopped to refuel. Jay Park was in an agony of impatience. Other Koreans on the flight were buying watches and radios at the Tokyo duty-free shop, but Jay Park sat fretting on a bench during the stopover, his mind full of America.

Then came the long haul across the Pacific. They left the sunset behind – Park could see it gleaming gold on the trailing edge of the plane’s starboard wing – and flew into the night. He remembered the blinds being pulled down for the projection of the movie. With no headset, he could only watch the pictures – more postcards of America. ‘Oh boy! Dis is where I’m goin’! I’m in the movie!’

Exhausted by his excitement, he fell asleep. When he woke up, the quick night was already over. Time itself was whizzing by faster than the clouds below, but the plane was still a long way from America. The morning lasted forever. ‘Then – they were saying something through the speaker, but my ears were blocking up. Seattle! That’s all I hear. Seattle!’

There was nothing to see. America was a huge grey cloud, through which the plane was making its unbearably slow descent. When it touched down, Jay Park was high, in a toxic trance.

‘Wah! Man! The airport! When you’re walking through, your mind is set, “This is America!” Everything is nice! great! fantasy!’

The air inside the terminal was magic air. It smelled of cologne and money. There were advertising posters for things – ‘I don’t know what they are, but, boy, they look good to me!’

The two hours he spent standing in line, waiting to be processed by the immigration officials, were precious, American hours. ‘No, I don’t care! I just think, Wah! I’m in the US!’

His sponsors were waiting for him in the arrivals lobby, a Korean-American couple in their forties who had been friends of his parents back in Seoul. Jay Park had never met them before, but they were holding up a sheet of cardboard with his name on it.

‘Oh, but they’d done great! I was expecting them to take me in a bus, but they got their own car! A Chevy. Blue. Musta been a ’63, ’64 model. Yeah. Nice long sheer, box type, really fancy! You sitting in the back seat, looking out, it astounds. Wow! All the freeways, all the cars!’

The blue Chevy drove north, up the I-5 towards Seattle.

‘Whassat? Hey, goddam, whassat?’

Jay Park saw a great factory – but it wasn’t a factory; it was a supermarket. He loved the huge pictures raised over the six-lane highway, the smoking cowboys, the girls in swimsuits. Wah! America!

‘Then, passing the downtown, goddam! The Smith Tower! The Space Needle! Godawmighty! You gotta look at that! But so few people! There was hardly any peoples was there! No people, hardly. You feel uneasy. What’s going on? Is the people all gone home? This is real strange, not having people around. In Korea, people everywhere; in America – no people!’

The Chevy left the 1-5 and headed up Aurora Avenue, along the wooded edge of Lake Union. It crossed the George Washington Bridge and entered the northern suburbs.

‘It was the cleanness! The cars parked neatly! Just like the movies! And the lawns… No fences, no walls. In Korea, it was all high stone walls round every house. Here, is all open, all lawns, lawns, lawns. Looking out the car window, I see people’s bikes left out front, just like that… like, here you can just leave things out overnight. No thieves! I think, everything is coming true! What the movies say is true! This is like paradise is supposed to be!’

His sponsors lived in a neat frame house in Greenwood.

‘They had tables and chairs, the American way, not all on the floor like in Korea. Wah, man! I was cautious, then. Like, first thing, I want to use the toilet, you know? They show me where it is, and I spend a long, long time just looking around in there, like, If I use it, where’s the smell going to go! Oh! I get it! There’s the fan! Stuff like that. Little things. Then they show me the bed where I’m to sleep? I never slept on a bed before. I think, how you sleep on a bed without falling off? I fell out of that bed a few times, too.’

That evening, his sponsors took Jay Park to the local supermarket.

‘Wah! The steaks! The hamburgers! To eat a whole piece of meat! Even chickens! And they’re so cheap too!’

He slept on the strange bed in a state of delirious wonder, his dreams far outclassed by America’s incredible reality. In the morning, he ventured out into the backyard. A man – a white American – was pottering in the garden next door.

‘He said to me, “Hi!” and then he said something. I didn’t say anything. I think I give him a smile… I hope I give him a smile… then I go back into the house. They speak English out there!’

But: ‘I was ready to tackle anything, anyhow.’ With his sponsors’ help, he enrolled for classes twice a week at the Central Community College. He got a job as a porter at a dry-ice factory. It paid $1.25 an hour – ‘great money!’ He found lodgings, with an Italian woman who worked at a downtown grocery and mothered him. Bed and board cost him thirty-five dollars a week; but as soon as work was over at the factory, Jay Park was out mowing people’s lawns. If he put in a sixteen-hour day, he could make 120 dollars in a week – a fortune. In his new Levis and his long-brimmed baseball cap, Jay Park was living the movie as he toted ice and mowed grass.

‘Downtown, though, that was a big shock for me. You look – wah, godawmighty! – really strange people! Those poor whites, down in skid row? You never expecting skid row to exist in a country like this! I never seen that in the movies.’

He was having a hard time with the language. He went to his classes. He sat up late every night, slogging over his homework. He studied the programmes he saw on television, treating Hogan’s Heroes as a set text. ‘I want something, I get it,’ Jay Park said, but he couldn’t get English.

‘There was such pain building up inside me… People say things at work, I can’t answer back! There’s no language there! Nothing in the mouth! So you must make physical movement, you know? You get violent!’

So he punched and jabbed to make himself understood. Lost for a word, he socked the American air and laid it flat.

He was making out. He was saving. After a year of lawn-mowing and digging out borders, he was able to bill himself as ‘Jay Park – Contractor and Landscape Gardener’, but he was still travelling across Seattle by bus. It took him until 1967 before he’d put away enough to buy his first car.

‘It was a 1960 T-Bird. Light blue. Electric windows and everything else. You owning own car, wah! That was a thrill, man.’

Now he drove his Italian landlady everywhere. She was chauffeured to work, chauffeured around the stores. Waiting for her, parked on the street, Jay Park, Contractor, Landscape Gardener, Ice Merchant, American, sat behind the wheel listening to the music of his electric windows buzzing up and down. ‘Boy, I loved that car!’

Their experience had turned the immigrants into compulsive storytellers. Much more than most people, they saw their own lives as having a narrative shape, a plot with a climactic denouement. Each story was moulded by conventional rules. Korean men liked to see themselves as Horatio Alger heroes. Once upon a time there had been poverty, adversity, struggle. But character had triumphed over circumstance. The punchline of the story was ‘Look at me now!’, and the listener was meant to shake his head in admiration at the size of the business, the car, the house, at the school and college grades of the narrator’s children, and at the amazing fortitude and pluck of the narrator, for having won so much in this country of opportunity. The story, in its simplest form, was a guileless tribute both to the virtues of the Korean male and to the bounty of America.

I preferred to listen to the stories of the women. They were closer to Flaubert than to Alger; their style was more realistic; they were more complicated in structure; they had more regard for pain and for failure.

Insook Webber took the flight for Seattle on 23 April 1977.

‘I’d never been in an airplane before, but I loved – I absolutely adored – the idea of flying. I loved to see the planes in the sky. For me, they were flying into – like a fantasy world? A world of possibilities. And I had this premonition. It was always inside me, that somehow, someday, I’d leave Korea.’

She was in her thirties now, fine-boned, fine-skinned, her hair grown down to her shoulders in the American way. Her English was lightly, ambiguously, accented. In silk scarf and chunky cardigan, she looked dressed for a weekend in the Hamptons. She was married to an American; a Yale philosophy graduate who chose to work, unambitiously, in an accountants’ office. She herself was a hospital nurse.

In 1977, Insook’s elder sister had already been in America for five years, and Insook was going out to help look after her sister’s children.

‘I didn’t know what to expect. I was totally open, totally vulnerable.’

‘What did “America” mean?’

‘America? It was a place in novels I’d read, and films I’d seen… It was Scarlett O’Hara and Gone With The Wind. I was going to live at Tara and meet Rhett Butler, I guess… ‘

The flight itself was thrilling. Insook had a window seat; looking down on the clouds was how life was meant to be.

‘I was breaking out all over with excitement. I was totally tired, but I couldn’t sleep for a moment in case I missed something.’

It was after dark when the plane approached the coast. The sky was clear, and Insook’s first glimpse of America was a lighted city.

‘Like diamonds. Miles and miles of diamonds. I couldn’t believe it – that people could afford so much electricity! We were having to save electricity in Korea then. I knew America was a rich country, but not this rich, to squander such a precious thing as electricity… I’d never dreamed of so many lights being switched on all at once.’

The plane landed at Sea-Tac, and it wasn’t until past 2 a.m. that Insook was in possession of her green card, her ticket to becoming an American. Out in the concourse, she spotted her sister waiting for her, but her sister didn’t recognize her.

‘I was only fifteen when she left – still a kid. I was twenty now, and I’d grown. I had to persuade her I was me… ‘

Insook’s scanty luggage was put aboard the family car, and they headed for the suburbs.

‘Those huge wide roads, and huge lit-up signs… It made me feel very small… It was like being a little child again… Everything so big, so bright.’

She was describing the shock of being born.

Her sister’s house was quiet. ‘Too quiet. It was like the inside of a coffin. It wasn’t like the real world… ‘

Nor was America. Insook was astounded and frightened by the extravagance of the country in which she found herself. When she went to a McDonald’s, she wanted to take home the packaging of her hamburger and save it – it seemed criminal to simply throw it away in a litter-bin. A short walk on her first day took her from a rich neighbourhood into a poor one. ‘On this street, these Americans live like kings – and on that, they are beggars! I thought, My God, how can people live like this? How can they live with this?”’

Most immigrants were able to enjoy a few weeks, or days at least, of manic elation in the new country before depression hit them, as they woke up to the enormity of what they’d done. For Insook, the depression came at almost the same moment as she touched ground.

It would have been different if I’d come to be a student. I would have had clear goals, a programme to follow… ‘

With no programme, she sat in the vault of her sister’s house, staring listlessly at television.

‘I was terrified. I felt locked in that house for an entire year. I hated to go out. I was cut off from all my friends. I could read English, not well, but I could read it – but I couldn’t speak it… hardly a word. I felt I was blind and deaf. My self-esteem was totally gone. Totally. I was in America, but I wasn’t part of this society at all.

‘I was a huge mess of inertia. I was stopped – you know? Like a clock? I slept and slept. Sometimes I slept eighteen hours a day. I’d go to bed at night, and it would be dark again when I woke up.’

During that year, Insook’s whole family – parents, brothers, cousins – came to America by separate planes. They were scattered across the land mass, between Washington State and Detroit.

‘There was no going back. I had no home to return to. I had come here to live and I felt suicidal. That sense of homelessness… you know? You have no past – that’s been taken away from you. You have no present – you are doing nothing. Nothing. And you have no future. The pain of it – do you understand?’

Yet even at the bottom of this pit of unbeing, Insook saw one spark of tantalizing possibility. On television, and on her rare, alarmed ventures on to the streets, she watched American women with wonder.

‘Oh, but they were such marvellous creatures! I would see them working… driving cars… talking. They were so confident! Free! Carefree! Not afraid! And I was… me.’

The prospect of these women made English itself infinitely desirable. Korean was the language of patriarchy and submission; English the language of liberation and independence. Insook had school-English. It worked on paper; she could write a letter in it, even, with some difficulty, read a book. But its spoken form bore hardly any relationship at all to the English spoken on American streets. She followed the news programmes on TV (she was through with fictions), and parroted back the words as the announcers said them. She practised, haltingly, in the stores.

I said that I marvelled at her articulacy now. ‘You’re saying things with such precision, and complex, emotional things too. You’re making me feel inarticulate, and I’ve spent forty-seven years living inside this language.’

‘Oh, it is so much more easy for a Korean woman to learn than for a Korean man. She can afford to make mistakes. When a man makes a mistake, it is an affront to his masculine pride, to his great Koreanness. He is programmed to feel shame. So he learns six sentences, six grammatical forms, and sticks to them. He’s safe inside this little language; his pride is not wounded. But when a woman makes mistakes, everybody laughs. She’s “just a girl” – she’s being “cute”. So she can dare things that a man wouldn’t begin to try, for fear of making a fool of himself. I could make a fool of myself… so it was easy for me to learn English.’

It was still three years before she felt ‘comfortable’ about leaving the house, and four before she began to make her first American friends. She had gone to stay at the family house of a cousin in Bellingham, at the north end of Puget Sound, where she went to college to study for a diploma in nursing.

At Bellingham, Insook began to go on dates with American men.

‘My brothers came to see me. They felt betrayed. Korean males – you must know this – are the most conservative on this earth. For me to be seen alone in a café, talking to a white American man, that was a deep, deep insult to them. I was insulting their maleness, insulting their pride, insulting everything that ‘Korea’ meant to them. They threatened me…’

A year later, Insook announced her engagement, to an American.

‘My father said, “I will disown you”’ she smiled – a sad, complicated shrug of a smile. ‘So I said… ‘ For the first time since we’d been talking, she produced a pack of cigarettes and lit one. ‘I said, “I am sick and tired of this family. OK, disown me. Please disown me!”’

The brothers came round, with a fraternal warning.

They promised me that they would bomb the church where we were getting married. We had to hire security guards. One of my brothers said he would prefer to blow me up, blow me to pieces, than see me married to an American.’

‘And you really believed that he meant it – that he’d make a bomb?’

‘Oh, yes. My brothers weren’t doing well. They were struggling in America. They were just fighting me with what little ego they had left… ‘

The wedding went ahead, with security guards. At the last moment one of the brothers turned up, shamefaced, with a gift.

Her marriage was ‘absolutely democratic’, and it was, thought Insook, the prospect of this democracy that her father and brothers had so feared and hated. ‘For the Korean man, everything that he is, his whole being, is in direct conflict with what this society is about.’

A little Korean culture had survived in Insook’s American marriage. She and her husband left their shoes by the front door and went around the house barefoot or in stockings. They lived closer to the ground than most Americans. ‘He has a naturally floor-oriented lifestyle.’ She sometimes cooked Korean food. ‘He likes to use chopsticks.’ Her husband had ‘a few phrases’ of Korean.

‘But I seldom feel my identity as a Korean now. I forget that I look different –’

‘You think you look “different”? Look at all of us here –’ We were sitting in a booth at the Queen City Grill on First, a favourite lunch-spot for Seattle’s wine-drinking, seafood-eating, stylish middle class. We had melting-pot faces: at almost every table, you could see a mop of Swedish hair, an Anglo-Saxon mouth, an Italian tan, Chinese-grandmother eyes, a high Slav cheekbone. In this company, Insook’s appearance was in the classic American grain.

‘No, you’re right. It’s when people know I come from Korea, I sometimes get deadlocked in arguments. The moment someone knows I am a Korean, then I’m framed in their stereotype of how a Korean ought to be. Like, if I’m shy for some reason, then it’s “Of course you’re shy – that’s so Korean.” But then again, if I am outspoken, if I get angry in a discussion, that’s “being Korean” too. Whatever I do, it must be “Korean”. I do get mad over that sometimes.’

Yet Insook’s attachment to Korea still went deep. It would sometimes take her by surprise. Shopping in the Bon, she felt ‘shame’ (that most powerful of all Korean words) when she saw how Korean products were almost always shoddier than their Japanese or American counterparts.

‘They are made to fall apart in a few months, and I think, this is my country –’

‘But your country is America now.’

‘No, I still identify with Korea. I do still think of myself as a foreigner and of America as a foreign country. Not on the surface. In a profound way, that I can’t change. I think, too, that my sense of root is beginning to return. Just lately, I’ve been taking up calligraphy again… And I’d like to do something for the Korean community here. When I see other Koreans in Seattle, I know that we’ve all been through the same pain, the same suffering, and I feel good that I went through that pain… it’s very important for me.’

She was doing what she could. For Korean patients in the hospital where she worked, she was translator, legal advisor, counsellor, kind heart. That morning, she had been trying to find a lawyer who would take on the case of a Korean who had been injured at work and whose employer had refused to pay him compensation.

‘But I do feel uncomfortable with other Korean people. There’s so much suspicion and resentment. To so many of them, I am not me, I am a girl who married an American. As soon as I tell them my American name, I see it in their eyes. I am one of those.’

‘But you still go on trying –’

‘I feel compulsion – compulsion? compassion? I don’t know, I suppose both for Korea. You know? It’s like having two friends… There is the rich friend, who’s doing very well in life. You’re always glad to see him; you’re happy in his company… But you don’t need to worry about him. That’s like America is for me. Then I have this poor friend. Always in some kind of trouble. It depresses me to have to meet him. But… he is the friend who needs me. That is Korea.’

Some days later, I was talking to Jay Park again. A year after he’d arrived in Seattle, he’d met a Korean girl (at the Presbyterian Church), and they’d married in ’67, driving off in the pale blue T-Bird with electric windows. They now had two sons and a daughter.

It was odd, Jay Park said, that while nearly all of his sons’ friends were Korean, ’80 per cent’ of his daughter’s friends were American. ‘She just seem to like to hang out with white Americans… ‘

I could hear Insook’s voice, talking of ‘marvellous creatures’.

‘How do you take to the idea of a white American son-in-law?’ I asked.

Jay Park laughed. ‘I deal with that one awready. I tell her. “Day you bring home American boyfriend, that’s the day you dead meat, girl!”‘

It was a joke. He was hamming the role of heavy Korean father, but there was enough seriousness in it to give it an uncomfortable edge.

‘Dead meat!’ His laugh faded into a deep frown. ‘I see these intermarriage families, and always is some… unsatisfied… life. You get what I am saying now? I am thinking our kids got lost somewhere… somewhere between the cultures.’

Photograph © University of Washington Libraries