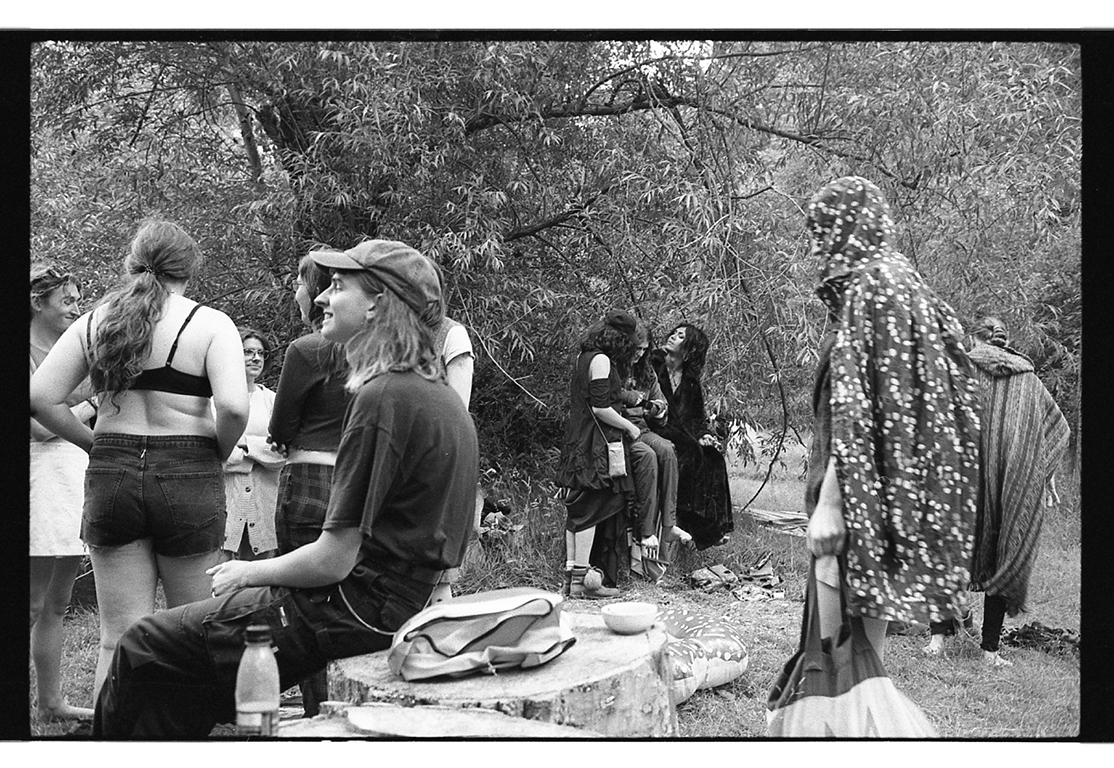

The camera slips from place to place, fuzzy yet alert. He tells me, afterwards, that the photographs were taken over three or four days. I knew that it was days, not hours. But it could have been months. In this series of images, taken over the course of two summers in Leighton Buzzard at Camp Trans, time neither passes nor stills; it pauses just long enough for outlines and surfaces to thicken, like butter creamed with sugar.

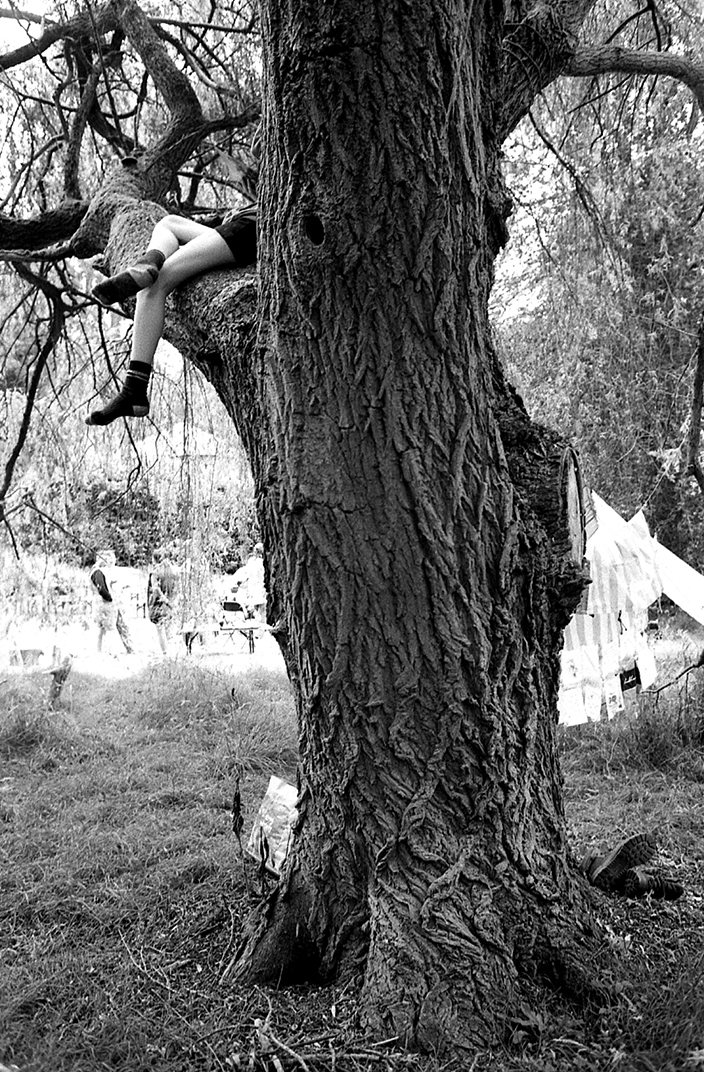

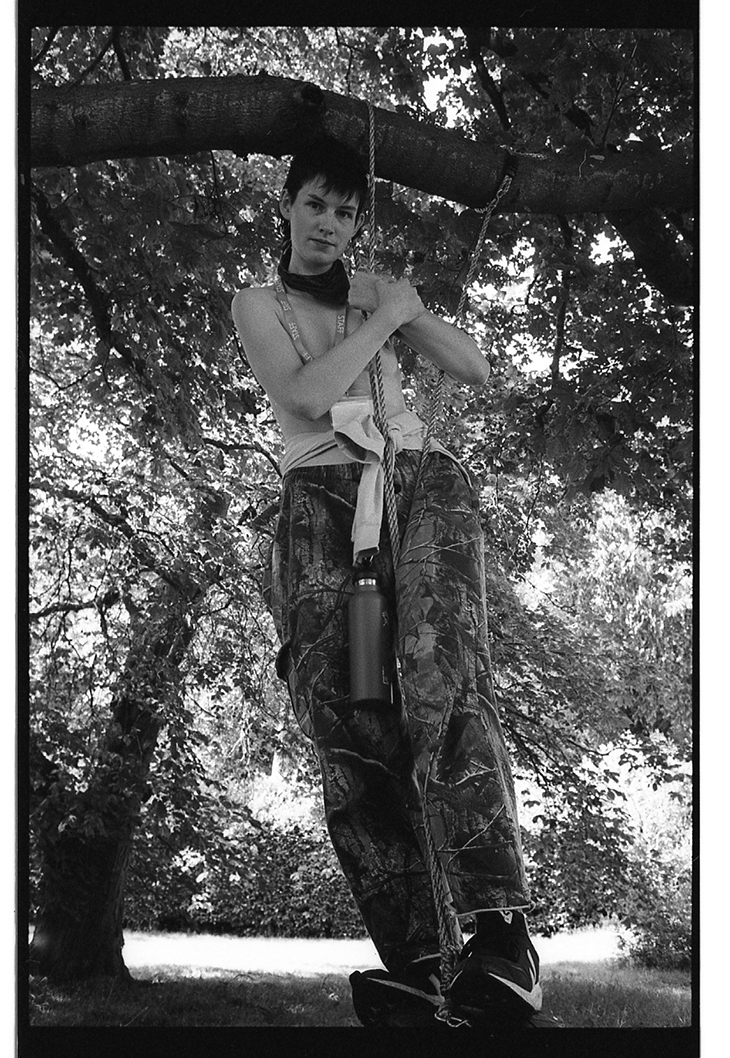

Greyscale, a thick tree forks in two. More branches sprout from the trunk, slimmer, more pliant: legs, at a jaunty angle. Shoes hummock at the base. Gigantic, entwined roots are companionable and climbable. The image has a freeing effect. I feel lighter. Being at home with nature appears desirable, but the promise is fraught for viewers familiar with Western art, where ‘the pastoral’ implies a paradise lost.

Words like ‘filament’ and ‘filial’ come to mind as I contemplate the limbs, all the limbs, the branches, and the shining phantom-people. I think of how Francis Ponge describes vegetation as rooted in his poem ‘Faune et Flore’ (1942): he sees trees expressing themselves by means of gesture and proliferation, because they cannot pick up and move. This is not the case here. The trees are animate, ready to play. A quick and birdlike glee is somewhere in the past, present, future of each image. A clamber, a lift, a jump, a lean, a roll – enjoyed, imagined; not ‘captured’.

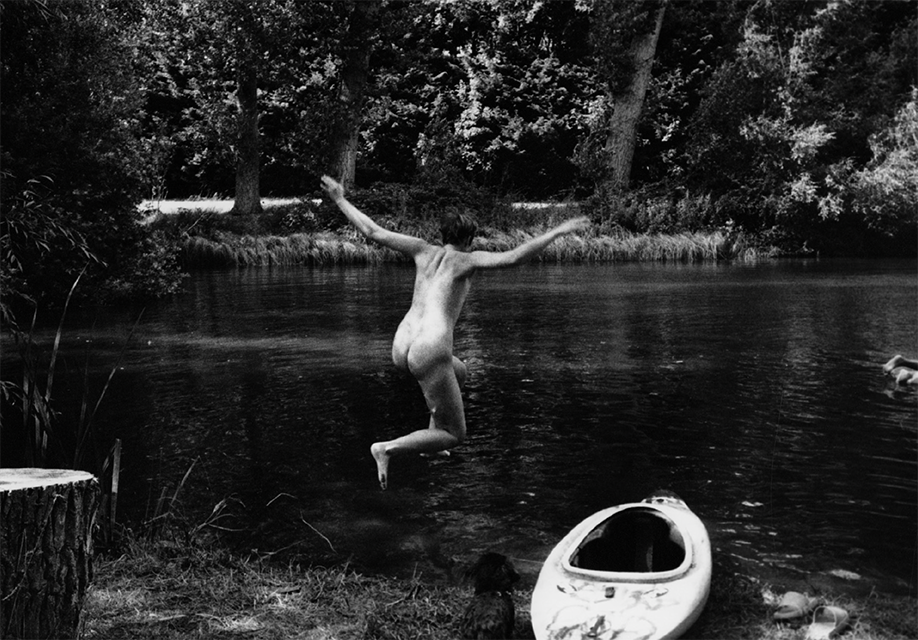

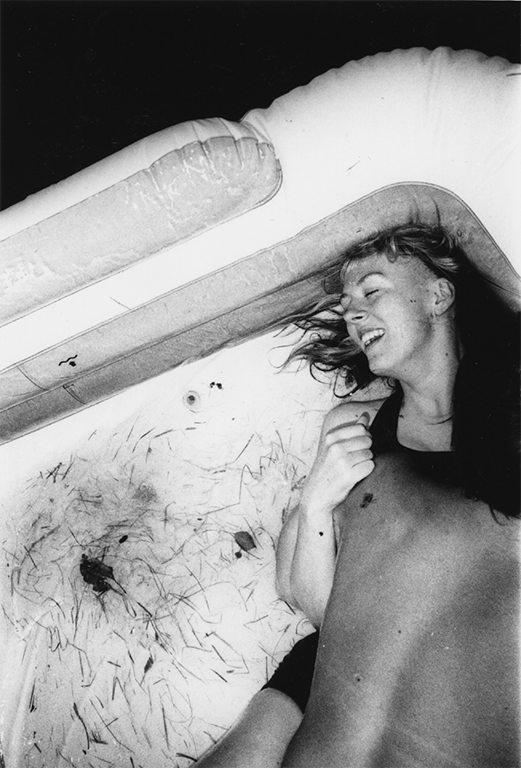

Move how you feel moved to move. No limit; also, no hurry. Camp Trans breathes an atmosphere of rest, like a treasured painting in a peaceful gallery. Some bodies are partly or wholly unclad. People meet the camera and there is no hardness, nothing posed, an absence of startlement. The invisible artist who invites us to stand beside him is clearly among friends; being kind, being of a kind; witnessing with-ness.

The flesh is like grass, brushing up against other soft blades. The sunlight and the shadows of leaves bring a glisten to tanned skin and darkness to paler skin, so that bodies partake of light more than of complexion; they are alike in dapple and dazzle.

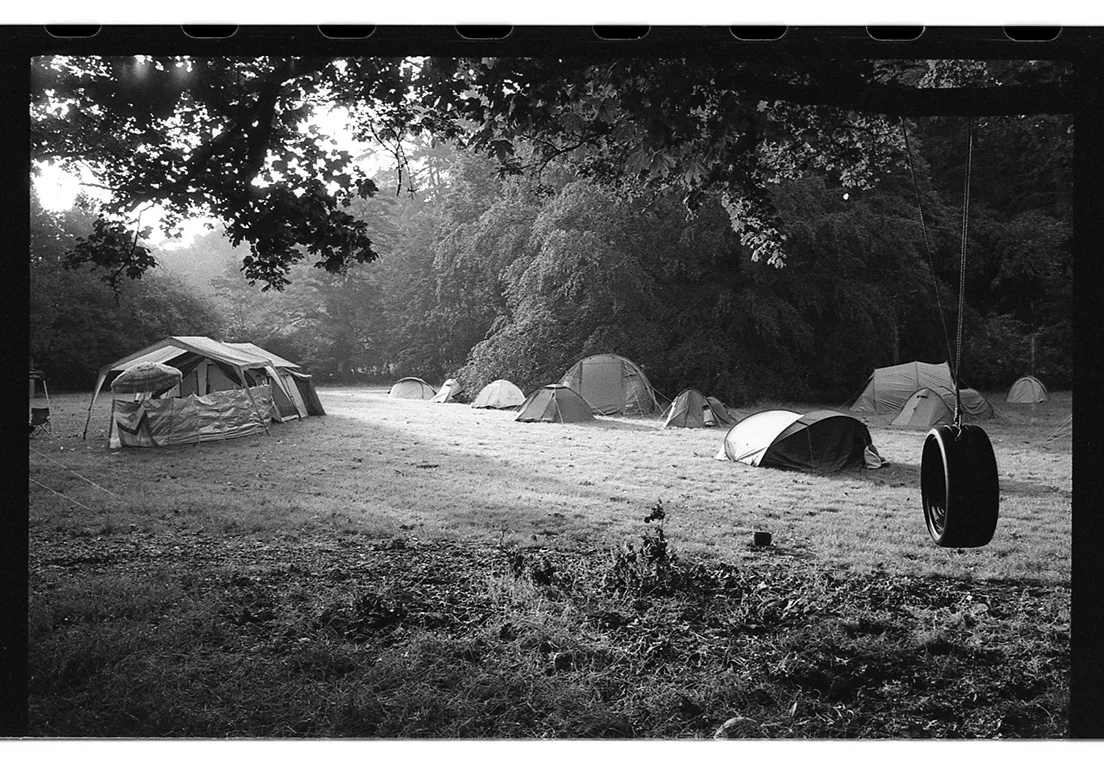

Our gaze becomes tender. We can trust the focus of the photographs, which leads away from the effort to look, into seeing, and stillness; into seeing stillness. For a few days in life, we drift from sight into a sense of cocooning or spooning. A nude body is waterbird, a torso fruits in the tree. I want kindness to hatch our species-renewal, in the curves of these dormant volcano tents.