Because I am unable to hear a song without listening attentively to the lyrics, I tend not to play music with words while I write, at least not during daytime.

Or any good music, for that matter, because I am incapable of hearing without listening. There is such a thing as ‘background music’ of course: ubiquitous, and I despise it. But good music cannot be played as background, or on headphones while about our quotidian lives – why defile Mozart or Leonard Cohen by turning them into a soundtrack to ‘signal failure’ on the hideous London tube, or – as the other day – ‘national system failure’ on our non-railway non-network? The Rolling Stones, maybe, thrash and death metal – they’d suit well. And if you like stupid music, as many people do, then it does not matter-in fact, stupid music is just right for a stupid world.

But if you love real music, do not play your favourites while out in all that ugliness, or while working. It deserves more respect than that. Keep it for a drive through the desert or forest, intimacy at night, or just quiet reflection.

However, there comes a time. I write like this: a version written sober, until about 19.00. Then, on a rare good day, I make a copy, fuck it up and freewheel with Roget’s Thesaurus and a bottle of wine at my elbow. The best version is a cross between the twain, sober and drunk, welded next morning. That second phase does need music. Here’s the top eight, plus a crucial bonus track, the post-scriptum to my life.

B.B. King: There Must Be a Better World Out There

B.B. King was the last great bluesman, not just musically but in that he was the last to be able to say he was the great-grandson of slaves, and that he himself followed a mule and hoe through the cotton fields of Mississippi as an orphan, aged nine. For the book, I conducted what turned out to be the last interview B.B. gave before he died in 2015. Over that same one afternoon and evening, I heard him play two sets – in a park, then at a juke joint through the slats of which he used to peep as a boy – in his home town of Indianola, Miss.

The blues was the first music I knew and loved: listening – if home from school, ill – to my mother play Billie Holiday, Bessie Smith and Edith Piaf while she worked. I listen too, to all three. The blues are descended from the slave holler, and as such are a cry of pain – but also of defiance, and the promise of a better life to come after this one, of tribulation, struggle and suffering.

I want that day and night in Indianola to be among the last things I recall before I go. After that, I’m not sure I believe there is a better world somewhere, but I hope there is and if so, B.B.’s there for sure, playing his famous ‘butterfly’ tremolo on a guitar by the name of Lucille, with which he could say so much more than any of the words I write – or that anyone else writes for that matter.

Jimi Hendrix: Machine Gun

(Live: Isle of Wight)

I was born on the London street where Jimi Hendrix died. Lansdowne Crescent, Notting Hill (when it was Notting Hill), W11. I came into the world at no. 44 in 1954, Jimi left it at no. 22 on 18 September 1970. Eighteen days before his death, I’d seen him play at the Isle of Wight festival, sitting right at the front, aghast at it all, but above all at his account of ‘Machine Gun’.

This was a time of war in Vietnam and a wave of outrage, a peace movement against that war and all war, was propelled by music. ‘Machine Gun’ is the soundtrack to that movement: a depiction of war and the pity of war, a pastiche of the leaden sound of war, and a searing cry on guitar against its madness and carnage. The Holberg Prize-winning writer Paul Gilroy argues that it is important to see Hendrix as a former soldier who turned his back on the military for peace – which is who he was and what he did. He did not know warfare at the time of that concert, nor did I. But I do now, too damned well for my own good, and I wish I didn’t. Take it from me, ‘Machine Gun’ is the peace movement’s anthem, on every level.

Hendrix was all about transgression. He was part African American, part Native American, influenced above all by the blues and Bob Dylan, famously described as too white for Harlem and too black for Greenwich Village. He also blasted through the wall that absurdly divides ‘rock’ and ‘classical’. Patti Smith recalls a conversation shortly before Hendrix’s Isle of Wight concert and subsequent death, when he told her his next music would be ‘something else, like with Handel and Bach and Muddy Waters and Flamenco’. He has described his apartment in London as ‘the only home I ever had’, and for the book I interviewed the woman with whom he shared it, Kathy Etchingham. It happened to be the house previously occupied by Georg Frederic Handel, and when Hendrix learned this, he hastened to HMV to buy The Messiah and Belshazzar. She describes him sitting on the bed, jamming along to the records. Sadly no bootleg, but if there had been, it’d be on this list.

Grateful Dead: Fire On the Mountain

(Live – if poss. from Dick’s Picks, Vol. 6, Hartford Connecticut, 1983)

There is no musical institution equivalent to the Grateful Dead. A rock band, yes and no; jazz band, yes and no; contemporary ‘classical’ music, yes and no. They are just the Dead; like the Beatles in British music, they stand apart, unique. Like Coltrane, they can play the same music over and over again, but never the same, and if one gets it, one can never get tired of it. There are people who listen only to the Dead, who have travelled for decades to see them play hundreds of times.

The Dead never really exported beyond America; they grow from American soil. But there was a coterie of ‘Deadheads’ in the UK when I was young, and we drove a Volkswagen microbus around Europe called ‘Pigpen’, named after the singer who was alone in the band in shunning drugs, only to die of drink in 1973.

When the Dead played Bickershaw, Lancashire, in 1972, there we were. Likewise Alexandra Palace two years later. When they played the Rainbow Theatre at Finsbury Park in 1981, I took the girl to whom I was engaged, who hated them. I must have loved her very much, as I agreed to leave half way through, during the customary ‘Drums’ and ‘Space’ (I should have read the tea leaves and stayed!). Soon after, I finally got to see Jerry Garcia on home turf, at Salinas, California – fans arriving to do ‘touch circles’ (which I enjoyed observing but in which I declined to participate) hours before the gig. I saw the Dead again, in America – by sheer co-incidence in the same town – seven years later. And with Garcia dead, gratefully or otherwise, when the splinter ‘Live Dead ‘69’ came to Frome, Somerset, in 2017 to play the album of that name to an audience of eleven, my lady and I accounted for two-elevenths of that crowd. When rhythm guitarist Bob Weir and percussionists Kreutzmann and Hart played the Hollywood Bowl just last month, June 2019, as ‘Dead and Co.’ we bought flights and were there.

What is all this? Yes, to a degree, it’s a ‘cult’. For the book, I interviewed Bob Weir, sitting cross-legged on the floor of his home, surrounded by wondrous guitars, and he spat his anger at ‘that notion that we’re up to more than we actually are’. The only other artist to whom this had happened was Dylan, he said. Yes, it’s about drugs, but I would not know about that – I never trusted myself enough to take LSD.

But what the Dead are about, above all, is improvisation and all it entails and means. The liberty to make every performance different through the sheer delight of experiment, though clairvoyant understanding between the musicians, but within the confines of absolute artisan mastery of the craft, the instruments, and dedication to the original song, like that of a sculptor to clay.

I choose ‘Fire on the Mountain’ because it is the song that I remember most vividly, spellbound, from the Garcia concert in Salinas – a sublimity in sound, lucid precision on the guitar, but free, somehow, to fly. And because I listen to it all the time for Weir’s rhythm guitar, finally explained on a film, when he said that he took his ideas for chords from listening to McCoy Tyner accompany Coltrane on keyboards. It’s there. The Dead, unclassifiable, as great music should be.

Patti Smith: Waiting Underground

Music is about, among other things, sonority: the indefinable quality of a sound. Patti Smith has a voice of singularly expressive sonority, and works (at her best) with musicians who can play to it. Hers would be ‘pure’ rock and roll, were it not for the fact that she is also an accomplished poet, so that as with Dylan and Leonard Cohen, the poems become lyrics and we cannot be sure what the difference is, or when a ‘poem’ becomes a ‘song’ and vice-versa.

I had the honour of spending an evening with Patti Smith, thanks to mutual friends, during my New York years and troubled times, in that period between the attacks of 11 September 2001 and the invasion of Iraq. She gave two intimate concerts at the Bowery Ballroom at the close of each year, one on her birthday, December 30, and the second on New Year’s Eve. Those concerts of 2001 and 2002 were like séances of like minds in the awful limbo between 9/11 and war. And there is something about this song, its menace, the loss of hope but promise of gathering in the lyrics, but above all its sonority – both vocal and instrumental – that captures the purgatory of that time in America, pregnant with catastrophe.

In summer 2003, the invasion of Iraq done but the war never over – not even to this day – Patti Smith came to London and played on my eldest daughter’s ninth birthday. We went together – it was Elsa’s first ever gig – and after the show, Patti gave her the ribbon from her hair, saying: ‘Welcome to rock and roll’. I think of that moment every time I play this song, its joyful memory in counterpoint to the pain – but also in harmony with the promise – of which the song speaks:

If you believe all your hope is gone

Down the drain of your humankind

The time has arrived

You’ll be waiting here as I was

In a snow-white shroud

Waiting underground

Joan Baez: Deportee

Joan Baez was my first love and she’ll be my last. Like most serious teenagers of my age, I adored her when I was sixteen in 1971, and went to Chicago for a formative summer. I was an usher at a benefit concert she gave for a Quaker draft resistance effort, wearing a T-shirt with a rifle being broken and the words: ‘Usher in Peace’. During the interval between sets, a man asked me, casually, to ‘go fetch Joan to say hi to some disabled vets’ assembled in the foyer. What, me? I panicked, but pretended to be efficient, followed his directions and knocked on her door. ‘C’mon in!’ said a voice. I pushed the door, and there she was, breast-feeding her infant son, Gabriel. I mumbled something. ‘Darn it, I forgot!’ She flashed a smile, passing the baby to a lady, ‘don’t tell!’. I led her to the foyer, knees weak, heart pounding; hey, just another chore in the life of an usher. Fifteen years later, while I was interviewing her, Joan Baez signed an album for me: ‘Usher in Peace, is it?’

She was marvellous in 1971, but nothing like the five times I heard her sing during 2018–9, in London and Paris. As beautiful as ever, voice better than ever, darker and deeper. Why should not singers, like painters, improve with age? It occurred: no one, no one, has walked a straight line quite like Joan Baez. Unswerving and unwavering, for peace, against war, for justice, against oppression. Most of us skid, some of us despair – I did, gave up on all my ‘isms’ (apart from vegetarianism). But even nihilism and cynicism didn’t work, there has to be something. And that something is in the songs and career of Joan Baez.

I’ve worked a lot recently along the US–Mexican border, with its tribulations, bloodletting, occult shadows and bright colours. And the kernel of those recent concerts was a song written by Woody Guthrie in 1948, about Mexicans working and dying in the deserts of America. She sang it in 1971, and she sings it now.

Not only all that, but Joan Baez is also funny. Backstage earlier this year, I remarked that she had omitted ‘We Shall Overcome’ from the set lists. ‘Because we were overwhelmed’, she replied, with that same smile.

John Cale: Half Past France.

After a terrible accident in 2013 (I tell strangers I fell five metres from a wall, but actually I jumped) and during the two years of pain and morphine that ensued, I revisited the music of John Cale, both with the Velvet Underground, for which he is most famous, but more interestingly and interested, his better and more adventurous work since.

I met Cale in New York soon after the attacks of 11 September 2001; only a musician could have an aural memory of that occasion: ‘I went down to the street door, and watched crowds rushing past in flight. Hundreds of people whose feet made no sound at all on the street, the dust was so thick. A stampede, in almost-silence.’

At the time, I found the wry, often nihilist ennui of the Velvets, and subsequently Cale – their diagonal glance across the idealistic 1960s – jarring, albeit tempting. With time, though, I think they were perceptive and justified. Cale is the master of the drone, primal music that measures and defies time by detachment from it, and at one concert at the Barbican Theatre in 2014, he and his band amplified the music not from the stage, but from drones flying above the audience.

This song is from one of Cale’s finest albums, ‘Paris 1919’ – intended, with success, to capture not the landscape of Europe after the Treaty of Versailles, but the feel of no-man’s land during and after the slaughter of World War One, and an exhausted ennui in this purgatory. But there is no limbo as pleasurable as a long train ride (across Europe, not the UK!) and I would hum and sing this song to myself as I take either the night train – as we used to – or the daytime TGV from Paris to Milan, rarely happier, between places, half past vast France, going by outside the window. The song is in a no-man’s land both geographically, and existentially, even emotionally: ‘I suppose I’m glad I’m on this train.’ Unnerving, but not unpleasant.

Cale is restless innovation, every time, and I have heard scores of versions of this song in concert: fully orchestrated for a homecoming in Cardiff and at the Royal Festival Hall, as a mighty electronic symphony at the Barbican that night, and elsewhere; shattered into shards, deconstructed and reconstructed at the Brooklyn Academy of Music.

This song is the music of endless time, an infinite Waiting For Godot. I asked Cale, for the book, what were the politics of the drone. He answered: ‘It’s about the power of music, and about human fragility. It’s like that stone in your shoe. It’s about how long you can keep going with that stone in your shoe. Keep going long enough, and you’ll find out in the end.’

Lila Downs: Paloma Negra (The Black Dove)

My life is replete with regrets, one of them being that I came too late to Latin America, and to the country which has captured my heart, Mexico. I don’t know why. But I do know why I became hooked, once I began learning Spanish and looking hard, I felt Mexico and, as importantly, the Mexicans.

One must be careful not to resort to romantic cliché, or some kind of Latin ‘Orientalism’. But the history and legend – Maya and Aztec lore – cut deep and infused the mysterious present. More immediately there is this: that strange point of contact between suffering and alegría among Mexicans, and the defiant passion that results from the collision. In Mexico, the darker the occult shadows fall, the brighter the colours. As the country battles its poverty, migrant tribulations and drug wars, nowhere is addictive like Mexico for that ready smile, unnecessary chat or that look right in the eye.

All that is all here, in ‘Paloma Negra’ and Lila Down’s beauty and voice. (It is also a flagship in that current dynamic whereby English ceases to be the lingua franca of popular music, and never was that of traditional folk.) Lila Downs sings both ancient and modern, pain and beauty: Arrancarme ya los clavos / De mi pena / Pero mis ojos / Se mueren / Sin mirar tus ojos. As though craving for the black dove, a lost lover, was also that for something huge, in a country that superimposes Catholic devotion like a thin veil onto the deeper, pagan primordial.

Downs’ shattering voice holds that note with the uncanny mystery of all this and her country; beauty-and-grief, power-and-passion, never knowing where the note, or the song, will end, nor whether it is a lament or cry of resolution; never knowing where the bottom is, where the obsidian-black sun shines opaquely over the underworld. Listen, and you’ll get an idea . . . No more, no less.

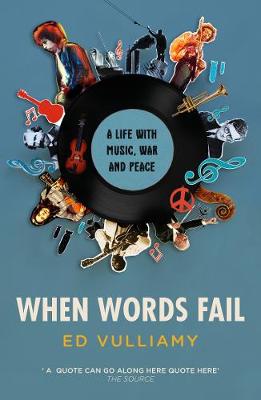

Crosby Stills and Nash: Long Time Gone

At the core of my book, When Words Fail, is the connection between music and the real world, and above all the world as forged by the catastrophe of humankind: music in politics, music in war and against war, music for peace. The ethos of the best music that drove the 1960s was yearning for a better world, and a cry of outrage against war. ‘Long Time Gone’, sung by the best trio of voices ever to sing three-part-harmony in rock music – Crosby Stills and Nash – epitomises that yearning not just in its lyrics, but in every pore of its sound: the pounding keyboard and bass, the break on guitar: an impatient entwinement of rage and hope. ‘Long Time Gone’ has musical willpower unlike any other song I know.

Of all the famous musicians who helped with the book, none did so with quite the enthusiasm and generosity with his time as Graham Nash. A superstar, Nash didn’t have to do this. But together we poured over the theme of what music does and why – best expressed by Nash when he recalled sitting behind the Beatles at a Jimi Hendrix concert in London and thinking: ‘What on earth is going on?’ What indeed – that became a chapter heading on the essence of music. And we did this in Paris, after two concerts Nash played just before and soon after the attack by ISIS killers at the Bataclan Theatre.

It would be precocious for any book about music to have a conclusion, but how, then, should I end it? After five more hours of discourse – now in New York, Nash and I hadn’t actually cracked the initial question – what on earth is going on, with music? Graham said: ‘Tell you what, are you free tomorrow? Do you want to come back, and we can talk a bit more and . . .’

There is a particular, further, reason for choosing this song. When I heard Crosby Stills and Nash play in London, then Paris on the eve of the Bataclan attack, the second lead guitarist behind Stephen Stills played with a remarkable range of sonorities, adapting to each number as the best session musicians do, but adapting them also to his own sound, driving and infusing every song with his own creative edge. As it turned out, I’d been at school with this marvellous musician – Mick Barakan, stage name Shane Fontayne; he’d gone from playing with us lot during lunch hour gigs in a cellar to playing with, and becoming, one of the very best. Here they are, estimably recently and still proclaiming the song, Mick/Shane at the back, behind Croz, wearing khaki – wheel of a long life come full circle:

Bob Dylan: Mr Tambourine Man

(For good measure: a funeral march)

You can play this at my funeral. It’s my favourite song of all, by the master of song. It describes a visionary world I’ve yearned for and aspired to since I first heard this aged twelve – and on which I’ve now, reluctantly, given up. The lyrics shimmer and swirl, music in themselves, describing a state of unfettered devil-may-care existential freedom and readiness to ‘go anywhere’. Now an Ancient Mariner, terrified of ‘settling down’, I wear a tattoo of Gustave Moreau’s Ange Voyageur on my forearm, and wonder whether the angel wanders itself or accompanies those who do – perhaps both. Whichever: Mr Tambourine Man is that angel, and this song is like Moreau’s painting set to music. If there was any daft debate over whether Mr Zimmerman was a worthy Nobel laureate, listen carefully to the last stanza, ‘Out to the windy beach / Far beyond the twisted reach / Of crazy sorrow . . .’ I’ve been trying to get to that beach all my life – and have yet to make it.

I never interviewed Bob Dylan, but in 1987, my news editor at the Guardian kindly assigned me, knowing my partiality, to cover the London launch of a ghastly film in which he was co-starring. There was a photo-op by the river, and I happened to have my copy of ‘Bringing It All Back Home’ (on which Mr Tambourine Man features) with me, and a pen. Clutching them, I charged across the space between Bob and the cameras, and asked him to sign my album. ‘This is supposed to be for journalists’, he mumbled from behind sunglasses. I am a journalist, I replied. ‘You don’t look like a journalist,’ he said; it was the biggest compliment I’ve ever been paid.

I try to sing this song, and a live rendering has become rather a good way to end events at book festivals talking about When Words Fail. Why talk about music, rather than sing it? It can go horribly wrong, but never in Ireland, where everyone can sing in tune. Here’s what happened at the Borris Festival in Co. Carlow recently, after the best moderating of all by marvellous Fiachna Ó Braonáin, no less, of The Hothouse Flowers. (I am mortified about screwing up the ‘ragged clown’ line and omitting the ‘windy beach’):

You can listen to Ed Vulliamy’s playlist on Spotify: