Eighth Beginning

When they placed the child on Anna’s breast after the birth, she felt nothing.

‘Congratulations,’ said a mouth. Hands washed themselves.

The child looked up at her with big eyes.

A white noise enveloped her like a woolly mitten.

Even though she was lying with the child on her chest, she now saw him back in the arms of the midwife, who quickly began unwrapping the umbilical cord from around his neck.

‘Why isn’t he crying?’ Anna asked, and the placenta was delivered, another doctor summoned, and then another doctor, and another, all concentrating on her injuries.

‘Why isn’t he crying?’ she asked from within the white noise.

The midwife unwrapped the umbilical cord. Finally he cried. Anna lifted a hand, black with mucus, and regarded it. ‘Meconium has passed.’

‘Is that shit?’ said Anna.

They took him away and moved her onto a bed in the corner. The whooshing grew louder. Far away, the infant was examined.

‘Aksel, what are they doing? Tell me what they’re doing.’ ‘They’re counting his fingers and toes,’ said Aksel reassuringly. ‘There are ten of each.’

The doctors finished and disappeared.

Aksel took off his shirt and lifted the newborn child up to his bare chest. They lay down on the bed where Anna had given birth, all signs of the labour already washed away. A fresh paper sheet rustled beneath them.

It was at the sight of the child against the man’s stomach, the love that seemed to exist between them already, the pride in Aksel’s face as he gazed down at the boy, the happiness she saw but did not share, that the whooshing sound went from encasing Anna to penetrating her.

Aksel stood up gingerly with the child in his arms and went out into the hallway. Anna was lying by the window. She couldn’t move. She assumed she had been forgotten.

A new midwife came in and placed the child at Anna’s breast, but he wouldn’t latch.

‘I need to talk to a psychologist,’ Anna rasped.

‘There’s a priest,’ said the midwife. Her face was so big and close to Anna’s, then it was gone.

They were transferred to a different room. Aksel carried the child while Anna was supported by the midwife and a nurse. She was told not to sit down for the next six weeks due to the tearing. All Anna could think of was the white noise. She could not speak.

That the child had left her body and now existed outside the deafening whoosh that was Anna caused an afterpain to course through her. She wanted to ask if she could hold him, but the words didn’t come.

That night they tried many times to get the child to latch, he had swallowed amniotic fluid and couldn’t suck.

As soon as the midwife concluded that the latest lactation attempt had failed, Aksel would take the child. Anna was so weak she could hardly lift the boy. She only had the chance to hold him for a few minutes at a time.

Then a pump was rolled in on a stand with wheels, and Anna sat through the pumping every three hours. All the darkness was sucked out through a tube, and yet there was always more.

At two o’clock in the morning, the midwife on duty ordered Aksel to get some sleep, and they rolled in a bed for him. Anna couldn’t sleep.The child began to cry. She couldn’t get out of bed. A new midwife came in.

‘Why don’t I give him some formula?’ she asked.

‘No,’ said Anna, remembering her mother’s warning that the bottle could ruin breastfeeding altogether.

‘Has the milk come in?’ the midwife asked, nodding at Anna’s breasts.

‘Not yet.’

The scene repeated itself throughout the night. The midwife returned and said, ‘You need to get some sleep. Have you slept since giving birth?’

‘No,’ said Anna. The child cried, Aksel slept, she rocked the cot from her bed.

‘Can’t I give him some formula?’ said the midwife. ‘No,’ said Anna.

‘Has the milk come in?’ ‘Not yet,’ said Anna.

The night and the child’s cries intertwined into a rope that tore through her, pulling tiny parts of her with it and carrying them away. Yet there was always more. The door opened.

‘Aren’t you asleep yet?’ ‘No.’

The child cried.

‘May I give him some formula?’ Anna said nothing.

Carefully, the midwife approached the cot. She looked over at Anna. Their eyes met. She gently carried the child away. Anna could hear him crying further down the hall. Then he stopped. She stared out into the dark. The room was dimly lit by the lights in the windows of the hospital’s opposite wing. Anna pulled the cord by her bed and heard a buzzer go off downstairs at the nurses’ station. It took a long time for someone to come.

‘I can’t sleep,’ said Anna when a nurse tiptoed in.

‘Have you still not slept since giving birth?’ asked the nurse. ‘No,’ said Anna, ‘could I get a sedative?’

‘Are you sure?’ ‘Yes,’ said Anna.

The nurse left. It took a long time for someone to come.

They think I’ll fall asleep on my own, she thought. They didn’t know her. The night was very long.

After a while, the midwife wheeled the sleeping child into the room in a plexiglass cot.

‘Could I get a sedative, please?’ asked Anna.

‘Have you still not slept since giving birth?’ asked the midwife. ‘No,’ said Anna, ‘I can’t sleep.’

The midwife left. After what felt like an eternity she returned with a little white pill.

‘I took these when I was pregnant,’ said Anna, ‘they’re not strong enough, I need two.’

‘Just start with one for now,’ said the midwife. The child was sleeping. Aksel was sleeping. Anna took the pill. The hospital was quiet. Occasionally, the sound of a buzzer from one of the other rooms where someone was calling for help.

Aksel stirred in his bed, it was early morning. Anna pulled the cord again.

‘Could I get another sedative?’ she asked. ‘One pill isn’t enough.’

‘Have you still not slept since giving birth?’ asked a new woman who had just begun her shift.

‘She needs two pills,’ said Aksel, who had woken up and was lifting the child out of the cot.

The woman left the room and came back with one more pill. The round, white shape of the pill in the woman’s hand sank into Anna like something from a dream.

The woman gave the pill to Aksel, who handed it to Anna. He placed a glass of water on the chair by her bed. She looked at the child in his arms. Red and wrinkly. She took the pill and swallowed. As the room brightened and the awakening patients murmured in the hall, Anna let herself fall deep down into the ground, to sleep.

Ninth Beginning

Dear

Nothing reminds me more of writing than doing laundry. My thoughts come together in a similar way. I do it while the others are sleeping. It’s a pleasant loneliness. I think of all the women who have stood here before me, carrying out these same movements. Each time I lift the clothes from the basket and up to the line, I feel these women throughout hundreds of years passing on their stories through me. Time flows through me. I feel their temperaments. This inner place to which work takes you, and where no one can follow. And I feel how, here, by the clothes line, I become invisible to the world but clear to myself.

Everyone has their own system, order and pattern, rules for how each item is to be hung and folded. Once dry, I always take down the child’s clothes first, then my husband’s, and finally my own. I always have to fold everything right away, I can’t stand things getting wrinkled. That’s one of the reasons I try to keep my husband from doing the laundry. It always turns out wrong, and he leaves the clothes inside out when returning them to the laundry basket.

I’m leaving you my papers in the hopes that you will find order where I could not.

Yours

A N N A

Tenth Beginning

The night Anna and Aksel came home from the hospital, they put the boy to sleep in a little wicker bassinet, an heirloom they would soon replace with a hanging cradle.

The child slept, and maybe Anna had just nursed him, or she was awake like always, or maybe she had woken up with a start in the middle of the night. Whatever the case, Anna lay awake in the night, convinced that if she did not actively remember to inhale and exhale, she would stop breathing and die.

She woke up Aksel. He saw her shaking. Aksel seemed to be outside the dome of reality in which she was confined to breathing air in and blowing it out so that she would not die. He was faceless in the dark. Where was the boy? There was a narrow built-in cupboard above the radiator. The cupboard came towards her. Inside the cupboard the child’s clothes lay in neat stacks. There was orange yarn and a bib with mint-green four-leaf clovers. There was a wire basket she planned to use for socks, and in this basket lay a little ziplock bag with two pills. Two round, white pills with a groove down the middle so they could be broken in half, white pills, eyes, the doctor’s hand giving them to her. In case you feel anxious at home, he said. It’s important that you get your sleep. They repeated this to Aksel several times. Later, years later, Anna believed Aksel had forgotten what the doctors had told him: for Anna, sleep was not the same as for other people. That if Anna did not sleep, it could kill her. The two pills were sedatives. Why didn’t Aksel remember what the doctors had told him? Should Anna remind him? It was shameful to ask. Still, she reminded him over and over. She hated him for forgetting. She started to suspect that he did remember the doctor’s counsel, but that his love for Anna had faded over the years, and so too his concern for her sleep. Other times, it was as though he couldn’t bear the worry. That Anna’s sleeplessness was too hard, and he was angry at her because of it. That he saw it as a problem he had to solve. If only she would exercise more, eat more healthily, go to bed earlier. But no habits could change Anna. That was what Aksel didn’t understand. The parts of her he didn’t want to see grew bigger the less he wanted to look at them.

At night, the two pills in the cupboard, the cupboard which at this moment transferred its soul to Anna and rebuilt itself inside her, with the baby clothes and the darkness, the wire basket with the pills at the bottom. As I write this, several years later, the cupboard that entered Anna that night is still inside her, and she loves the cupboard as if it were a child. That other child who slid out of her in the delivery room, the child she had loved while it was inside her belly, a whole other child than the one who came out of her. That child was now a cupboard, and the cupboard lived inside Anna.

‘Should I take a pill?’ Anna asked Aksel in the roar of the darkness no one could hear but which rose and fell inside her.

‘Yes, good idea.’

She got up and took out the wire basket from the cupboard. ‘You put them there?’ Aksel asked.

Anna stared at the pill in her hand. The whole room turned into a funnel with the pill at the bottom, pulling her towards it. She swallowed it and climbed back into bed. The responsibility she had to take for herself, for life being insufferable in that moment, it was almost too much to bear. Aksel, who was turned towards the child, patted her on the shoulder and fell asleep. Night was there.

Eleventh Beginning

Date: 2 years and 5 months after the birth

I asked myself why I no longer dreamt. Then I realised it was because the child’s crying woke me so often throughout the night I could never recall the dreaming part of sleep.

He was two and a half and still didn’t sleep through the night. Perhaps due to our inadequacy as parents. Perhaps merely a coincidence, an inalterable circumstance, like the weather.

In any case, I no longer dreamt. I suffered from a dream deficiency. When the child was born (or perhaps it happened stealthily during the pregnancy, like a brewing storm), life was divided into separate entities that had to fight amongst themselves for the right to exist. The child, the mother, the partner, the father, the woman, the family, the couple, the individual, the writing, the housekeeping, the work.

It was unclear to me what my task was. I was charged with a duty of the utmost importance, but when I rolled up my sleeves and got to work, my hands plunged into an enormous shadow and I could no longer see them.

How to live in such a divide? Cut off from oneself and from love. How to connect these murky worlds?

Twelfth Beginning

I want to write a normal book, wrote Anna. Did this longing for normalcy come with giving birth to the child? This longing to be readily accessible like a breast filled with milk.

When I got pregnant, wrote Anna, I became obsessed with averageness. I wanted to give birth to an average child. Of an average height and weight. With an average number of fingers and toes. This was how I would protect the child against death. I wanted an average pregnancy, with an average weight gain, the average circumference around my belly, the norm, a normal body. The child’s viability and strength.

This is my book, wrote Anna. When I had given birth and breastfeeding had been established, I became obsessed with the thought of writing a normal book.

It’s very difficult to put together a whole, wrote Anna, to figure out what wholeness is and what it looks like. What is a whole Anna? What is the sum of her parts? These parts of me, separate yet linked, to connect them, to gather them in one place; that is my work.

After giving birth, Anna dressed and undressed the child for the first time. Carefully she coaxed the hospital onesie over the boy’s head. He began to cry and flail his arms and legs about.

‘Childbirth is hardest on the child,’ she had read in a book on parenting her aunt had given her. In another book, she had read that Marguerite Duras had said that birth was an assassination of the child. Gently she lifted his soft arm and pulled his clenched fist through the sleeve.

While she slept, Aksel had asked a nurse to show him how to change a nappy, and Anna laughed when he told her.

She dressed and undressed the child with a confidence that reassured them both.

She didn’t think it was innate, but indoctrinated since childhood.

Throughout the years, thousands of dolls had been dressed and undressed in Anna’s hands, and now, in the maternity ward, Anna felt as though all this doll play had existed solely to prepare her for this moment, for this child. She raised and bent the boy’s arm to pull it through the sleeve. She carefully lifted him towards her and pulled the leggings up around his belly while his feet rested on the changing pad. Nothing had prepared her for his eyes and for the horror.

Many years later, it occurred to Anna that the reason people didn’t tell mothers-to-be about the terror was that they themselves wished to forget it. When the child was older, Anna too had almost forgotten, and it was only in reading these documents she was reminded that it had existed, that it still existed in her, and even then, when faced with these pages, Anna felt a deep ambivalence, tempted to destroy them, delete all signs of this terror that lived deep in the heart of becoming a mother. There was no room for it in society. There was no room for it in Anna. The terror took up far too much space so there was hardly any room for love. To love was a mother’s foremost task, her most important work. How to love when there is terror? How to live with terror instead of a heart? It would have to be Anna’s secret, she would carry on like everyone else, with a smile and a heart, a mother’s heart, a mother’s offering.

She washed the child’s clothes with the utmost care.

She separated the little items into whites, darks and reds and washed them at 40 degrees. Cloth nappies and bedding at 60 degrees. Jumpers and wool and silk, delicates, thin summer knitwear at 30 degrees.

She hung the clothes on the drying rack on the balcony while he slept. She smoothed them out and folded them meticulously.

Before giving birth, she washed and ironed all the baby clothes she had collected, then folded and packed them in a box she stowed at the bottom of the closet, along with a grey plush penguin. Her favourite item was a bright-red onesie made of wool with a zipper in the front edged with white trimming. A Christmas onesie.

If clothes or nappies were still yellow from faeces after washing, she would lay them out on the kitchen windowsill for the sun to bleach the stains away.

The objects were a means of approach. She understood the child through the objects that belonged to the child’s world. She understood that the child was growing through the increasing size of his onesies.

When Aksel did the laundry, he couldn’t tell the difference between wool and cotton, to Anna’s endless amusement, so she showed him two jumpers, one of cotton and one of wool.

‘See, you can feel the difference,’ she said, rubbing the fabric between her fingers. But he couldn’t, no matter how hard he tried. He didn’t have the same affinity for textiles as Anna, although he too enjoyed nice clothes.

He didn’t have it in him, this eye for it, the ability to zero in on the weave, the length of the threads, the fine ravellings, the very fibres that made up various textiles. He hadn’t conversed with sales assistants in artificially-lit department stores about the correct way to wash chiffon. Most likely, the majority of his garments had been designed to be washed in a good-old 40-degree cycle without any fuss. Sadly, most men did not wear lace.

Anna, meanwhile, lived in the world of textiles. She had long dreams about moving through swathes of wet and dyed fabrics. And often she would dream about sorting through piles of clothing someone had left behind in the attic, or about packing endless heaps of clothes into bigger and bigger bags.

Anna realised her relationship not only to textiles but to all the objects of the home was different to Aksel’s. Objects settled deep inside her; she knew them.

The herbs on the windowsill, the various glasses and jars of flour and beans, the linens in the closet, several of which were monogrammed with her grandmother’s initials, and also the scent in between these folded sheets when you lifted out a clean duvet cover, the dough rising in its bowl, the wool jumpers on the highest shelf, the soap. Anna suspected this deep union with the objects of the house was the result of her upbringing. Had Anna been taught not only to be a housewife but to be one with the house itself, to be an object among objects? Had the work of the home given her a particular sense of the life of objects?

Anna had always preferred to read and write in secret, and she would tell people that books and writing offered a refuge, a secret life.

But was the real reason not that writing brought Anna closer to all the objects in the world? And that in this way she became less human, that in her writing she could seek to become an object? Here, happily objectified by writing, she felt more like Anna, more alive than otherwise. Was Anna not human?

It was not through housekeeping but through writing that she wished to approach all the objects of the world. Was writing in that case a form of housekeeping? A way of bringing things into order? When Adam named everything in the Garden of Eden, was he in fact doing the work of a housewife?

Anna wanted to live and did live close to the textiles, the minerals, the food, to the plants and the dust and the smells and to the elements and the small animals. And in Anna’s eyes, everything was knickknacks, everything was miniature, it all belonged to the world of objects and animals. The toys and the children’s clothes. The organs in their bodies. The child’s liver and heart.

When the boy was born, Anna was afraid he would be an ugly child. Or rather, she wasn’t afraid of him being ugly, but of not being able to tell whether or not he was beautiful. That visitors would walk over to his cot and say ‘What a beautiful child’, but were lying to Anna out of politeness.

Anna was afraid of being trapped in the lie without knowing it. Sequestered from everyone else in another reality, from which she could not escape. How could you truly see your child?

‘I’m afraid he’ll be ugly,’ she said to Aksel, who got angry and said: ‘Of course he won’t be.’

It tormented her to live inside the lie of the beautiful child. It tormented her to have to wonder whether the child was beautiful or ugly. It tormented her to have such thoughts about her own child. The child was her flesh and blood, literally. He had been formed inside her and expelled from her body a few days ago, uncorded, examined, washed, alive. He was her and he was not her. She could not see herself.

When Anna was pregnant, she and Aksel, who was Swedish, agreed to move to Stockholm for a while after the child was born. Everything had been planned before the birth, they believed they had the next twelve months all worked out. With the help of his mother, Aksel had found an apartment for them in Hammarbyhöjden – a charming suburb, Anna gathered, close to the woods and a lake, as well as to public transport. He had also managed to arrange it so that the play he was working on would premiere in Uppsala in December, while they were in Sweden. He was proud of having landed it, was keen to show he had connections in Sweden. They would wait to move until the child was five months old, that fit with the timing of their parental leave; there would be an overlap where they would be at home together once Aksel had finished a play in Malmö. The plan was that Anna would gradually start writing again, perhaps return to Denmark with a manuscript for a book when the child was one, or they could stay in Sweden, perhaps she could get a job, they knew someone who taught a group of young Scandinavian students, a literature class, where Anna had been offered the chance to run a week-long seminar later in the year. It was still a long way off. It was September. They packed up and sublet their apartment, held a small goodbye dinner, Anna pushed the pram out of the yellow shed in the courtyard and looked up at the windows of the apartment that had been the child’s first home. She felt a chill at the thought of what was to come. She was extremely tired and very, very awake.

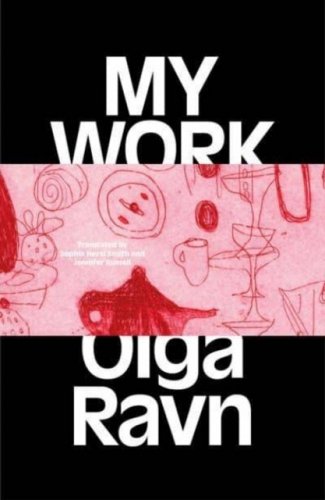

Image © Philippa Willitts