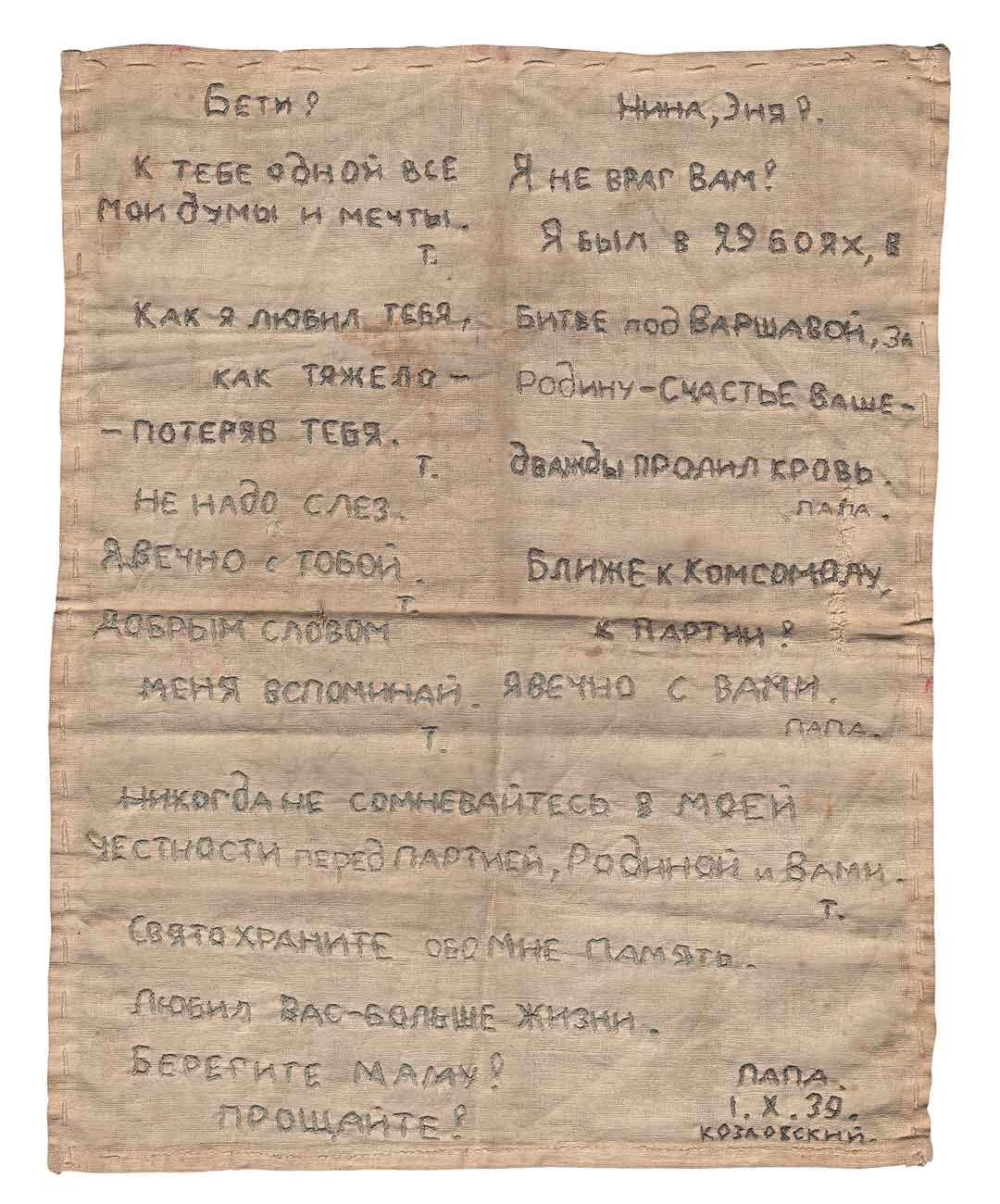

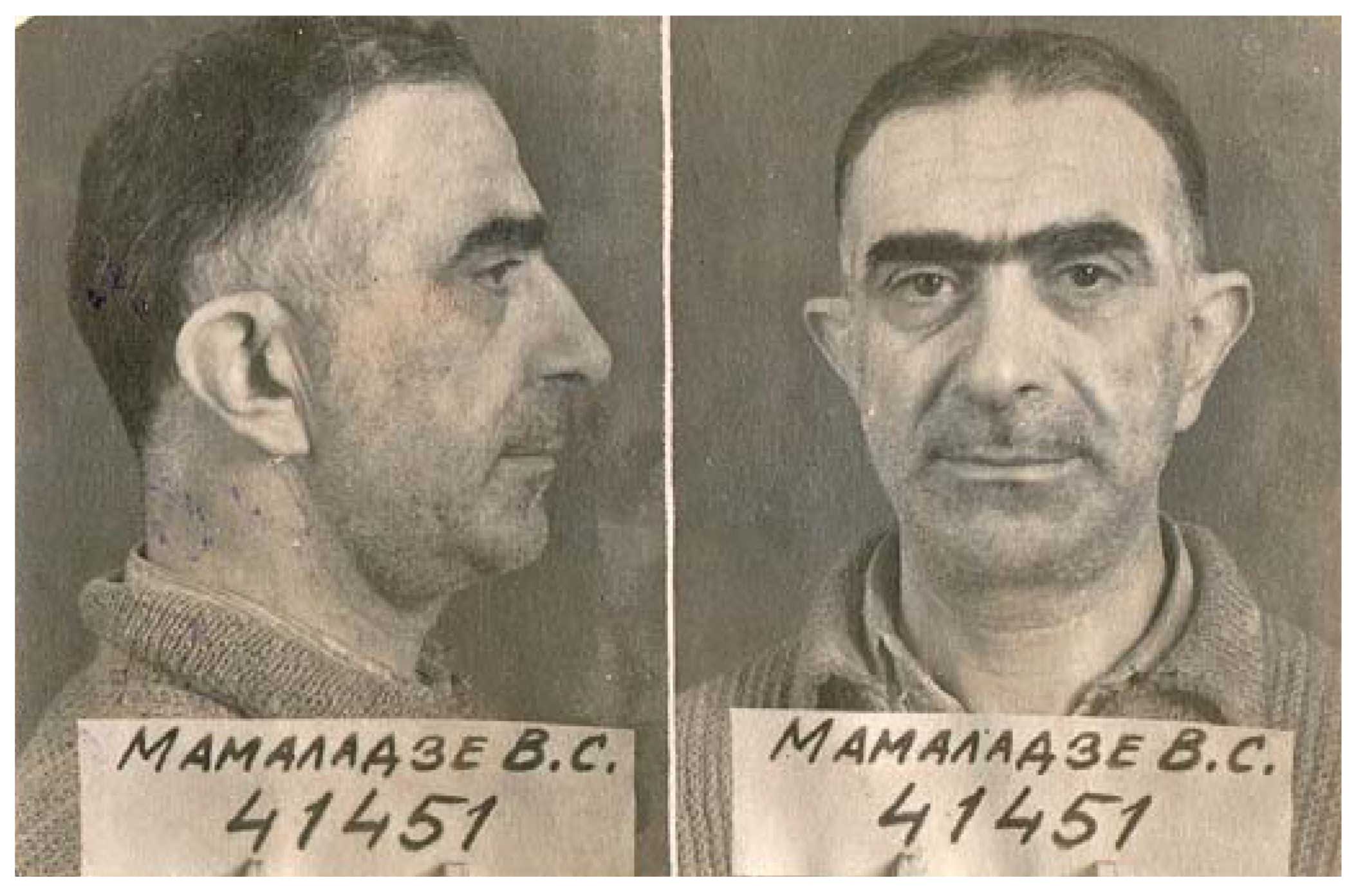

This book, pieced together from the archives of Memorial, an international history and human rights organisation, tells the stories of sixteen different families through letters sent home by fathers imprisoned in Stalin’s infamous Gulag system. My Father’s Letters seeks not only to shed light on the fates of families such as these, but also to illustrate the momentous role that written correspondence has played in the preservation of family memories of repression.

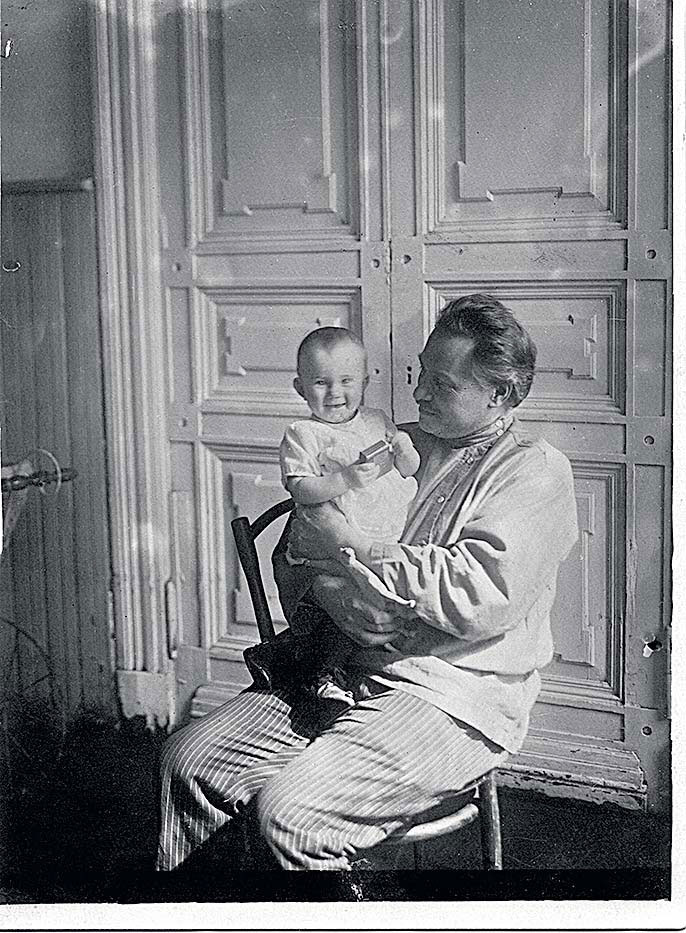

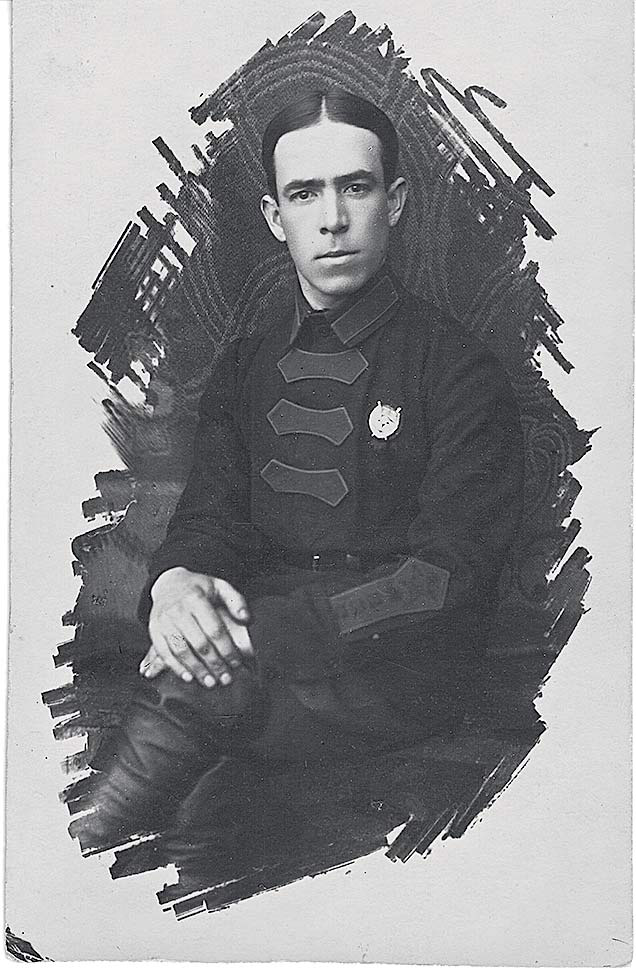

Messages from prisons and camps, notes passed from neighbouring cells or thrown from trains bearing prisoners bound for a distant Gulag, and letters from relatives or loved ones to those who had been torn from their families, all constitute a significant share of Memorial’s archives. This is far from coincidental. In fact, one of Memorial’s primary tasks when it was founded in 1989 was to begin establishing an archive as a place of memory, both individual and collective, that would enable the recollection of the lives and fates of those who lived through this period of repression. Very often, family memories from Soviet citizens who lived through the first half of the twentieth century are limited to a couple of letters, and perhaps one or two photographs or documents, hidden in a biscuit tin or tucked away in an old briefcase up in the attic. Occasionally it was possible to save a parent’s bookshelf or writing desk, but only in the event that the remaining relatives managed to avoid arrest or exile and succeeded in safeguarding the remnants of the family home. Memorial became a place where people could bring the fragments of family memories and piece them together with those of thousands of others, to form part of an elaborate jigsaw chronicling the past.

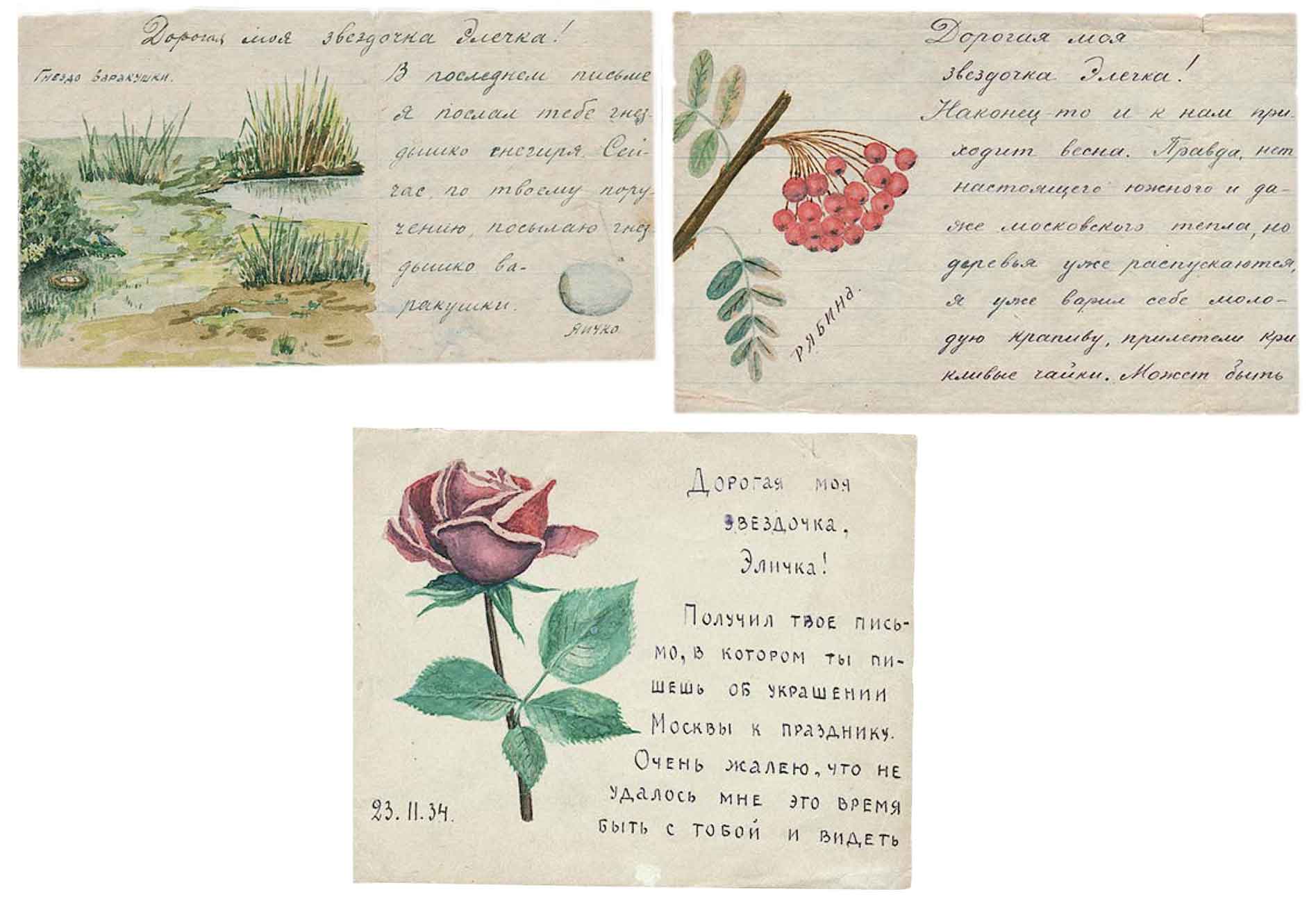

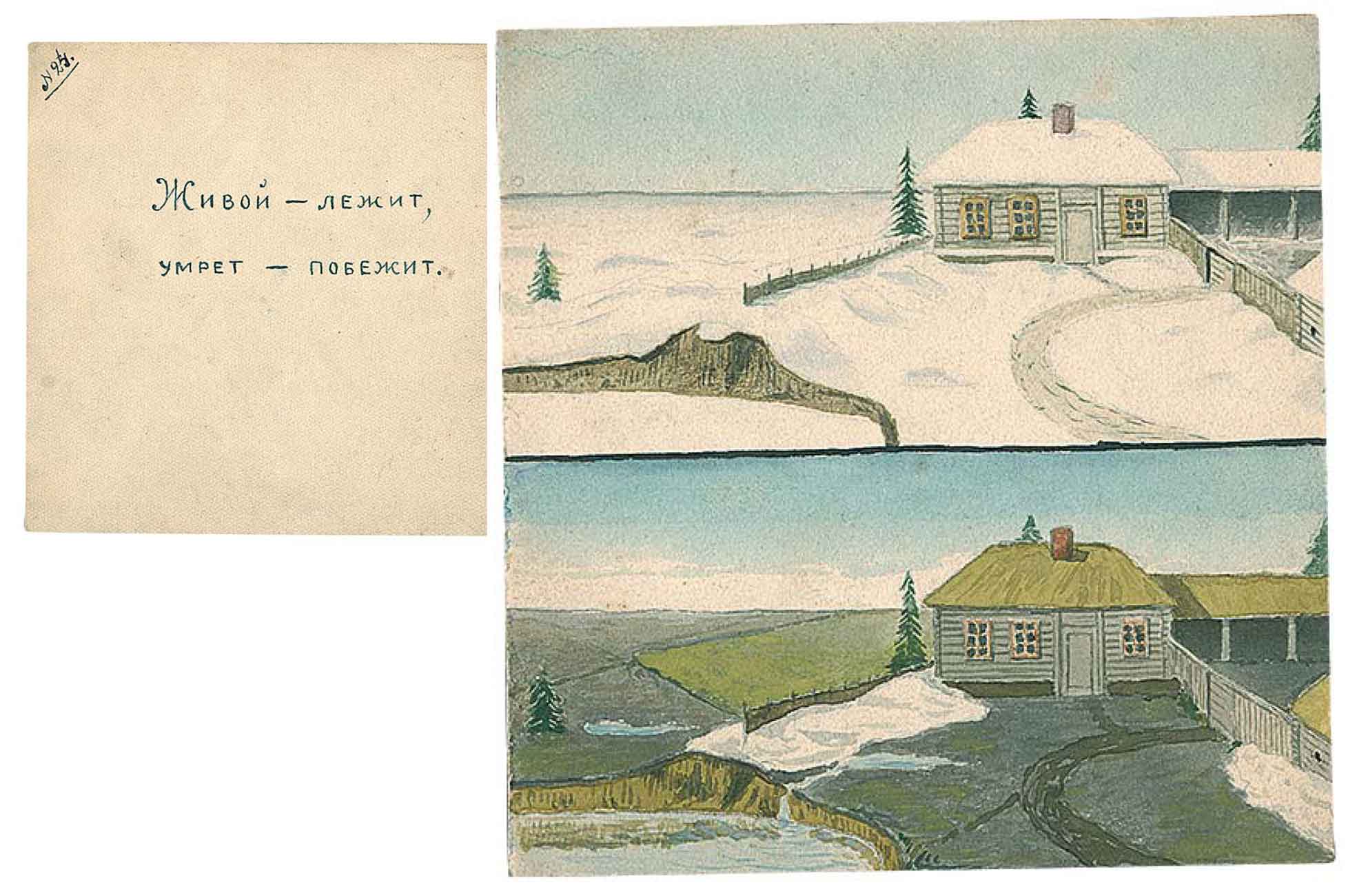

The letters donated to Memorial’s archives provide a wealth of information on the lives of the men and women who sent them and they provide detailed reports of life in both prisons and camps, and in freedom and exile. Precious opportunities to relay such information had to be seized, but there was often a degree of reticence in sharing it, which was not only due to an awareness of camp censorship (if the letter was to go via official channels), but also because the fathers often wished to avoid overly distressing the recipients of their letters. The task of sharing information was far from easy, but this makes the remarkably true-to-life letters written by men such as Yevgeny Yablokov all the more important and poignant. Yablokov describes daily life in the camps in such detail that his letters read almost like a Robinson Crusoe survival story. They are testimony to man’s capacity to make the most of life, and to endure.

Irina Scherbakova