The human rights organisation Memorial, established in 1987 by human rights activists in the former Soviet Union, is one of three recipients of the 2022 Nobel Peace Prize.

‘Memorial is based on the notion that confronting past crimes is essential in preventing new ones,’ said the Nobel Committee. For decades the organisation has compiled evidence of corruption and human rights violations in Russia, gathering information about the victims of the Stalinist era and documenting the location of contemporary political prisoners.

Over the last five years, Granta Books has collaborated with Memorial to publish three books that each draw on the organisation’s vital archival work.

Translated by Arch Tait

In the archives of the Memorial International Human Rights Centre in Moscow is an extraordinary diary, a rare first-person testimony of a commander of guards in a Soviet labour camp.

Ivan Chistyakov was sent to the Gulag in 1937, where he worked at the Baikal-Amur Corrective Labour Camp for over a year. Life at the Gulag was anathema to Chistyakov, a cultured Muscovite with a nostalgia for pre-revolutionary Russia, and an amateur painter and poet. He recorded its horrors with an unmatchable immediacy, documenting a world where petty rivalries put lives at risk, prisoners hacked off their fingers to bet in card games, railway sleepers were burned for firewood and Siberian winds froze the lather on the soap.

From his stumbling poetic musings on the bitter landscape to his matter-of-fact grumbles about his stove, from accounts of the conditions of the camp to reflections on the cruelty of loneliness, this diary is unique – a visceral and immediate description of a place and time whose repercussions still affect the shape of modern Russia.

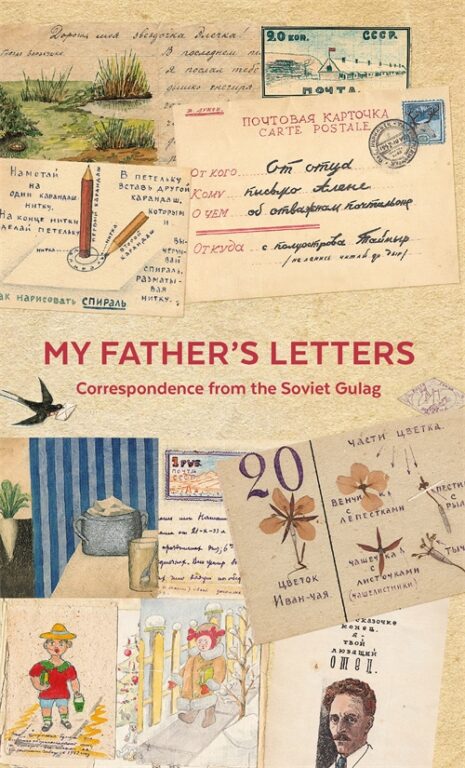

Translated by Georgia Thomson

Between the 1930s and 1950s, millions of people were sent to the Gulag in the Soviet Union. My Father’s Letters tells the stories of 16 men – mostly members of the intelligentsia, and loyal Soviet subjects – who were imprisoned in the Gulag camps, through the letters they sent back to their wives and children. Here are letters illustrated by fathers keen to educate their children in science and natural history; the tragic missives of a former military man convinced that the terrible mistake of his arrest will be rectified; the ‘letter’ stitched on a bedsheet with a fishbone and smuggled out of a maximum security camp. My Father’s Letters is an immediate source of life in prison during Stalin’s Great Terror. Almost none of the men writing these letters survived.

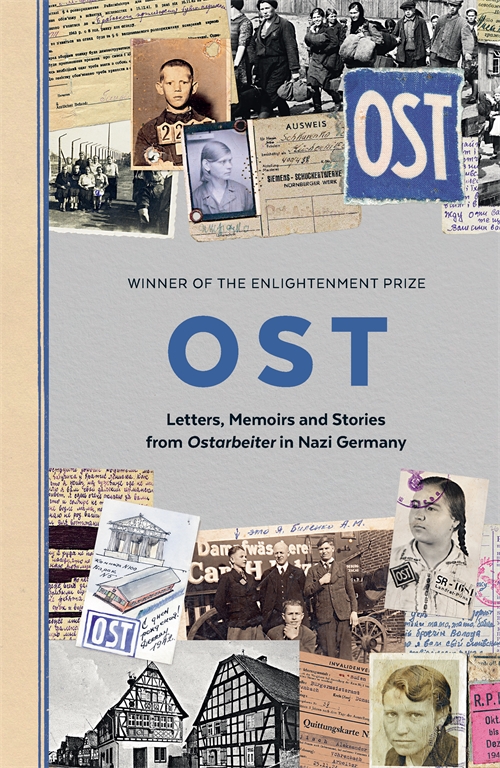

Translated by Georgia Thomson

An Ostarbeiter was an ‘Eastern Worker’, rounded up by Nazi Germany from the captured territories in Central and Eastern Europe. By the end of the war, it is estimated that approximately 3 million to 5.5. million Ostarbeiter were forced to work in guarded work camps, many of them younger than 16 years old – at which age they would be conscripted for military service. Ostarbeiter worked 12 hours a day on starvation on rations; as ethnic Slavs, they were treated with extraordinary brutality by Nazi guards who considered them ‘sub-human’ by the standards of the Aryan master race. They were distinguished by the label ‘OST’ sewn onto their uniforms.

OST is based on over two hundred personal accounts, hundreds of hours of interviews, and over 350,000 letters. This important publication will ensure that the voices of the brutalised and displaced Ostarbeiter will not be forgotten.