For five years I had been making a documentary about Vienna. Half the film chronicled the Viennese invention of the modern architecture of home. I explored dreams of homemaking dreamed by the city’s leading architects, artists and thinkers – Klimt, Adolf Loos, Freud, Wittgenstein, etc. – as they tried to make the expanding capital of the Habsburg Empire livable for ethnically diverse and mutually antagonistic immigrants. The other half was personal. It revolved around a painting by my father depicting the living room of his childhood home in Vienna, with his parents, Leo and Fanny Körner, safe inside. My father had escaped Austria in 1938, leaving his parents behind. He created the painting from memory in 1944 in Washington DC, while waiting to be shipped to Europe as an officer in the information branch of the US Army. It came to hang above my childhood bed in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where my father met my mother and settled in 1952. What fascinated me about the work was less its meticulous inventory of my grandparents’ vanished home than a strange coincidence that occurred in it. Through a window in the depicted living room, at the far end of a vertiginous street view my father managed almost photographically to recollect, there appeared, tiny but recognizable through their distinctive semicircular entablatures, the two windows of our own top-floor apartment in Vienna, where we spent our summers. Back in 1944, when my father reimagined them, our apartment’s windows belonged to a kind of pictorial shorthand for other people’s homes. One long block of anonymous apartment buildings, each facade featuring scores of nearly, but never quite identical windows, ours happen to occur in the painting almost at its perspectival vanishing point – what in German is called the Fluchtpunkt, which means, literally, the point of flight or escape. By 1968, when we began to lease our two-room flat on the Volkertplatz, at the end of the street leading back to my father’s old home, no one realized that he had perfectly but inadvertently captured our telltale windows in his painting. To me, who first noticed the detail, the imaginary bridge spanning the two homes seemed uncanny.

In the film, my father’s painting starts as just one expression of the dream of the Viennese interior. It illustrates how ordinary people turned their small rented flats (everyone rents in Vienna) into beautiful enclaves. But exploring the later history of the apartment – how my grandparents were evicted to make room for ‘Aryan’ tenants, and how their neighbor in the apartment right next door, a fervent Nazi who claimed to have personally founded the Hitler Movement in Austria, seized the whole apartment building from its Jewish owners – the story veers to nightmare. Overnight, after Hitler’s 12 March 1938 annexation of Austria, Vienna’s 200,000 Jews effectively lost their right to live in the city. In the film the story of the Körners and their apartment is told by an archivist from the Israelitische Kultusgemeinde Wien ( Vienna Israelite Community). The Kultusgemeinde is where, since 1849, births and deaths of Vienna’s Jews are recorded. After 1938, the institution was forced to organize the emigration and deportation of Jews. For Fanny and Leo the paper trail turned out to be chillingly complete. Not only their forced ‘deregistration’ to Minsk, but also the precise facts of their transport there by train were fully documented. Commanded to report to a ‘collection point’ in the Sperlgasse for ‘resettlement’ in the German-occupied East, they departed in the early hours of 9 June 1942 from Vienna’s Aspang railway station aboard a special train with the designation Da 206 (the ‘Da’ stood for David, as in Star of David). At Vawkavysk, formerly Wołkowysk, the track gauge changed and passengers were forced from third-class cars into cattle cars – police reports record deaths already here.

Even with his excellent Czech, Polish, Belarus and Russian, our archivist struggled to read aloud the stations listed on the twisting route from Vienna to Minsk, since some of the towns had disappeared, their names forgotten or changed. Caught on film, his halting reading of these names from the original train report helped conjure the distance traversed. Further documentation revealed that in Minsk the 1,006 passengers of Da 206 were herded into trucks and driven twelve kilometers southeast to a place called Maly Trostinets. There on the afternoon of 15 June, within a stand of young pine trees deep in the Blagovshchina Forest, they were shot, their bodies then thrown into long ditches and covered with quicklime. Later transports arrived at Maly Trostinets by train along tracks that had been previously abandoned, and gas vans replaced murder by shooting, but the protocol – execution immediately upon arrival in the early afternoon – and the place in the forest remained the same.

Maly Trostinets, camp entrance, c. 1944

My son had helped with sound in an early interview for the film, and he had heard talk of a reconnaissance trip to Minsk and Maly Trostinets. In the end we decided to confine the filming to Vienna, letting the archivist’s voice gesture toward the unimaginable. But our failure to follow through on our plans bothered Leo. Reading up on the twentieth-century history of Belarus where, after starvation and mass killings already under Stalin’s rule, the Nazi occupiers killed about a third of the total population, including some 250,000 Jews, and where, since 1994, people still live under Soviet-style dictator Alexander Lukashenko, Leo proposed a journey by train from Vienna via Warsaw and Vawkavysk to Minsk. There we would stay in the gigantic Hotel Belarus, with its panoramic views of the city and an enormous swimming pool decorated with social-realist mosaics of athletes, Red Army liberators and muscular Viking Rus’. To orient ourselves we would visit the Museum of Architectural Miniatures, where most of Belarus’s monuments and castles can be visually explored in tiny scale models. Using Yandex.Taxi, the app which Leo promised to obtain, we would be driven out to the Mound of Glory, a pair of soaring bayonet-shaped obelisks atop a huge hill formed of scorched soil from the country’s ‘heroic’ destroyed cities, much of the soil carried by hand by schoolchildren. Time permitting we would spend an afternoon at the Stalin Line Museum. There a segment of the fortifications that ran along the erstwhile western border of the Soviet Union (built to withstand a Polish invasion but useless against the Germans in 1941) has been carefully restored, and vintage mortars and Kalashnikov rifles can be fired for a modest fee. Maly Trostinets itself, online comments report, could be reached only with difficulty by bus, and taxi drivers could not be expected to have heard of the place. The sprawling Memorial Complex was also said to be confusing, with monuments and plaques containing inaccurate or contradictory information. But Leo downloaded a whole library of maps and made certain that Minsk was a safe place even for tourists who had lost their way. His proposal was hard to turn down, since I had a week free in March, and his half-siblings, Ben and Sigi, were eager to join us from England. I also secretly regretted my own peculiar inertia, which had paralyzed me as far back as I can remember.

The fate of my father’s parents had always been the great family mystery. The Nazis had murdered almost all his relatives: this was all we knew and all we thought could be known. Two younger cousins managed to escape via child transports to England and Palestine, and they learned nothing more than that all the ones unknown to us, the ones living in Vienna as well as the oil-mining relatives in Boryslav and Stryi, in Galicia, now western Ukraine, had vanished without a trace. In the absence of facts, rumors flourished. In 1941 my father’s brother Kurt had been deported with his wife Olga to Kielce, in occupied Poland, and a letter to my father from his parents in Vienna seemed to suggest that they contemplated joining Kurt. This would have meant that they, together with Kurt and Olga, would have probably died in Treblinka after the liquidation of the Kielce ghetto in August 1942. Other concentration camps were sometimes named. A college course on the anthropology of kinship required from each student a family tree. I listed eighteen of the disappeared relatives on my father’s side as having died in Auschwitz, followed by a question mark. On the other hand, I dimly remembered having once been shown a note with the words ‘abgemeldet nach Minsk’ written on it in my mother’s hand. Abgemeldet (deregistered) was correctly spelled, so I assumed that my mother, who barely spoke German, must have transcribed the word from somewhere, or had it spelled out to her, but her recollection of where she got this information was cloudy and her theory about it – that her parents-in-law might have fled eastward into Russia – caused me to ignore the clue.

The idea that Leo and Fanny somehow survived obsessed my mother. For years she read nothing but Holocaust literature and collected newspaper stories about lost relatives turning up out of nowhere. She disliked her own parents up in Escanaba, especially her father, whose Catholic piety concealed a violent temperament. And she had little in common with her sister’s family in Iowa – all incurious Lutherans who never once left the US. An aspiring concert violinist on a scholarship to a music conservatory in Pittsburgh, she met and married my father. Divorced, exotic and seventeen years her senior, my father was partly an escape from her own family. She identified with my father’s family and contemplated converting to Judaism even though my father’s parents had abandoned that faith. She felt closest to his mother, Fanny, who was supposed to have been independent, sensible and strong – as opposed to the supposedly passive, emotionally frozen Leo. She imagined Fanny still alive, alone and trapped in Siberia or China. My father did little to counter this fantasy. He would just shake his head in annoyance and mutter to my sister and me that this was ‘a bunch of shit’, while my mother held up her theory as yet more proof of his callousness. ‘Your father only thinks about himself.’

What exactly he knew remains to me a mystery, but that he knew that they were murdered was obvious. Reading through old letters, I found that already in 1946 my father had enquired at the Red Cross in Vienna and confirmed that his parents were dead. Furloughed from the army, he had also visited a close Christian family friend, an unmarried secretary at the national railway, who passed on to him some vital papers concerning his two surviving cousins. By the time I met her, Stefanie Lukas had become a deeply unpleasant old lady who forced us to call her ‘Aunt Steffi’ and whose apartment was crammed full of valuables originally belonging to my grandparents – we would have coffee and cakes with her seated around a table covered with a beautiful lace doily made by my grandmother’s hand. These things were probably given to her for temporary safekeeping, but she never admitted it, and at her death, out of spite, she left everything to her cleaning lady who (we think) kept the good things and threw everything else away. Having boarded for a time in my father’s family home, Aunt Steffi knew all about Leo and Fanny’s eviction, their reduced accommodation in two successive Jewish ‘collective apartments’ and their deportation to the East. She could have given a full account of their final days in Vienna, but she chose not to. Instead she spoke to us endlessly about her own plight during the war, and how, dressed in her office uniform, she stayed for days in one of the huge bunkers in the Augarten as the bombs destroyed the buildings all around.

In the army my father had served in the OSS, the Office of Strategic Service, the wartime predecessor of the CIA. He designed posters and brochures that publicized information on the enemy, including Nazi atrocities. After his discharge in April 1946, he re-enlisted in the US military government in Germany, so throughout the war and afterwards he had early access to facts about the Holocaust. The paintings he made in Berlin at the time, which established his international reputation, were explicit acknowledgments of, and monuments to, the murder of his parents. It was obvious to us as children that our yearly four-month stays in Vienna, made ostensibly so that my father could paint from life views of the city and its environs, were in fact a protracted form of mourning. Why else would we, each year, leave our happy life in Pittsburgh to travel to what seemed to us a ghost town in order to trail after my father while he looked for things to paint? And why else would we end up of all places there, on the Volkertplatz, in an apartment whose only selling point was its view? For me the painting of my grandparents in their living room came to symbolize this unquiet past. It must have been painted when my father had some hope that they were still alive. On the table between them, he shows the esoteric board game – an invention by his hobbyist father – still in play, with the blues and yellows almost tied. And he lets the string from his mother’s knitting rise up over the blown-glass arms of the chandelier and down to the little dancing ball of thread as if to connect himself and us viewers back to home, to the mother who, Penelope-like, weaves as she awaits the exiled hero’s return. And in fact, on forms filled out for his military service in 1944, when he painted that looping thread, he still listed his mother as his closest living relative. Via the painting’s glimpse of the Volkertplatz, then, the painting also managed continually to project this tiny but real glimmer of hope forward into the future, into our home that we therefore restlessly inhabited.

It wasn’t until 1997 that I discovered the facts. I was in Vienna writing the catalogue for a retrospective of my father’s work at the Belvedere. Knowing how reluctant the Viennese audience was about confronting its Nazi past, I felt queasy about my incurious vagueness concerning my grandparents’ deaths. ‘Auschwitz’ with a question mark felt woefully inadequate in such a context. Through a friend visiting from Oxford I chanced to meet Simon Wiesenthal, who told me to go to the ‘Bevölkerungsamt’ – he spoke the word slowly so I could write it down – but no institution by that name was to be found. Then, in the process of paying my German translator, I visited the offices of Illustrierte Neue Welt, a Jewish journal founded in 1897 by Theodor Herzl and still published in Vienna. There the editor-in-chief (my translator’s mother) told me what to do. You simply went to the Israelitische Kultusgemeinde and they would tell you everything there was to know. Later that day I found myself across the desk from the duty archivist in her windowless office adjacent to Vienna’s main synagogue. Before I could finish describing my mission, Frau Weiss reached for a big book of birth records and brusquely opened it to the right page: ‘Heinrich Sieghart Körner, born Vienna, August 28, 1915, died St Pölten July 4, 1991.’ It was less my father’s name, with its original, long-abandoned Wagnerian ‘Sieghart’, that took me by surprise than the precision concerning his recent death, because the archive felt so much like a time capsule, with old records preserved but no longer updated. While I mumbled something appreciative, Frau Weiss – on the basis of my father’s birth record – had swiftly located a slip of yellowed paper in a big cardboard box, which she laid neatly before me. There, written in ink in one script, was the name ‘Leo Körner’, and the words ‘mit Gattin nach Minsk’. A note had been added in another script in pencil ‘(deportiert)’. Remembering my mother’s mysterious note, I believed I stood again before the same impasse. But Frau Weiss, assuming a practiced bedside manner, explained that all of the more than 9,000 Viennese Jews officially deregistered to Minsk had in fact been forcibly deported – the word ‘deported’ on the yellowed slip had been added after 1945, probably by an archivist like Frau Weiss. And all these many thousands had only passed through Minsk, through back tracks in its freight train station, sent secretly on their way to a terrible place called Maly Trostinets. There they were all shot or gassed upon arrival. We know this, she explained, because of train records, war trials testimony and a single survivor’s report – only seventeen people were known to have survived transports from the German Reich ‘to Minsk’.

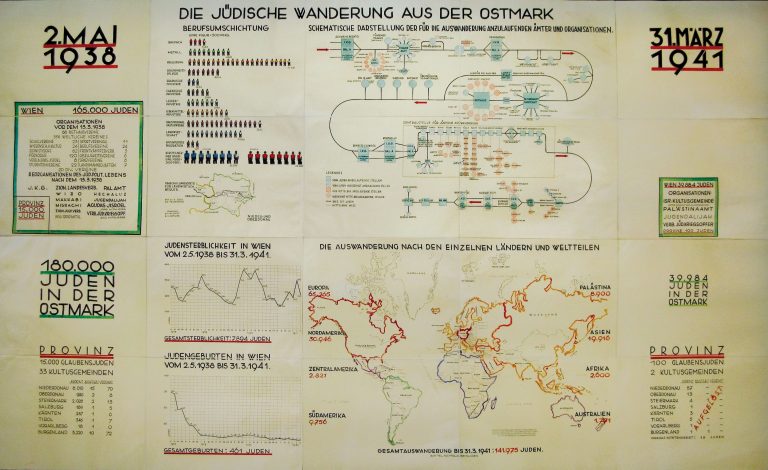

Frau Weiss then showed me an old handmade poster on her office wall diagramming the bureaucratic maze devised to make leaving Austria first difficult and expensive for the Jews and then impossible, as emigration turned into forced transport to death camps in the East. Created by someone employed in the Israelitische Kultusgemeinde Wien, the poster resembled Otto Neurath’s utopian Isotypes, but put to murderous use – its creator was probably killed in 1942.

Frau Weiss also gave me pamphlets to read. I learned that the use of Maly Trostinets as a killing site marked an important turning point in the Nazi genocide. Hitler intended his invasion of the Soviet Union to be a swift war of extinction. Not only was the Bolshevik enemy to be destroyed, entire populations were to be killed or starved to death to create Lebensraum for Germany. German and ‘Germanic’ colonizers would farm what would become the vast new breadbasket of his Thousand-Year Reich. By late 1941, Hitler steered these murderous plans more urgently toward the Jews. The masses of Jewish people in the conquered territories, together with the remaining Jews of Germany and Austria, would be transported by train to purpose-built killing factories. Unlike concentration camps, which killed some prisoners and worked others to death, these camps would exterminate new arrivals immediately, using poison gas, and their remains would be incinerated in huge crematoria. The few prisoners forced to do the gassing and burning would also be killed in efficient rotation, leaving no witnesses or evidence behind. Such operations would be undertaken in territories far to the east of the German Reich. Shrouded in the fog of war and soaked with the blood of Stalin’s atrocities, the lands around Minsk seemed optimum for this purpose. A railway hub, Minsk had long-distance tracks in all directions, as well as spur lines to obscure enclaves close by. One of these was the abandoned Soviet kolkhoz ‘Karl Marx’ beside the village of Maly Trostinets – the name means ‘Little Trostinets’ and has many alternative spellings: Trostenets, Trostinez, Trascianiec, Trostenec, Trastsianiets, Tras’tsanyets. With tracks leading into it, buildings sufficient to house guards and slave workers, and two secluded forests at its edge, this tiny settlement – emptied of its inhabitants and fenced as an off-limits Wehrdorf – became an improvised forerunner of the huge extermination camps under construction in occupied Poland, something between a killing site like Babi Yar and the industrial death facilities of Treblinka, Sobibor and Belzec.

The Jewish Emigration from Ostmark (Austria), hand-drawn wall poster on twenty sheets, 1941

The Jews of Vienna were the first in the German Reich to be deported for ‘resettlement’ in the East. This little-known distinction was the direct consequence of another forgotten Austrian first, the eviction of Jews from their homes in 1938. It was Vienna’s grassroots anti-Semitism that invented, suddenly and to the surprise of the Nazi authorities, the idea of rendering Jewish citizens homeless and at the mercy of the police. It was also mainly Viennese Jews who, between 6 May and 10 October 1942, were murdered in Maly Trostinets. Tens of thousands of Jews from elsewhere died there too, together with Soviet soldiers, Belarusian citizens, both Jewish and Christian, and partisans. The total estimated death count ranges from 80,000 to more than 300,000; the signage at the Memorial Complex claims 206,000, on the basis of an early Soviet report. After the Nazi defeat at Smolensk in October 1943, a massive secret exhumation action was launched to hide the killings from the approaching Red Army. Soviet prisoners were forced to reopen the ditches in the Blagovshchina Forest and carry the decomposed corpses – called figuren (figures) by the Nazi commander Arthur Harder – to a colossal bonfire, fueled by wood gathered forcibly from neighboring farmers. The unearthed remains were sifted for dental gold and burned in five-meter-high piles on a grill constructed of train rails.

Maly Trostinets’s existence was uncovered when the Red Army retook Minsk in July 1944 and found at its outskirts thirty-four huge smoldering pits filled with ashes, twisted tracks and human remains. After 1945 the area was forgotten, a fenced-off no man’s land. Parts became landfill – mushroom-shaped methane vents still stud the fields around the memorials, and in the 1990s, fragments of toppled Soviet-era monuments were dumped on the wasteland while new apartment blocks rose up all around. The history of Maly Trostinets was further obscured by the sheer number of killing sites in Belarus. During their three-year occupation, the Nazis destroyed, by some estimates, as many as 5,000 villages and 600 towns, killing most or all of the inhabitants, and operated at least seventy death camps. The Soviet authorities sealed the archives, since vast numbers of Belarusians had been murdered by Stalin’s secret police between 1938 and 1941, and in 1989 a Belarus commission indicated that at least 30,000 people perished in the woods of Kurapaty, just a few kilometers from Blagovshchina Forest. The place name Maly Trostinets itself disappeared from maps when the area became incorporated into greater Minsk. Until the 1990s, when the archives were opened up to historians, the enigma of my grandparents’ disappearance was a collective mystery shared by thousands of families with Viennese relatives.

We arrived in Minsk at an auspicious moment. In five days’ time, just after our departure, President Alexander Lukashenko together with Chancellor Sebastian Kurz of Austria and a host of dignitaries would inaugurate the first monument at Maly Trostinets to openly acknowledge the murder of Viennese Jews. Vladimir, our guide and a filmmaker who had just completed a documentary about the Minsk ghetto, had announced our visit to the Austrian ambassador to Belarus, as well as to Belarus state television, turning our visit into a minor public event. Vladimir’s daughter, an aspiring documentarian herself, filmed us together with the TV crew, as if to create a ‘making of’ film of the network coverage. In reality, she just hoped to put together a film for our family, while the television crew itself was just shooting B-roll for their coverage of the official ceremony. Rain was predicted for that day and interviews with survivors’ families would be harder to organize.

As a child I was troubled by having two persons in my head. One was an ‘I’ that lurked in silence deep inside me. The other was a voice, loud and vociferous, that narrated, usually mockingly, whatever it saw me doing. This ‘announcer’, as I called it, couldn’t be shut up, and if ever the inaudible ‘I’ managed to conjure a third person to speak on its behalf, the ‘announcer’ would only shout louder his rude commentary. Over time these struggles ebbed, perhaps because the ‘announcer’ finally became me. But Maly Trostinets somehow brought the two inner persons back to mind as I tried to edit out from my experience the various people documenting it, myself included. On the way to the Blagovshchina killing site, walking through five stylized train carriages intended to symbolize the last journey taken by victims before their death, Vladimir invited me to imagine my grandparents there. Speaking softly into my ear, he recalled what is known about those final moments, how the arrivals had to leave their labeled suitcases in a neat pile for later delivery, how they were fooled into thinking they had reached their promised new homes, and how, in groups small enough to control, they were forced to undress and kneel at the edge of the pit. I knew these details, all of them extracted from war trials testimony and a single witness report, and I would have wanted to walk the choreographed path by myself, or hand in hand with my children. But of course I could have done that as well, instead, and I was grateful to Vladimir for his effort, as I knew from long before that such imaginings were completely beyond me, and it now seemed indecent to my grandparents’ memory for me to picture them doing that here, in this real place where I walked.

On scores of trees in the forest, people had hung yellow laminated memorial plaques with the first names and death dates of murdered relatives. My children wandered under the tall pine trees looking for the names Fanny and Leo, to no avail. In the forest the TV crew turned their camera away; Vladimir stood quietly in the wings. I had the feeling of being, literally, too close to the trees to see the forest. The only past that came back to me was the one my father recollected most vividly: his parents, strolling in their beloved Vienna Woods.

The common German word for monument is denkmal, from denken (to think) and mal (to mark or to sign). Monuments are marks, sheer presences of one kind or another, that cause one to think, perhaps in a state of reproof – a German synonym for denkmal is mahnmal, from mahnen (to warn or to admonish). The word mal has a temporal charge and can also mean a point in time or an event, as in diesmal (this time) or es war einmal (once upon a time), and indeed most monuments are there to make us think about the past. The more historically conscious a culture, the more monuments it builds. In the nineteenth century, Germany was the veritable homeland of historical consciousness. There history came to be understood as the principal force and secret ‘cunning’ of human life. By a strange twist of irony, what the Germans did in the twentieth century precipitated the greatest dilemma in the history of monument-making: how to commemorate the Holocaust. Not only was there the problem that victors tend to erect monuments, and Germany was a defeated perpetrator; the cruelty and the scale of what had to be commemorated defied thought, while all traditional statements of warning, even the simple admonishment ‘to remember’, sound pedantic, as if made with the obscene presumption that such atrocities can ever be morally or historically understood.

In 2015, two tall bronze slabs formed of expressionistically rendered prisoners, fences and barbed wire, and representing prison camp gates set ajar, were erected at the newly landscaped Memorial Complex at Maly Trostinets. Called the Gates of Memory, the monument came with a text that spoke only of the ‘Minsk residents’ and ‘civilians deported from Europe’ who were murdered here. The familiar (and politically charged) omission of Jews as victims troubled many visitors to the site. One such visitor was Waltraud Barton. Born Protestant in Vienna, she had discovered that her paternal grandfather had divorced his first wife (a convert from Judaism) in 1938, and that, after serving as maid and nurse in the household of her now-remarried husband, she was sent to her death at Maly Trostinets. When Barton went to Maly Trostinets in 2010 to pay her respects to this forgotten family member, she was appalled to find no mention of Austrian Jewish victims and so she resolved to commemorate them, first unofficially through those yellow plaques, which she had organized, and then in the form of a permanent memorial, which eventually the Austrian government funded.

This was the monument about to be inaugurated when we made our visit, and our reactions to it were what Belarus television wanted to capture on film. Designed by the Viennese architect Daniel Sanwald and fabricated by the same Minsk sculptor who created the Gates of Memory, the new Massif of Names consists of ten closely packed columns cast from a clay model in dark gray fiber-reinforced concrete. Each pillar represents one of the train transports from Vienna, but the whole massif reads as a single fissured block, suggesting the compacted burial of bodies underneath. Its shape, dimensions, medium and avoidance of figuration recall Rachel Whiteread’s Holocaust memorial on the Judenplatz in Vienna, though Sanwald’s underlying idea is simpler than Whiteread’s. About halfway up all the pillars, in what looks from afar like erosion or damage, runs a concave frieze of first names. When we arrived at the monument, the film crew trained its cameras on the four of us circling the massif in search of the names of my grandparents. They turned out to be widely separated, but then, as we knew without saying, theirs were common Viennese names and could stand for any number of victims of that name. Vladimir encouraged us to put pebbles on the little platforms created by their names, according to Jewish graveyard custom. His daughter had two candles at hand, which my children lit in Leo and Fanny Körner’s honor.

But there was a nagging question. Since nearly all of the Viennese Jews killed at Maly Trostinets are known quite precisely by their full names and addresses, because the transport lists recorded these, why represent only first names? Why this insistence on anonymity when one powerful feature about this site is the fact that it contains such documented individuals? Austrians targeted their own meticulously registered and deregistered Jewish neighbors, and Austrians – railroad engineers, boilermen, train conductors, brakemen, stationmasters and policemen – participated knowingly in the killing, even vying with one another in their zeal, although one report survives of Viennese guards aboard the transport trains complaining of not having enough provisions for themselves, and of having to work on Sundays. An early transport was placed on a siding, with the Jews locked inside, while the Austrian train crew took Sunday off.

It turns out that it was the Belarus government that would not accept last names on the new monument. It was argued that such elaborate naming would dishonor the tens of thousands of Christian Belarusians murdered at Maly Trostinets whose names have disappeared. An old saying comes to mind: some people will never forgive the Jews for Auschwitz. Or as Thomas Hobbes put it, harm so grievous that it cannot be expiated ‘inclines the doer to hate the sufferer’. What made the Nazis so punctilious as murderers was that their final solution demanded every Jew be eradicated, as one stamps out every last virus of a deadly disease. Yet even though it was this distinctive murderous hatred that preserved for posterity the names of exterminated Jews, such distinction has bred a paradoxical second-order enmity. In the minds of some in Belarus, both the Nazi perpetrators and their special enemy belong to the long list of intruders. From this perspective, the first-names-only compromise is perhaps an effort to ‘decolonize’ the nation’s history. Rendering the Jewish dead anonymous equalizes historical representation that – so the thinking goes – has been monopolized by Jews.

I had been back in the States for about a week when I received from Vladimir a link to the official news report on the dedication ceremony. Broadcast on the All National Television, it began with an anchorman explaining that while Austria refused to remember a certain ‘page of its history’, President Lukashenko bravely called on all nations to create a monument ‘to the Austrian citizens of Jewish origin’ who died in Maly Trostinets. And suddenly there we were on film, searching the Massif of Names for Fanny and Leo. The camera had captured us artfully. Peeking around the monument’s edge, or finding us through its fissures, it made our movements look candid and private: a hand placing a pebble between the L and E of ‘Leo’, Leo my son lighting a candle for his namesake, the four of us huddled in silence in the cold March wind. And then, intercut with these shots, there was me speaking into the microphone about family history. That interview had made Leo uneasy. He worried about how things caught on other people’s cameras can come back to haunt you, although when his friends started forwarding the link he didn’t seem worried.

On the deeper question of whether it would have been better to have visited Minsk on our own, he was of two minds. The television crew had been distracting, and Vladimir had turned my attention away from the family and hijacked what Leo had intended as an intimate adventure. But he and his half-brother Ben had managed to sneak off to the GUM department store, torpedoing Vladimir’s ‘special bus tour’ of Minsk, and we avoided a curatorial tour of a School of Paris exhibition and instead walked the length of the city by ourselves to one of Leo’s planned destinations: a graveyard of Soviet-era statues, with huge heads of Stalin in plaster, stone and bronze balanced on cheap storage racks. But these outings felt like stolen moments. Sigi had arrived from the airport in the middle of a dinner at a gallery restaurant with no explanation of why we were there, and because our time was so densely scheduled, it wasn’t until the third day of our visit that she fully understood who Vladimir was and why he was in control. But she, Ben and Leo agreed that, on balance, our visit had been much richer thanks to our Belarus guides.

For me privacy had never really been an option. I contacted Waltraud Barton ostensibly to put us in safe hands which she did, through Vladimir, but I did so also to manage my encounter with Maly Trostinets through the buffer of outsiders. The trip felt to me like the coda to a film and not like the end of a journey, which is why it came as no surprise to find cameras on our arrival. My own film had been designed to avoid closure, since closure was impossible to achieve. Everything headed in the direction of my father’s childhood home, the place pictured in his painting, yet that home, indeed the whole apartment building, had been destroyed by a firebomb – in 1946 my father took a snapshot of its ruins and labeled the photo ‘My House’. Everyone working on the film agreed that the building that rose up from the rubble should not be shown, just as we, when we lived in that neighborhood, never looked up to those modern third-story windows that seemed like cruel impostors. Unable to bring closure, the film – or was it me, under the film’s control? – tried nightmarishly to repeat. It took its loving shots of ‘beautiful Vienna’ directly from paintings by my father, and it staged the interviews with archivists and historians as curious vignettes, like the ones my father painted in the city, with me and my sister posing as models.

I hated to pose for my father. Interrupting our free movement through the city, forcing me to stand still in strange positions for hours at a time, posing exposed me to my condition as an actor in someone else’s plot. And it confirmed the sense I had of myself as being always already narrated by that infernal ‘announcer’ to a silent audience of one. If I made peace with that inner demon it was only by putting myself in his position and telling the story of his story. The terms of that truce came back to me in Maly Trostinets. Approaching the pine forest with Vladimir’s voice in my ear, I found no one at home inside me to feel what I ought to have felt. Perhaps my children, who walked before me into the woods, were able to put the past to rest, but I cannot and will not speak for them.

Feature Artwork © Henry Koerner, My Parents I, 1944, courtesy of the artist’s estate