It is the first introductory BBQ of the fall workshop season, a time of new beginnings. The younger bard Anton Beans, emerging conceptual lyricist, the, who is he kidding, heir apparent to the poem-based sector of the American humanities multiverse, hovering beside the condiment table, is finally about to get across to Marta Hillary, award-winning poet and faculty member, the central conceit of his second, as-yet-unpromised manuscript, The Noise of Noise. Beans, who has been in the program for a year, arrived already under contract. His first collection, Distillation Metrics, will be published in May by a small but extraordinarily reputable press. Beans is all but guaranteed to secure academic tenure within the next five years, and he knows it. The only reason Beans temporarily abandoned San Francisco for the Midwest was to study under Marta, who is not just renowned but quite possibly the greatest poet of her generation. If she were not at the Seminars, he’s not sure what the point of his malingering here among so many reactionaries would be, although perhaps the degree itself is worth something.

Beans is twenty-eight years young. He has a PhD in linguistics and, before he left the Bay Area, was toiling very lucratively in consultation with certain IT interests, though he says nothing of this to his Seminars cohort. Beans is not a great fan of his fellow poetry students, in particular, nor is he a great fan of the arts, in general. As a toddler, he was pushed into show business. Beans appeared in a string of camera commercials before the onset of a stubborn form of childhood irritable bowel syndrome made his, albeit glowing and cherubic, face, due to its relative proximity to said bowels, unemployable.

From this early career loss, Beans learned the importance of a plan B. In his last year of grad school at Stanford, Anton Beans used some of his consulting fees (he, for the most part, was able to steer clear of options) to invest in real estate back in the city, buying a building on 24th and Mission. He knows exactly what he is sitting on, where it’s going in the next couple of decades.

Anton Beans is in some ways fairly unconcerned about his future. His ambitious mother, meanwhile, is pondering a second marriage to a cunning contractor.

What keeps Beans up at night is his own historical significance. He is not an academic, though he was happy enough to follow through with his degree. He isn’t really even a writer.

What it means not to ‘really’ be a writer: It’s not that Beans can’t write, because he definitely can, but that he does not exactly see the point, if you see his point, which it is unlikely that you do. If you understand anything at all about mankind these days then you know that the entire race has a rapidly approaching expiration date stamped on its forehead. All this business about symbolism and getting something or other eternal across to the sensitive souls who choose to buy your puny book is just so much outdated twaddle as far as he’s concerned. It’s a pipe dream of pre-network Romanticism.

All the same, Beans can’t quite rule out the importance of reading. And the fact that he can’t convince himself that the work of reading has no power and no allure and no gravitas suggests to him that there’s something he, Anton Beans, can and should do with the rest of his time on earth as far as literature is concerned.

Poems are good for Beans’s purposes because they’re short, because he can engineer a poem exhaustively, can attempt to determine its semantic capacity in a complete sense. His favorite writers are Gertrude Stein and Ezra Pound, individuals who, interestingly, did not seem to particularly care for each other.

Beans likes to dress as his own personal approximation of an anti-retinal, postwar American artist, basking in the soft power that comes of eschewing figurative content and, later, objects altogether. He would never bother living in inflationstruck New York City at this point, but he thinks Sol LeWitt’s appearance in the Cold War gallery system was pretty neat. He enjoys the utter primacy accorded the ‘concept’ by this exalted man. Beans stands with LeWitt, against rhetoric, against expression. Long live ‘the square and the cube as . . . syntax’! Long live logical sequence. Long live the beauty of evacuated form.

For the BBQ, Beans is wearing a pair of studiously, delicately paint-soiled white jeans, a white T-shirt, and white canvas sneakers from which he has painstakingly removed the logos using an X-ACTO knife. He began shaving his head bald several years ago and compensates for this elective scarcity by encouraging a pleasingly thick, wiry black beard of anarchic proportions to obscure his neck.

Beans is pretty sure that Marta does not know what to make of him, but that her refined and at least partially unconscious powers of pattern recognition have convinced her of his intelligence. He, for his part, would like: First, to secure a letter of recommendation from her, and, then, with this out of the way, to attempt to understand what makes her tick. If he were not currently practicing celibacy as a form of mental and spiritual self-discipline, it is likely that the two of them would be making love on a daily basis.

Marta is drinking white wine from a small green glass she must have brought for herself from home. Beans hovers at her side. Marta smells – he thinks, uncharacteristically employing simile – like an ocean breeze traveling along the tip of a rosebud. In fact, she is sex on a stick. Her face is small with a long, straight nose. Her jewelry makes elegant sounds.

‘So my procedure,’ Beans begins to explain, but here something very, very unpleasant occurs.

An enormous male-model type in a hot-pink hat inscribed with an obscene slogan appears at the condiment station. Beans’s fragile web is disturbed as Marta’s interest shifts. The bro has a pair of plump dogs over which he deploys nauseating quantities of ketchup, nodding approvingly to himself. A couple yards off, a weird, undersized person who looks a lot like a fraternity torture victim due to fading permanent marker drawings on his face, and who must be the wingman of the philistine, is miserably peeling the label from his beer bottle.

Marta turns away from Beans.

It is like this scumbag thinks Marta is another student, albeit one aging gracefully into her mid-forties via a budget that permits investment in Prada and the occasional foray into Comme des Garçons. And the truly frightening thing is that Marta seems to like it! She smiles that slow, dreamy smile of hers and offers the goon her hand. She greets him as if she remembers him from somewhere, which, if Anton Beans permits his worst fears momentary realization, must be his application to the program.

‘Troy Loudermilk,’ Marta says. ‘Welcome.’

The piece of shit is saying, ‘Welcome to you, too.’

‘Yes,’ Marta tells him. She makes no effort to introduce herself, rather examining the face of Troy Loudermilk. ‘You look so different?’

‘That’s funny,’ this most complacent of oafs replies. He is fussing with a pickle jar.

‘I meant, from how I’d imagined you,’ Marta finishes. ‘I never look at the photographs. It’s barbaric the university even makes us ask our students for them. The unaccountable needs of bureaucrats!’ Some stronger sentiment seems to flit across her face but is quickly dissolved under another indolent smile. ‘Lovely to see you.’

The kid with the cross on his forehead is staring at the ground so hard he may burn a hole into it. Beans likes him, if this is possible, even less than he likes Troy Loudermilk. Why someone like Loudermilk would put up with a specimen like that is a curious case. Probably has something to do with needing to seem plausibly human while you walk around looking like a boxer-briefs commercial.

Troy Loudermilk is saluting Marta. ‘Bye!’ he says, grinning moronically. He bears his submerged wieners away.

Marta watches Loudermilk go. ‘That is a very great poet, or so I believe.’ Marta eyes Beans. ‘We’ll have to see if he can live up to his potential.’

Beans forces himself to smile, he hopes enigmatically. ‘Anyway, about the manuscript,’ Beans recommences, ‘what you were saying was so –’ But he stops.

Marta has glided off. Beans is incensed to see her standing now in the company of Troy Loudermilk, Loudermilk’s presumably foot-long schlong, and Loudermilk’s bizarre minion, the last of the trio having already succeeded in smearing the entire lower half of his face in Heinz.

Beans watches Marta nod, watches her rest her shapely hand on Loudermilk’s shoulder and leave it there. More than anything else, Anton Beans hates the lucky. Not only do they absorb all the top prizes in life’s insipid games, but they have the habit of doing very little work in the process. Anton Beans abhors the lucky. They are the cherry on the top of humanity’s miscreation.

Beans turns to the cooler, roots furiously for a seltzer.

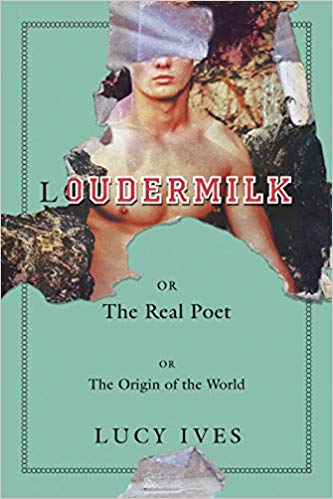

Photograph © green kozi