Last year I lost my cat Gattino. He was very young, at seven months barely an adolescent. He is probably dead but I don’t know for certain. For two weeks after he disappeared people claimed to have seen him; I trusted two of the claims because Gattino was blind in one eye, and both people told me that when they’d caught him in their headlights, only one eye shone back. One guy, who said he saw my cat trying to scavenge from a garbage can, said that he’d ‘looked really thin, like the runt of the litter’. The pathetic words struck my heart. But I heard something besides the words, something in the coarse, vibrant tone of the man’s voice that immediately made another emotional picture of the cat: back arched, face afraid but excited, brimming and ready before he jumped and ran, tail defiant, tensile and crooked. Afraid but ready; startled by a large male, that’s how he would’ve been. Even if he was weak with hunger. He had guts, this cat.

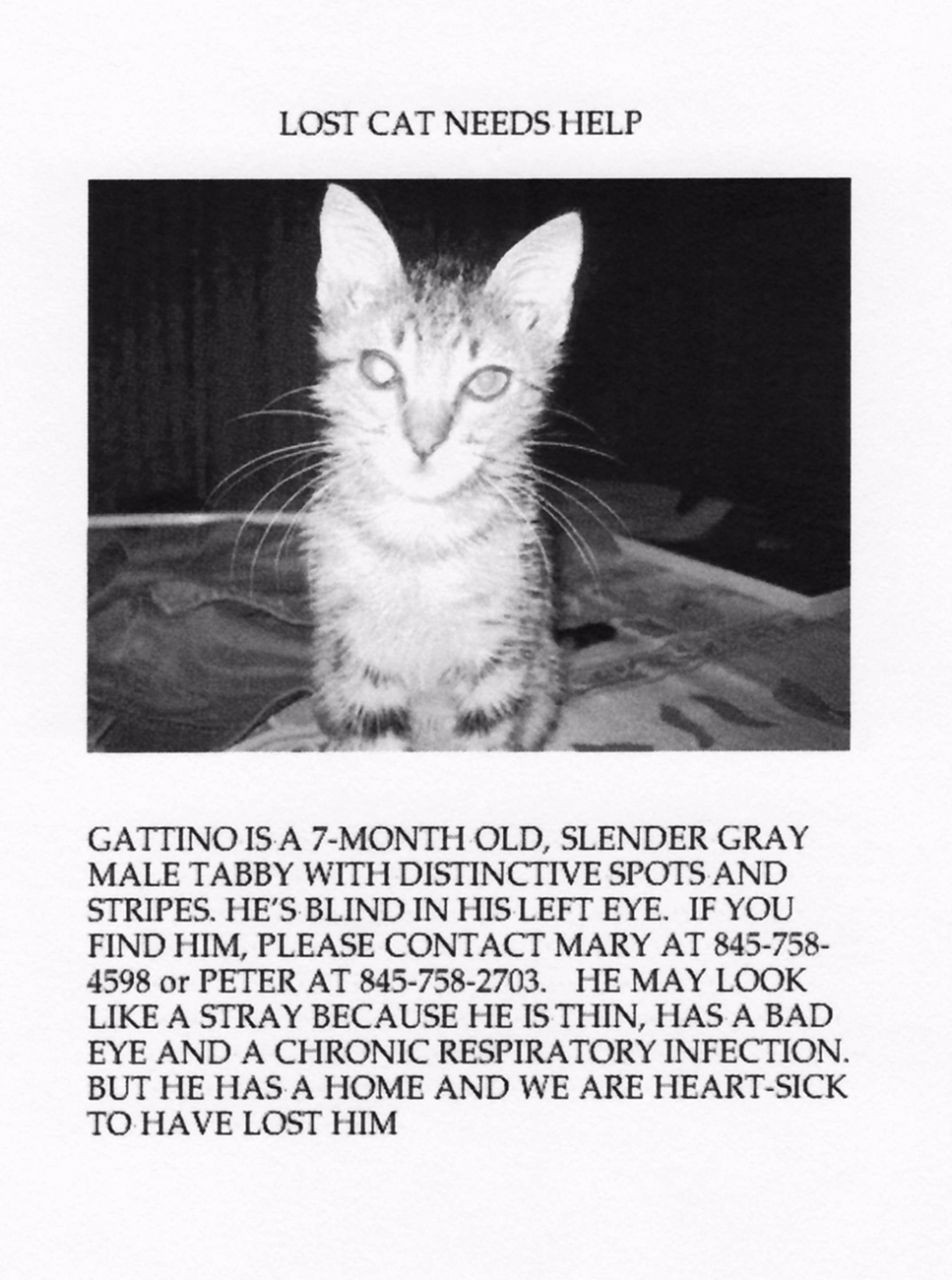

Gattino disappeared two and a half months after we moved. Our new house is on the outskirts of a college campus near a wildlife preserve. There are wooded areas in all directions, and many homes with decrepit outbuildings sit heavily, darkly low behind trees, in thick foliage. I spent hours at a time wandering around calling Gattino. I put food out. I put a trap out. I put hundreds of flyers up, I walked around knocking on doors, asking people if I could look in their shed or under their porch. I contacted all the vets in the area. Every few days, someone would call and say they had seen a cat in a parking lot or behind their dorm. I would go and sometimes glimpse a grizzled adult melting away into the woods, or behind a building or under a parked car.

After two weeks there were no more sightings. I caught three feral cats in my trap and let them go. It began to snow. Still searching, I would sometimes see little cat tracks in the snow; near dumpsters full of garbage, I also saw prints made by bobcats or coyotes. When the temperature went below freezing, there was icy rain. I kept looking. A year later I still had not stopped.

Six months after Gattino disappeared my husband and I were sitting in a restaurant having dinner with some people he had recently met, including an intellectual writer we both admired. The writer had considered buying the house we were living in and he wanted to know how we liked it. I said it was nice but it had been partly spoiled for me by the loss of our cat. I told him the story and he said, ‘Oh, that was your trauma, was it?’

I said yes. Yes, it was a trauma.

You could say he was unkind. You could say I was silly. You could say he was priggish. You could say I was weak.

A few weeks earlier, I had an email exchange with my sister Martha on the subject of trauma, or rather tragedy. Our other sister, Jane, had just decided not to euthanize her dying cat because she thought her little girls could not bear it; she didn’t think she could bear it. Jane lives in chronic pain so great that sometimes she cannot move normally. She is under great financial stress and is often responsible for the care of her mother-in-law as well as the orphaned children of her sister-in-law who died of cancer. But it was her cat’s approaching death that made her cry so that her children were frightened. ‘This is awful,’ said Martha. ‘It is not helping that cat to keep him alive, it’s just prolonging his suffering. It’s selfish.’

Martha is in a lot of pain too, most of it related to diabetes and fibromyalgia. Her feet hurt so badly she can’t walk longer than five minutes. She just lost her job and is applying for disability which, because it’s become almost impossible to get, she may not get, and which, if she does get, will not be enough to live on, and we will have to help her. We already have to help her because her COBRA payments are so high that her unemployment isn’t enough to cover them. This is painful for her too; she doesn’t want to be the one everybody has to help. And so she tries to help us. She has had cats for years, and so knows a lot about them; she wanted to help Jane by giving her advice, and she sent me several emails wondering about the best way to do it. Finally she forwarded me the message she had sent to Jane, in which she urged her to put the cat down. When she didn’t hear from Jane, she emailed me some more, agonizing over whether or not Jane was angry at her, and wondering what decision Jane would make regarding the cat. She said, ‘I’m afraid this is going to turn into an avoidable tragedy.’

Impatient by then, I told her that she should trust Jane to make the right decision. I said, this is sad, not tragic. Tragedy is thousands of people dying slowly of war and disease, injury and malnutrition. It’s Hurricane Katrina, it’s the war in Iraq, it’s the earthquake in China. It’s not one creature dying of old age.

After I sent the email, I looked up the word ‘tragic’. According to Webster’s College Dictionary, I was wrong; their second definition of the word is ‘extremely mournful, melancholy or pathetic’. I emailed Martha and admitted I’d been wrong, at least technically. I added that I still thought she was being hysterical. She didn’t answer me. Maybe she was right not to.

I found Gattino in Italy. I was in Tuscany at a place called Santa Maddalena run by a woman named Beatrice von Rezzori who, in honor of her deceased husband, a writer, has made her estate into a small retreat for writers. When Beatrice learned that I love cats, she told me that down the road from her two old women were feeding a yard full of semi-wild cats, including a litter of kittens who were very sick and going blind. Maybe, she said, I could help them out. No, I said, I wasn’t in Italy to do that, and anyway, having done it before, I know it isn’t an easy thing to trap and tame a feral kitten.

The next week one of her assistants, who was driving me into the village, asked if I wanted to see some kittens. Sure, I said, not making the connection. We stopped by an old farmhouse. A gnarled woman sitting in a wheelchair covered with towels and a thin blanket greeted the assistant without looking at me. Scrawny cats with long legs and narrow ferret hips stalked or lay about in the buggy, overgrown yard. Two kittens, their eyes gummed up with yellow fluid and flies swarming around their asses, were obviously sick but still lively – when I bent to touch them, they ran away. But a third kitten, smaller and bonier than the other two, tottered up to me mewing weakly, his eyes almost glued shut. He was a tabby, soft gray with strong black stripes. He had a long jaw and a big nose shaped like an eraser you’d stick on the end of a pencil. His big-nosed head was goblin-ish on his emaciated pot-bellied body, his long legs almost grotesque. His asshole seemed disproportionately big on his starved rear. Dazedly, he let me stroke his bony back – tentatively, he lifted his pitiful tail. I asked the assistant if she would help me take the kittens to a veterinarian and she agreed; this had no doubt been the idea all along.

The healthier kittens scampered away as we approached and hid in a collapsing barn; we were only able to collect the tabby. When we put him in the carrier, he forced open his eyes with a mighty effort, took a good look at us, hissed, tried to arch his back and fell over. But he let the vets handle him. When they tipped him forward and lifted his tail to check his sex, he had a delicate, nearly human look of puzzled dignity in his one half-good eye, while his blunt muzzle expressed stoic animality. It was a comical and touching face.

They kept him for three days. When I came to pick him up, they told me he would need weeks of care, involving eye ointment, ear drops and nose drops. The Baroness suggested I bring him home to America. No, I said, not possible. My husband was coming to meet me in a month and we were going to travel for two weeks; we couldn’t take him with us. I would care for him and by the time I left, he should be well enough to go back to the yard with a fighting chance.

So I called him ‘Chance’. I liked Chance as I like all kittens; he liked me as a food dispenser. He looked at me neutrally, as if I were one more creature in the world, albeit a useful one. I had to worm him, de-flea him and wash encrusted shit off his tail. He squirmed when I put the medicine in his eyes and ears, but he never tried to scratch me – I think because he wasn’t absolutely certain of how I might react if he did. He tolerated my petting him, but seemed to find it a novel sensation rather than a pleasure.

Then one day he looked at me differently. I don’t know exactly when it happened – I may not have noticed the first time. But he began to raise his head when I came into the room, to look at me intently. I can’t say for certain what the look meant; I don’t know how animals think or feel. But it seemed that he was looking at me with love. He followed me around my apartment. He sat in my lap when I worked at my desk. He came into my bed and slept with me; he lulled himself to sleep by gnawing softly on my fingers. When I petted him, his body would rise into my hand. If my face were close to him, he would reach out with his paw and stroke my cheek.

Sometimes, I would walk on the dusty roads surrounding Santa Maddalena and think about my father, talking to him in my mind. My father had landed in Italy during the Second World War; he was part of the Anzio invasion. After the war he returned as a visitor with my mother, to Naples and to Rome. There is a picture of him standing against an ancient wall wearing a suit and a beret; he looks elegant, formidable and at the same time tentative, nearly shy. On my walks I carried a large, beautiful marble that had belonged to my father; sometimes I took it out of my pocket and held it up in the sun as if it might function as a conduit for his soul. My father died a slow painful death of cancer, refusing treatment of any kind for as long as he was able to make himself understood, gasping, ‘No doctors, no doctors.’ My mother had left him years before; my sisters and I tended to him, but inadequately, and too late – he had been sick for months, unable to eat for at least weeks before we became aware of his condition. During those weeks I thought of calling him; if I had I would’ve known immediately that he was dying. But I didn’t call. He was difficult, and none of us called him often.

My husband did not like the name Chance and I wasn’t sure I did either; he suggested McFate, and so I tried it out. McFate grew stronger, grew a certain one-eyed rakishness, an engaged forward quality to his ears and the attitude of his neck that was gallant in his fragile body. He put on weight, and his long legs and tail became soigné, not grotesque. He had strong necklace markings on his throat; when he rolled on his back for me to pet him, his belly was beige and spotted like an ocelot. In a confident mood, he was like a little gangster in a zoot suit. Pensive, he was still delicate; his heart seemed closer to the surface than normal, and when I held him against me, it beat very fast and light. McFate was too big and heartless a name for such a small fleet-hearted creature. ‘Mio Gattino,’ I whispered, in a language I don’t speak to a creature who didn’t understand words. ‘Mio dolce piccolo gatto.’

One night when he was lying on his back in my lap, purring, I saw something flash across the floor; it was a small, sky-blue marble rolling out from under the dresser and across the floor. It stopped in the middle of the floor. It was beautiful, bright, and something not visible to me had set it in motion. It seemed a magical and forgiving omen, like the presence of this loving little cat. I put it on the windowsill next to my father’s marble.

I spoke to my husband about taking Gattino home with us. I said I had fallen in love with the cat, and that I was afraid that by exposing him to human love I had awakened in him a need that was unnatural, that if I left him he would suffer from the lack of human attention that he never would have known had I not appeared in his yard. My husband said, ‘Oh no, Mary . . .’ but in a bemused tone.

I would understand if he’d said it in a harsher tone. Many people would consider my feelings neurotic, a projection onto an animal of my own need. Many people would consider it almost offensive for me to lavish such love on an animal when I have by some standards failed to love my fellow beings: for example, orphaned children who suffer every day, not one of whom I have adopted. But I have loved people; I have loved children. And it seems that what happened between me and the children I chose to love was a version of what I was afraid would happen to the kitten. Human love is grossly flawed, and even when it isn’t, people routinely misunderstand it, reject it, use it or manipulate it. It is hard to protect a person you love from pain because people often choose pain; I am a person who often chooses pain. An animal will never choose pain; an animal can receive love far more easily than even a very young human. And so I thought it should be possible to shelter a kitten with love.

I made arrangements with the vet to get me a cat passport; Gattino endured the injection of an identifying microchip into his slim shoulder. Beatrice said she could not keep him in her house, and so I made arrangements for the vet to board him for the two weeks Peter and I traveled.

Peter arrived; Gattino looked at him and hid under the dresser. Peter crouched down and talked to him softly. Then he and I lay on the bed and held each other. In a flash, Gattino grasped the situation: the male had come. He was friendly. We could all be together now. He came onto the bed, sat on Peter’s chest and purred thunderously. He stayed on Peter’s chest all night.

We took him to the veterinarian the next day. Their kennel was not the quiet, cat-only quarters one finds at upscale American animal hospitals. It was a common area that smelled of disinfectant and fear. The vet put Gattino in a cage near that of a huge enraged dog that barked and growled, lunging against the door of its kennel. Gattino looked at me and began to cry. I cried too. The dog raged. There was a little bed in Gattino’s cage and he hid behind it, then defiantly lifted his head to face the gigantic growling; that is when I first saw that terrified but ready expression, that willingness to meet whatever was coming, regardless of its size or its ferocity.

When we left the vet I was crying absurdly hard. But I was not crying exclusively about the kitten, any more than my sister Jane was crying exclusively about euthanizing her old cat. At the time I didn’t realize it, but I was, among other things, crying about the children I once thought of as mine.

Caesar and his sister Natalia are now twelve and sixteen respectively. When we met them they were six and ten. We met him first. We met him through the Fresh Air Fund, an organization that brings poor urban children (nearly all of whom are black or Hispanic) up by bus to stay with country families (nearly all of whom are white). The Fresh Air Fund is an organization with an aura of uplift and hope about it, but its project is a difficult one that frankly reeks of pain. In addition to Caesar, we also hosted another little boy, a seven-year-old named Ezekial. Imagine that you are six or seven years old and that you are taken to a huge city bus terminal, herded onto buses with dozens of other kids, all of you with big name tags hung around your neck, driven for three hours to a completely foreign place, and presented to total strangers with whom you are going to live for two weeks. Add that these total strangers, even if they are not rich, have materially more than you could ever dream of, that they are much bigger than you and, since you are staying in their house, you are supposed to obey them. Add that they are white as sheets. Realize that even very young children ‘of color’ have often learned that white people are essentially the enemy. Wonder: who in God’s name thought this was a good idea?

We were aware of the race-class thing. But we thought we could override it. Because we wanted to love these children. I fantasized about serving them meals, reading to them at night, tucking them in. Peter fantasized about sports on the lawn, riding bikes together. You could say we were idealistic. You could say we were stupid. I don’t know what we were.

We were actually only supposed to have one, and that one was Ezekial. We got Caesar because the FAF called from the bus as it was on its way up, full of kids, and told us that his host family had pulled out at the last minute due to a death in the family, so could we take him? We said yes because we were worried about how we were going to entertain a single child with no available playmates; I made the FAF representative promise that if it didn’t work out, she would find a backup plan. Of course it didn’t work out. Of course there was no backup plan. The kids hated each other, or, more precisely, Ezekial hated Caesar. Caesar was younger and more vulnerable in every way; less confident, less verbal, possessed of no athletic skills. Ezekial was lithe, with muscular limbs and an ungiving facial symmetry that sometimes made his naturally expressive face cold and mask-like. Caesar was big and plump, with deep eyes and soft features that were so generous they seemed nearly smudged at the edges. Ezekial was a clever bully, merciless in his teasing, and Caesar could only respond by ineptly blustering, ‘Ima fuck you up!’

‘Look,’ I said, ‘you guys don’t have to like each other, but you have to get along. Deep down, don’t you want to get along?’

‘No!’ they screamed.

‘He’s ugly!’ added Ezekial.

‘Oh dry up Ezekial,’ I said,‘we’re all ugly, okay?’

‘Yeah,’ said Caesar, liking this idea very much. ‘We’re all ugly!’

‘No,’ said Ezekial, his voice dripping with malice, ‘you’re ugly.’

‘Try again,’ I said. ‘Can you get along?’

‘Okay,’ said Caesar. ‘I’ll get along with you Ezekial.’ And you could hear his gentle, generous nature in his voice. You could hear it, actually, even when he said, ‘Ima fuck you up!’ Gentleness sometimes expresses itself with the violence of pain or fear and so looks like aggression. Sometimes cruelty has a very charming smile.

‘No,’ said Ezekial, smiling. ‘I hate you.’

Caesar dropped his eyes.

*

We were in Florence for a week. It was beautiful, but crowded and hot, and I was too full of sadness and confusion to enjoy myself. Nearly every day I pestered the vet, calling to see how Gattino was. ‘He’s fine,’ they said. ‘The dog isn’t there any more. Your cat is playing.’ I wasn’t assuaged. I had nightmares; I had a nightmare that I had put my kitten into a burning oven, and then watched him hopelessly try to protect himself by curling into a ball; I cried to see it, but could not undo my action.

Peter preferred the clever, athletic Ezekial and Caesar knew it. I much preferred Caesar, but we had made our original commitment to Ezekial and to his mother, whom we had spoken with on the phone. So I called the FAF representative and asked her if she could find another host family for Caesar. ‘Oh great,’ she snapped. But she did come up with a place. It sounded good: a single woman, a former schoolteacher, experienced host of a boy she described as responsible and kind, not a bully. ‘But don’t tell him he’s going anywhere else,’ she said. ‘I’ll just pick him up and tell him he’s going to a pizza party. You can bring his stuff over later.’

I said, ‘Okay,’ but the idea didn’t sit right with me. So I took Caesar out to a park to tell him. Or rather I tried. I said, ‘You don’t like Ezekial do you?’ and he said, ‘No, I hate him.’ I asked if he would like to go stay at a house with another boy who would be nice to him, where they would have a pool and – ‘No,’ he said. ‘I want to stay with you and Peter.’ I couldn’t believe it – I did not realize how attached he had become. But he was adamant. We had the conversation three times, and none of those times did I have the courage to tell him he had no choice. I pushed him on the swing set and he cried, ‘Mary! Mary! Mary!’ And then I took him home and told Peter I had not been able to do it.

Peter told Ezekial to go into the other room and we sat Caesar down and told him he was leaving. ‘No,’ he said. ‘Send the other boy away.’

Ezekial came into the room.

‘Send him away!’ cried Caesar.

‘Ha ha,’ said Ezekial, ‘you go away!’

The FAF woman arrived. I told her what was happening. She said, ‘Why don’t you just let me handle this.’ And she did. She said, ‘Okay Caesar, it’s like this. You were supposed to go stay with another family but then somebody in that family died and you couldn’t go there.’

‘Somebody died?’ asked Caesar.

‘Yes, and Peter and Mary were kind enough to let you come stay with them for a little while and now it’s time to –’

‘I want to stay here!’ Caesar screamed and clung to the mattress.

‘Caesar,’ said the FAF woman. ‘I talked to your mother. She wants you to go.’

Caesar lifted his face and looked at her for a searching moment. ‘Lady,’ he said calmly, ‘you a liar.’ And she was. I’m sure of it. Caesar’s mother was almost impossible to get on the phone and she spoke no English.

This is probably why the FAF woman screamed, actually screamed, ‘How dare you call me a liar! Don’t you ever call an adult a liar!’

Caesar sobbed and crawled across the bed and clutched at the corner of the mattress; I crawled after him and tried to hold him. He cried, ‘You a liar too, Mary!’ and I fell back in shame.

The FAF lady then made a noble and transparently insincere offer: ‘Caesar,’ she said, ‘if you want, you can come stay with me and my family. We have a big farm and dogs and –’

He screamed, ‘I would never stay with you, lady! You’re gross! Your whole family is gross!’

I smiled with pure admiration for the child.

The woman cried, ‘Oh, I’m gross, am I!’ And he was taken down the stairs screaming, ‘They always send me away!’

Then Ezekial did something extraordinary. He threw his body across the stairs, grabbing the banister with both hands to block the exit. He began to whisper at Caesar, and I leaned in close, thinking, if he is saying something to comfort, I am going to stop this thing cold. But even as his body plainly said please don’t do this, his mouth spitefully whispered, ‘Ha ha! You go away! Ha ha!’

I stepped back and said to Caesar, ‘This is not your fault!’ He cried, ‘Then send the other boy away!’ Peter pried Ezekial off the banister and Caesar was carried out. I walked outside and watched as Peter put the sobbing little boy into the woman’s giant SUV. Behind me Ezekial was dancing behind the screen door, incoherently taunting me as he sobbed too, breathless with rage and remorse.

If gentleness can be brutish, cruelty can sometimes be so closely wound in with sensitivity and gentleness that it is hard to know which is what. Animals are not capable of this. That is why it is so much easier to love an animal. Ezekial loved animals; he was never cruel with them. Every time he entered the house, he greeted each of our cats with a special touch. Even the shy one, Tina, liked him and let him touch her. Caesar, on the other hand, was rough and disrespectful – and yet he wanted the cats to like him. One of the things he and Ezekial fought about was which of them Peter’s cat Bitey liked more.

On the third day in Florence I called Martha – the sister I later scolded for being hysterical about a cat – and asked for help. She said she would communicate psychically with Gattino. She said I needed to do it too. He needs reassurance,’ she said. ‘You need to tell him every day that you’re coming back.’

I know how foolish this sounds. I know how foolish it is. But I needed to reach for something with a loving touch. I needed to reach even if nothing was physically there within my grasp. I needed to reach even if I touched darkness and sorrow. And so I did it. I asked Peter to do it too. We would go to churches and kneel on pews and pray for Gattino. We were not alone; the pews were always full of people, old, young, rich and poor, of every nationality, all of them reaching, even if nothing was physically there. ‘Please comfort him, please help him,’ I asked. ‘He’s just a little thing.’ Because that was what touched me: not the big idea of tragedy, but the smallness and tenderness of this bright, lively creature. From Santa Annunziata, Santa Croce and Santa Maria Novella, we sent messages to and for our cat.

I went into the house to try and comfort Ezekial, who was sobbing that his mother didn’t love him. I said that wasn’t true, that she did love him, that I could hear it in her voice – and I meant it, I had heard it. But he said, ‘No, no, she hates me. That’s why she sent me here.’ I told him he was lovable and in a helpless way I meant that too. Ezekial was a little boy in an impossible situation he had no desire to be in, and who could only make it bearable by manipulating and trying to hurt anyone around him. He was also a little boy used to rough treatment, and my attempts at caring only made me a sucker in his eyes. As soon as I said ‘lovable’ he stopped crying on a dime and starting trying to get things out of me, most of which I mistakenly gave him.

Caesar was used to rough treatment too – but he was still looking for good treatment. When I went to visit him at his new host house, I expected him to be angry at me. He was in the pool when I came and as soon as he saw me, he began splashing towards me, shouting my name. I had bought him a life jacket so he would be more safe in the pool and he was thrilled by it; kind treatment did not make me a sucker in his eyes. He had too strong a heart for that.

But he got kicked out of the new host’s home anyway. Apparently he called her a bitch and threatened to cut her. I could see why she wouldn’t like that. I could also see why Caesar would have to let his anger out on somebody if he didn’t let it out on me.

Ezekial was with me when I got the call about Caesar’s being sent home. The FAF woman who told me said that Caesar had asked her if he was going back to his ‘real home, with Peter and Mary’. I must’ve looked pretty sick when I hung the phone up because Ezekial asked, ‘What’s wrong?’ I told him, ‘Caesar got sent home and I feel really sad.’ He said, ‘Oh.’ There was a moment of feeling between us – which meant that he had to throw a violent tantrum an hour later, in order to destroy that moment – a moment which could scarcely have felt good to him.

After Ezekial left I wrote a letter to Caesar’s mother. I told her that her son was a good boy, that it wasn’t his fault that he’d gotten sent home. I had someone translate it into Spanish for me, and then I copied it onto a card and sent it with some pictures I had taken of Caesar swimming. It came back: moved, address unknown. Peter told me that I should take the hint and stop trying to have any further contact. Other people thought so too. They thought I was acting out of guilt and I was. But I was acting out of something else too. I missed the little boy. I missed his deep eyes, his clumsiness, his generosity, his sweetness. I called the Fresh Air Fund. The first person I talked to wouldn’t give me any information. The next person gave me an address in East New York; she gave me a phone number too. I sent the letter again. I prayed the same way I did later for Gattino: ‘Spare him. Comfort him. Have mercy on this little person.’ And Caesar heard me – he did. When I called his house nearly two months after he’d been sent back home, he didn’t seem surprised at all.

When Peter and I returned to the veterinary hospital to claim Gattino, he purred at the sight of us. When we went back to Santa Maddalena, his little body tensed with recognition when he saw the room we had lived in together; then he relaxed and walked through it as if returning to a lost kingdom. My body relaxed too; I felt safe. I felt as if I had come through a kind of danger, or at least a kind of complex maze, and that I had discovered how to make sense of it.

The next day we went home. The trip was a two-hour ride to Florence, a flight to Milan, a layover, an eight-hour Atlantic flight, then another two-hour drive. At Florence Peter was told that because of an impossible bureaucratic problem with his ticket, he had to leave the terminal in Florence, get his bag and recheck it for the flight to Milan. The layover wasn’t long enough for him to recheck the bags and make it onto the flight with me, and the airline (Alitalia) haughtily informed him that there was no room on the next flight. I boarded the plane alone; Peter had to spent the night in Milan and buy a ticket on another airline; I didn’t find this out until I landed in New York with Gattino peering intrepidly from his carrier.

And Gattino was intrepid. He didn’t cry in the car, or on the plane, even though he’d had nearly nothing to eat since the night before. He settled in patiently, his slender forepaws stretched out regally before him, watching me with a calm, confidently up-raised head. He either napped in his carrier or sat in my lap, playing with me, with the person sitting next to me, with the little girl sitting across from me. If I’d let him, he would’ve wandered up and down the aisles with his tail up.

The first time I called Caesar, he asked about Bitey; he asked about his life jacket. We talked about those things for a while. Then I told him that I was sad when he left. He said, ‘Did you cry?’ And I said, ‘Yes. I cried.’ He was silent; I could feel his presence so intensely, like you feel a person next to you in the dark. I asked to talk to his mother; I had someone with me who could speak to her in Spanish, to ask her for permission to have contact with her son. I also spoke to his sister Natalia. Even before I met her, I could hear her beauty in her voice – curious, vibrant, expansive in its warmth and longing.

I sent them presents – books mostly, and toys when Caesar’s birthday came. I talked more to Natalia than to her brother; he was too young to talk for long on the phone. She reached out to me with her voice as if with her hand, and I held it. We talked about her trouble at school, her fears of the new neighborhood and movies she liked, which were mostly about girls becoming princesses. When Caesar talked to me, it was half-coherent stuff about cartoons and fantasies. But he could be suddenly very mature. ‘I want to tell you something,’ he said once. ‘I feel something but I don’t know what it is.’

I wanted to meet their mother; I very much wanted to see Caesar and meet his sister. Peter was reluctant because he considered the relationship inappropriate – but he was willing to do it for me. We went to East New York with a Spanish-speaking friend. We brought board games and cookies. Their mother kissed us on both cheeks and gave us candles. She said they could come to visit for Holy Week – Easter. Natalia said, ‘I’m so excited’; I said, ‘I am too.’

And I was. I was so excited I was nearly afraid. When Peter and I went into Manhattan to meet them at Penn Station, it seemed a miracle to see them there. As soon as we got to our house Caesar threw a tantrum on the stairs – the scene of his humiliation. But this time I could keep him, calm him and comfort him. I could make it okay, better than okay. Most of the visit was lovely. We have pictures in our photo album of the kids riding their bikes down the street on a beautiful spring day and painting Easter eggs; we have a picture of Natalia getting ready to mount a horse with an expression of mortal challenge on her face; we have another picture of her sitting atop the horse in a posture of utter triumph.

On the way back to New York on the train, Caesar asked, ‘Do you like me?’ I said, ‘Caesar, I not only like you, I love you.’ He looked at me levelly, and said, ‘Why?’ I thought a long moment. ‘I don’t know why yet,’ I said. ‘Sometimes you don’t know why you love people, you just do. One day I’ll know why and then I’ll tell you.’

When we introduced Gattino to the other cats we expected drama and hissing. There wasn’t much. He was tactful. He was gentle with the timid cats, Zuni and Tina, slowly approaching to touch noses, or following at a respectful distance, sometimes sitting near Tina and gazing at her calmly. He only teased and bedeviled the tough young one, Biscuit – and its true that she didn’t love him. But she accepted him.

Then things began to go wrong – little things at first. I discovered I’d lost my passport; Peter lost a necklace I’d given him; I lost the blue marble from Santa Maddalena. For the sixth summer in a row, Caesar came to visit us and it went badly. My sister Martha was told she was going to be laid off. We moved to a new house and discovered that the landlord had left old junk all over the house; the stove was broken and filled with nests of mice; one of the toilets was falling through the floor; windowpanes were broken.

But the cats loved it. Especially Gattino. The yard was spectacularly beautiful and wild, and when he turned six months old, we began letting him out for twenty minutes at a time, always with one of us in the yard with him. We wanted to make sure he was cautious and he was: he was afraid of cars, he showed no desire to go into the street, or really even out of the yard, which was large. We let him go out longer. Everything was fine. The house got cleaned up; we got a new stove. Somebody found Peter’s necklace and gave it back. Then late one afternoon I had to go out for a couple of hours. Peter wasn’t home. Gattino was in the yard with the other cats; I thought, ‘He’ll be okay.’ When I came back he was gone.

Because he had never gone near the road I didn’t think he would cross the street – and I thought if he had, he would be able to see his way back, since across the street was a level, low-cut field. So I looked behind our house, where there was a dorm in a wooded area, and to both sides of us. Because we had just moved in, I didn’t know the terrain and so it was hard to look in the dark – I could only see a jumble of foliage and buildings, houses, a nursery school and what I later realized was a deserted barn. I started to be afraid. Maybe that is why I thought I heard him speak to me, in the form of a very simple thought that entered my head, plaintively, as if from outside. It said, ‘I’m scared.’

I wish I had thought back: ‘Don’t worry. Stay where you are. I will find you.’ Instead I thought, ‘I’m scared too. I don’t know where you are.’ It is crazy to think that the course of events might’ve been changed if different sentences had appeared in my mind. But I think it anyway.

The next day I had to go into Manhattan because a friend was doing a public reading from her first new book in years. Peter looked for Gattino. Like me he did not look across the street; he simply didn’t think he would’ve gone there.

The second day we made posters and began putting them up in all the dorms, houses and campus buildings. We alerted campus security, who put out a mass email to everyone who had anything to do with the college.

The third night, just before I went to sleep, I thought I heard him again. ‘I’m lonely,’ he said.

The fifth night we got the call from a security guard saying that he saw a small, thin, one-eyed cat trying to forage in a garbage can outside a dorm. The call came at two in the morning and we didn’t hear it because the phone was turned down. The dorm was very close by; it was located across the street from us, on the other side of the field.

I walked across the field next day and realized something about it that I had not noticed before: from a human perspective it was flat enough to easily look across; from the perspective of a creature much lower to the ground, it was made of valleys and hills too big to see over.

Something I didn’t say correctly: I did not lose the blue marble from Santa Maddalena. I threw it away. When Peter lost his necklace I decided that the marble was actually bad luck. I took it out into a field and threw it away.

A friend offered to pay for me to see a psychic. He hadn’t seen her, he doesn’t see psychics. But a pretty girl he was flirting with had seen this psychic, and been very impressed by her; my friend wanted me to tell him what the psychic was like, I guess in order to get some sideways knowledge of the girl. So I made the appointment. She told me that Gattino was ‘in trouble’. She told me he was dying. She couldn’t tell me where he was, except that it was down in a gulley or ditch, someplace where the ground dropped down suddenly; water was nearby and there was something on the ground that crunched underfoot. Maybe I could find him. But maybe I wasn’t meant to. She thought maybe it was his ‘karmic path’ to ‘walk into the woods and close his eyes’, and, if that was so, that I shouldn’t interfere. On the other hand, she said, I might still find him if I looked in the places she described.

I told my friend that I was not impressed with the pretty girl’s choice of psychics. And then I went to the places she described and looked for Gattino. I went every day and every night. At the end of one of those nights, when I was about to go to sleep, words appeared in my head again. They were, ‘I’m dying’ and then ‘Goodbye.’ I got up and took a sleeping pill. Two hours later I woke with tears running down my face.

*

Who decides which relationships are appropriate and which are not? Which deaths are tragic and which are not? Who decides what is big and what is little? Is it a matter of numbers or physical mass or intelligence? If you are a little creature or a little person dying alone and in pain, you may not remember or know that you are little. If you are in enough pain you may not remember who or what you are; you may know only your suffering, which is immense. Who decides? What decides – common sense? Can common sense dictate such things? Common sense is an excellent guide to social structures – but does it ever have anything to do with who or what moves you?

After that first Easter visit, Caesar and Natalia came up for two weeks during the summer. We went biking and swimming and to the movies and the Dutchess County Fair. Natalia started taking horse-back riding lessons. At night she and I had a ritual of ‘walking at night’, during which we would walk around the neighborhood and talk intimately. She told me that she had lied to me when she’d said earlier that she was doing well in school; she admitted that she was failing. I asked her if she wanted to do better. She said yes. I asked if she would like me to help her with her homework on the phone at night, and she said, ‘Yes.’

Peter was primarily ‘in charge’ of Caesar – but they did not have a bond. Peter didn’t like the boy’s combination of neediness and aggression. The kid would hang on Peter and always want his attention – and if he didn’t get it, which he often did not, he would say something like, ‘When I get older I’m going to knock your teeth out.’ He said it like a joke, and he was after all a small child. But physically he wasn’t small; neither he nor his sister was small in that sense, and one took what they said seriously because of it. I took Caesar’s aggression seriously – but for a long time I forgave it. I forgave because for me the aggression and need translated almost on contact as longing for the pure affection he had been denied by circumstance, and outrage at the denial. His father had, after all, left him; his mother – who was in her mid-forties – worked long hours at a factory and so left the children alone often. When she got home she was usually too tired to do more than cook dinner; Caesar said she cursed him regularly. Both children believed she preferred her four grown kids living in the Dominican Republic to them.

But nonetheless she loved them, especially Caesar. You could see it in their bodies when they were together, see it in the way she looked at him when she greeted him as ‘my beautiful son’. She loved both children, and she beat them. She beat them rationally as punishment, and irrationally, seemingly just as a way of relating. Once when I was on the phone with Natalia, helping her write an essay, she said, ‘Just a minute, I need to get another pencil.’ She put the phone down, said something to her mother in a light, questioning voice – and was answered with violent shouts that turned into crashes and scuffling and Natalia sobbing before the phone was slammed into its cradle. The mother sometimes attacked the children as if she was a child herself, pulling Natalia’s hair or scratching her. She demeaned Natalia, continuously. Caesar she infantilized, bathing him and brushing his teeth for him even when he was nine years old; if Peter hadn’t insisted that he tie his own shoes he might never have learned how – his mother ordered Natalia to do it, and so did he.

Two social workers at their school told us they already knew about the beatings, or thought they did; Natalia would report being beaten, and then take it back, saying she’d been lying. If she had bruises, she refused to show them. One of the social workers believed the kids were being abused and thought they should be taken away from their mother; the other thought Natalia was a liar and felt sorry for the mother, whom she had known for years. ‘She loves those kids,’ said the woman. ‘She works her ass off for them.’

And they loved her, passionately; their self-esteem was completely bound up with her. And so we bit our tongues and tried not to speak critically to the children of their mother. We found a person who could speak Spanish to translate for us, and we tried to consult her about the kids whenever possible (her advice was usually something like: ‘Just punch him in the mouth’), to show respect for her in front of them, to work with the situation. We had the kids up for Christmas, Easter, sometimes on their birthdays, and always for at least a few days in the summer. We occasionally met them in the city too. I worked with Natalia on the phone, helping her read assigned books and write reports on them. I also hired a tutor for her, paying a college student to go out to Brooklyn once a month to give her math lessons. Her teacher said she was improving. Then other kids began to jeer at her for it, and she got into fights. But she didn’t talk about that. She would call me and cry and say she couldn’t do well in school because of her mother beating her. I said, ‘You don’t have control over your mother. You have control over yourself.’ I said, ‘Please; keep trying.’ She was quiet for a moment. She said, very calmly, ‘Mary, I don’t think I can.’ I said, ‘Just try.’ But I could hear that she could not. I could hear it in her voice. I can’t put into words why she could not. But I could hear it.

She kept doing her homework on the phone with me. She kept meeting the math tutor. But even though she did the assignments, she didn’t turn them in. She would say she had, that the teacher was lying, that the teacher had torn them up, that the teacher hated her. The teacher said she never saw the work.

I kept looking for Gattino. I didn’t think in particular about the children while I looked for him. I barely thought at all. I tried to feel the earth, the sky, the trees and wet, frozen stubble of ground. But I couldn’t feel anything but sad. Once when I was driving to a shelter to check if he had been turned in, I heard a story on the radio about Blackwater contractors shooting into a crowd of Iraqi civilians. They killed a young man, a medical student, who had gotten out of his car. When his mother leaped from the car to hold his body, they killed her. I hear stories like this every day, and I realize they are terrible stories. But I don’t feel anything about them, not really. When I heard this one, my heart felt so torn open I had to pull off the road until I could get control of my emotions.

It was the loss of the cat that had made this happen; his very smallness and lack of objective consequence had made the tearing open possible. I don’t know why this should be true. But I am sure it is true.

True not just of my heart; my mind also tore. I called another psychic, a pet psychic, and asked her about Gattino. She told me he had died, probably of kidney failure after drinking something toxic. She said he had suffered. I called another one. She said he had died, but that he hadn’t suffered, that he had ‘curled up as if he were going to sleep’. I began asking random people if they had any ‘psychic feeling’ about the cat; I am still amazed at how many claimed that they did. Some of them were friends, some were acquaintances, some were complete strangers: a stranger, an innkeeper in Austin, told me that he was sicker than I realized, and that he had gone away to die in order to spare me any suffering; she said that he loved me. Then she put her arms around me and made purring sounds – and I made them back! An acquaintance, a taciturn and generally unfriendly woman who works in a stable, and whom I would not have thought to ask for psychic input, looked at the poster I showed her and her partner, and remarked in a low voice, just as I was about to walk away, ‘For whatever it’s worth, I don’t think your cat’s dead.’ She thought he was living in or under a white house with a lot of walkways around it. It sounded like a description of half the dorms on campus.

And so, in the middle of January I put another round of posters up on campus and in mailboxes. I started getting calls almost immediately from people saying that they had seen a small one-eyed cat. I started leaving food in the places he was supposed to have been, to keep him there. I also left scraps of my clothes near the food, so he might catch my scent and remember me. I left food in our backyard. I collected turds and piss clumps from the litter boxes and scattered them in our yard so that he might catch the scent of our other cats and be guided home by it. I collected a whole shopping bag of turds and piss and then went out late one night to make a trail of it from the far edge of the field to our house. The snow was up to my calves and it took me almost an hour to get through it, diligently strewing used litter in the path of my footsteps.

I asked Peter if he thought I was crazy. He said that sometimes he did think that. But then he thought of friends of his whose twin daughters had recently died of a rare skin disease called recessive dystrophic epidermylosis. When the girls were born, their parents were told they should put them in an institution. When they insisted on taking them home, the doctors just shrugged and gave them some bandages. Nothing was known about home care; the parents had to learn it all themselves. They devoted themselves to the care of their children, and they gave them nearly normal lives; in spite of the excruciating pain involved in almost every ordinary activity, including eating, the girls played sports, went to college, flirted online and had boyfriends. They hoped for a cure until they died at twenty-seven. Their parents worked right up until the end to make their lives as good or at least as unpainful as possible. ‘We would’ve done anything,’ said their mother. ‘If someone had told us it would help to smear ourselves with shit and roll in the yard, we would’ve done it.’

‘But they didn’t actually do it,’ I said.

‘Well,’ said Peter, ‘no one told them to.’

Because Natalia said she was afraid to go to the public junior high school, we paid for her and her brother to go to Catholic school. Caesar did okay, she got kicked out in a couple of months. Her mother laughed bitterly. She said, ‘Natalia will always cause trouble.’ I said, ‘I still believe in her.’ There was incredulous silence on the other end of the phone.

That summer, we sent them to a camp that was supposed to be great for troubled kids, and it was great, especially for Natalia. She excelled, the counselors loved her and invited her to participate in their year-long Teen Leadership program, which provided group phone calls with counselors and other kids, tutoring in school and weekend trips up to the camp every month. Natalia was thrilled, and when we returned her to her mother we showed her the pictures of Natalia at camp, getting along with everybody and not causing trouble. Her mother looked at the pictures and literally dropped them on the ground.

Natalia made the first two trips to camp and then stopped showing up. She stopped participating in the group phone calls. She stayed out all night and skipped school. She said it was because her mother beat her. Her mother said it was because she wanted to have sex and do drugs.

When she came up to visit for Christmas we had a fight; afterward I tried to talk to her. She said, ‘I don’t care. I don’t care about nothing.’ I said I doubted that was true. She said, ‘It is true. It’s always been true.’ And I felt her relief in saying it. ‘All right,’ I said. ‘It might be true sometimes, but not all the time; almost everybody cares about something, sometime.’ She looked at me sullenly; she did not disagree. ‘But,’ I said, ‘if you walk around acting like you don’t care for long enough, people will start to believe you. If you really don’t care, then people who do care will leave your life and people who don’t care will come in to it. And if that happens, you will find yourself in a very terrible place.’ As I spoke her face slowly opened; slowly, her sullenness revealed fear. I kissed her and said, ‘It doesn’t have to be that way.’ A few months later she ran away from home.

Caesar was nine when his sister ran away, and I could sense him watching her with very wide eyes. He joined his mother in condemning her, but even when he did, I could still hear affection for her in his voice. He loved his family – but he loved me too. I could talk to him about anything, about dreams, heaven and hell, what made a person evil and why a picture was good or bad. When he noticed the picture of my father in the glassed-in cabinet that functions as a sort of shrine, he wanted to know about him. I told him that my father was orphaned by the death of his mother when he was nine, followed by the death of his father a year later. Then his dog died. Still, when the world war broke out, my father wanted to enlist. He joined the war at Anzio, one of the most terrible battles. Caesar said, ‘I feel bad for your father. But I don’t feel sorry for him. Because he sounds like a terrific person.’ Later, when Peter asked if Caesar had ever had an imaginary friend, he said, ‘I didn’t before but I do now. My imaginary friend is Mary’s father.’

When my father was dying I asked him something. I did not really ask him; I don’t think he was conscious and I whispered the question rather than spoke it. But nonetheless it was a serious question. ‘Daddy,’ I said, ‘tell me what you suffered. Tell me what it was like for you.’ I could never have asked him in life. But I believed that on the verge of death he could ‘hear’ my whispered words. And slowly, over a period of time, I believe I have been answered, at least in part. I felt that I was hearing part of the answer while I was out looking for my cat, when it was so cold and so late no one else was around. It occurred to me then that the loss of the cat was in fact a merciful way for me to have my question answered.

Both my sisters and I sat with my father when he was dying; we all took care of him with the help of a hospice worker who stopped by every day. But Martha was alone with him with he died. She said that she had felt death come into the room. She said that death felt very gentle. Later she told us that she felt and even saw terrible things before he died. But she seemed at peace about witnessing his death.

When Martha returned home she had to go right back to work. She was not close to the people she worked with and they were not ideal confidants. But she needed to talk to someone and so she did. When she described my father’s life to a coworker, he found it absurd that Martha seemed to place as much emphasis on the death of my father’s dog as she did on the death of his parents, and he spoke to her coolly. ‘I love dogs,’ he said. ‘I’m sad when a dog dies. But no dog should ever be compared to family.’

When I was out looking for the cat, so late that no one else was around, I remembered this story, and I wished I had been with my sister when her coworker spoke to her that way. I would have said, ‘Imagine you are a nine-year-old boy and you have lost your mother. You are in shock and because you are in shock you are reduced to a little animal who knows its survival is in danger. So you say to yourself, “Okay, I don’t have a mom. I can deal with that.” And then the next year your father dies. You think, “a’ight. I don’t have a dad either. I can deal with that too.” Then your dog dies. And you think, “Not even a dog? I can’t even have a dog?” I would’ve said, “Of course the dog didn’t mean as much to him as his parents did, you moron. His parents meant so much to him, he could not afford to feel their loss. The dog he could feel, and through the door of that feeling came everything else.” ’

The figurative loss of ‘my’ children and the loss of my cat were minor compared to what my father lost. That is why it was a merciful loss; it was enough to give me a taste of what my father felt, and a taste was all I could bear. I had not understood this before. The family myth was that my father was weak, neurotic, a little boy unable to emotionally grow up. There was some reality to this perception. But the bigger reality is this: my father was strong, much stronger than I am. If I had experienced what he had experienced by the age of nine, it would’ve broken me several times over. What happened to him hurt him, and badly. It did not break him. He raised a family and held a job. He was brutally unhappy and sometimes he behaved miserably towards his wife and children. But he never stopped. He never broke. Until the very end.

Caesar once asked me if he could come live with us. I said I didn’t think he really wanted that; for one thing, we would make him do his homework constantly. He replied that he would. I said I thought he would miss his mother too much. He hesitated, then replied that maybe he would. I said, ‘Besides, we wouldn’t hit you when you were bad, and then you wouldn’t know what to do.’

He was silent for a moment. Then he said, ‘You’re right.’

‘Why do you think that is?’ I asked.

He thought for a long time; I could tell that he was thinking hard. ‘I don’t know. Why do you think that is?’

‘Honey,’ I said. ‘I don’t know the answer to that. Nobody knows the answer to that. If you could answer that, you would make a million dollars.’

Maybe it was a strange conversation to have with a ten-year-old. But I wanted him to think about it even if he would never find the answer. If he could think about why he needed to be hit, then he would know that the need to be hit wasn’t him, but something separate, about which he might have thoughts. I’m not sure this would make any difference. Once, during a fight with him about his throwing rocks at some ducks, I said, ‘Do you want me to treat you like that, just because I’m bigger? Do you want me to hit you?’

He said, ‘Yeah, hit me, go on.’ He said it a couple of times.

I didn’t. I turned and walked away. But for a moment I was tempted. I was tempted partly by frustration. I was also tempted by the force of his need.

These children, you see, were not weak people. They were troubled, at risk, disadvantaged, they suffered from racism, from low self-esteem – anything you like. Socially, that is in terms of money and privilege, I was their superior in every way. But in a bigger, harder to articulate way, they were, in spite of their youth, at least my equals, if not superior to me. Superior not because of anything innate, but because of their exposure to brutal, impossibly complex social forces which they were made to negotiate every day of their lives. Sometimes, when Natalia and I were watching a movie together, she would lean against my shoulder and I would acutely feel that my smaller body, my bony shoulder, was not big enough to bear her weight. I would feel, I am simply not big enough to give this girl what she needs. I had moments of great joy with them; watching them unwrap their presents under the Christmas tree, making them sandwiches, watching Natalia on a horse or Caesar learning how to swim. But I often felt inadequate, wrong, unable to affect them, frustrated, mismatched – at best like a well-intentioned mouse crazily trying to chew two lion cubs out of a massive double net cast upon them by vast powers beyond its tiny vision.

They knew this, I’m sure. They no doubt sometimes felt scorn for my feelings of ineptitude, and also for my attempts to act confident in spite of them, to be inspiring and optimistic when I barely knew how. But they were also supportive and, on occasion, very kind. When Peter or I was trying to do something and it wasn’t working out easily – put dinner on the table, find the petting zoo, get our erratic VCR to play – the kids would sometimes go very quiet and we could feel them unite in their appreciation of our efforts, subtly throwing their goodwill behind us. Sometimes, I felt their generosity even when they weren’t there, as if they were standing behind me, their hands on my shoulders. I am afraid of flying, and I remember one panic-stricken moment at an airport, when my own mind became too much for me to bear; the only way for me to calm myself was to remember Natalia riding a horse, sitting up straight in the saddle and smiling.

After Gattino had been gone almost two months, I visited a woman whose husband had died three years earlier. She was still deep in grief, and her grief accentuated her propensity for mysticism; to her I wondered if the blue marble which had so magically appeared to me in Italy, and which I then threw away, might have something to do with the cat’s disappearance. Instead of trying to talk common sense to me, the grieving woman said she knew of a great psychic who might be able to answer that question. I said, No, I did not want to pay any more psychics. The woman said that this psychic was a friend of hers, and that she would just ask her the question, that it need not be a full reading.

A few weeks later I received an email from this psychic which said that the blue marble was not a curse or an omen of any kind. However, its physical movement across the floor had been the by-product of a deliberate psychic energy directed towards me by a young man at Santa Maddalena; this young man was a practitioner of magic, and he had recognized me as a kindred spirit, a person in need of love and capable of fully expressed love. He had wished me well, and it was the force of his wish that had set the marble rolling. It had nothing to do with Gattino, but became bound up with the circumstances of the cat, which was interesting to the psychic because the marble was to her symbolic of an eye, and the kitten was missing an eye.

She added that Gattino was not dead; she said that he had been picked up by a ‘traveler’ who was well acquainted with the system of cat shelters and havens all over the state. This traveler had taken my cat to one of these shelters, where he was at this moment being well cared for. If I wanted to find him, she suggested that I contact every such shelter within a fifty-mile radius.

This information would, she said, cost me one hundred dollars.

If someone had told me to smear shit on myself and roll in the yard, if that person was a cat expert and made a convincing case that, yes, doing so could result in the return of my cat, I probably would’ve done it. I did not consider this pathetic susceptibility ‘magical thinking’. I didn’t consider it very different from any other kind of thinking. It was more that the known, visible order of things had become unacceptable to me – senseless, actually – because it was too violently at odds with the needs of my disordered mind. Other kinds of order began to become visible to me, to bleed through and knit together the broken order of what had previously been known. I still don’t know if this cobbled reality was completely illusory, an act of desperate will – or if it was an inept and partial interpretation of something real, something bigger than what I could readily see. In this way my connective symbols – the marble, the things different psychics said to me – were similar to religious statues and icons that people pray to, or parade through the street with, or wear around their necks. Except that the statues and icons are also artful creations, sometimes beautiful ones. My symbols were not beautiful, they were stupid and trite. They were related to the symbols of religion as a deformed and retarded child might be the distant cousin of a beautiful prince. But they were related nonetheless.

I paid the money. I called, and Peter helped me call, all the cat shelters within a fifty-mile radius. Many of the shelters I contacted asked me to send them a picture of Gattino along with my contact information which they posted on their internet sites; I immediately began getting responses from people who thought they might’ve seen him. I also got responses from businesses devoted to the rescue of hopelessly lost cats, one of which included a private detective willing to fly to your state with his tracking dogs, a smiling pit bull and a vigilant poodle depicted nobly flanking their owner on the site. The superior quality of these businesses was attested to by customer after satisfied customer on each of the sites: ‘At first I was skeptical. But as soon as I opened my front door and saw Butch and his gentle tracking dogs, I knew . . .’

I also received an email from someone who appeared barely able to write English, but who claimed to have seen someone named ‘Samuel’ find a cat outside of a ‘community center’, to have talked with Samuel about seeing an ad for my cat online and to have gotten an email address from Samuel, if I wanted to contact him. ‘Samuel’ of course wanted to see a picture of Gattino to be sure he had the right cat; on receiving a photo he said that yes, he definitely had my cat. He went on to say that, like me, he had fallen in love with Gattino and taken him home to Nigeria, but if only I would send the airfare, he would return my darling. Upon googling the first few lines of ‘Samuel’s’ note, I found an outraged warning about him from someone who had paid the fee and never saw her cat.

*

This world is the only reality available to us, and if we do not love it in all its terror, we are sure to end up loving the ‘imaginary,’ our own dreams and self-deceits, the utopias of politicians, or the futile promises of future reward and consolation which the misled blasphemously call ‘religion.’

This is Leslie Fiedler, writing about Simone Weil. When I read it I thought, Yes, that is me: deep in dreams of marbles, omens and psychics, hoping that something will have pity on me and my cat. But can one always tell what is imaginary and what isn’t? To be ‘sentimental’ is scorned by intelligent people as false, but the word is one short syllable away from ‘sentiment’, that is, feeling. False feeling is so blended with real feeling in human life, I wonder if anyone can always tell them apart, or know when one may be hiding in the other. When my father was dying he cried out for people who were not there, in a voice that we did not recognize as his. One of these times he said, ‘I want my mama.’ When we heard this, Jan§e and I froze; both of us were asking ourselves, should we pretend to be his mother? It was Martha who knew what to do; she held his hand and sang to him. She sang him a lullaby, and he calmed. He thought his mother was there. Was this a dream, a self-deceit?

I called the three young men who had been at or near Santa Maddalena with me, to find out if any of them practiced magic. The first one I called was a medical student who had also written an internationally acclaimed book about a child soldier in West Africa. I emailed him first and asked if we could talk on the phone. I wonder what he thought was coming. It could scarcely have been what came: ‘I know this is a peculiar question,’ I asked. ‘But do you practice anything that anyone could call magic?’

There was a long silence. ‘Do you mean literally?’ he asked.

I thought about it. ‘Yes,’ I said. ‘I think I do.’

The silence that followed was so baffled that I broke down and explained why I was asking.

‘Well,’ he said, ‘I pray. Do you think that counts?’

I said, To me it could. But I don’t think that’s what the lady meant. He was very sympathetic about Gattino. He said he would pray for me to find him. I thanked him and called someone else.

When my father was alive, he and Martha were distant, uncomprehending, nearly hostile. He was cold to her, and she felt rejected by him. As he became more and more unhappy with age and was eventually rejected by my mother, he tried to reach out to Martha. But the pattern was too set. During one of our last Christmas visits to him, I saw my father and Martha act out a scene which looked like a strange imitation of a cruel game between a girl who is madly in love with an indifferent boy, and the boy himself. She kept asking him over and over again, Did he like the present she had gotten him? Did he really, really like it? Would he use it? Did he want to try it out now? And he responded stiffly, irritably, with increasing distance. She behaved as if she wanted to win his love, but she was playing the loser so aggressively that it was almost impossible for him to respond with love, or to respond at all. What was the real feeling here? What was the dream or the self-deceit? Something real was happening, and it was terrible to see. But it was so disguised that it is hard to say what it actually was.

Still, as he lay dying, she was the one who knew to hold his hand; to sing to him.

The second young man I called, a Hungarian writer I had met outside of Santa Maddalena, answered quite differently from the first. ‘I have powers,’ he said intensely, ‘but I have never been taught how to use them very well. If I made something move, it would be something big, like a building. But a marble – I’m not that good. To move something that small would require more refinement than I possess.’

At least this conversation made me smile; when I repeated it at a party, I meant to amuse people – but it actually offended someone. ‘He sounds like an idiot!’ said a film producer who happened to overhear me. ‘There’s nothing charming in that, he just sounds really, really stupid.’ And then the producer, the voice of normalcy and intelligence, began describing to me his latest idea for a comedy: A man who married very young is, at thirty, full of wanderlust. His wife goes off for a trip alone, and he finds himself in the presence of a beautiful young woman who wants him. ‘Finally, she gets him alone and she takes off her shirt, and she’s got incredible tits, really big tits, and they’re perfect, the most beautiful big tits you’ve ever seen! But he says no and –’

I laughed, almost hysterically. Yes, it was a comedy, and a deeper one than its creator knew, to have at its dramatic center the rejection of beautiful naked breasts. Of course the hero rejects these breasts in the name of faithfulness, and rationally all is well. But if one mutes the trite music of the story and watches the action as sketched by the producer, one sees a different, more stark play. Whether it’s a comedy or a drama, a titillating image or a perverse one depends on what you feel about naked breasts, which, in the most fundamental symbolic language, translate as nurture, love and vulnerability. My sister was offering my father love, in a form he could not accept, just as he, with increasing desperation, offered my mother love she could not accept or even recognize. In each offering purity and perversity made a strange pattern; each rejection made the pattern more complete.

If my father had acted differently towards Martha, it is possible that he could’ve broken this pattern. Because he was the parent, it’s possible that the burden was on him to do so. But I don’t think he could. He wasn’t sophisticated when it came to his emotions. His emotions were too raw for sophistication.

When I was thirty-two, I tried to break the pattern. I was visiting home and my father was having a temper tantrum, which meant on this occasion that he was yelling at my mother about her failings. He had done this for years, and normally the entire family would be silent and wait for him to tire himself out. This time I did not. I yelled at him. I told him I was tired of listening to him complain and blame everything on someone else. I expected him to yell back at me; in the past, I might’ve expected him to hit me. But he didn’t. He turned and walked away. I followed him, still yelling. Finally I yelled, ‘I am sorry for talking to you this way. I’m doing it because I want to have a real relationship with you. Do you want a real relationship with me?’

He said, ‘No,’ and shut his bedroom door in my face.

I felt bad. I also felt vindicated. I had been right and he had been wrong. Even so, I apologized the next day, and we talked, a little. He did not take back his words. That made me even more right. It made me right to emotionally shut the door on him.

I repeated this conversation to an older man, a friend who is also a father. He laughed and said, ‘I would’ve said “no” too if I were him.’

I asked why. I don’t remember what he said. I came away with the impression that my friend found the language I used too corny or therapeutic. And it was. Certainly my father would’ve found it so. But I don’t think that’s the only reason he walked away. If my language was a cliché, it was also heartfelt and naked. That kind of sudden nakedness, without even a posture of elegance, would’ve been a kind of violence to my father. It would’ve touched him forcefully in a place he had spent his life guarding. To say ‘yes’ would’ve allowed too much of that force in too deeply. Saying ‘no’ was a way of being faithful to the guarded place.

My father continued to throw tantrums and blame people for his suffering. A little while after I asked him if he wanted a real relationship with me, I wrote a letter telling him how angry I was with him for acting that way. Before I sent it, I told my mother about it. She said it would really hurt him. She said, ‘He told me, “Mary and I have a real relationship.” At the time I thought, How sad. Now I think he was right. Our relationship was real. What I wanted it to be was ideal.

Because a security guard named Gino claimed to have seen Gattino months after he disappeared, both Peter and I began to believe that he had somehow found a place to survive, even though the temperatures had sometimes gone down to freezing, even though it must’ve been hard to get enough to eat. I began draping the bushes of our house with sweaty clothes, hoping that the wind would carry the scent to him, and that he would be able to find his way back. We continued to put food out in sheltered places near parking areas; in addition, we began to ‘stake out’ these areas at night, sitting in our car with the headlights trained on the food. We saw at least two cats come to eat – both were gray tabbies, but big ones that surely no one could mistake for the delicate cat depicted on our poster. Only once, Peter saw a very small, thin cat who could’ve been ours, but he couldn’t get a good look because it was slinking under parked cars. It was about to emerge into the open when a noisy crowd of students came by and it darted away back under the cars.

The very act of doing these things – waiting in the parking lots, draping the bushes with clothing – made me feel that Gattino was still there.

Before I met Gattino, before I went to Italy, I talked with Caesar on the phone, and during that conversation he asked why I sent his mother money. I should have said, because I love you and I want to help her take care of you. Instead I said, ‘Because when I first met your mother and she told me she made six dollars and forty cents an hour, I felt ashamed as an American. I felt like she deserved more support for coming here and trying to get a better life.’

He said, ‘What you’re saying is really fucked up.’

I said, ‘Why?’

He said, ‘I don’t know, it just is.’

I said, ‘Put words on it. Try.’

He said, ‘I can’t.’

I said, ‘Yes you can. Why is what I’m saying fucked up?

He said, ‘Because it’s good enough that she came here to get a better life.’

I said, ‘I agree. But she should be acknowledged. I have a hard job and sometimes I hate it, but I get acknowledged and she should too. And somebody besides me should do it, but nobody is, so I am.’

He said, ‘People are acknowledging her. She makes more money now.’

I said, ‘That’s good. But it still should be more.’

He said, ‘You act like you feel sorry for her.’

I said, ‘I do, so what? Sometimes I feel sorry for Peter, sometimes I feel sorry for myself. There’s no shame in that.’

He said, ‘But you talk about my mom like she’s some kind of freak.’

I said, ‘I don’t think that.’

He said, ‘You talk about her like you think you’re better than her.’

And for a moment I was silent. Because I do think that – rather, I feel it. Before God, as souls, I don’t feel it. But socially, as creatures of this earth, I do. I’m wrong to feel it. But I do feel it. I feel it partly because of things Caesar and Natalia have told me.

He heard my hesitation and he began to cry. And I so I lied to him. Of course he knew I lied.

He said, ‘For the first time I feel ashamed of my family.’

I said I was sorry; I tried to reassure him. He asked me if I would take money from someone who thought they were better than me and I said, ‘Frankly, yes. If I needed the money I would take as much as I could, and I would say to myself, “Fuck you for thinking you’re better than me.” ’

Passionately, he said he would never, ever do that.

I snapped, ‘Don’t be so sure about that. You don’t know yet.’

He stopped crying.

I said, ‘Caesar, this is really hard. Do you think we can get through it?’

He said, ‘I don’t know.’ Then, ‘Yes.’

I asked him if he remembered the time on the train when he was only seven, when he asked me why I loved him and I said I didn’t know yet. ‘Now I know why,’ I said. ‘This is why. You’re not somebody who just wants to hear nice bullshit. You care. You want to know what’s real. I love you for that.’

This was the truth. But sometimes even loving truth isn’t enough. He said he was sorry he’d bothered me, and that he was tired. I asked him if he still felt mad at me. He hesitated and then said, ‘No. Inside, I am not mad at you, Mary.’

For months after Gattino disappeared, I still dreamed of him at least once a week. I would dream that I was standing in the yard calling him, like I had before he’d disappeared, and he’d come to me the way he had come in reality: running with his tail up, leaping slightly in his eagerness, leaping finally into my lap. Often in the dream he didn’t look like himself; often I blended him with other cats I have had in the past. In one dream I blended him with Caesar. In this dream, Caesar and I were having an argument, and I got so angry I opened my mouth, threatening to bite him. He opened his mouth too, in counter-threat. And when he did that, I saw that he had the small, sharp teeth of a kitten.

When we came back from Italy, Caesar came to visit. We were tired and packing to move. We did not have as much energy as we usually had for him; he felt that immediately and resented it. He said, ‘You’ve changed.’ And he became volatile and hostile, behavior which had a very different quality at the age of twelve than it had when he was seven. The second day he was with us he told Peter, ‘I want to cut off your nuts’; I thought Peter would knock him down the stairs. Some days later he told me I didn’t have any kids because I went to the vet and ‘got fixed’; I answered rationally, but inside, for the first time, my feelings for him went dead. That night after he went to bed, he started screaming that he couldn’t breathe. I gave him his inhaler and rubbed his chest. For over an hour he continued to scream and to force himself to cough, loudly and dramatically. I went in the room and sat with him. I told him I knew he was faking the asthma, and that I also knew it was hard to be with us and that the visit wasn’t going right. I told him I was having a hard time sleeping too and that I was really tired, which was part of why I couldn’t be as present as I’d like. I put my hand on his stomach and told him to breathe there. He did. We talked about the Harry Potter movie we had seen the night before. We talked about the idea of an alternate universe, and what might be going on in it right now. I felt connected to him again. He closed his eyes and began to breathe evenly. I left his room at one o’clock. He woke me up at six the next morning, demanding that I get up and help him turn on the shower.

In March, four months after Gattino disappeared, I got a call at three in the morning from Gino the security guard who said he had just seen him in one of the parking lots. I put my coat on over my pajamas, got in the car and was there within minutes. Gino and another guard were excitedly pacing around with flashlights, pointing at the dim figure of a cat under the last car at the end of a row of cars. When I appeared the cat bolted.

‘There he goes!’ cried Gino. And he shone his flashlight on the obese tabby we had been seeing for months.

‘That can’t be him,’ said the other guard. ‘That cat has two eyes.’

‘No he doesn’t!’ insisted Gino. ‘I shined my light on him and I saw!’

A few nights later I spoke to another security guard, a reticent older man who had once told me that he’d seen my cat. I asked him, when had he last seen Gattino? He said it had been three months ago – maybe longer. ‘I haven’t seen many cats lately,’ he said. ‘I’ll tell you what I have seen though. There’s a huge bobcat, all over campus late at night. That and a lot of coyotes.’

His meaning was clear. I didn’t say much of anything. I thought, At least it’s a death an animal would understand.