A little over ten years ago, in October 2008, the English physicist Freeman Dyson confessed that he was incapable of hearing a particular song by Monique Morelli – ‘La Ville Morte’ – without suddenly being overcome by an outburst of emotion that he found completely inexplicable. The ballad, interpreted by an aching Morelli and accompanied by the wails of an accordion, is full of haunting images: As we walked into the Dead City / I held Margot by the hand / The eternal morning sun / Bathed us in its dying light / We walked from one ruin to the next / Through bombed out streets, from door to door / Flung open like the lids of coffins. No matter how many times Dyson played his copy of the recording, his eyes would fill with tears, so much so that he became ashamed of listening to it in front of others, and would only indulge in the music by himself, every now and again, when he felt up to it. What made his emotional response even more baffling was the fact that he could speak almost no French, and that before asking a friend to translate it for him, he had but the haziest idea of what the song was really about, and felt no solace when he achieved a fuller understanding. After years of puzzling over it, he became convinced that there was something in those specific verses, written by the French poet and novelist Pierre Mac Orlan, that resonated in the deepest substrate of his unconscious memory, as if Monique were not really singing for the living but for the countless souls of the departed whose corpses pile, unseen and forgotten, beneath our feet. Dyson finally found a plausible explanation for his melancholy in a short essay entitled ‘The Empty City Archetype’, included in the collected works of the Russian mathematician, Yuri I. Manin, Mathematics as Metaphor. In his essay, Manin speaks of the empty city as a ‘form of society devoid of its soul and expecting no infusion; a cadaver which had never been a live body; a Golem whose life itself is death’. He likens the effect of this archetype on our psyche to the nebulous feelings of loss that come over us when we chance upon an abandoned beehive, or watch the endless flows of water in Andrei Tarkovsky’s movies, that Russian genius so obsessed with capturing images of our dreams that he submerged himself, his wife, and his crew in rivers of poisonous chemicals to make Stalker, the movie that would eventually cost him his life, as the luscious interplay of iridescent streams that he caught in fleeting frames of celluloid were the products of toxic refuse from several abandoned factories, which likely caused the cancerous growth that ravaged his lungs and killed him in 1986, months after he had turned fifty-four, and that would also claim the lives of Larisa, his wife, and of his signature actor, Anatoly Solonitsyn, smitten by the very same illness. In Stalker, an enormous extension of land – known only as The Zone – has been contaminated and made unliveable by an invisible force that not only infects people’s bodies and minds but perhaps even their very souls. The region has been cordoned off by armed government forces; nonetheless, a small group of desperate men and women are irresistibly drawn there, like moths to a radioactive flame, following a rumour that says that deep inside The Zone, in the strangest and most alien part of that territory, there is a small and seemingly commonplace room that has the power to grant the wishes of anyone who manages to step inside it. To traverse the dangers of The Zone, seekers of the room must hire professional guides called Stalkers, who help them navigate its deranged landscapes, abandoned ruins and disintegrating structures where vegetation has quickly advanced and reclaimed the land, growing over the caterpillar tracks of derelict tanks, covering the facades of factories, schools, hospitals and many other half-ruined buildings made unrecognizable by disuse and decay. There, the rules of reality have somehow been suspended; time flows in strange loops, memories and dreams become manifest, nightmares are as real and terrible as waking life. The scenery is infused by a heady melancholy that preys alike upon the Stalkers and those who strive to make their longings come true. For The Zone is clearly animated, subsumed with something that resembles human consciousness, even though it is completely uninhabited and hostile, a stubborn revenant that somehow manages to resist the merciless passage of time and that, like the images of past horrors conjured by the archetype of The Empty City, refuses to fade away. Manin explains the ubiquity of this archetype in our collective memory as the product of the accumulated experiences of countless peoples that, throughout deepest history, have suddenly chanced upon the remains of an ancient and forgotten temple crumbling to dust among the desert sands, buried under the lush trees of impenetrable jungles or hidden atop the highest and most inaccessible mountain valleys, ruins built at such a colossal scale that they surely must have been the abode of gods or creatures from another planet, haunted spaces which were to be feared and avoided as the Saxons shunned the stone walls of Roman buildings, which they regarded as the heritage of mythological giants and never once occupied. The dead city exists since time immemorial; it dates back to the dawn of civilization, when the first human beings began to crowd together in settlements that grew ever larger, and which, as they thrived and flourished, goaded others to assemble armies to raid, pillage and destroy them. The Empty City archetype is a mental construct distilled from the agony of countless real communities. It is the afterglow left by the fires that razed their buildings to the ground, the still-felt shivers of the earthquakes that tore their foundations apart, the pangs of hunger brought on by drought, the scars of the plagues which emptied them overnight. But Manin warns that these phantom images, though faint and fading, are neither passive nor neutral: on the contrary, they nourish our darkest and most violent desires. A deep longing for dissolution. A passionate craving to see the destruction of all that we know. A need to cleanse this world from the stains of humanity, to free our planet not just from the demons of progress but from all the evils which arise from our accursed nature. Our collective unconscious is not inert mental baggage, it is an irrational impulse that beckons us towards death and destruction. Indifferent to the dreams of reason, the unconscious is not a force leading us to integration and wholeness, rather it is a cohort of madness, folly and chaos, a siren song that we must vehemently resist. ‘Only by fostering the collective consciousness’ – Manin writes – ‘can we counteract that destructive potential. Otherwise The Empty City will be our last abode’.

The protagonist of the song that so mesmerized Freeman Dyson is an old soldier, part of an army of occupation. The unnamed fighter is not awake in the song but asleep and dreaming: he sees himself walking through the rubble and dust of a conquered city, holding his wife’s hand as they survey the dark ruins all around them. They pass bombed-out houses, burnt cars, open graves and the twisted metal of a molten playground, scenes of the almost unimaginable devastation that he and his brothers in arms have caused. While the soldier knows that what he sees is all a dream, and that back in the real world he is sleeping in a barracks, safe from the carnage and the bloodshed, he cannot bear the thought of letting go of his wife’s hand, for he is somehow convinced, with that utter certainty that only dreams can endow, that he will never see her again, in this life or the next, and yet, even so, when he hears the distant cries of a bugle call, he shoulders his rifle, kisses her lips and heads back to the fray.

*

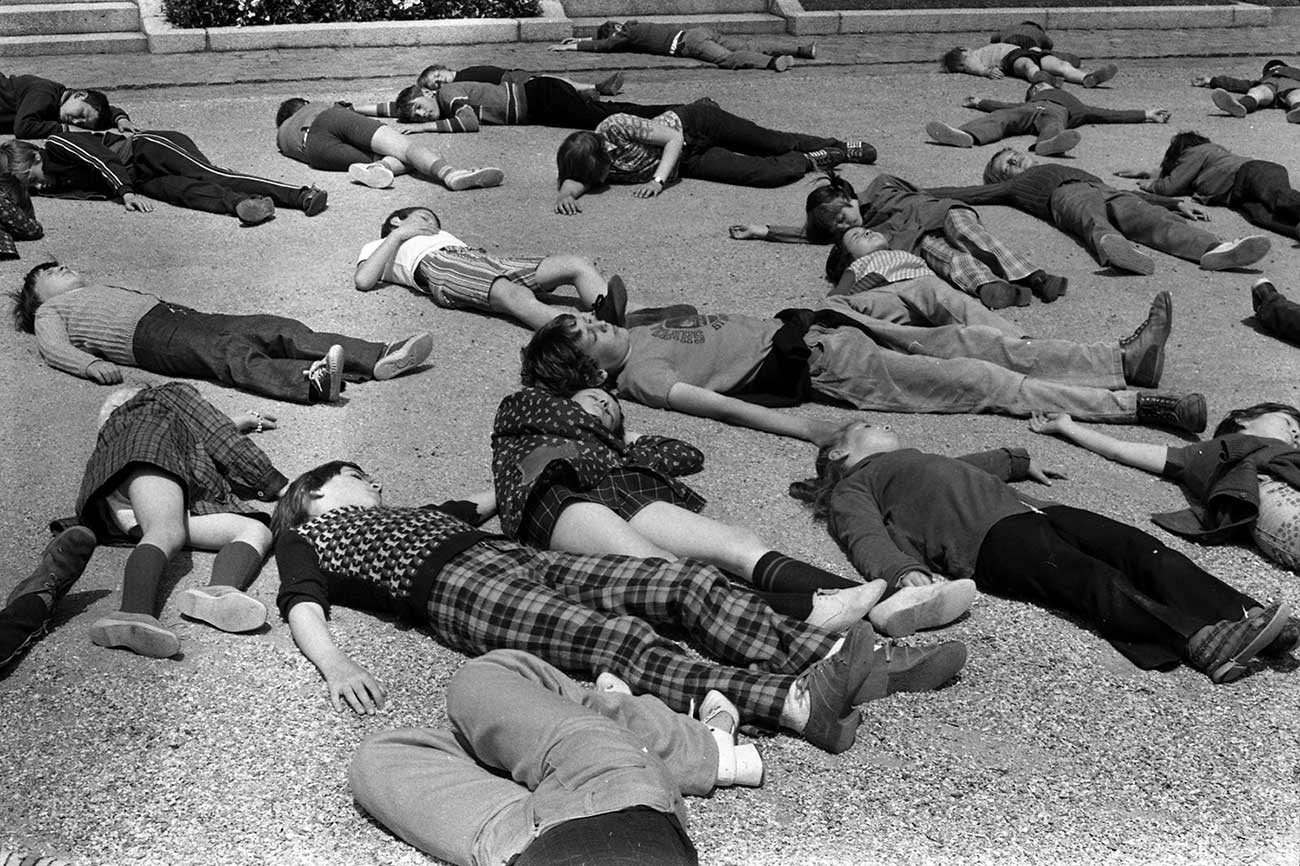

La ville rayée de la carte: on 17 May 1973, all the citizens of the French town of Mazamet lay down on the streets to play dead.

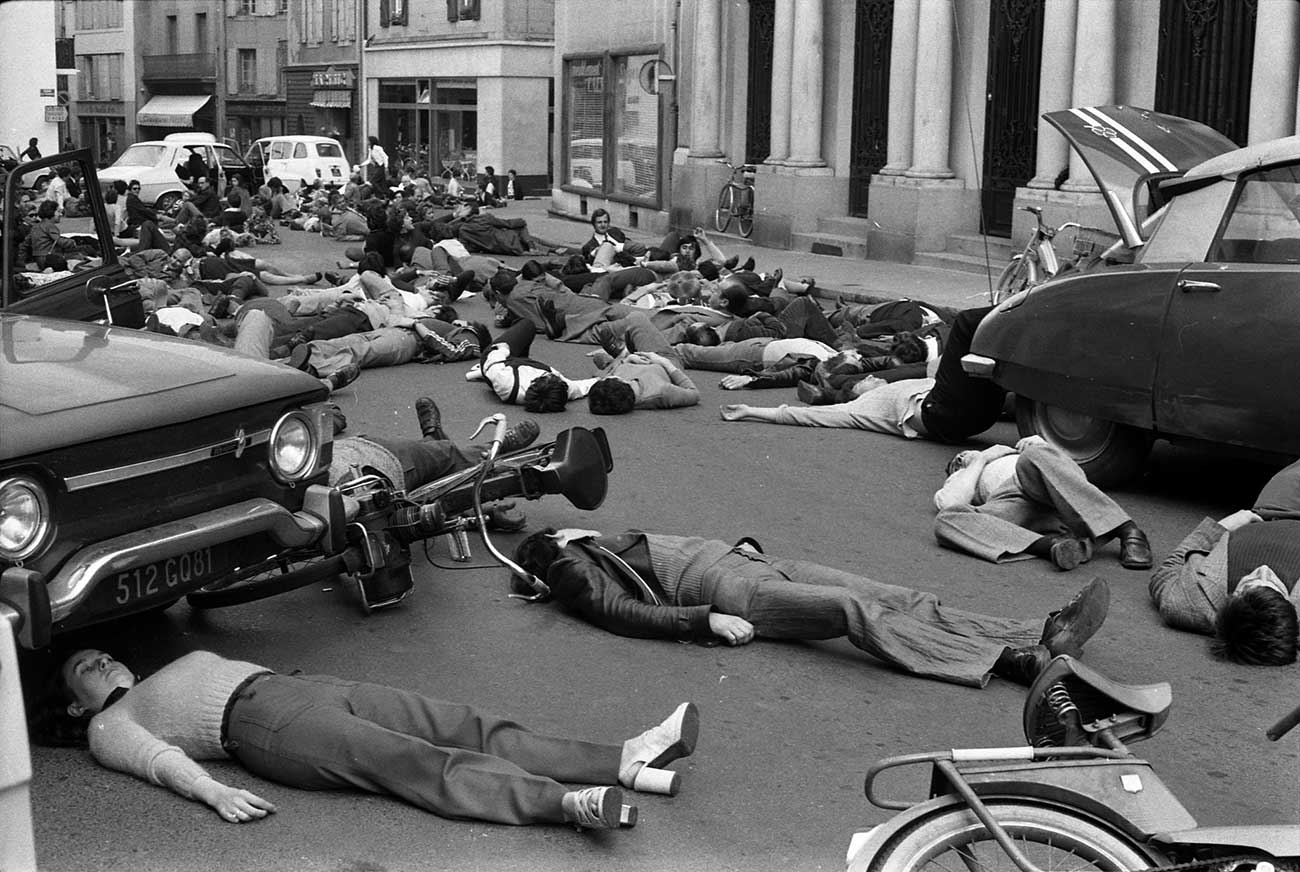

For a quarter of an hour, tens of thousands of men, women and children remained sprawled on the pavement, slumped on sidewalks under the burning sun, or hanging out of the doors of their cars, their arms limp, their legs bent, as if a sudden plague had descended upon the entire town, killing everyone at the same time.

This strange mass performance was not organized by some overly ambitious member of the avant-garde, but by the French road safety authority. Operation Mazamet Ville Morte, as it was named, was meant to draw attention to the dangers of reckless driving. That particular town – a picturesque holiday destination in southern France, cradled between the Black Mountains and the Arnette river and surrounded by dense forests – was chosen because its population mirrored the exact number of people killed in the roads of France during the previous year: 16,610. The whole morbid spectacle was filmed by the Office de Radiodiffusion-Télévision Française and broadcast on the program 24 heures à la Une: the video, shot with several cameras on the ground and a helicopter flying above, shows hundreds of small children prostrate in front of the town’s war memorial, laying on their backs with their faces upturned to the sky, wearing corduroy pants, striped shorts, plaited skirts and ankle high socks, while two blocks away several cars are ablaze. Michel Tauriac, the journalist who had thought up the event, had been convinced right up to the last minute that it would be a total failure (an ex-rugby player and local hero, Lucien Mias, had violently protested the idea saying that ‘A man from Mazamet dies on his feet’), as he seriously doubted that so many people would be willing to drop dead on command, like they were trained animals. But he was wrong: when the day came, even the nuns lay down inside the walls of their cloister.

At two o’clock in the afternoon the Gendarmerie blocked all roads giving access to the city. At 2.15 loud sirens alerted everyone to get in place, while a voice broadcast through loudspeakers set up all over town warned everyone to ‘Be careful, get ready’. At 2.20 all traffic was ordered to halt. At 2.29 the church bells began to ring, and everyone in the city left their homes, their schools, theatres, hospitals, fire stations, post offices, grocery stores, coffee houses, museums, factories, restaurants, workshops, supermarkets and bakeries to cover the streets and sidewalks with their seemingly lifeless bodies. A heavy silence shrouded the whole city, interrupted only by the rapid fire of camera shutters and the whirlwind of the helicopter’s blades. What surprised Michel Tauriac most of all is that people staged their own deaths: unprompted and obeying a strange theatrical impulse, some lay inside their vehicles, peacefully resting their cheeks on the steering wheel, as though they had committed suicide by inhaling the fumes of their exhaust; others hung from rolled down windows, their arms extending to the ground, while several chose to expire violently, thrown over the hoods of their cars by a head-on collision, and lay there, poised like Dionysian statues. Others simply sat down and closed their eyes, their necks propped against the bright chrome of their bumpers.

*

During much of his life, William Burroughs had a recurring dream in which he would wake up in the streets of a necropolis that he came to know as the Land of the Dead.

That dread place, which the author describes in his dream journal My Education (a book that he considered his true autobiography), could be distinguished from his other nighttime reveries by certain repeating signs: he only saw people who were already dead, family members or others who were close to him – Mother, Dad, Mort, the love of his life Brion Gyson, Ian Sommervile, Anthony Balch, Mikey Portman and Joan Vollmer, the wife whom he shot through the head in Mexico City. The whole area, though it felt vast and boundless, always resembled three or four blocks that could be Paris, Tangier, London, New York or St. Louis. ‘And what is outside this dreary claustrophobic area?’ – Burroughs asks: ‘What lies beyond the Expanding Universe? Answer: Nothing. But??? No but. That is all you-I-they can see or experience with their senses, their telescopes, their calculations’. His earliest glimpse of the Land of the Dead is a nightmare vision, its horror compounded by that awful doubling mechanism of the dream-within-a-dream:

Many years ago my first contact with the Land of the Dead: It is in the backyard of 4664 Pershing Avenue. Darkness and patches of oil and smell of oil. In the house now, and I am bending over Mother from in front, eating her back, like a dinosaur. Now Mother comes screaming into the room: ‘I had a terrible dream that you were eating my back.’ I have a long neck that reaches up and over her head. My face in the dream is wooden with horror. It is like a segment of film underexposed. Not enough light. The light is running out. Dinosaurs rise from the tar pits on La Brea Avenue. Oil and coal gas.

The other sign that would let him know, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that he was trapped in the Land of the Dead is that he always faced insurmountable difficulties in finding some place that would serve him breakfast, or any food for that matter.

Burroughs was obsessed with viruses. His books are filled with them. Like the blood of bats, his body of work was a deadly reservoir, a fertile breeding ground for highly toxic thought-forms which sprung from his diseased imagination, mutated and then infested the rest of the world, leaving traces of their antibodies wherever one wishes to look. Steely Dan is not just a rock band, but a gargantuan strap-on, steam-powered dildo wielded by Mary, a young girl who sodomizes her lovers and then snaps their necks. Years before heavy metal was a music genre, it was the name of one of his early characters, Uranian Willy The Heavy Metal Kid, also known as Willy the Rat, since he could feel out threats through two highly sensitive antenna that grew out of his translucent skull. Burroughs famously claimed (with that awful prescience that makes him indispensable) that the word itself is a virus. It is not a human creation but something alien to our species, an entity that infected early man and has been using us as hosts to propagate and make copies of itself. It resides within us, it controls and forms us. We do its bidding, unwittingly. That which we feel as most human – the constant voice inside our heads – is really an Other living inside us in stable symbiosis, a foreign invader that forces us to speak continuously, even if only to ourselves: ‘Modern man has lost the option of silence. Try halting sub-vocal speech. Try to achieve ten seconds of inner silence. You will encounter a resisting organism that forces you to talk. That organism is the word’. Ebola, flu, smallpox, herpes, hepatitis and mad cow disease figure prominently in his writings, alongside many other imaginary pathogens: The Doomsday bug, a radioactive virus, smells of shit and metal and causes young men to collapse into fits of sadistic frenzy; the B-23 virus, a sexually transmitted infection that presaged the HIV/Aids epidemic, its only treatment massive doses of opium; there are viruses which cause bouts of compulsive masturbation so extreme as to lead to death, others stain people faces and crotches a furious red and drive young men to ritual murder; some of his viruses are duds, malevolent codes that fail to achieve their biological destiny, ‘fated to languish unconsummate in the guts of a tick or a jungle mosquito, or the saliva of a dying jackal slobbering silver under the desert moon’, while others cause hallucinatory spells which feel not just lifelike but vastly superior to our dull waking experiences. But of all his viral creations, the ‘word virus’ is particularly strange, as he includes among its symptoms not only those that one would normally attribute to a disease of this kind (coughing, fever, shortness of breath, inflammation) but also ‘the production of objective reality’. The word virus, Burroughs wrote, fixes meaning. It pins reality down in our minds as the entomologist does with the specimens of his collection, skewering their insect bodies with thin metal rods. ‘Viruses make themselves real’ – Burroughs said, ‘It’s a way viruses have.’ Fascinated by death as he so clearly was, viral organisms held a special power over him, for they occupy a strange, liminal space between the realms of the living and the dead: ‘It is thought that the virus is a degeneration from more complex life-forms. It may at the time have been capable of independent life. Now has fallen to the borderline between living and dead matter. It can exhibit living qualities only in a host, by using the life of another – the renunciation of life itself, a falling towards inorganic, inflexible machine, towards dead matter.’ He also thought that every species has a Master Virus, which is a deteriorated image of that species, and once wrote that we humans ourselves may well be a type of virus, with no purpose beyond endless replication, ‘one that can now be isolated and treated’.

*

The Covid-19 pandemic is ravaging cities across the world, but up here in the mountains little has changed.

I am writing this during the last days of May, in a remote town in the south of Chile. Across the country, millions of people are in lockdown, quarantined or self-isolating in their homes, surviving, as it were, at the edge of life, which is exactly how the professor of microbiology, E. Rybicki, described the peculiar territory that viruses have claimed for themselves. Here in the southern hemisphere, May is the month when the last flowers wilt and the fiery colors of autumn carpet the ground. For wild animals, food becomes scarce; in Santiago, pumas now roam the streets.

They have come down from the Andes attracted by the eerie silence that has fallen over the capital during the nation-wide curfew. These sleek phantoms, that no Chilean is truly familiar with, as they are shy and elusive beasts that avoid humans at all costs, are being filmed as they strut along posh neighbourhoods by people who have never seen a predator up close in their lives. Here in my own garden, a charm of hummingbirds fights over the last drops of nectar. One of them ferociously guards the feeder I have hung among the many creepers and vines which I stubbornly try to grow, year in and year out, in spite of the fact that the winter frosts kill most of their new shoots. I have never seen hummingbirds in such numbers. I used to have to lie still in wait for a very long time before one of these emerald creatures would appear, now they almost bump into me as they dive around, blinded as they are by rage and thirst. Their bickering is a spectacle which I can’t help but enjoy, although I’m aware that it is a sign of just how cruel the drought here in Chile has become, for the wild flowers and blossoms they depend on are now few and far between. Theirs is a hectic life of constant hunger, miniscule hearts racing at a thousand beats per minute. To us, they are enthralling wisps of beauty gone in the blink of an eye, delicate as the flowers on which they gorge; to them we are slow as trees and drab as brown clay. Violence is the one thing we share: their beaks, needle sharp, are constantly clashing over food meant for much smaller things. A hummingbird must eat incessantly or die. Like us, they rest at night, falling into torpor, a state of suspended animation during which their body temperature drops below hypothermia, their breathing stops almost completely and their heartbeats slow to a crawl. Fluffed in a nest or hanging upside down, their sleep is death-like, deeper than anything we could ever imagine, filled with nectar dreams. Although they weigh less than three grams, they can withstand levels of turbulence that would rip a fighter jet apart, and yet they are far from perfect grace and die in many ways. It takes only a couple of hours with no food for them to starve. Some don’t survive the cold of night, are clawed by cats or break their tiny skulls by crashing against our windows. Others die writhing in pain after being stung by angry wasps or swarms of covetous bees. Agriculture and urban expansion destroy their habitats, pesticides and toxic mold poison their blood, but even in death they retain much of their beauty, as if it were a final gift to us from this sun-kissed bird: their diminutive corpses, if left in light, will remain perfectly preserved, for their every tissue is drenched in sugar.

There are less than fifty of us here in town. The nearest city is an hour’s drive away. I haven’t seen another soul in months. My wife is the one who goes down the mountain road every ten days or so to buy food and provisions. When she does, she takes our only working phone in case of an accident, and my daughter and I are cut off from the rest of the world. If anything happened to her, I would be the last to know. In the conditions that we are in – with the country paralyzed by the pandemic scare and thousands of new cases reported each day – anything that might happen spells tragedy. Today, for example, my dog dug up a dead rat.

She found it in the garden a week ago, while it was still agonizing. It had probably nibbled on one of the little poison baits that I set up in the attic. My dog brought it to me and laid it at my feet; their scuttling and scratching had been driving her half mad, and she was clearly proud of herself for finally having caught one. I shooed her away, afraid of the deadly chemicals still coursing through the vermin’s bloodstream, and buried it some distance from our house. But I did not dig deep enough. This afternoon, my eight-year-old daughter came screaming into the house: ‘The rat, the rat! Kali dug up the rat!’ I rushed outside and stood there, staring down into the hole, with my dog waging her tail beside me, snout and paws blackened by mud. I tried to calm my daughter down. Of course she didn’t eat it, it was far too large, she probably just toyed with it for a while, or buried it somewhere else. We looked around, but since we couldn’t find it, I called the vet. I spoke to her at length, and then reassured my daughter that everything would be fine. But I cannot be sure. The symptoms of that particular poison take several days to manifest, and they are gruesome. Bruising, vomiting, loss of appetite and equilibrium, bleeding from the eyes, nose, ears and mouth. There is no specific antidote and no treatment. The only thing that we can do – the only thing that all of us can do – is watch and wait.

Hope for the best.

Benjamín Labatut’s When We Cease to Understand the World, translated by Adrian Nathan West, is forthcoming from Pushkin Press.

Photographs © André Cros