Kaitlin Maxwell is daughter and granddaughter to the two women in this series. Maxwell appears with them in some pictures, imitating or mimicking their poses, wearing the same costumes. She shoots them alone, shoots herself alone, she poses them against different backgrounds, mostly domestic spaces, but not only. Maxwell’s images represent an intense curiosity about them, the women who raised her, about who they are, apart from her, and who she is because of them. Maxwell wants to know if she looks like them.

Nine and six years younger than my two sisters, I watched them as I grew up. They fascinated me. From my bed, I watched my middle sister put on her bra on a freezing winter morning, and felt sorry for her – I wore an undershirt, but a bra wouldn’t keep her warm. They were my brilliant sisters, my heroes, until they were not.

My mother, the first female, was a ‘prude’. Our female bodies were not talked about, they were our secrets; what happened to them, and what we did with them, was secret. We didn’t walk around naked. My father’s body was also kept under wraps. When my breasts started growing, I thought the small mounds, or lumps, might be a disease.

Maxwell’s images are revelatory to me, unusual: she looks at her close female relatives as characters in their bodies, with bodies. Daughter and granddaughter, she seeks ways of seeing them, and to perceive femininity, sensuality, sexuality and ‘sexiness’ in them and her, and also as coded images. That is, she depicts all of this as ‘just pictures’ of women. Her mother and grandmother are shown as sensual, voluptuous, while the archetypical ‘Mother’ is not. Good-looking, fit women, they pose, and don’t; they reveal their bodies, and don’t.

The poses and postures of ‘femininity’ and ‘womanhood’ supply part of Maxwell’s material. Simone de Beauvoir famously wrote, women aren’t born, they are made. (I love Aretha, but don’t believe there’s a ‘natural-born woman’.) And, the concept of ‘natural’ changes over time, indicating that so-called ‘natural behaviors’ also change, or that nothing is natural. Females will be inculcated, educated, indoctrinated with how to look; how to get looked at; how to behave, and what they can expect of life ‘as women’.

In photography, the knowledge that pictures are constructed, that they are in some sense always fictional – that is, made up – has troubled and wounded the medium. A photograph can’t assert itself as a fact or document. Because like the humans who invented the medium, photographs can dissemble and shape-shift. It is this understanding among photographers that presents a great dilemma: they assemble or frame or construct an image that already is an image, and already seen.

When I was seven, I saw Marilyn Monroe in the movie Niagara. I don’t know who took me. In one scene, Marilyn appeared in a tight-fitting, low-cut fuchsia dress. I had never seen anyone like her. She was sexy. I sent away to her Hollywood studio for an autographed picture. It was the only time I ever did that. It was a little black-and-white picture of her in a bathing suit. She was smiling, posed high on her toes, standing in profile, and looked cute and friendly, I thought.

Monroe became an object of fascination to me, a baby feminist. Her performance of sexuality startled me. Was I supposed to be like that or only admire images of women like that. In the early 1980s, I tried to write her autobiography, to write as Marilyn Monroe, tell her story intimately, but after reading what had been published about her, I became too depressed to write it – her early life was miserable – and, in the 1990s I turned what I had written into ‘Dead Talk’, a short story about Marilyn.

Animals flirt, give off signals for mating; male birds do elaborate dances, their colors brighten and shimmer; some males fight to the death for a female, and sometimes an animal merely rubs against a tree or sprays leaves to lay down its scent. Marilyn Monroe’s flamboyant dress, her exaggerated stroll, her ass in perpetual movement modeled one version of the female of my species using vivid, revealing costumes to catch a mate.

In this Western world, it’s a toss-up. Sometimes it’s the job of females to attract partners; perfume can be used as scent. Men often appear not to need prompts; they were bred to play the aggressor. (They have image problems, also.) Too passive, they may not get what they want. Too aggressive, they might frighten their target. Some are predatory.

In several of her photographs, Maxwell’s women strike poses that might be considered sexy or provocative. These replications are studies in sexiness.

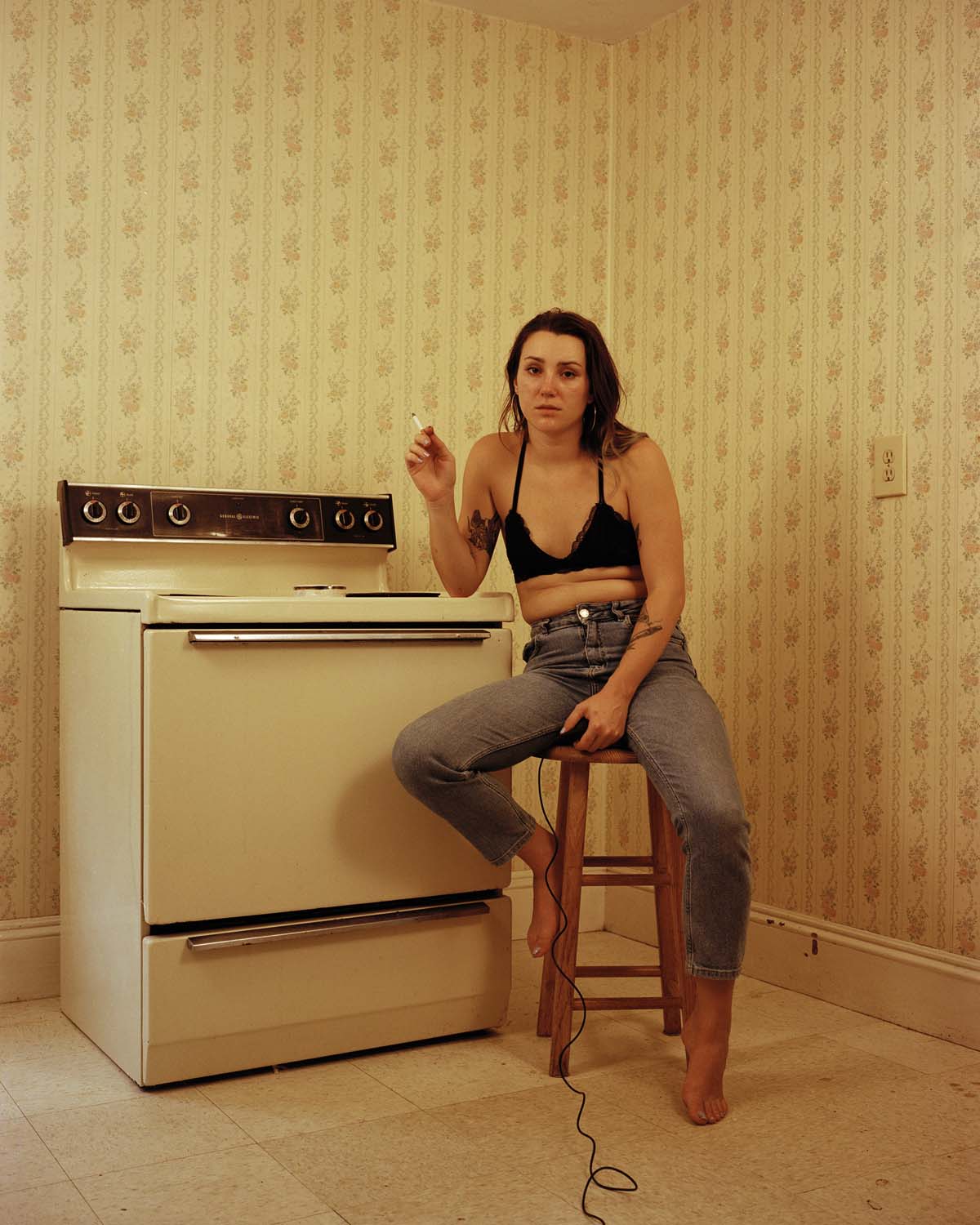

In the first image of the series, Maxwell faces the camera, its remote device on her lap, and shoots from there. She is sitting on a stool in jeans and a black bra, beside a yellow stove. Her legs open into a V and mimic the V of the corner behind her back. The kitchen’s yellow wallpaper, the background, denotes its era, the 1950s or 1960s.

(My immediate association to seeing the yellow wallpaper was a story, ‘The Yellow Wallpaper’, by Charlotte Perkins Gilman in 1892. A woman is suffering a terrible, post-partum depression, and kept in a room – a cage, a prison – with yellow wallpaper.)

Maxwell shows herself in a homely, dated environment. The photographer makes herself a target, boldly central in the frame. She is also to be investigated. Later, as the series progresses, Maxwell will contrast this homeliness to her mother’s and grandmother’s versions of domesticity and the feminine.

Voluptuous bodies wear casual or revealing clothes. The women appear not to mind being shot; Maxwell herself seems more tense or, as the photographer, less comfortable in front of the camera. Maybe the women were uncomfortable, they just know how to perform. A viewer can’t tell. Poses are performances, and Maxwell’s photographs are not didactic, yet one could decide that, through her photographs, she is depicting a girl’s education of learned ‘womanliness’, and how to do it. ‘Strike a pose.’

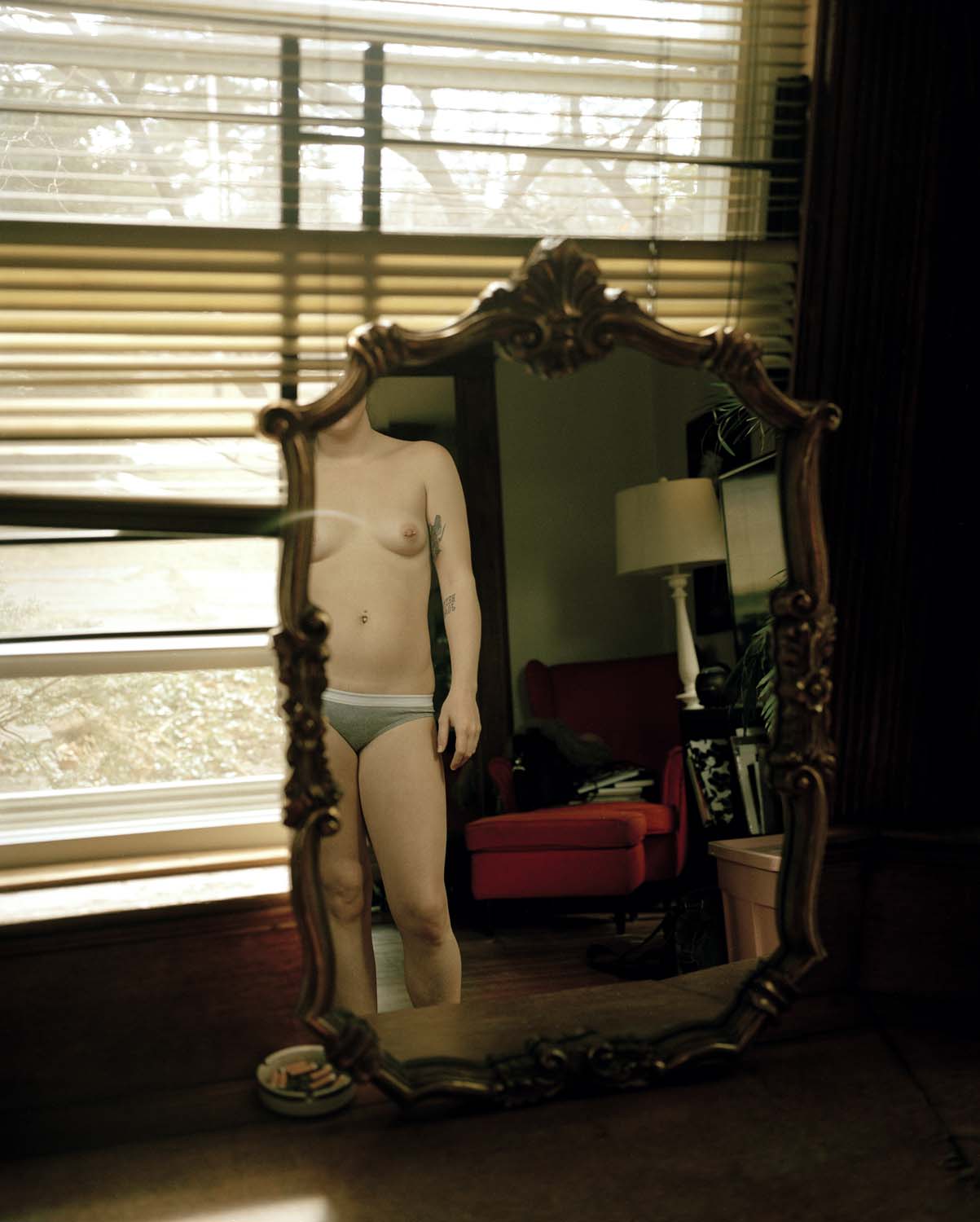

She uses bright light, natural light, shadow or low light to build moods, feelings – openness, secrecy, obscurity, ambiguity. She mostly foregrounds her subjects, while the background embraces them – the women appear to have a place, in a place. But Maxwell frames her subjects as if an actual border were surrounding them.

She uses color subtly, often pastels.

Her pictures mostly work with a few elements, and not extraneous information. There’s overhead light in a bathroom scene, where her grandmother applies lipstick. Maxwell has shot her from an angle. We see her in profile, and also, her full face in a mirror, one side of which is bright, the other dim. The mirror she looks into is divided.

In Maxwell’s images, women mirror each other. Maxwell lies in bed, part of her body under covers, while her grandmother lies, curled on the floor in a shift dress. In two other shots, similar poses are struck by Maxwell with her mother, and with her grandmother.

In the first, Maxwell and her mother stand side by side in a backyard, an old wood fence behind them. The mother’s head leans toward her daughter’s, and both are wearing black pants, casual tops. They look at the camera, they look ‘ordinary’.

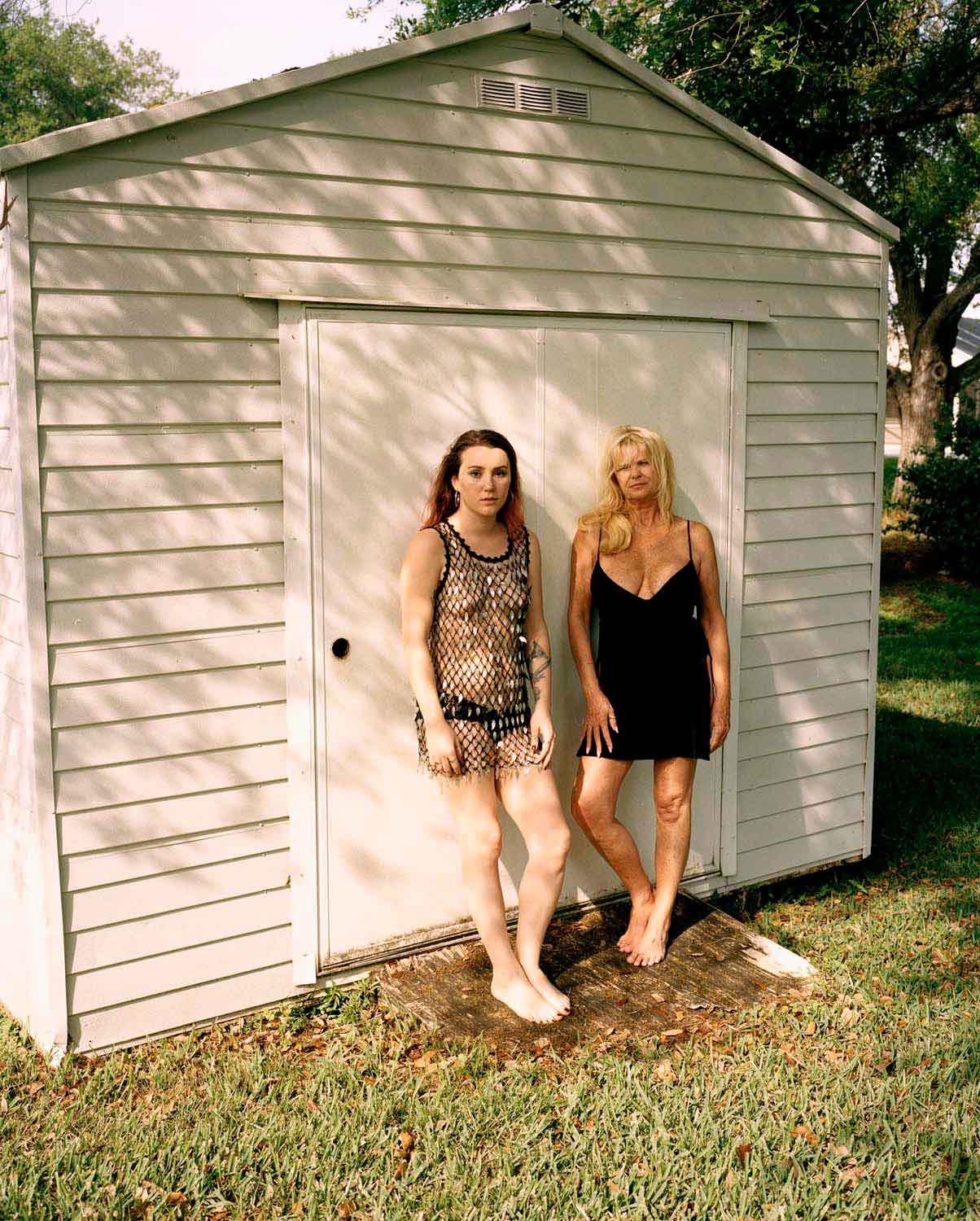

In the other, Maxwell and her grandmother stand in front of a white garage door, next to each other but not touching. Her grandmother is wearing a low-cut black sleeveless dress that reveals her large breasts. Maxwell wears a see-through top, her smaller breasts peeking through the interstices of the netting. Both women have angled their legs, as models do to present a slimmer image.

Dueling images, let’s say, juxtapositions within juxtapositions, facing each other.

Apart from her formal concerns, Maxwell’s content – femininity, gender, sexuality, women as constructions, representations and self-representation, mothers, daughters – are compound(ed) subjects, not separable in her pictures. To represent females and their bodies is a thorny job. Any one issue engages others. ‘Motherhood’ is a construction, and its representations of maternity shape ideas about how a mother should look and act. A mother is also an image – but whose.

Women look at women, men look at women, straight, queer, non-binary individuals look at women – looking is complex.

I’m recalling Laura Mulvey’s seminal essay on classic cinema’s ‘look’ and ‘gaze’ at women, a function of patriarchy, control by men of women, particularly in a narrative, which breeds in women an internalized male gaze. (Recently, Mulvey has said she understands her seminal essay as a manifesto, as polemical.)

A woman is looking at other women, she gazes at them, and herself, she makes pictures of all. Viewers look through her lens, her eye. So, as a viewer, I can only project, which is what I am doing. My responses or interpretations, my seeing, get filtered through my psychology, my associations. My curiosity stems from a desire to apprehend the psychological moment in them, and how and why Maxwell’s work produces or promotes certain stories.

I don’t know if I can see, separate from my gender, the ideas I have unconsciously absorbed. I don’t think I’m a woman. Consciousness awakens one to inherited or educated biases. That is my hope. I might be able to see as a queer woman or straight man, say. Or, I might be caged in my own room of yellow wallpaper. I can’t claim a clean sweep of that room’s indoctrinations, my early education, can’t say it’s been done thoroughly or completely. Making formal analyses helps me, I think, see other ways than subjectively to see, but still . . .

I suppose I want to find a coherent narrative, and know I will not. Questions have been around for a long while: if female bodies are represented by women, are they any different from those shot or painted by men? Maxwell’s photographs dive into these muddy waters in visual monologues and dialogues.

Photography’s virtue is its vice: a seeming, immediate clarity – what you see is what you get – hides its truer illegibility.

One day, while writing this, I turned on the radio for background noise, which fills in for something, maybe an absence of ideas. It’s a woman’s voice. ‘My husband thinks I’m obsessed with my breasts.’ She’s written a book about women’s breasts, the American obsession with breasts since the Second World War. I can guess what she’s going to say, and turn off the radio to wrestle with how to write about breasts in Maxwell’s pictures; they figure prominently, under clothes or partly unclothed. I might be looking at their breasts the way a man would.

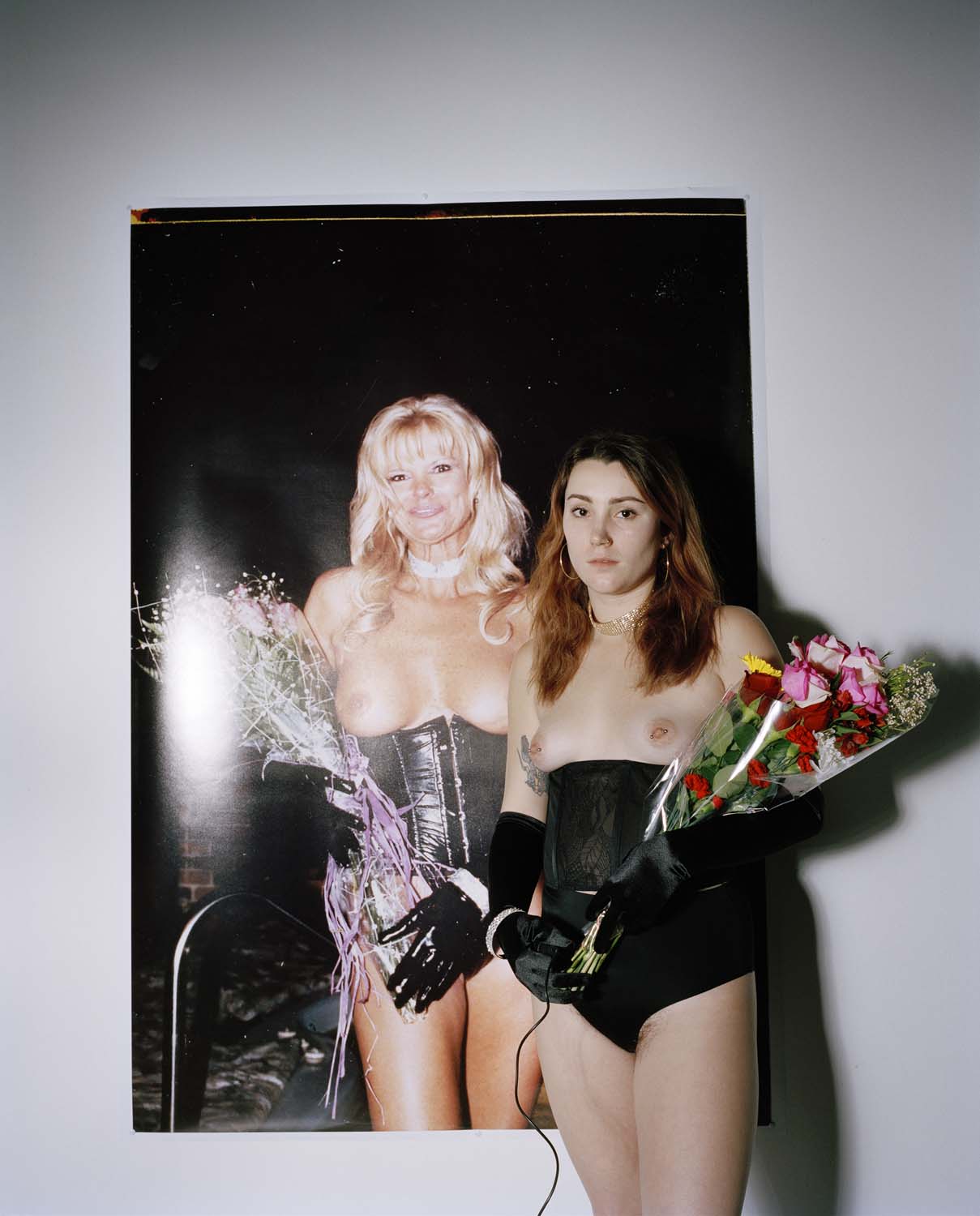

Maxwell seems to be comparing and contrasting her body and their bodies. In one photograph, she wears the same costume as her grandmother. Their breasts are exposed in the same way, just above the midriff of their lingerie.

The first time my mother mentioned breasts to me, I was five and with her at a beach club my family had joined. An elderly woman in a bathing suit passed by; she had extremely large breasts that hung down almost to her waist. My mother, who was not ‘busty’, said: ‘It’s good to have small breasts so that doesn’t happen when you’re old. And then your back won’t hurt.’ She never said anything like that again.

Toward the end of the series, Maxwell presents two suggestive, ambiguous and puzzling works, disconcerting in ways her other photographs or scenes are not, and they are of herself – self-portraits. She is sitting at the edge of a bed, fairly close up, and wearing a red plaid shirt. Blood is dripping from her nose; a hand is raised almost shoulder level, one finger also bloody. Her face seems naked, surprised, upset, shocked. She appears to have been crying.

It took me a while to recognize her bloody nose. (I think it is a bloody nose, I have had bloody noses.) This pose, and why she is showing us it, suggests many responses, and I find myself associating wildly. First, blood and women, menstruation and other bodily functions. But the blood forms a straight line from her nose down to her chin, then across her upper lip, forming a cross; the way she is holding her hand up and cupped, with two fingers raised more than the others – this, I think, mines religious imagery. Stigmata, stigma, a sign of disgrace.

The photograph’s ambiguity allows, encourages, sensitive or harsh readings – for one, women’s shame about their bodies. Not all women, not in all societies, not all at all. This shame is mostly a hidden terrain, and contemporary women are supposed to be over it. If only.

A woman can feel shame about her vagina. Vagina dentata! She might be embarrassed about having her period, or the ‘curse’. (My mother never used that term; she also never told me about periods, I sent away for pamphlets.) Come menopause, this woman will be told she’s no longer attractive, here’s room on the shelf. Controlling weight, that fixation to be skinny, functions as a way to submerge these other feelings, to control the body. It’s an illusion, but an all too common one. Her body is trouble. The stigma is to be a woman.

Maxwell has set her final scene – a self-portrait – in a pink bathroom, with pink tiles, in soft pink light, pink towels on a rack. The background is in soft focus. Maxwell wears a delicate pink bra and pink half-slip, and is seated on top of a toilet seat. Her hair is pulled up neatly in a bun; she is looking at the camera at an angle, not facing it, the remote again in her lap.

Maxwell’s look at the camera, at the viewer, seems significant, and different from the other self-portraits. She might be peeking at us, exposing herself. Setting it in a bathroom, she has invaded a private realm. The photograph acknowledges she is doing this, exposing herself and her mother and grandmother. Maxwell has taken liberties, and recognises that she is invading their privacy with her pictures of intimate relationships. She also reminds viewers of their/our common bodily functions.

This picture is beautiful, I think, though its setting might read as unglamorous. It’s a compelling picture, for one, because of Maxwell’s gaze, a question rests in it, and also defiance, and yet a sense of serenity. Maybe a feeling of completion for her.

This final picture cannily returns us to the beginning, to her first photograph, another self-portrait. Maxwell is in a kitchen, sitting next to a yellow stove. She starts the sequence with yellow and ends it with pink. It’s a soft landing.