Franz Kafka is well-known for his novels The Trial and The Castle, writing famously preserved by his friend and collaborator Max Brod, against the author’s wishes.

Kafka’s friend Max Brod collected and preserved not only his literary manuscripts but also his drawings, beginning as soon as Kafka had completed them.

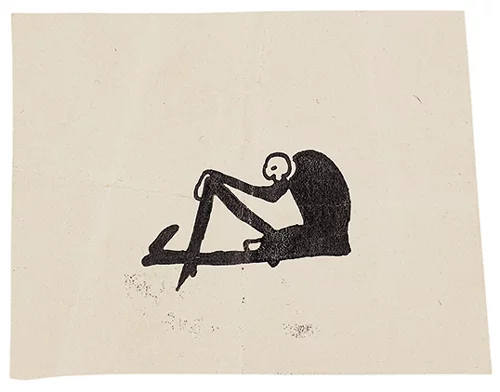

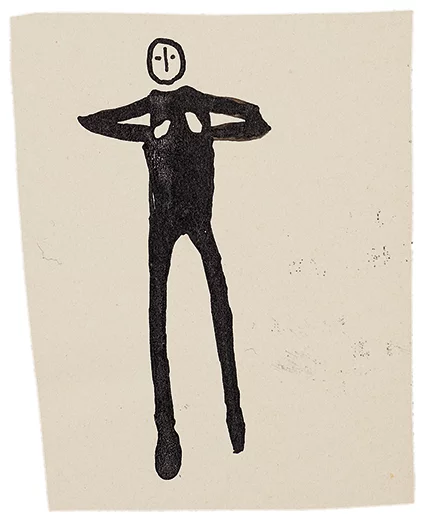

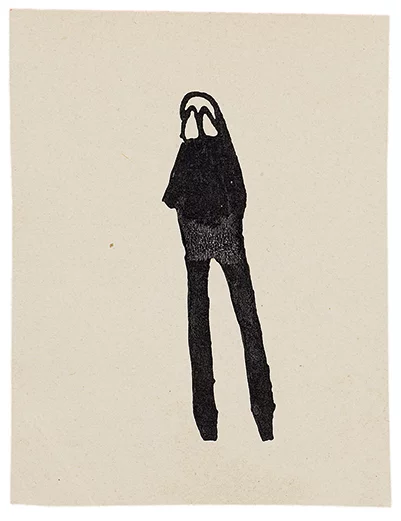

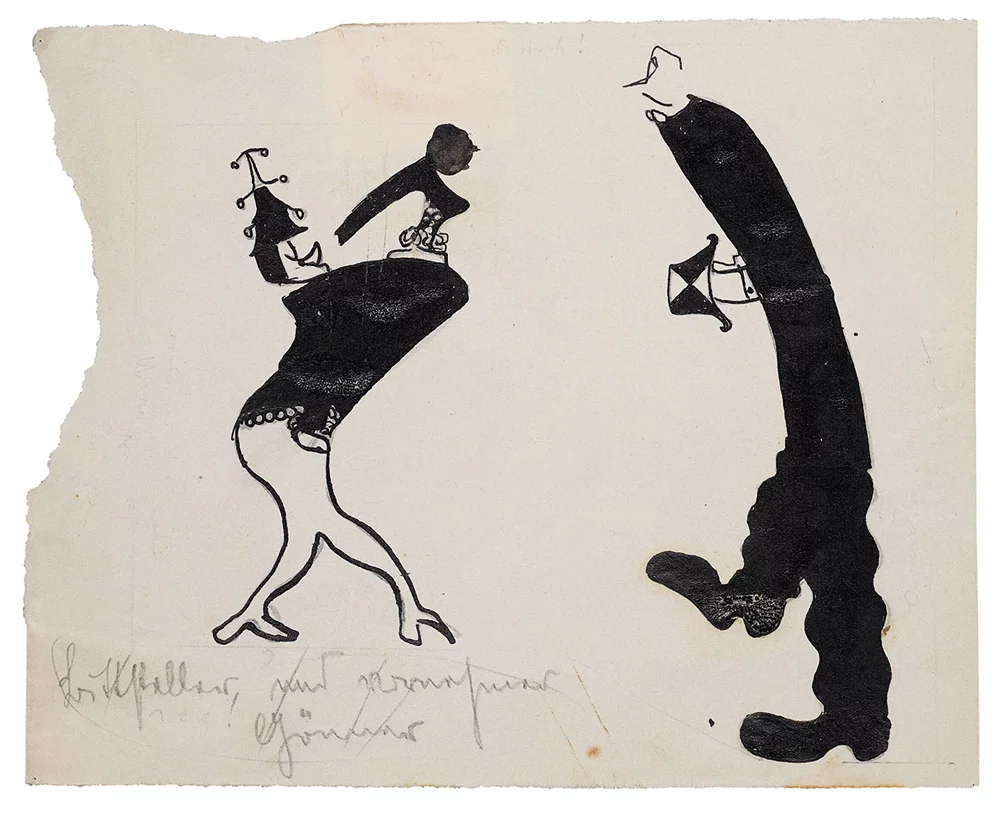

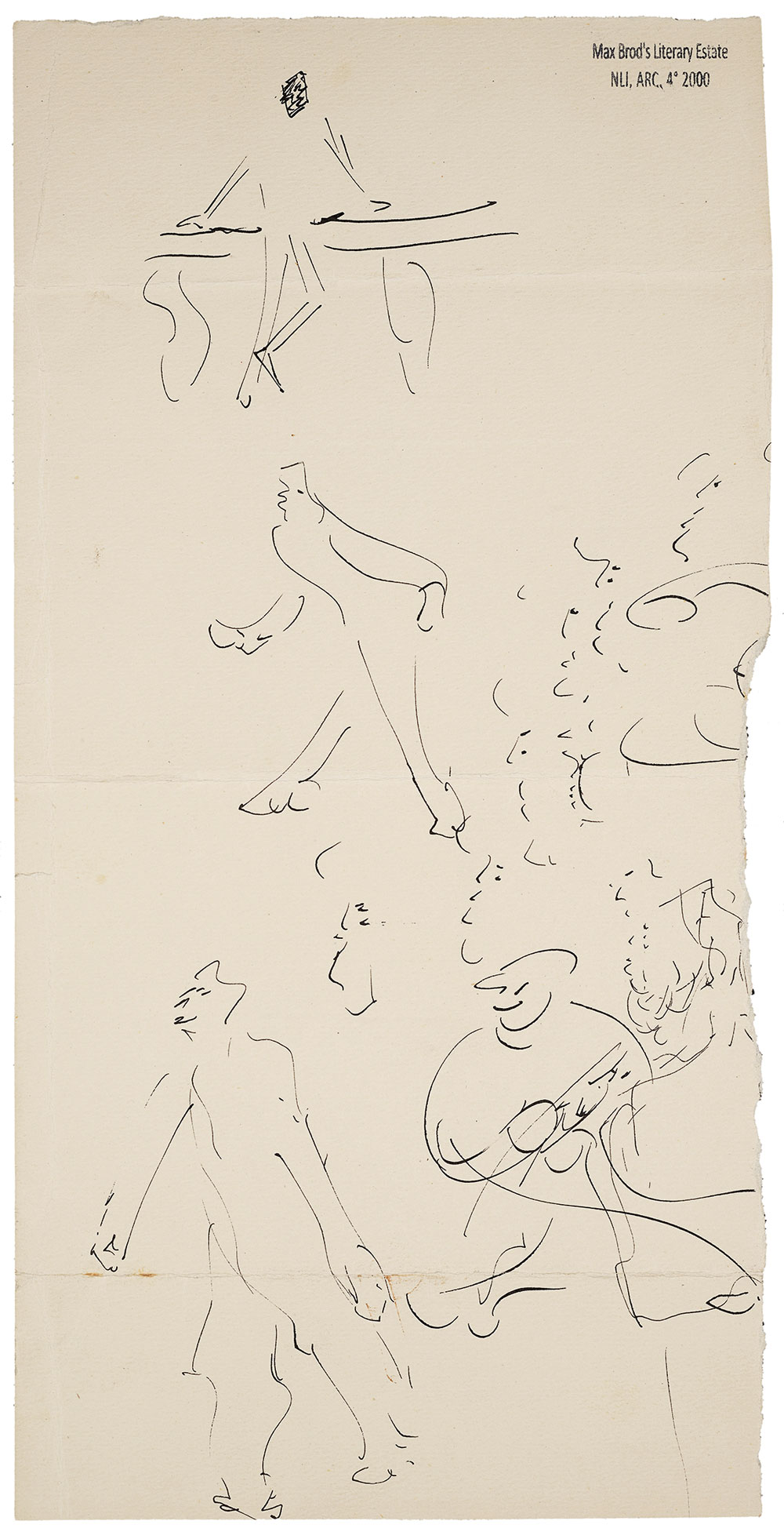

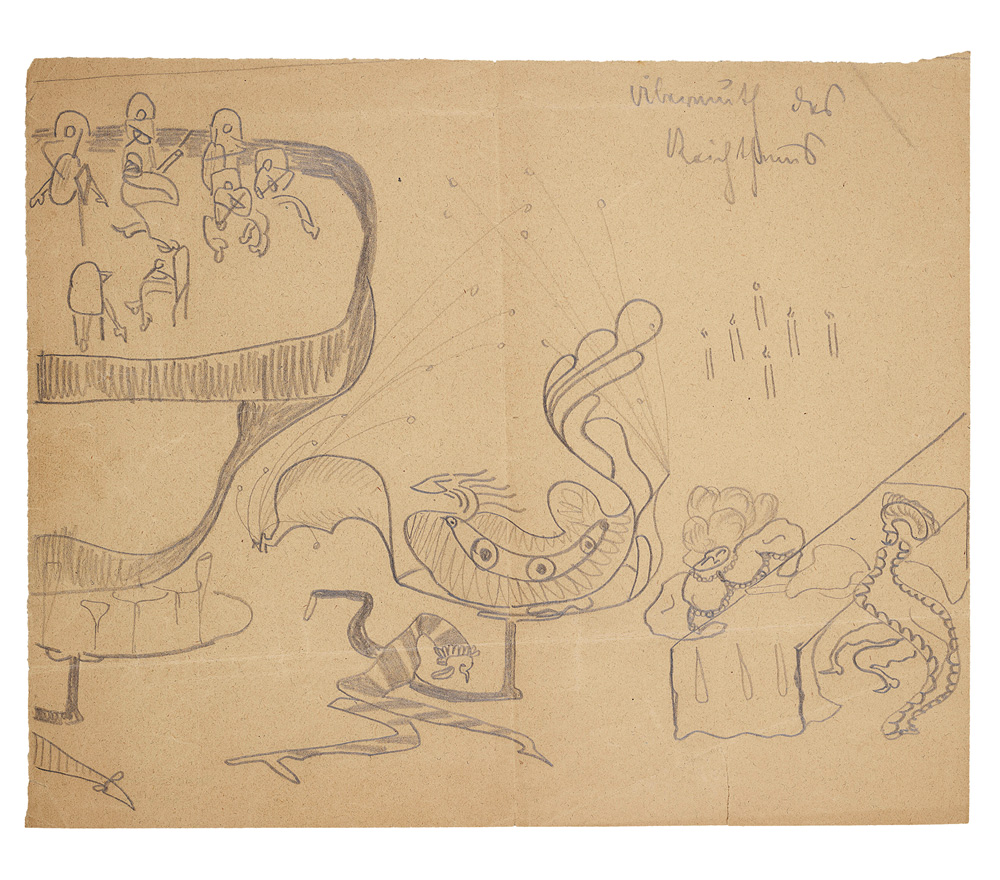

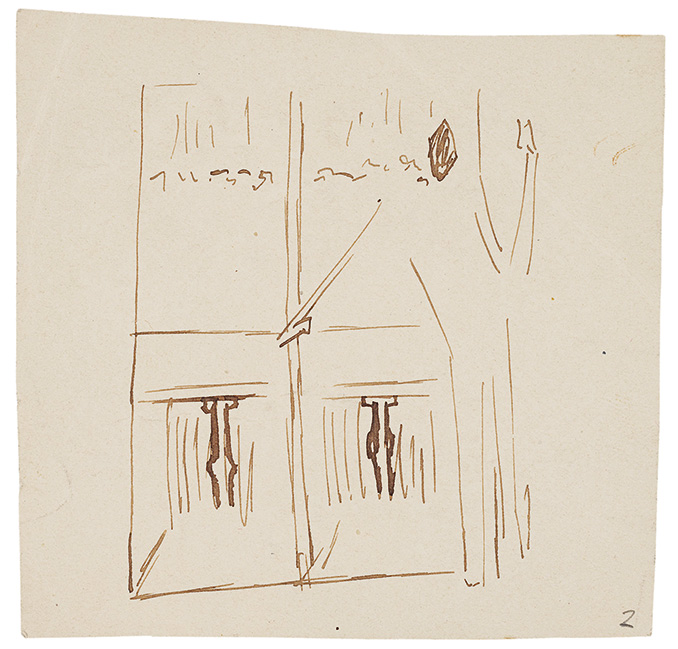

Particularly from 1901 to 1906 – his years as a student at Prague’s German University, during which time he was also making his first attempts as a literary writer – Kafka practiced drawing, took drawing classes, attended art history lectures, and sought to establish a connection to Prague’s artistic circles.

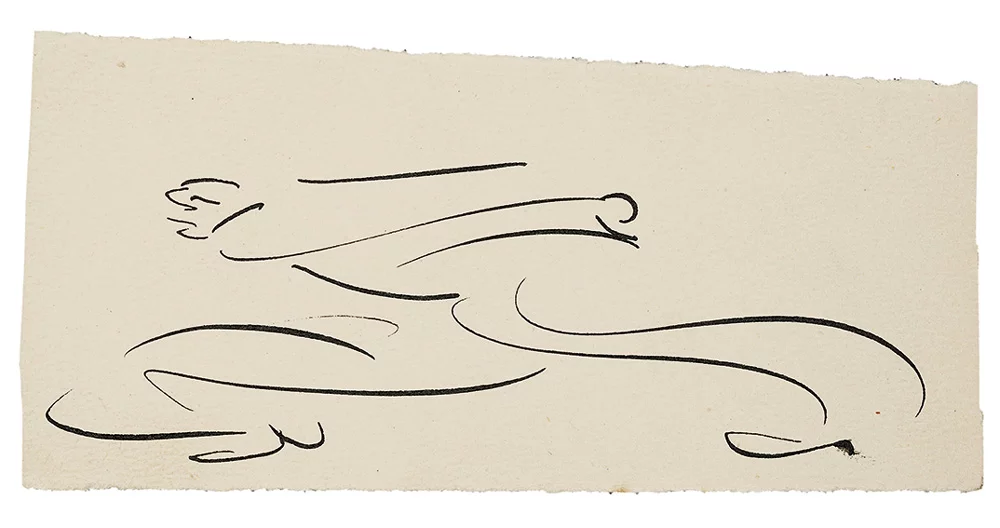

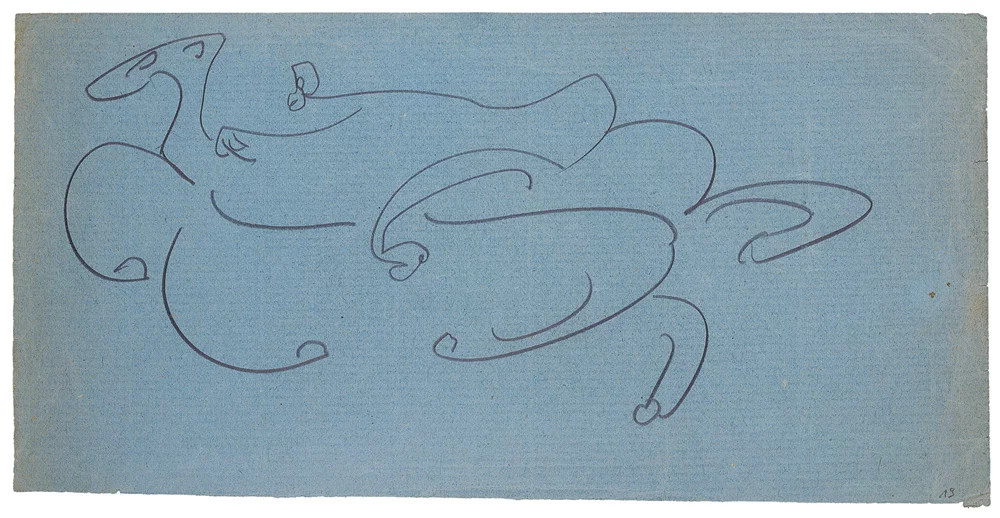

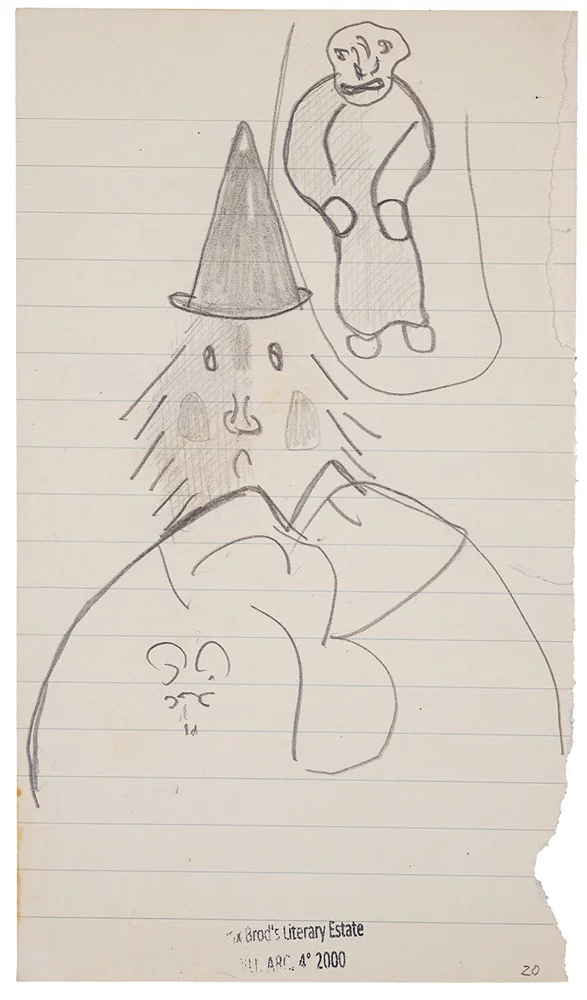

Kafka’s drawings, which he executed with evidently serious intent, did not seem to him to merit preservation; however, they held great appeal for Brod, who was pursuing his own artistic ambitions around 1900, trying his hand at drawing while also supporting contemporary artists and selectively collecting their works.

Brod preserved his own artworks and the works he collected, as well as Kafka’s drawings, for the rest of his life. In an appendix to his book Franz Kafkas Glauben und Lehre (Franz Kafka’s faith and teaching, 1948), Brod writes: ‘He [Kafka] was even more indifferent, or perhaps better, more hostile to his drawings than he was to his literary production. Anything that I didn’t rescue was destroyed. I had him give me his ‘scribblings,’ or I rescued them from the wastebasket – indeed, I cut a number of them from the margins of the course notes from his legal studies.’

In spite of this disregard, Kafka found his own drawings important enough to merit specific mention when describing his estate in his will and testament of 1921. There he referred not only to his ‘writings,’ but also to his ‘drawings,’ albeit requesting that both be destroyed:

Dearest Max, my final request: whatever diaries, manuscripts, letters from myself or others, drawings, etc. you find among the things I leave behind (i.e., my book cabinet, linen cupboard, desk at home or at the office, or wherever else you might come across them), please burn every bit of it without reading it, and do the same with any writings or drawings that you have, or that you can obtain from others, whom you should ask on my behalf. . . . Yours Franz Kafka.6 [Emphasis mine.]

As Kafka could well have expected, Brod declined to carry out this ‘herostratic’ act – and with good reason. Instead, he preserved the drawings as well as the writings as conscientiously as possible.