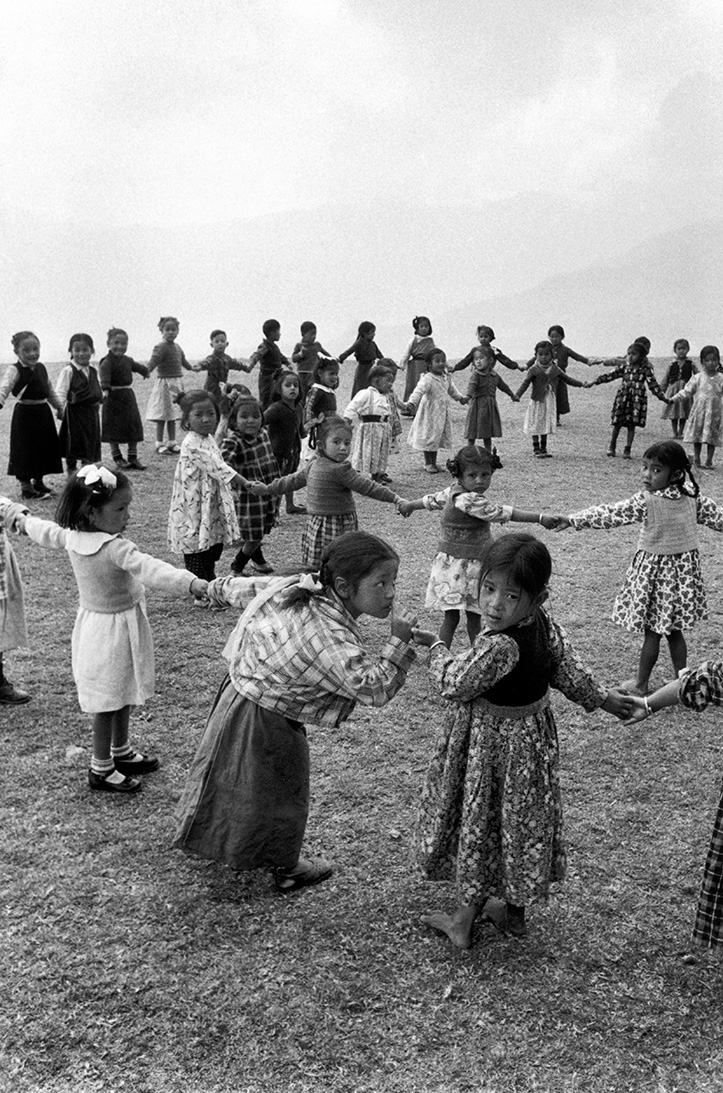

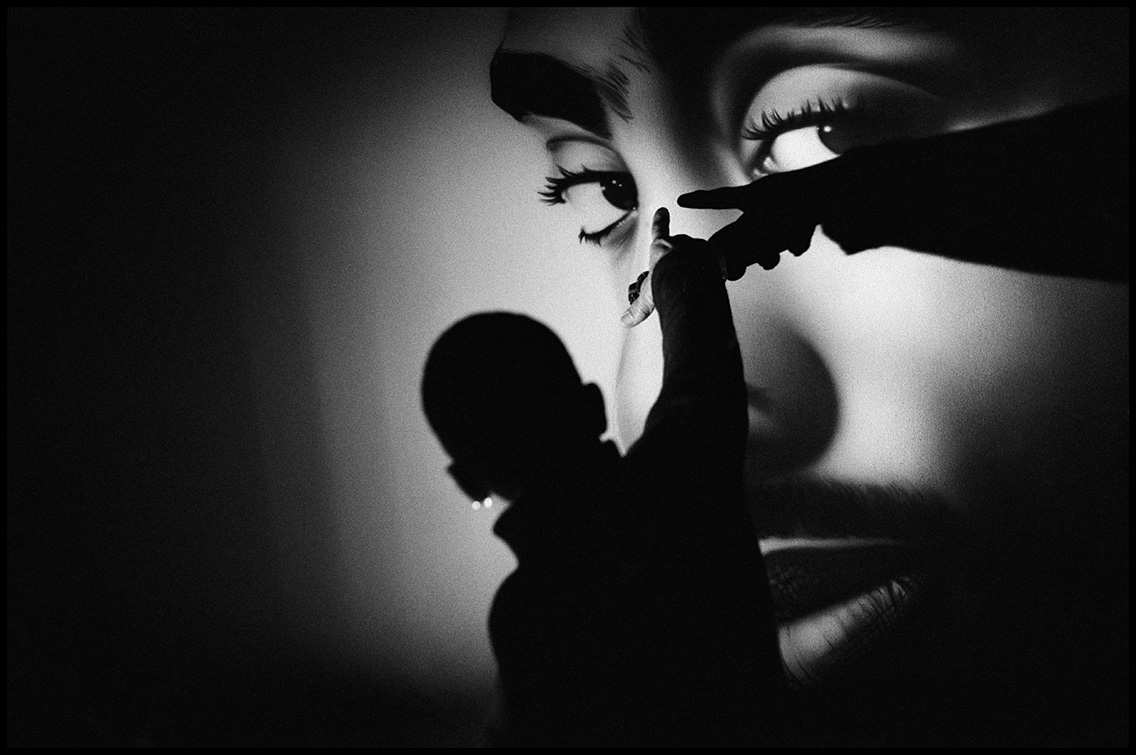

We are all very small, standing together in the hall, and a teacher tells us not to hold hands, not to huddle up, but to step away from each other, to spread our arms as far as they will reach and swing them back and forth and clear a horizontal, arm’s-length circle of space around our bodies. On the first day of school, here is a new unit of measurement that can also be used as a weapon, if applied correctly, like a rock in a sock – our arms the socks, our fists the rocks.

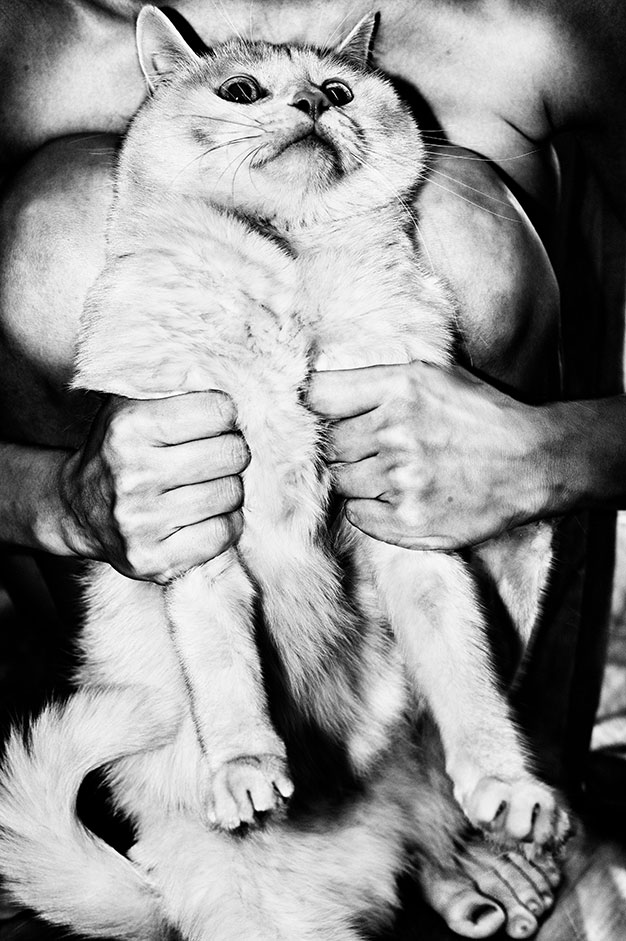

There is always a cat sitting on the kitchen windowsill, in the background of every ordinary and extraordinary event, a softly focused silhouette, a pair of piercing eyes. I am away at university, riding in the upper front seat of a double-decker bus, listening to a song inside my headphones and watching the city gush beneath my yellow Doc Martens like a music video when my mother phones to tell me that the last cat has died. He was sitting on the kitchen windowsill where he always sat, she says, when suddenly he flopped, as if shot, and plummeted to the concrete.

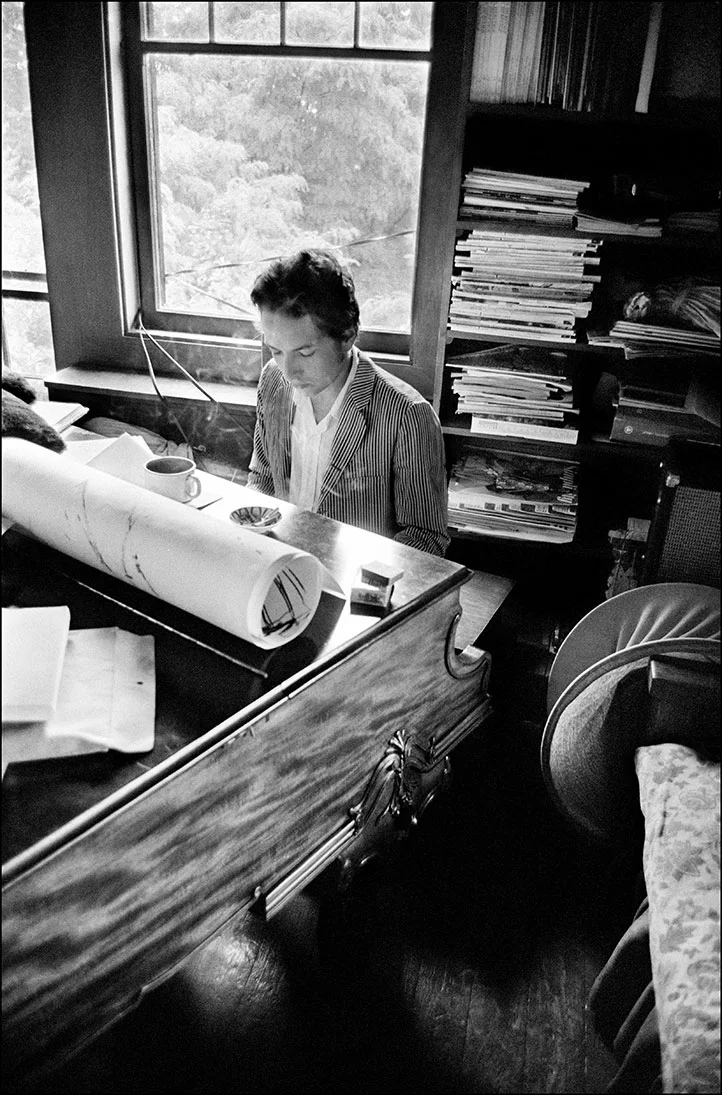

In the centre of the city where there are buskers, bars, boutiques and narrow, cobbled streets, there is a man I know – a friend of a friend – who lives on the top floor of a tall building and stays at home all day to play the piano. I’ve never been inside his flat but I stole his name and gave it to a character in a novel. He is called Simon but our shared friend calls him ‘Sigh’ because of his wistful temperament, his mournful piano-playing. I don’t understand how he is able to afford to live in the city centre; it must be that his flat is poky and dark, with dirty windows, yet I still imagine it with glass walls, sunlight spilling in, and a view of mountains.

I wear my binoculars, a dead weight against my breastbone, a tug at the back of my neck. I raise them to search for the seabird, a fulmar, that I thought I saw, but I struggle to grasp the abrupt shift of distance, the jumped kilometres, to recognise a patch of clouded sky. On the journey towards the remarkable fulmar, I find another remarkable thing: the shiny head of a seal. I lift the strap of the binoculars down from my neck and turn them around, peering backwards through the innards of the instrument, to the porthole where a disc of the view has been exquisitely miniaturised.

Balanced high above the road on the summit of a pole, a hooded crow. Even though I can hear nothing but my music and the muffled engine of my car, I can tell the crow is cawing from the way she holds her beak and body, by the tension running down her grey back. She moves as if she is throwing the sound of herself out of the tip of her beak, giving the call a flying start.

There is a solitary street lamp at a rural crossroads, alongside a brilliant white house, opposite the village shop. It is a quiet place, so quiet we draw hopscotch squares onto the tarmac and the shopkeepers’ red dogs – Ruby and Grouse – lie down and sleep in the middle of the road, but in thirty years it will be a busy place, traversed by a stream of traffic at peak times of the day, the children who I grew up with driving their own children to and from school, accelerating their silver jeeps through a mirage of multi-coloured chalk and dog ghosts.

At an exhibition opening I am standing in the glow of amber neon, holding a champagne flute and speaking to a multimedia artist who has recently become very interested in lucid dreaming. I tell him how all of my dreams are set back in the brilliant white house that never gets dark at night, in those rooms adjacent to the spotlit crossroads. He tells me that whenever he realises he is asleep but still has the power to control and conduct his actions, he immediately begins to fly.

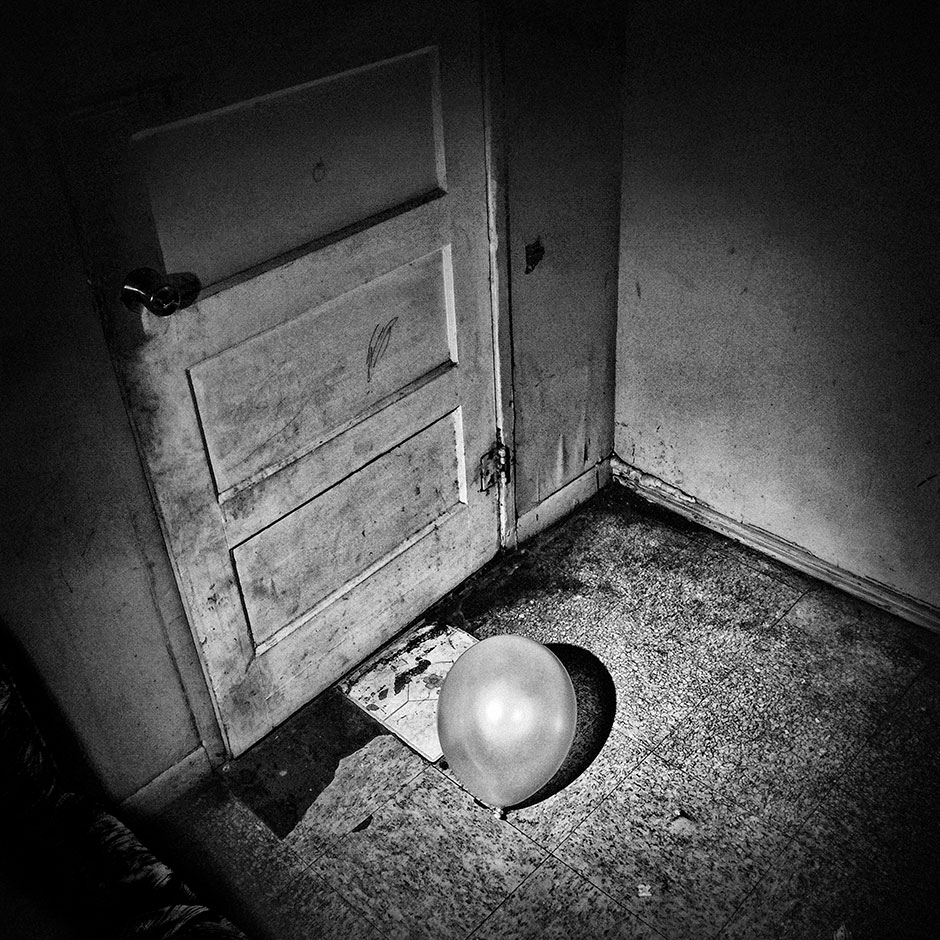

The walls of the guest bedroom are Bloody Mary red. It’s a damp room and when a guest is coming I stack domestic objects – the clothes horse, the ironing board, a rocking chair – around the perimeter to conceal the most offensive patches of mould. Noble false widow spiders nest in the cracks of the windowsill and there’s a succulent on the mantelpiece that never gets watered but survives by sipping invisible moisture out of the air. Neighbours tell me that this house almost burned down one night in the nineteen-eighties and a man was trapped inside and died of smoke inhalation. I always want to ask if they know which room it was, the one where he got trapped.

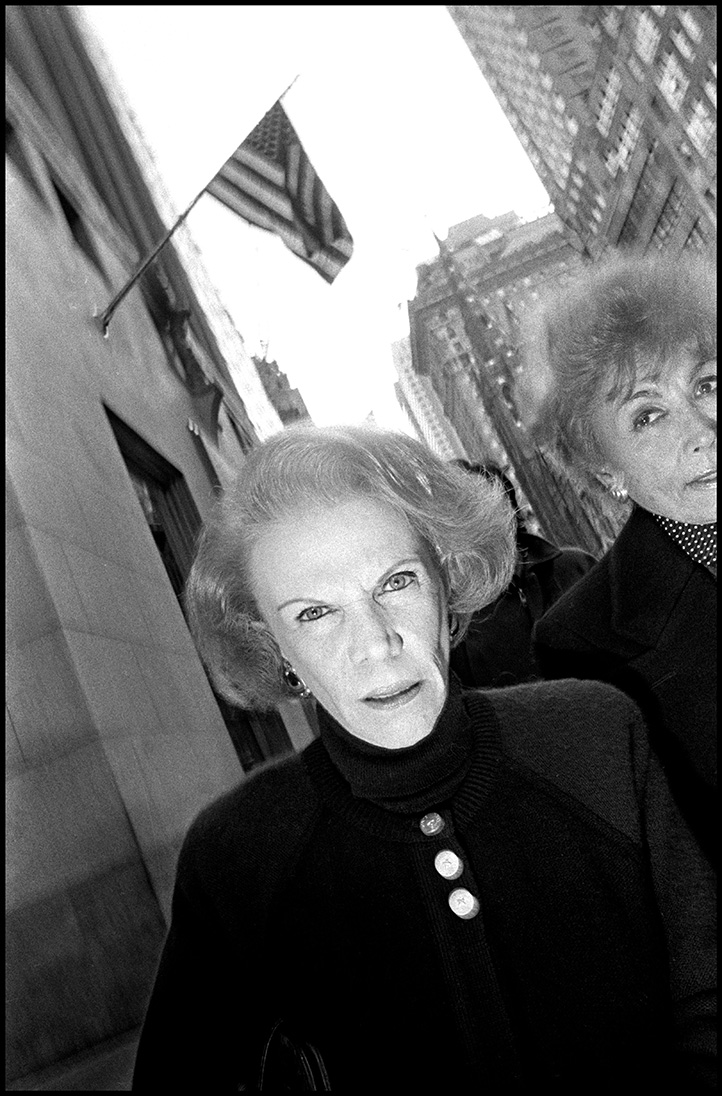

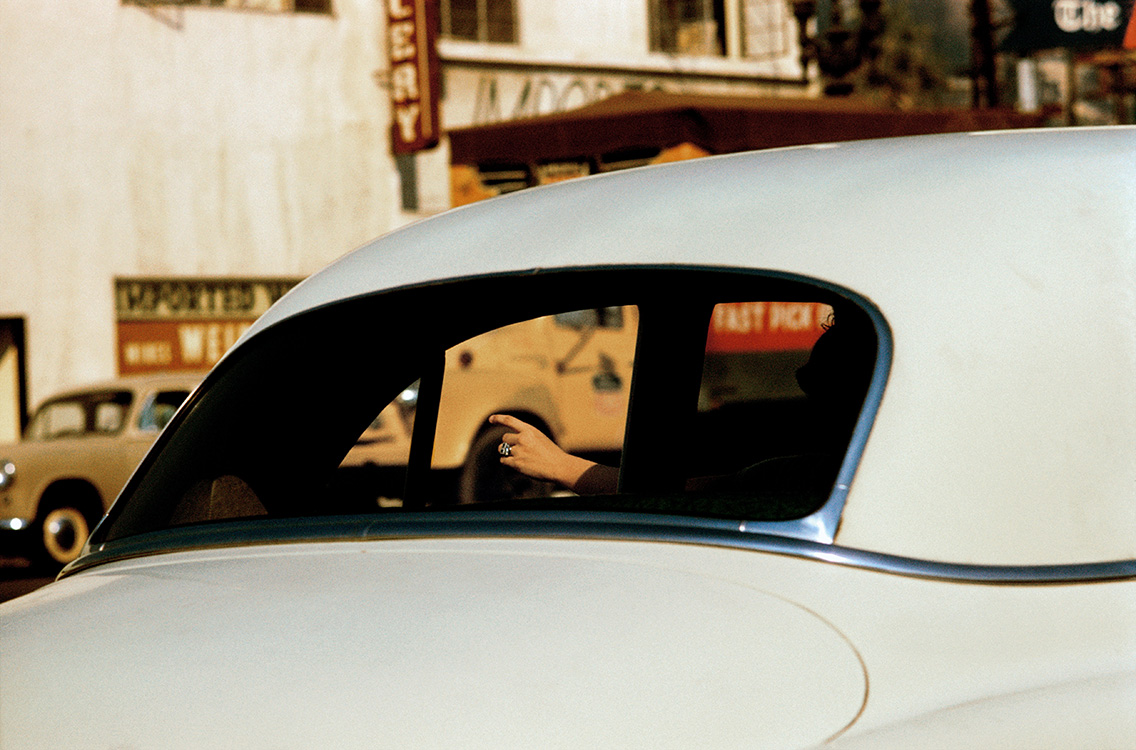

My father-in-law falls down in the street, like the cat from the windowsill. It is both late at night and early in the morning. The last time he saw his son he had tried to give him money, throwing a wad of notes through the open passenger window of the van as it began to move away, the wheels already turning, the wad unspooling and scattering across the grey upholstery and down to the rubber mats and biscuit wrappers and banana skins.

I always feel compelled to make model birds, and to paint elegant still-lives of flowers in vases against backdrops of solid colour. I have already made nearly thirty birds; they are laid out in the box room, in a line beneath a white sheet like a bird morgue, but I have never succumbed to painting a still-life of flowers; it is too sentimental, and the birds are bad enough.

For several seconds I fight against the force of seawater dragging against me, the little stones beating my skin, the slapping kelp. Afterwards I sit in the passenger seat of the van wrapped in my beach towel and think how, minutes earlier, I almost died, and yet everything is exactly the same; the same view blurring past the passenger window, the same smell of wet dog, the same satsuma peel in the pocket of the dashboard, the same shoes at the ends of my lacerated ankles, the same rain.

The dome-shaped light in the bathroom builds the suspense, hesitating for a few seconds after the switch has been pushed before coming on, followed by a single, slow blink and a noise like the sound-effect for a revelation. Its light is very soft, very general, so much so that sometimes I switch it on again, actually switching it off, without realising.

A scruffy raccoon sits on a picket fence behind a log cabin, beside a mango tree, in a garden, in America. The woman who owns the cabin, the garden, the tree, has told me that as soon as the fruit ripens a raccoon will appear and climb from branch to branch to eat as many mangoes as he can in a single sitting, using his little paws like little hands, dying his little beard yellow. They often have rabies, she says. I back away, softly, from the fence and the raccoon eyes me as if he knows implicitly that I am a foreigner; that I am afraid.

At the dog shelter there is a short-legged beagle eating from a pile of chicken necks that have been poured from a wheelie bin onto the dirt. They are skinless, bubblegum pink and slick with spit. The little dog unhinges his jaw and swallows like a snake, barely pausing for breath, consuming an incredible number of necks, his stomach ballooning, before staggering into the shade of a tree where he vomits and lies down to sleep.

On Sundays, during the country market in the city, we sell native apples out of the boot of our old car, with a sign hand-painted in green, yellow and red – apple colours – and our terrier sitting up in the back seat barking at the customers. The stall opposite is run by an impeccable Italian woman called Francesca who sells jewellery, crystals, gemstones and a natural variety of sugar that is derived from the leaves of a South American plant. She makes me taste it, dipping and licking the tip of my finger and it is so intense that I barter a big bag of apples for a little packet of sweetener.

The boot lid of my old car no longer holds itself up unaided. When I forget to extend my arm as a prop it trembles and slams, striking the back of my head or hunched shoulders. The keyhole of the driver’s door often locks all the others except the back right and boot, even this is unpredictable. The brokenness shifts, hopping from utensil to appliance to machine like a poltergeist, from the motor of my blender to the battery of my laptop, and maybe eventually to my body – a nail, a tooth, a bone, an organ.

In the brilliant white, never-dark house where all my dreams are set, there is a farm beyond the garden wall. There are bull calves being weaned and fattened for slaughter, the sound of them bawling. In the kitchen with the perpetual cat silhouette on the windowsill there’s a flypaper over the stove: a capsule of gold unspooling from the ceiling, gorgeous and honeyed and pure, like a beam of sunlight.

Somewhere in China, a weird chorus of birdsong on the street – disharmonic, distressed – so I follow the sound and find little cages running around the outside of the railings of a city garden, with bird-sellers standing in-between and on the other side, on the grass, old ladies moving their arms gently through the air, making gestures of flight in very slow motion, reaching out as if clearing a circle of space, and then rising up, flapping, soaring.

It is nearly spring. There are snowdrops, crocuses, celandine, narcissi, but not where I am standing, in the graveyard, on the concrete footpath between plots. In the graveyard the flowers are polyester, plastic and silk, and the people are clustered around a mound of wet mud, a casket, and an old man is making a speech about how he is not burying his brother today but planting him, a man-sized seed, so that maybe in the future he will grow again; he will be a kind of tree, the kind of tree that grows men.

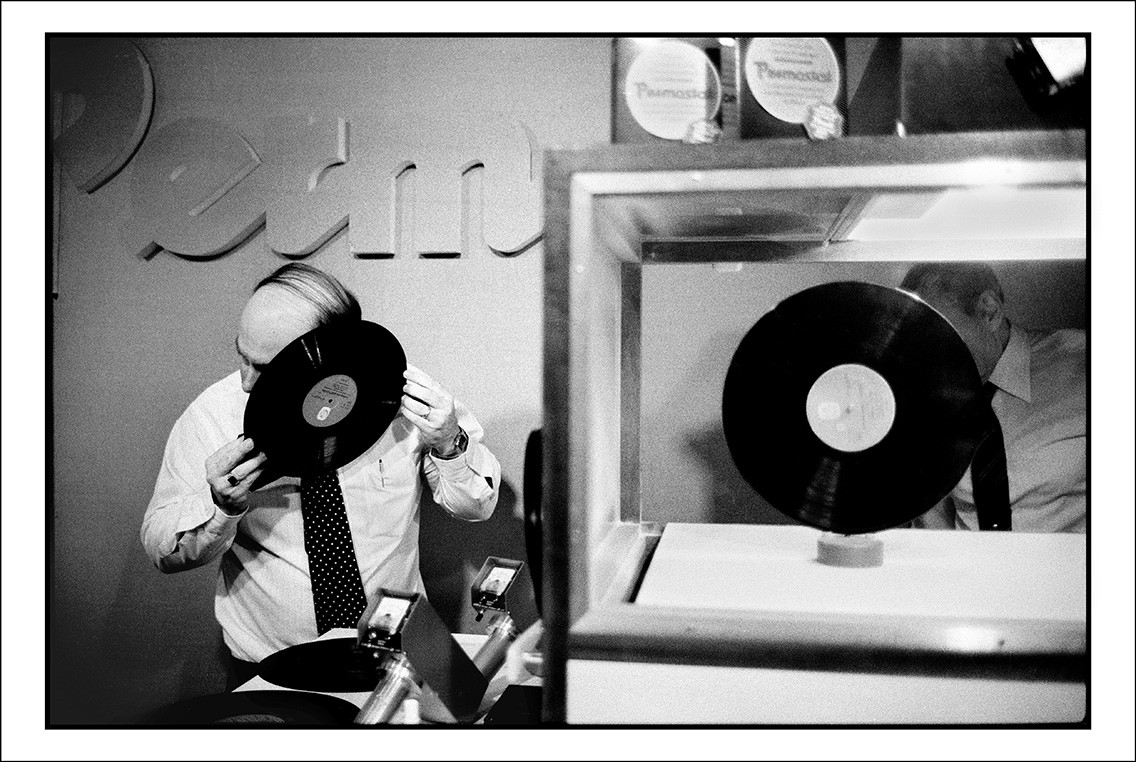

My mother’s vinyl records are, to me, at once primitive and profoundly sophisticated. I pull them from their sleeves and run my finger over the striated surfaces, trying to understand. With the money she had saved to complete her abandoned masters’ degree my mother buys a stereo player and the first time she switches it on the digital screen spells out the letters H E L L O and this seems like a miracle; as if the new machine is able to speak directly to us. Thirty years later she will still own the same stereo; it will still say hello every time it’s switched on but by then life will be too fast and too messy to wait for the greeting.

In the waiting area of the veterinary clinic a half-blind dog ambles up to where I am sitting and starts to lick my trouser leg with his husky, searching tongue. The misted, blue dome of his left eye is like a Magic 8 Ball and I feel an urge to shake the strange dog’s curved, black skull and wait for an answer to float up out of the emptiness:

outlook not so good

concentrate and ask again

signs point to yes

it is decidedly so