Thomas Ruff is a German photographer whose solo exhibition, expériences lumineuses, is showing at David Zwirner on Dover Street in London. He lives and works in Düsseldorf, where he studied at the Kunstakademie under the influential German conceptual artist Bernd Becher. Ruff is known for his systematic examination of what critics of his work frequently call ‘the grammar of photography’: he begins with subjects familiar to photography – portraits, architecture, current affairs, pornography – and seeks to interrogate how they are documented, often working with found or appropriated images.

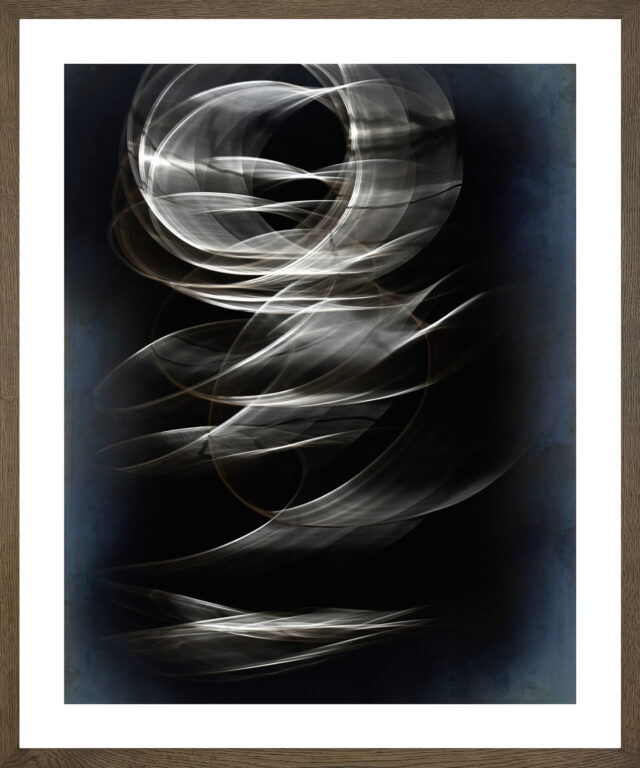

Ruff’s most recent work – much like Berenice Abbott’s early-twentieth-century experiments with light – inverts a series of photographs to show the path of light through various prisms and against mirrors. The results are displayed on a large scale, printed in a thick and textured ink onto canvas. On the day I visited, sunlight was pouring through the windows, casting precise and directional shadows across the room like one of Ruff’s prisms.

I spoke to the photographer this month about his past and present work.

– Alice Zoo

Alice Zoo:

You’ve been closely associated with the Düsseldorf School, a group of photographers who studied under Bernd and Hilla Becher at the Kunstakademie in the mid-1970s. Could you tell me about your experience there? How do you relate to the idea of the Düsseldorf School as a phenomenon?

Thomas Ruff:

I came to the art academy in Düsseldorf by chance. Back then I wanted to become a photographer for big magazines like National Geographic, famous papers featuring reportage from all around the world. I thought, perhaps naively, that an art academy would be the best place to learn how to take beautiful photographs, because that was where people made beautiful paintings. I did some research and found that most of the German academies at that time did not teach photography. Bernd Becher taught the only photography class at a German art academy that approached the medium as one would a painting class. I applied and to my surprise Bernd Becher accepted me.

It was a shock at first, because I realised when I arrived that what he was doing was the opposite of what I had been doing up until that point. By studying, I came to realise that he was right and I was wrong. I had previously been making a lot of kitsch photographs and so now I started in the tradition of sachlichkeit – objective photography. I started with interiors. We were all influenced by the Bechers. You look at Bernd and Hilla Becher’s work, and you want to understand it, to be close to it.

Before I took that class, I believed that photography captures reality, or can capture reality. But then, when I began working on the portraits, I stopped believing it. Of course, the camera records what’s in front of it, but that reality can be pre-arranged. In my case, with the portraits, I picked the person; I sometimes told them to wear this or that shirt; I made the lighting set-up; I told them to lift their chin; look up, left, right – I controlled the image.

To be honest, the photographs that we did at that time were pretty boring. We all followed Bernd Becher’s dogmatic visual approach – you were not allowed to look right or left.

For me, the nice thing was that we were part of the art academy, so I had friends studying painting, sculpture, video, all the different media. It was much more fun discussing my work with them than with my classmates. I think this helped us all to realise the advantages and limits of photography. And all of us – Andreas Gursky, Thomas Struth, Candida Höfer – were able to develop our own photographic languages. It’s funny. I cannot tell at this point who made whom famous. Did Bernd and Hilla Becher make us famous, or did the students make the Bechers famous? The hen and the egg. Who was first?

Zoo:

Did you have a sense at the time that something important was happening? When did that start becoming clear?

Ruff:

Maybe it had something to do with the taste of the art market. The art market, at the time, did not exist. We held exhibitions of our work and nothing was sold. We thought that we would have to earn a living from commissioned works, and in our free time we’d do our artistic work. But things shifted over time. Around 1980, Expressionist painting became very popular and a lot of new galleries opened. After four or five years, the interest in Expressionist paintings diminished, and then sculpture was in fashion, and when that was over, the next thing was photography. It was a new medium, and the scale of my large portraits shocked people. That was the rise of photography. It was really the right time and the right place. I don’t think that it will happen in quite that way again within the next one hundred years.

Zoo:

It often seems to me that your work is poised between the past and the future, or straddles both at once. Many of your key references – Berenice Abbott, László Moholy-Nagy – are from a century or more back. At the same time your work often pushes the boundaries of what’s currently possible (as with Fotogramme: huge photograms made in a virtual darkroom using architectural software). Do you ever feel these two directions to be in conflict?

Ruff:

Photography in the nineteenth century and at the beginning of the twentieth century was much richer than it is these days, because every photographer had to prepare their own chemicals, and papers, and the cameras were not yet standardised. Photographers used glass plates; they used paper negatives; they were painting onto the negative to print with. All that disappeared around the 1920s with the invention of the Kodak box, or the Leica. Then the photographer would just shoot with a standardised camera, with standardised film, and the film was processed and printed by somebody else. Of course, a lot of photographers were still in the dark room printing their black and white photos, but anyway – I thought that this was a loss. I like all of those different techniques from the history of photography, and I want to keep them alive. I’m trying to do my best in these times.

Zoo:

That brings us to expériences lumineuses, your most recent series, which is currently being shown at David Zwirner. Could you tell me about the beginnings of the work?

Ruff:

I wanted to make a series of very simple photographs that captured the essence of photography – just light, or light beams, and refraction in glass.

I started by buying some glass shapes and a multi-layered beam lamp used in physics lessons. Working on a concrete floor looked nice, but not interesting, so I bought more glass shapes and another lamp. Eventually I had five lamps: one side emitted five thin beams, the other two thick beams. At that point it became a game of composition: how to arrange the light going in and out, aided by a parabolic mirror that sends the light beam back into the image.

I worked in this way for a couple of months. The photographs reminded me of medical imagery, and of course the work of Berenice Abbott. At a certain point, however, I inverted the image, and something mystical happened. The white light turned into a dark line. I liked that very much, because it reminded me of charcoal, and turned the photograph into a kind of drawing. I decided then not to use photographic paper but to print the works on canvas.

Zoo:

You often describe yourself as scientific photographer. How do you relate to the idea of the mystical?

Ruff:

A good work of art, in my view, is something an artist cannot create by himself. It cannot just be constructed, because you can always deconstruct it again. Luck always plays a role. There’s something from above – I don’t know what to call it – you have to leave room for chance. You can’t follow a rigid path; you must leave space open for something else. That’s when something surprising, something different happens. I don’t know how and why – it just does.

Zoo:

It’s interesting that you mention the photographs turning into drawings. They’re printed onto canvas, and with such a lush texture that they could almost be enormous paintings.

Ruff:

I’ve been practising photography for more than forty years, always printing on photographic paper – the chromogenic print. A couple of years ago my lab told me that the large-size Kodak paper was no longer available, which is very sad. We have moved into the age of the inkjet. I will admit, though, that this has its advantages: you can print on almost any surface – paper, aluminium, even carpet, and that is very liberating.

Zoo:

Do you have thoughts on generative AI? Have you investigated it as a tool, or followed how other artists have experimented with it?

Ruff:

Right now, I’m not really interested in AI. From what I’ve seen, it doesn’t create new images. It synthesises or summarises existing images. You can tell it to make a portrait of Thomas Ruff with brown hair, two horns, and a colourful background, but that’s about it. Maybe in the future when computers start thinking, but right now they are just collecting, comparing, and then producing something based on what they’ve been fed. It cannot go beyond. Right now, I think it’s still too stupid.

Zoo:

You were in New York during 9/11, and took a series of photographs of the second tower falling from where you stood in Soho. Later, you found that the film was blank, for reasons you never discovered – perhaps wiped by airport security scans or lost to a flat battery. Your response was the series jpegs, which took images from news reports and processed them so that the pixelation made the images seem almost abstract. Would you say that limitation and constraint have been productive for you?

Ruff:

I have always been curious about the kinds of techniques that have consequences for how we look at photographs. Until 2000, we lived in the analogue world. Photographs were either printed in magazines or shown in galleries. The rise of the internet had a big impact on the distribution of photographs. Digitalisation too. It’s not only that the grain became the pixel, but that slow internet speeds required the invention of the compression rate, the JPEG. Compressing a digital image creates a new image altogether, even if you don’t recognise it when you look fast. But if you zoom in, you can see the difference between the digital world and the analogue world.

Something that has always interested me is what these photographs are doing to our brains. How do they influence us? In this time of mass distribution, you can see what Russia can do, what America can do, what AI can do. You always have to look very carefully at photographic images.

Zoo:

That feels like part of the invitation of your work: to remind us that we are looking at a photograph, and to ask us to hold the distance between image and reality a bit more firmly in mind.

You’ve spoken many times about the scientific investigations you make in your work and how each of your series works to prove a thesis. I wonder whether, over the course of your career, you feel you’ve been drawing closer to any conclusions? Are all your investigations somehow carrying you forward, the many sets of theses proved making a kind of narrative progress towards a truth or set of truths?

Ruff:

I think this work did not bring me towards many truths, because there are as many truths as there are people. Each person has their own perception, has their own cultural or social background, and their consciousness is formed by all these experiences. What I’m doing is a work of Sisyphus. It’s never-ending, because something new deconstructs something else, and just when I think I’ve found a solution, the next issue shows up. The work is just infinite.

Zoo:

Has photography changed your perception of the world?

Ruff:

I think a world without photography is possible. You don’t live with only one sense, but with a lot of different senses. And all together they form your perception and your consciousness. It’s not only photography.

Zoo:

But do you think that working in the way you have, over so many years, has had an impact on what you understand about life, or your own life?

Ruff:

No, I don’t think so. Which is pretty disappointing.

Zoo:

I read that you said photography is dead, and I wondered if you could tell me a bit about that.

Ruff:

I think I did not say that. Photography is dead?

Zoo:

It was in an interview about your series Tableaux chinois, which featured images of Mao Zedong produced by the Chinese Communist Party.

Ruff:

Well, then I would say, ‘Photography is dead, long live photography.’

Images © Thomas Ruff/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild Kunst, Germany. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner