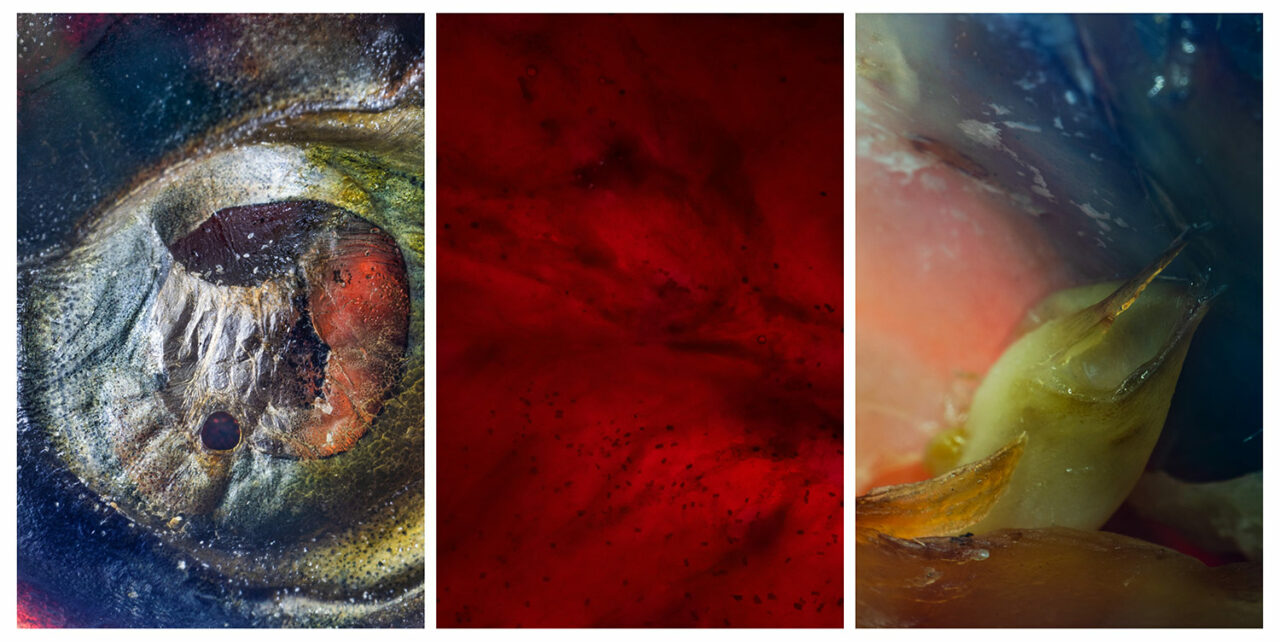

Stephen Gill is a British photographer, whose photo-book Please Notify the Sun came out in 2021. He writes that, ‘It was in 2017 that I began to have an inkling that a single fish might contain a universe of infinite proportions and how amazing a journey within its body could be.’

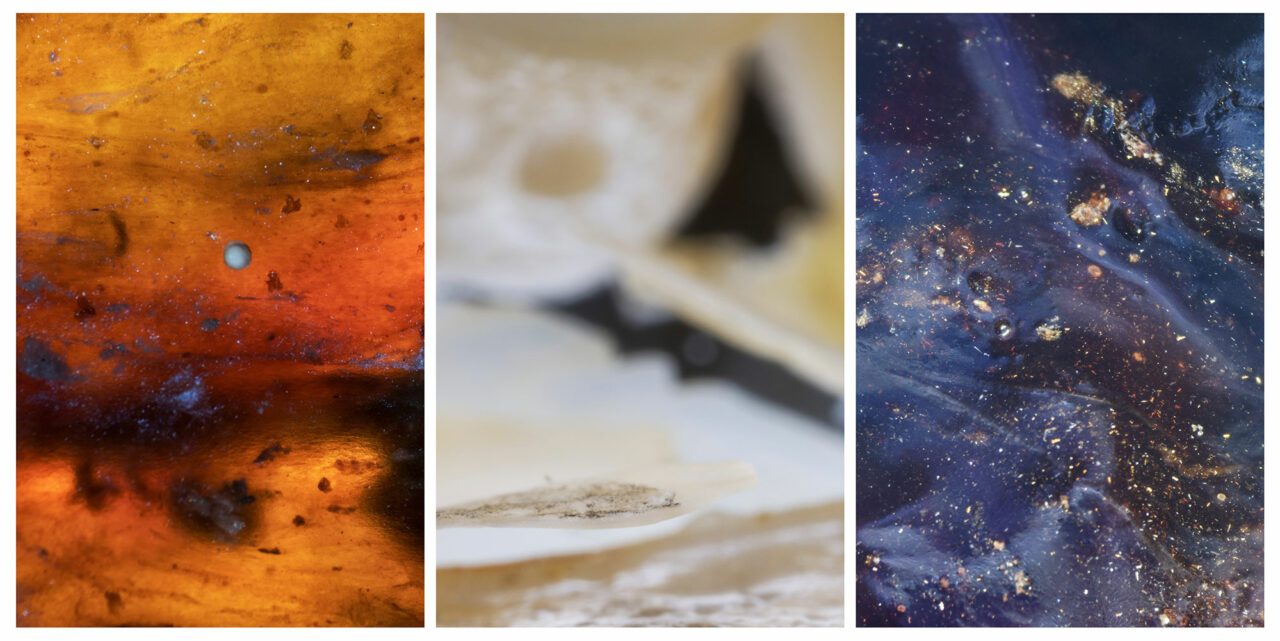

Karl Ove Knausgård, whose words accompany the images, points to the vast sense of visual possibility captured by Gill in his documenting of a single decaying fish over a period of ten weeks. ‘I see prehistoric birds,’ he writes, ‘frozen pools, a speedboat crossing a lake, a sandstorm in a desert landscape, flames of fire in darkness, craters, strange and primitive flowers.’

Granta’s photography editor, Max Ferguson, spoke to Stephen Gill about his most recent project – they discussed parallel worlds, projection and finding the control needed to embrace chaos.

When I first saw these images they reminded me of NASA’s deep-space photographs of stars and galaxies. I was surprised they were of a fish. I’m curious what you see when you look at these photographs.

I never saw fish, ever. I mean, we see what we want to see, and I was seeing stalactites, I was seeing gems. I saw the back of someone’s neck or volcanoes, volcanic lava. I mean I really saw that. I didn’t even have to work that hard to project it, you know? It was a cityscape at night from a high place. It couldn’t be anything else. I couldn’t believe it. There were times when I was shaking. But of course there are times where you wonder how much you’re pushing and projecting and how much is being emitted. I think it’s really interesting how we kind of see, to some extent, what we want to see.

You make it sound simple – it must have been a difficult to work inside of a fish?

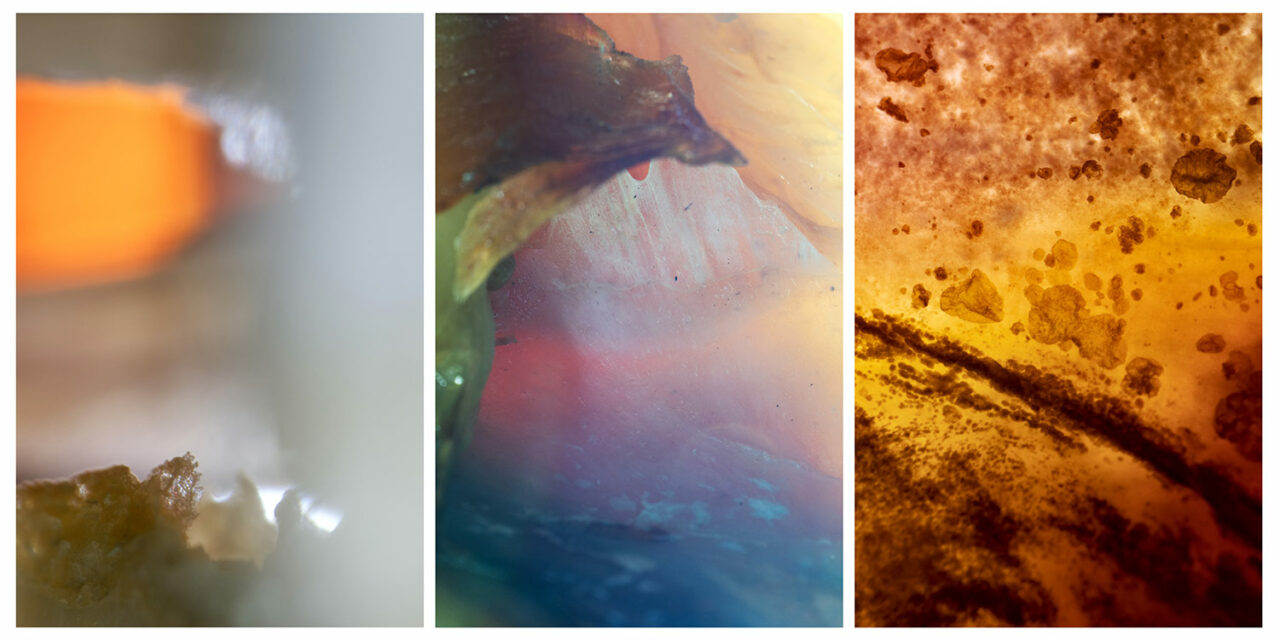

The original idea came at least three years before I started. It was bubbling. I was so sure that there would be this other world, that you could explore the inside of a fish. I imagined that I was planning a space trip. I always thought of it like a voyage or expedition – ‘one day, I’m going to go on a trip inside a fish’. But I knew the technical aspect would be the biggest hurdle and that took about two years. I was constantly on eBay, or Googling laboratory stuff or emailing universities asking to borrow their microscopic equipment and just slowly building and assembling what I needed. I bought a camera and some lenses. I hated that bit, for me it’s a real chore spending evenings on these boring things and it took about two years to build the stage or platform for the work, which had about twelve lights going underneath, and lights all around that you could move.

At that point I was completely exhausted with it, and I was also really busy with other things. It was only because of what happened during the Covid outbreak – my exhibition in Japan was cancelled and a couple of other trips – that I thought now’s the time. I thought, this is the best time for this journey – to travel, but inside a fish. And that was that. And actually it was a bit ridiculous to do it. But it was also amazing and it was probably one of the best photographic experiences I’ve had. It took ten weeks and I worked on it in nearly every day.

I’m curious how your relationship with nature has changed since you moved from London to rural Sweden?

I wasn’t aware, while in London, how much I was craving nature. I only realised when a friend pointed it out. I said to him, ‘Do you think it’s mad that I’m going to Sweden?’ He told me it made absolute sense. ‘Look at you, you’ve been craving nature for years. You did Hackney Flowers, which was all about canals, allotments and nature in cities. You photographed pigeons!’ I think I was just latching on. Maybe you could even say that something like Hackney Wick was a bit of escapism as far as me getting on my bicycle at five in the morning and cycling around the canals. And those were some of the best times I ever had in London. Just feeling you know, and seeing foxes and stuff. It was just the most amazing time.

When I moved to Sweden, I knew that nature would play a big part. But I also knew that I didn’t want to project onto it all my ideas of what nature is. I really wanted to be informed by nature. I was careful about that. Because, you know, I’ve lived in cities all my life and I didn’t want to bring anything in a way, to project anything. It had to go the other way, I had to be guided, even down to the print-making. I was using nature to help make the prints and to decide on the colour palette. But I really loved making that work, Night Procession. It’s overwhelming, this idea that while we’re sleeping there is this parallel world of wildlife as intense as anything. As intense as London.

When I think about nature at night, I might expect to see one deer roaming around, that sort of thing, but are you saying it’s really that busy?

It’s completely insane. Every square metre has so much life. But then, during daylight hours, there’s nothing. And that is really true. I kept thinking about parallel worlds. In a way, nature’s almost oblivious to us as well, even though of course, it’s affected by the things we do.

Night Procession was also made when some mad things were happening – well there are always mad things happening – but it was such a crazy time in the world, the war with Syria, for example, meaning we were reading and hearing about such terrible things happening, people drowning at sea, all at the same time as I was making those photos. You just think, there’s this whole… this parallel world completely oblivious. It was a strange conflict, it was kind of embedded in that work, even though of course, the pictures don’t reveal any of that. It was like dipping your toe into a parallel world.

Another theme in your work is control. Often, you’re relinquishing it to chance. But with these photographs it seems, to me at least, that the control has been taken back. Is that fair?

I think maybe it all started around 2001 when I started to see the potential in slippages, in denying information, and I suppose as time has gone on, twenty years on, I’ve ventured more down that path. I describe it as stepping back, as the author, and encouraging the subject to step forward. It requires a certain confidence, and maybe it comes with experience as well. It gets to a point where you feel you’ve kind of mastered your craft, or if not mastered it, then you know it so well that it’s almost second nature. And then you start to see the potentials and limitations of your medium, and you can start to dismantle everything you’ve learned. And for me, that’s when things got really exciting. And chance, of course, started to play a big part in that.

I always compare it to when musicians start to play around and detune their instruments. It means you can start to work on different levels. Even with The Pillar, let’s say, with those pictures of the birds, I was deliberately working with pictures that were all a bit wrong. Everything was a bit off. And I love thinking about that. Once you start to compile images that are all a bit off, then these new rhythms and harmonies appear. It’s about having the confidence or courage to go somewhere and stay with it.

I wanted to ask you about your relationship with the writer Karl Ove Knausgård – someone I first discovered from the essays he’s written in your last three photo books.

I think sometimes you meet people and suddenly you realise, even though there aren’t a lot of parallels in how you respond to things, that there is a strange common ground with interests or curiosities.

I also think, no matter how abstract your conversations get, it’s nice to be with people who completely get you. So you feel comfortable around each other. There’s a meeting point, even though one person is coming from a visual place, and the other from literature. And I suppose that when you’re with people who practice the same medium as yourself, not only does it sometimes get quite territorial, but also there’s a sort of suffocation within the medium, as opposed to conversations around content and subjects. My musician friends are often inspired by the visual and a lot of my visual friends are inspired by the aural. I think literature and visual arts are completely interwoven and can inform each other. And so it’s probably a healthy thing to bring different mediums together. There is, strangely, even though you wouldn’t think it, a common path, at least occasionally.

The projects we’re talking about always end up as photo-books. I’m interested in how you sequence images for these projects. How do you go through that process of making a book?

Yeah, one thing I never really do is make work with a book in mind. I work intensely on the work often for long periods of time but I try not to over-familiarise myself with the pictures while I’m making the work. You don’t want to kill it with familiarity. It’s a such a fine line, like listening to your favourite music or eating your favourite foods, you have to keep a sort of distance because you don’t want to get to know the work too much. Then you might like it for the wrong reasons, or even reject it for the wrong reasons. Then you’ve killed it through familiarity.

Sometimes though I start to piece it together in my head. But only in my mind – it’s weird. Then after a period of time, I start to make work prints and then start to assemble them. And usually this comes at a time when you feel you’ve completely exhausted the subject, or it’s exhausted you. Then I make little prints and get to know them. I put them on the table tennis table, lay them out, and try to be guided by the work. You need to let the work dictate as well.

There’s still a bit of a distance then, between the work and me, I don’t try to project too much of what’s in my head on to the work. I try to let the work emit a little bit from itself and then make these decisions when sequencing and assembling. It is a process I love. I think that’s the most fun bit in a way – assembling a body of work after years of making it. I really enjoy that.

Images © Stephen Gill