Hatty Nestor and Nathalie Olah, wrote to one another in the summer of 2021. They discussed the class system, the decline of criticism and driving on American highways.

Hatty Nestor is the author of Ethical Portraits: In Search of Representational Justice. Read an excerpt here. Nathalie Olah is the author of Steal as much as you can and her work has also appeared in the Guardian, Jacobin and the White Review.

Hatty Nestor:

Nathalie, it is such a pleasure to be corresponding with you! I have been re-reading your book Steal as much as you can recently and thinking about how it validated the experience of a generation who felt the rising effects of austerity so acutely. It is profoundly gratifying to be seen collectively in the face of disempowerment. It also made me think about how you write in your book about post-graduation life after the 2008 crash and the heavy feeling of precarity and subsequent inability to settle, whether in a job, relationship or home. Your book speaks both to this ambient current feeling and the raw political and social reality so many were subject to post-2008. A different sense of collapse happened during the pandemic, which materialised as another level of precarity for everyone, but particularly young people. I wonder if this lingering feeling has arisen for you during Covid?

On a different note, yesterday afternoon, I walked the same path I have for much of the last lockdown. I have been finding strange comfort in the familiarity, consistency and predictability of this routine, despite previously being somewhat adverse to that way of life. Yet structuring one’s time as a writer often results in patterns, rhythms and repetition. The predictability I felt in lockdown had a similar feeling to that of writing – I wonder if you have a particular routine for writing, does it feel performative?

Nathalie Olah:

It is interesting to hear you make the connection between 2008 and now. It’s difficult to assess the full economic impact as it still unfolds, but I think many young people will face the brunt in whatever measures might be imposed to ‘correct’ the economic impact of the pandemic, as you say. Though of course I hope that won’t be the case.

It’s interesting to me now reflecting on that book, because I never planned to write it and it was therefore created in a fairly unorthodox way. I was approached by the publisher Repeater to adapt an article I had written attacking a certain literary prize, which seemed to me a way for the publishing industry to repeatedly pat itself on the back and say ‘well done’ despite there being absolutely no meaningful change to the way that it is managed and the barriers it presents to people outside of a very privileged bubble. I just tried to lay down all of the thoughts and observations I’d had over the previous decade and to write it in a way that was fast-paced and (I hope) funny. All my favourite writing has that chaotic and spontaneous feel to it. Even a lot of theory is often funny and a bit stupid, unlike the boring bros who have commandeered it.

This next book did require more of a ‘process’, which is new for me and as you say – pretty hard to achieve during a time of such intense uncertainty and change. I wrote most of it early last year, while I was living alone and just pacing the same stretch of park everyday. I’m fairly sure my sanity did take a bit of a beating as a result of that, although at the same time I had just discovered Retinol, so it didn’t show on my face. When did you write Ethical Portraits, and what brought you to the subject of prisons and the justice system? Also, and this is a big one: how do you undo the naturalisation of the prison system, to get people to look beyond their own fears and biases and actually see its inherent injustices and flaws?

Nestor:

I wrote Ethical Portraits for several personal and political reasons (which are the same thing?). In my early teens, I experienced the police’s failure to implement ‘justice’ and had a family member who was institutionalised. The town I grew up in, Colchester, has one of the largest army barracks, Berechurch Hall Camp, which is the only army correction centre in the UK. Class and institutionalisation were embedded within my childhood and posed questions – just as you raise in your book – of social mobility.

Later on, I became increasingly interested in representation and investigative journalism ethics, which led me to Chelsea Manning’s case back in 2015. She remains a stark example of how the media and visibility can be severely compromised, particularly regarding gender. I wrote Ethical Portraits mainly while living in West America, visiting different prisons and interviewing many people in prison and those who worked in or for the justice system (like courtroom artists).

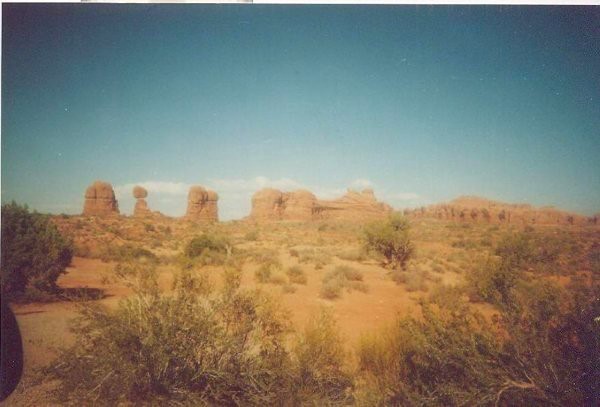

A photo of Northern New Mexico from 2017:

I really enjoyed this investigative way of working – intricately unpicking legal facts alongside ideas of who receives accountability and why. Your question about prisons is such a complex one, and I don’t know if I have the precise answer(!): the societal conditioning around prisons is so deeply societally entrenched, undoing it is multifaceted. There are so many other models for implementing ‘justice’; community accountability, restorative justice etc. But undoing our natural assumptions has to do with imagination and abolition, I think, and the space to ask – could this system otherwise?

The question of prizes is also really interesting, and the steps they create on the career ladder for writers. There are signifiers of worth built into how they function; if you are shortlisted or win one, you might get an agent or a book deal. This also makes me think of Holly Pester’s brilliant poem ‘Thirty-six’ and the performance of productivity and entrapment due to endless rent payments and capital structures. She writes ‘bound or unbound’, bearing ‘a room and a time’ but with no possibility of security save ‘marriage / or a great big prize’.

Your book made me laugh throughout, and I’ve heard I’m a tough crowd! I haven’t read anything which encapsulated my own experience so vividly while unraveling the complicated threads of taste and imposter syndrome. I was struck by how you reference studying at Oxford. I went to art school, which was more of a champagne socialist scene – so it was a different reality check about social etiquette, privilege and culture. What is the subject of your next book? What are you currently researching? I hope it is a similarly poignant – and hilarious – takedown of class and cultural capital! The question of humour seems essential, too, and is one I think about as a writer. Generally, my writing is quite serious, but I have a very dry sense of humour in person. I thought about satire while writing Ethical Portraits: do you think it really can be a social agitator?

Olah:

I don’t know if satire can lead to social change (what is it about naming a form that makes it sound so corny and impotent? I love lots of things that I guess constitute satire but I’ve really hated using the word ever since writing that chapter in the book). But I do think that art and literature can humiliate, and that can be powerful. I started to grow quite cynical in my twenties about whether change would ever come about through political education and a mass reawakening of class consciousness. The mechanisms put in place by the Tories over so many generations just seem too successful at what they do: obscuring systems of exploitation, and pitting communities against each other that should be allied. I started to subscribe to that other school of thought, that change will take place by degrading the system and the people in charge. What I especially liked in that Holly Pester poem is the line about a living space ‘naturalis[ing] tenant debt to a landlord’. It probably stuck out to me because I’ve been writing about the depiction of rentier capitalism in art recently, and the whole issue is front of mind.

Cultural studies sort of went out of fashion, and we live in a cultural climate starved of real criticism. There’s a lot of careerism going on, people doing favours for friends and scratching each other’s backs. I get the impetus, obviously, but it does contribute to a cultural industry that really can’t be trusted or relied upon to do its job. And what we lack when we let these standards deteriorate, and when we let disciplines like cultural studies disappear, is any kind of resistance to that idea of naturalisation that Barthes was first talking about, and which is absolutely necessary to the political project.

It seems very obvious to me that we have to stress that the class system really is a complete and total abomination; uncivilised and a real embarrassment for any advanced economy. Pester’s poem is doing something I really admire: it is taking something that has been so far absorbed into the logic of modern life as to seem almost inevitable, and highlighting its fairly barbaric proportions – where working people experience almost no agency or control over their lives, where even the question of love has to be weighed against economic concern.

Now at the same time in seeing a decline in criticism, we’ve also seen a really stark decline in properly reported journalism and investigation, which is something I really admired in your book. It showed real ambition at a time when that is rare. Also, by considering it through the lens of courtroom portraiture, for example, your book challenges one of the primary techniques for naturalising the entire criminal justice system. Those images are just repositories of bigotry and bias, and they prompt so many questions about shame and empathy. I was really grateful to you for opening me up to that. I thought that was really smart. Also I know it’s really famous, but I just couldn’t believe the OJ Simpson trial was broadcast for 134 days. Seems unthinkable.

America is always fascinating to me for containing so many extremes. I’ve only been to the two coasts but your stories, and this picture of New Mexico is making me wish I’d travelled further inland from California and Nevada. I like this photo I took from a sort of morbid spectacle tour of Las Vegas while staying in California a few years ago. It sort of reminded me of the Hotel Occidental in Kafka’s Amerika.

What led you to America, and to courtroom portraiture as a focus of your research? And also who influenced you in your writing? I really liked the careful balance of reportage, personal experience and cool analysis. It is really well-pitched, and many of your observations are very funny, albeit in a quiet way. I think when we write honestly, we often can’t avoid being funny. Also finally, how terrifying is it driving on American highways when there are vast juggernauts whooshing past you?

Nestor:

I love Kafka’s Amerika and the Hotel Occidental scene. The pastel blues and washed-out image of ‘New York’ in this photograph have an eerie optimism. I suppose Kafka was writing at a time when America was exotic to Europe. Despite never visiting, his capturing of its authoritarian essence is so astute. The fact that it is an ‘unfinished’ book (first called The Missing Person, and later Amerika, I think?) makes it all the more uncanny.

Driving in America was wild, particularly in a truck where the passenger door has to be pulled inwards to stop it from opening. The vast expansive plains were so profound to me, though – the space and feeling of endless possibilities. This ‘American dream’ mantra can seduce anyone, I think. But I met so many people that had been screwed over by that very warped ideal, albeit in ways that demonstrated the cruelty of capitalism and its diabolical criminal justice system in their lived experience. It is a country of extremes, polarisation and intensity!

Yes, the gradual decline of criticism and unapologetic reporting has resulted in a climate of safety and constraint. The criticality then turns to the differentiation between an echo chamber and expressing honest reflections and meditations, whether it be reviewing or opinion. I always find writers who write into that criticality, as opposed to around it, the most refreshing, closest to the political project you mention. Or perhaps the impetus to appear in certain publications shapes writer’s content – in that way, writers pursue cultural criticism, not what they really want to write about. The ongoing atmosphere created by the Tories you mention – one which starves people of culture, opportunities, and quite frankly basic human rights – naturally results in one-up-manship, career ladders and the like.

I often feel that working-class writers, even if we (as we have) get thrown a bone in the writing world, the very experience of coming from that background often isn’t expressed in the writing. Yet this experience is important material, which should be made public. Like you quote from Stuart Hall’s claim of ‘interior and exterior worlds’ in your introduction. The manifesto form of your book demonstrates that the liberatory action of accounting for experience is where political agitation might arise. The end feels like a roadmap for how working-class creatives can unapologetically find a way out of cultural and political stagnation: ‘we need more working-class audacity.’ It’s powerful!

I thought very carefully about the ethics of investigation, who speaks for who, and what it truly means to investigate other people’s lives and representation. I still don’t know if I balanced everything right (who does, when you write?). I’m glad some of the humour comes through in Ethical Portraits, even if opaquely. Creating a portrait of someone through writing – while investigating that very artistic form – was funny, both in my illustration and the perception of their work (there’s one person, in particular, this is very true of). I valued the opportunity to stay close to my subjects and how portrayal itself is an ethical act. The ability to allow yourself not to get this pursuit ‘right’ or ‘correct’ is so fundamental to this honesty you mention and bearing witness to failure and ambiguity.

I was drawn to courtroom artists because they perform a particularly complicated role in documenting trials. They provide visual testimony in the absence of the photographic images. Cameras have historically not been allowed in courts, but in 2020 a new law permitting their use was passed; meaning that soon, these jobs may become obsolete. Courtroom artists rely on high-profile cases to survive, by selling their illustrations to media outlets for capital. The drama of the justice system is fundamental to the sketches, where the role of neutrality within testimony is called into question. So there is an inherent question of worth and recognition central to these portraits, which directly feeds back into who gets represented and why.

In terms of writers, Janet Malcolm had a profound influence on my writing, for her ability to subtly expose the justice system’s flaws by depicting another. Her book The Journalist and the Murderer does this so successfully. Her writing will be cherished for generations to come, I’m sure. I am also very influenced and inspired by Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow, The Art of Cruelty by Maggie Nelson, along with David Graeber and Lynsey Hanley and Saidiya Hartman. There are so many, for different reasons!

I’d love to know the same for you – who influenced your writing, and what led you to encapsulate a whole generation’s experience of Tory austerity? It is so astutely true, so carefully captured, a portrait in its own right of a collective political, economic and social experience in Britain. I’m sitting writing after days of rain and grey – salt lamp ablaze.

Olah:

Yes, I am also interested in the ethics of investigation. Similar questions recur in lots of disciplines though – questions about depiction, the boundaries between fiction and non-, the degree of ‘omnipotence’ that an author is allowed to embody. I follow these debates and then find that I often have to disengage from them at the point when I actually want to get something down on paper. Now with writing of course we are afforded the luxury of time and redrafting, but the courtroom artist isn’t. That makes it a really fascinating medium, where prejudices have nowhere to hide.

It is always great to meet another Lynsey Hanley fan. She has influenced me a great deal. I read theory too much sometimes, and so I try to offset it with a lot of fiction and first-person non-fiction. I think you can have the most exquisite argument in the world, the most wonderful and fascinating array of facts and research findings, and yet your writing cannot help but be improved by reading someone like Eve Babitz, even if the subject matter is completely different. Someone that possesses that really fluid and natural turn of phrase. I mean James Baldwin for invective is the greatest, in my humble opinion.

And then I like to read a lot of my peers. I just finished Francisco Garcia’s book which is a great example of narrative journalism that very deftly navigates a complicated area, ethically speaking. I also really like the work of Jason Okundaye, Rachel Connolly and Rosa Lyster, all of whom I think ‘write into’ that landscape of reaction, as you put it so well. They have all provided me with a lot of lucidity on that front.

I have been meaning to read Janet Malcolm for a while, and I am especially interested in reading more by Michelle Alexander. So what are you working on now? I saw that you had worked on an exhibition catalogue and blurb – how did that happen and what is the idea of the show?

Nestor:

I thought a lot about the freedom to revise, edit and change while writing the book – the sense of control one has when writing, and that it can always be reordered and re-worked. Who has a finished version the first time round?! As you say, it is a luxury to change and revise. That is the strange ethical quandary of courtroom artists, in that they create visual testimony under pressure, which can carry with it a huge ethical weight for those they capture. They also have no recourse to change their work, which becomes very quickly public.

Lynsey Hanley is one of few writers (yourself included!) where I felt my class experience was captured astutely and clearly. From her accounts of pot noodles through to the physical placement of council estates – often on the edges of towns – and the social capital she experienced when entering sixth form were so uncanny. I have read some of the writers you mention, but I am very excited to read Jason Okundaye’s forthcoming book, and Francisco Garcia along with Amelia Horgan’s Lost in Work, are next on my list.

In Vienna, I did a ‘critics’ residency there a few years ago and have kept in touch with some of the writers and artists I met. The exhibition ‘The Will to Change’ looks at the construction of masculinity. In part through the work of Ed Fornieles and his exploration of LARP-ing (Live Action Roleplay) in ‘Cel’, where he filmed a group of people over ten days acting out alt-right politics and aggressive hierarchical structures of masculinity. I tried to write about ‘Cel’ and the performance of strength and weakness it purported. Cel is quite chilling to watch at moments because it enacts the brutalisation it seeks to critique. LARP-ing was pretty new to me, but I enjoyed thinking through those frameworks: brutalisation and resolution.

Aside from that, I am slowly researching prison privatisation in the UK, in the face of the £300 million G4S contract, who are now managing many existing prisons and building new supermax prisons. I’m investigating these new contracts and determining if there is a similarity between what happened in the US to prisons during the 1980s, while looking at true crime and the media. It feels like a very pressing time for corrections in the UK, from the new Policing, Crime, Sentencing, and Courts Bill right through to new prisons being built and the impact this is having, and will continue to have on LGBTQia+ rights. Writing about these issues feels important, even if its effect only manages to agitate or subvert, and being part of a conversation with other peers is the most helpful part of it.