Natasha Randall:

I’ve been shovelling a recent snowfall from our little road in the foothills of the Alps, clearing a way for my car, and my thoughts! I am grateful for the snow, how it clarifies every snap and tinkle here, shows me all the little birds, tamps the rustling and green.

We’re under nation-wide lockdown here in France, and so I put on a face mask when I finally got into my car (to go to the pharmacy for my son who burned his chin blowing on a flaming marshmallow yesterday). I like the feeling of the face mask – it has the same superpower as snow. When you obscure the centre-stage, the mouth, or the lively green leaves of trees, then other features and creatures can move to the fore. Have you noticed that people reach for each other with their eyes when communicating while wearing face-coverings? The exchange is intense and extra-respectful. The pharmacist searched my eyes to know the severity of the marshmallow burn, and I gave her what I could. (The burn is a little gross, I think my eyes cycled through alarm and care and prudence, then a grateful eye-smile.)

Here I have A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, which shines a bright light on a handful of Russian stories, and that light does that same thing as the snow, as the face mask. You send your beams onto a story, and an architecture rises up. You were an engineer, of course! That clarity, that mechanical faculty, is everywhere in A Swim in a Pond in the Rain. Even your title concatenates – it is a lever, playing with various densities of four-letter word.

How did you come to this title? It’s a reference to Chekhov’s ‘Gooseberries’, and your epigraph starts to explain it:

Ivan Ivanych came out of the cabin, plunged into the water with a splash and swam in the rain, thrusting his arms out wide; he raised waves on which white lilies swayed. He swam out to the middle of the river and dived and a minute later came up in another spot and swam on and kept on diving, trying to touch bottom. ‘By God!’ he kept repeating delightedly, ‘by God!’ He swam to the mill, spoke to the peasants there, and turned back and in the middle of the river lay floating, exposing his face to the rain. Burkin and Alyohin were already dressed and ready to leave, but he kept on swimming and diving. ‘By God!’ he kept exclaiming, ‘Lord have mercy on me!’

‘You’ve had enough!’ Burkin shouted to him.

Is that what we’re doing here, having a swim in a pond in the rain, and finding joy?

George Saunders:

I’m here in Oneonta, New York, with my wife and one of our daughters, and we are going to wait out the rest of the pandemic up here. This is a special place for me – it’s where I wrote most of Tenth of December and Lincoln in the Bardo. And, having finished this book on the Russians, I am back to writing stories full-time – am just wrapping up my teaching for the year and having a familiar pre-Christmas feeling of that (lovely) responsibility falling away, which leaves . . . writing. Just turned sixty-two and, more than ever, am wondering rather full-bodily: ‘What should I do with the time left?’

That’s where I am generally and philosophically although specifically I am in our basement, surrounded by workout equipment, just having finished a Zoom interview of the book (which I can only do down here, hooked up by a very short cord to Ethernet.)

Now, to your question . . . for a while the book was just called Reading the Russians or something like that, but as I was working on it I kept hoping for something better. I love that scene in ‘Gooseberries’ and have loved it since I heard Tobias Wolff reading it to a group of us grad students back around 1985. In the scene, a guy we later find out is a bit of a grouch (he makes a brilliant, persuasive speech against happiness) is . . . really happy. It’s raining and he and his friend have been trudging through the mud and now he’s naked and swimming and gets all ecstatic. We get happy just watching him be happy. And then his friend, not happy, crankily calls him back in. To me, that’s Russian lit: contradictory and very comfortable in the land of ambiguity – the Russians seemed to understand that, in a fictive narrative, the best way to make meaning is by way of opposition. The author doesn’t have to be ‘for’ anything or ‘against’ anything – he can be many things at once. And then the purpose of the story is not to judge, but to display (which we feel as a form of celebration). That’s especially true for Chekhov, I think, but can also be said about the other writers in the book – Turgenev, Gogol, Tolstoy.

Randall:

I just listened to the poet Alice Oswald on David Naimon’s brilliant podcast on my morning trudge, and she said that swimming is like writing poetry. This, from her poem, ‘A Short Story of Falling’, says more:

water which is so raw so earthy-strong

and lurks in cast-iron tanks and leaks alongdrawn under gravity towards my tongue

to cool and fill the pipe-work of this songwhich is the story of the falling rain

that rises to the light and falls again

I see all this so clearly in your title too, that a swim in a pond in the rain refers to movement, yielding, and two manifestations of water. The pond, the place of the swimming, and the rain, a tempo, water in rhythm. Water as a medium, and water in time. This is just what you examine in your book: what happens in space and what happens in time, over the course of a swim, a story.

But there is that other, real-life story that you recount in your book, another buttress to your Swim-Pond-Rain. In the 1890s, Chekhov bought a country estate a few miles from Tolstoy’s Yasnaya Polyana. Chekhov, the grandson of a serf, was now a landowner, running a farm, treating the local peasants as a doctor. It took him some time to visit his famous neighbour but, as history relates, when he finally arrived, Tolstoy was heading for a swim. He urged Chekhov to follow him to the creek and after removing his ascetic linen garb in the bathhouse, Tolstoy entered the water. He stayed there, submerged to his neck for the length of this first conversation, talking to Chekhov from the water. Thirty-something Chekhov noted that sixty-something Tolstoy’s long, white beard floated on the water. Later that evening, Tolstoy read passages from Resurrection to his guest, and Chekhov stayed the night. Was there a smell of burnt pipe tobacco that kept Chekhov awake? History doesn’t relate that. But here is that plyos, that pond!

Then, a simpler coincidence struck me: I see you, a younger writer, listening to Tobias Wolff who is reading ‘Gooseberries’, treading water, submerged in a pond. Come on in to the land of ambiguity, the water’s fine! Was that the moment you, the writer, became more free? What did the story ‘Gooseberries’ do to you that day?

One last thing about water because it’s too good to leave out: Chekhov once told Ivan Bunin that it was very hard to describe the sea. But, he said, do you know what I read in a schoolboy’s notebook the other day? ‘The sea is vast.’ That was it. And I thought it was miraculous, Chekhov said. That miracle, that miraculous brevity, is what I’m getting at here, with your Swim in a Pond in the Rain.

Saunders:

Yes – in that moment of hearing Toby read Chekhov, I could see a couple of important things. First, how entertaining Chekhov was. And that this was no accident. The whole story, especially heard aloud, was an exercise in charm – in setting up an expectation in the reader and then satisfying that, with a twist; in assuming that the reader was smart and bright and curious about, and a little in love with, life. The reading seemed like an occasion to reminds us all that, sometimes, we were in love with life – not always, but sometimes, and that was good enough. So, mostly, it filled me with aspiration (I wanted to do to a crowd what Chekhov/Toby had just done to us). And, for maybe the first time, it made me feel that the short story form was my form – more in keeping with my true self than a song or a poem or a novel or a movie script or a stand-up routine. That was exciting, that feeling that everything I knew about life or would learn about life could be subjugated to, or put into, that one form. It sort of felt like: ‘Ah, I just found out what I’ll be doing with the rest of my life.’

And I love that story about Chekhov and Bunin, and, to my ear, it underscores something important about fiction and especially about the role of description – we don’t describe something in order to be accurate or to catalog something or to prove that we’ve just come up with the perfect pithy description that will make an image explode in the reader’s mind (although those are all fine things, if we can pull them off). But the role of the description, really, is to create the Platonic notion of the thing being described and thus get the reader doing the work of picturing it in her or his own way. ‘The sea is vast’ is inarguable and, for my money, makes a reader imagine some sea (any sea) better than a half page of technical or painterly description would; it makes us supply a sea. Which the mind is pretty good at. And then, voila, the writer has a sea to work with (a sort of reader-customized sea, which is likely, then, to be more meaningful to the reader, since it’s been pre-infused with her special and subtle meanings.) Chekhov also talks about doing this in another way – providing one small detail that will then back-create the whole shebang (‘You’ll have a moonlit night if you write that on the mill dam a piece of glass from a broken bottle glittered like a bright little star.’)

But to be really honest – the way I chose the title and the way I write in general is basically just to move, in as a quiet-minded a manner as I can, toward what I feel as heat. I don’t think I have to completely understand a title’s meaning but, rather, when my mind goes to it, and sits with it for that brief second, it lights up in a nice way. Basically I’m seeking a ‘Ooh, yes, that’s nice,’ feeling. And of course, this feeling contains all of the metaphorical meanings (and the way a title or a line of prose looks on the page, and so on) but hopefully, also, a little extra and indefinable something else, that is satisfying though I might not be able to say exactly why.

PS I love David Naimon too – he’s a national treasure as an interviewer.

Randall:

The charm of Chekhov! Yes. Shostakovich said Chekhov’s prose was the most musical prose of all Russian literature – he knew many of the stories by heart, apparently. I can see it: Chekhov’s lexicon is simple but he has a terrific sense of pulse, often playing with long and short sentences like syncopations, and how he loves the ellipsis . . .

The musicality comes through, I think, in many translations, but Englishings add at least thirty per cent more words to his stories. The languages are hard to match that way, Russian words contain so much within their bounds that is broken into little English words upon translation. The compact nature of the Russian language means that, with the liberal application of prefixes and suffixes, Russian lends itself more easily to rhyme and rhythm. (Russian words are often built words, which is to say that little parts add up to one gesture.)

A rare instance in which Russian and English are similarly dextrous is the word plyos – a pool, a stretch of water – about which you include a very good footnote in your ‘Gooseberries’ chapter, explaining that it derives from pleskatsya. See here what this little root of a word, plyos, can do:

Pleskatsya = to swash, lap

Pleskat’ = splatter

Plesk = a splash, plash

Vsplesk = a fall into water with a splash

Pleskanie = a popple, a rolling or rippling of water

The Russian is giving us so many variations, but look at our seven English words about water and how they form their own little flow too:

wash, swash, splash, plash, popple, splatter, lap.

Those words sound funny. Sillier than the Russian words. But have you ever read some of Chekhov’s very early stories? They are comical and they also contribute to a rounder picture of Chekhov the writer, and Chekhov the man – a charming and funny being. So much bleak and depressing stuff sticks to him, unfairly. (If you haven’t, do read them in Rosamund Bartlett’s translation, The Exclamation Mark, Hesperus Press, 2008)

I am tempted, out of habit, to deliver a litany of observations on the words and language of the stories you examine in your book. Did Alyosha the Pot laugh or smile before he burst into tears? The translations do not agree. But I will draw back instead and say this – I gave a lecture at the Oxford Centre for Life-Writing recently about Constance Garnett in which I asked myself: can you find her, Garnett, in the texts she translated? Did she leave a trace? In the end, I concluded that translation is the closest kind of reading. I say this because what you do in A Swim in a Pond in the Rain is very close to the process of translation. Chapter after chapter, you read the Russian stories, and keep, at all times, a watch over yourself and your reaction, you walk us through a story with you. You write: ‘Where else can we go, but the pages of a story, to prefer so strongly, react without rationalization, love or hate so freely, be so radically ourselves?’

Likewise, I’m not sure you can ever describe the translator, as people like to do, as an intermediary who must strive for invisibility. It’s not possible. A translator is a reader. And then a writer. And between the reading (of the original text) and the writing (of her rendering) is a little forgetting. (This is where the traces of Constance Garnett become vapourous, less defined.)

The point is: you can’t read directly into another language. You read and contribute your own personal idiom, your memories, your biases, your associations to the text. The translator does this again and again, transmogrifies from reader to writer. She reads, she contributes to the text, she co-creates the text as a reader, as all readers do, and then she rewrites it. You reconstitute the stories, too. I loved, in your book, how you then try to recreate the act of translation with an exercise, giving us five English variations of the same Babel sentence, asking us which we prefer. You then prompt us to write our own version: ‘how would you put that across?’

This variation is marvellous to me. Saying a translation is wrong is like saying a reading is wrong – this is possible in an academic sense, there are arguments to be made on correct readings for some purposes, but crucially, without the reader, the text doesn’t become anything. (Ahem, we know this from Barthes, et al …) Every translation of ‘Gooseberries’ is valid in this regard, and every reading of it – so, it’s the witnessing that occasions the text. What’s your take, as it were, on interpretation?

Saunders:

I felt inclined here, to interject a question and comments to your previous letter –

Englishings add at least thirty percent more words to [Chekhov’s] stories. The languages are hard to match that way, Russian words contain so much within their bounds that is broken into little English words upon translation. The compact nature of the Russian language means that, with the liberal application of prefixes and suffixes, Russian lends itself more easily to rhyme and rhythm.

So would it be fair to say that Chekhov, in Russian, sounds more like a minimalist? And, to broaden that question obnoxiously – which writer in English does Chekhov most put you in mind of? And then, same question re: Gogol and Tolstoy?

One of the disclaimers I make in the book is that, since I don’t speak or read Russian, we have to sort of leave the question of translation alone and just pretend that we found these stories and read them in English, and then evaluate their merits on that basis. And, of course, we’re losing so much of the writer’s intention and vibe when we leave behind the Russian, I assume.

Have you ever read some of Chekhov’s very early stories? They are comical and they also contribute to a rounder picture of Chekhov the writer, and Chekhov the man – a charming and funny being.

I have read those early stories and am always heartened by them. It’s such an education, and reminds us (or me, anyway) that art is not ‘who we are’. It is the process by which we are ‘always trying to become’, and what we are trying to become is not (yet) ours to know. So, in essence, it’s an act of faith in the idea that we have great depths in us and that dedication to craft is the thing that will bring gifts up from that depth.

What you do in A Swim in a Pond in the Rain is very close to the process of translation. Chapter after chapter, you read the Russian stories, and keep, at all times, a watch over yourself and your reaction, you walk us through a story with you.

Yes – one of my intentions in writing the book was . . . well, I feel like saying ‘to start a ruckus’. And what I mean by that is, if I give my interpretation / reading of a story, I don’t want everyone going, ‘Oh yes, quite right.’ What is much preferable (in a class, and in general) is for a sort of well-mannered brawl to break out. There were moments during the twenty years I was teaching this class when the whole room, me included, became a single organism, trying to understand. And then each person, me included, left the classroom that much further along on his or her artistic journey. It didn’t really matter what we’d said, or ‘decided’ – just the process was enough to spur growth – that process of all of us sort of huddling around the text, in which a dead person created a totally invented person and put her or him through the paces – and then all of our minds were sparking away at that, making meaning of it all these years later, the stories subtly but markedly changing the inflection of our lives. And, of course, the end goal was that each person in the room (including me) would have been inflected by the ruckus in such a way that their her or his work got better.

Randall:

Yes, a good ruckus. I keep thinking of your curiousity, it’s just so constantly evident – your students are very lucky. This morning I saw something in the colander at the faucet of my kitchen sink and I was like: I need to tell George that raspberries are hydrophobic! That sounds absurd but what I mean is that your curiosity is very contagious.

I won’t pursue the psychological problems of raspberries, I guess, and for the sake of continuity and because I loved your question, I will say this: by today’s standards, Chekhov isn’t a minimalist – his stories read like E.E. Cummings poems but there’s plenty there. I think Gordon Lish could have used his red pen on Chekhov, to put it another way. The thing about Chekhov is that so often, important things happen offstage (in both the stories and the plays). So what you’re left with, a surface of suggestions, is the processing of that hidden, larger thing . . . Marya in the cart story, she is travelling in a cart on her way home, and the cart driver tells her about various scandals. We wonder about her relationship with Hanov who keeps passing her in his own coach, and she does too. In the end, a passing train conjures an explosive memory, and she goes home. There is a little drama, the cart almost gets washed away in the river, but it doesn’t. She almost gets into trouble with all the peasants at the inn, but she doesn’t. There is threat, but at a remove.

Who does this in, say, contemporary American literature today? I want to say DeLillo. But Chekhov is less airy and oblique in his stories. Maybe Saul Bellow, but less urban? Amy Hempel, perhaps. Tessa Hadley. William Trevor. Yiyun Li does the onstage, offstage thing too, and very deftly. Her stories have some serious heft in the offing, like Chekhov.

Tolstoy has history in his bones. His stories, to me, are weighty, and thorough. They have serious gravity, gravitas and gravitations. I’m just going to let my subconscious spit out some names as contemporary analogues because this is a really hard task . . .Colson Whitehead? Zadie Smith? Christian Kiefer? Orhan Pamuk. William Styron. Again, Yiyun Li? I also want to say William Gibson, but you have to take that big step of a century and a paradigm for that to make any sense.

But Gogol – in Gogol, almost everything happens right on stage, right? A nose appears in a loaf of bread! He front-loads everything, rolls the dice right in front of the reader. I have Mary Gaitskill, Deborah Eisenberg, Lesley Nneka Arimah, Kelly Link, Aimee Bender, a darker John Ashbery, Donald Barthelme. (This is so hard. And a dangerous task.) But you remind me of Gogol. I’m thinking of Dead Souls and Lincoln in the Bardo, and the presence, the transactions of ghosts. The altering of perceptions in stories like ‘Escape from Spiderhead’. The self-consciousness of your people. The playfulness, the grotesque. The drudgery of the fake caveman is like the drudgery of Gogol’s collegiate assessors (with the annoying and malicious co-workers too). ‘Sea Oak’ reminds me of ‘A Bewitched Place’.

But I have been trying to get to a certain question all this time (not necessarily evident to you, but it’s been happening here at my chilly corner desk in my draughty two-room cabin in between frequent invasions by my two lolloping little boys) . . . and that is: how does your training as a scientist mesh with your work as a writer? I mean science and art are conventionally considered opposites – but they meld in your work – what is the terrain like at the coincidence of the two? And if you see what I mean here, then why do you find that such an interesting place?

Saunders:

Well, the first way comes out of the experience of being an engineer but not a very good, or natural, one. I had to really work at it. So I got used to the idea of failure, I guess I’d say. I learned to work toward something, I guess I’d say. Or, I learned to be all right while being, seemingly, in the middle of a failure (good training for revising a work of fiction). And then, later, I understood writing (because of that earlier engineering training) as a form of the scientific method. You make a theory (you try something) and then . . . you see how you did. You aren’t attached to that initial idea. When it fails, that wasn’t you that failed; it was just your idea. And you have more where that came from. So you are in communication with the process, iteratively. And how do you know something has failed? By uninflectedly observing it. In writing, that means: by reading what you’ve done in as unprejudiced a mind state as you can manage; not rooting for it or against it. Like a scientist. The story isn’t you; it’s just of you.

The other thing was that it was my scientific background that got me out into the world and in over my head. I got a first job in Sumatra, doing exploration geophysics in the jungle and all of my neat, Ayn Rand-inflected ideas about the world got overturned. That was a good thing.

Randall:

You wrote: ‘the way I write in general is basically just to move, in as quiet-minded a manner as I can, toward what I feel as heat.’ In talks, you mention the black box (a story) that the reader must go through, a place of some alchemy, a crucible. And I see Schrodinger’s cat – the cat in the box with the radioactive poison who may or may not be dead, and it is our witnessing, our opening of the box, that decides its mortality. In A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, we see your systematic dissections of stories. We see the forces you measure at every turn of a narrative. We see you calculate the attraction and repulsion of characters. But above all, we come back to that witnessing of phenomenon, the witnessing of a text over time – the spirit of experiment. Can you say something about that?

Saunders:

Well, I see a story as a linear-temporal thing. We start at line one and then go to line two and so on. At every step, we’re inflected – we like it, more, or less, or are resisting, or charmed, and so on. And then ‘analysis’ is just . . . recalling that process, first of all. Then, trying to account for those inflections, and in as simple a way as possible. That’s essentially what criticism is. Well, and then articulating what just happened, and putting it, if you can, into an historical context.

Now, the big question is, how does that help us as writers? One possible answer (for certain writers): it doesn’t. In which case – those writers shouldn’t do it. And for those of us it does help (and I am one of those, for sure), we’d want to recognize that the ‘helping’ isn’t necessarily linear. We don’t go, you know, ‘I think I’ll do what Tolstoy did in “Master and Man”.’ The mechanism is subtler and more mysterious than that – I just figure that something gets brought down from our head into our ‘artistic bodies’ by the process of analyzing a story and then it’s there for us to use, often without even knowing that we’re doing so. If a musician really loved a certain song, it would be natural for her to figure out the chord changes. She won’t necessarily want to drop those changes into a thing she’s working on – but the process of learning the changes is somehow expansive. Maybe close analysis just raises some internal bar, like, ‘Wow, this Tolstoy story seems incredibly organized (by whatever means he used); I should aspire to my version of that level of organization.’

But – a question about that. In your life as a translator, have you learned anything about how these writers actually worked, day to day? That is, they didn’t leave behind much in the way of our ‘craft talks’, but do you have a sense of how, say, Chekhov, proceeded on a given day? How he revised?

Randall:

Chekhov, when he wrote letters, sometimes made his points in lists, and so I will answer your question with the same – I have an inkling that you will like to be given a list right now. So, what do we know about his writing process? Here are some things:

1. Chekhov once told Bunin that ‘one should only sit down to write when one feels totally calm.’

2. In 1886, Chekhov wrote to D.V. Grigorovitch that he didn’t remember a single story that he had spent more than twenty-four hours writing: ‘ . . . And ‘The Huntsman,’ which you liked, I wrote it in the bathing-shed! I write my stories just as reporters take notes about fires: mechanically, half-consciously, without concern for the reader or for myself . . . [I] do all I can when I write not to waste my favourite scenes and images on a story which – God knows why – I keep to myself and hide carefully.’

3. Chekhov recommended reading Harriet Beecher Stowe, especially if you’re in the mood to weep.

4. Chekhov describes his struggle over writing ‘The Steppe’: ‘To begin with I’ve taken to describing the steppe, its inhabitants, and that which I experienced in the steppe. It is a good theme, and the writing is enjoyable, but unfortunately I am out of practice in writing at length, and for fear of writing digressions, I have gone to the other extreme: each page emerges compactly, like a tiny story, images accumulate, grow dense, and, leaning onto each other, they ruin the overall effect. As a result, it is not a picture, in which all the small parts come together to form a whole, like the stars in the sky, but it is instead a diagram, a dry register of impressions. A person who writes, like you, for example, will understand me, but the reader will get bored and dismiss.’ (In a letter to Korolenko, 1888)

5. ‘A story always begins very promisingly as though I may have begun a novel; the middle is crumpled and timid, and the ending, like a short sketch, is fireworks. Inevitably, in making a story one worries above all about its framework: from a mass of heroes or semi-heroes one selects just one person – a wife or husband, who is placed against a background, painted alone, highlighted, while the others are scattered over the background like small coins, and the effect is like the heavenly vault: a big moon and, around it, a mass of very small stars. But the moon does not succeed alone for it can only be understood if the stars are also discernible, but the stars are not finished. And so, what emerges from me is not literature, but something like the patching of Trishka’s coat. What is to be done? I don’t know, I don’t know. I shall rely on the all-healing nature of time.’ (A letter to Suvorin in 1888). [Note: Trishka is a character from a fable who was tasked with mending a coat, but he wasn’t a tailor so he simply made do by snipping bits of fabric off the collar and the cuffs to patch the elbows.]

6. He used to spray turpentine in a fine spray around the edges of his desk and over various objects to help him with his cough while he worked at his desk.

7. Chekhov, workshopping. He wrote this in a postscript to Suvorin in 1890: ‘If we were to cut the zoological conversations from “The Duel” wouldn’t it make it more alive?

8. I have yet to find them, but I want to read the diaries of Chekhov’s father who goes into great detail, apparently, about everyday life at Chekhov’s estate, Melikhovo.

9. Chekhov once wrote that he might never have undertaken writing if he hadn’t been a doctor – he found it invigorating to alternate between the two pursuits.

When this pandemic is over, I have half a mind to go and find some archives and look at his corrections. So much more is visible in handwriting – don’t you agree? I mean, without the genuine drafts of Emily Dickinson’s poems, we would never have known about her punctuation – the very crucial punctuation in her poems.

I once delved into the translator Mirra Ginsburg’s archives at Columbia University – she and I both translated Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We, and there was a lot of interesting material in her papers. And I was charmed, almost to tears, seeing her workings on the translation. I felt such big kinship – like she and I were some of the only people in the whole world who had grappled with the same words and sentences. I laughed and cried my way through that archive. And then: to see Zamyatin’s own handwriting, his notes – I was ferklempt. I think I was looking for evidence of Zamyatin’s process at that time, and found that he said he was always striving to capture that one detail you might glimpse when looking out the window of a speeding car.

Is We a book you have ever connected with? (There is a lot of Gogol in We. He is a collegiate assessor, they speak in futuristic skaz – so much, so much.)

Saunders:

Responding to your last question first: We is a book I’ve had on my ‘get this soon’ list for many years. Consider it moved way up the list by your recommendation.

In Buffalo, I once got to see (and hold) Twain’s handwritten fair copy of Huck Finn. In one of the margins, you could see that he was working out how best to express a certain birdsong. Like, ‘Brr-rop. Burrop. Bbbrrop.’ (I’m completely making those up, and, actually that sounds more like a vending machine, but you see what I mean.) It is so amazing to see that these great minds are just . . .minds, trying out things. The other famous story about Twain is that, on some manuscript or another, the archivists found all sorts of obscure numbers. Proof of some arcane compositional principle? No: he was tallying his daily word count. A few thoughts on your wonderful list re. Chekhov’s writing approach:

1. I would agree but, for me, would replace ‘calm’ with ‘happy’ or ‘happyish’. And maybe ‘happy and agitated’ would suit me best, or ‘itching to praise the world by being funny about it’.

2. Am I right that, in that same letter to Grigorovitch, Chekhov basically pledged to start spending more time on his stories? That’s how I remember it and I think one can see the results in those later masterpieces, like ‘Lady with Pet Dog’ and ‘In the Ravine’ and so on.

3. I’ve never read her but intend to. She is now just behind We, I guess.

4. I love this. And it reminds me that, when a writer is talking about how she or he writes, it is always an approximation – a sort of tone poem that describes, but isn’t really, a set of descriptions. It’s more like . . . a series of screams as one goes down the waterslide. The listener can roughly understand what’s going on but is not actually experiencing it.

5. Ditto. And I find it so interesting, the difference between a) the mind state we enact when reading a piece and analyzing it and b) the mind state we enact when creating something. They seem to be very different spaces, almost unrelated. What is the translator’s mind state?

6. I am going to try this turpentine-application technique. Ack, just tried it. I can’t breathe! And now my space heater just ignited my desk. Thanks, Anton and Natasha!

7. This makes me want to work some zoological conversations INTO the piece I’m working on. As soon as the flames go out on my writing desk.

8. I really enjoyed a book by Isaac Babel’s wife (At His Side: The Last Years of Isaac Babel, by A.N. Pirozhova), in which he says that Babel hated talking about his process and that they’d worked out this routine where she would interrupt any such conversations at parties. But she also left a really intriguing description of what Babel was doing as he was working, which was, as I recall, pacing around a table on which several stacks of paper were arranged, then occasionally darting back to the table to write something down. Which makes me wonder what each of those stacks was – separate stories? Different sections of the same story? And then I guess it implies that, as he paced, he was composing and revising in his head. And when he found the right sentence . . . over to the desk he’d go. (Of course, we really don’t know.)

9. I kind of feel that way about teaching. Over the years I started getting into a certain rhythm during a semester, in which I worked hard at teaching and then felt like I could then fully indulge myself in a few days of writing. This also involved a very rich transition, at the end of the semester, from ‘I am reading other people’s work in order to form and articulate a viewpoint on it’ to ‘I can now just go back to doing my own writing exactly as I want, no defense or rationale necessary.’

Well, thanks to you and Chekhov, my writing desk has now completely burned to the ground and so I am off to build another one, out of a tree I will cut down myself, without any help from my peasants. And hey, speaking of that – have you ever seen this amazing footage of Tolstoy’s daughter, Alexandra, talking about her father, in perfect American English?

I found it a bit of a mind-blower. At one point she says that the source of the conflict between her parents was Tolstoy’s desire to lead a simpler life and, to that end, he used to (gasp) take out his own garbage and make his own bed. But, I wonder, did he pick up the dog poop in the yard and fill the bird feeder and (see above) build his own writing desk out of a tree he chopped down, from the neighbor’s yard, on the sly? I think not.

Randall:

So. I called the Fire Department in Oneonta. I was born in upstate NY so I figure, I’m a native, and they will take my call. The guy who answers the phone is like, ma’am can you tell us the circumstances of the fire. I said, it was turpentine, it’s a remedy for coughing, he was under the influence. Quickly I added: under the influence of Chekhov! He was like who is this Check-off. I was like, um, he was a doctor? He’s like does this doctor live in Syracuse? And I’m like no no no, he came from Taganrog. That’s in Maine, the guys says, this is Oneonta. I’m like: the point is – George Saunders’ desk has burned down and that is, like, a national problem. How big IS this desk? the guy asks. Look, I don’t actually know, but put it this way, George says he’d have to cut down a whole tree to replace it. Lady, the guy says, and I’ve never been called ‘lady’ before and it makes me laugh, so I say yes sir? And he puts a loose hand over the phone and talks to someone else: Sam, I got a lady here and I think she needs a saw, something to do with a treasure, at least I think that’s what she said. (So, anyway, if a guy turns up with a saw, that’s what that’s about.)

PS. Yes, exactly, it was Chekhov’s early stories that he dashed off in twenty-four hours. Those were the days when he felt that the literary community disparaged him, and excluded him. Everything changed for him soon after and he became the talk of the town. ‘My Petersburg friends and acquaintances are mad at me?’ he wrote to a friend in 1890, ‘And for what? For not having bored them enough with my presence, which has bored me for so long myself!’

But Kuprin describes Chekhov’s later working process for us: ‘During the last years Chekhov began to treat himself with ever increasing strictness and exactitude: he kept his stories for several years, continually correcting and copying them, and nevertheless in spite of such minute work, the final proofs, which came from him, were speckled throughout with signs, corrections, and insertions. In order to finish a work he had to write without tearing himself away. “If I leave a story for a long time,” he once said “I cannot make myself finish it afterwards. I have to begin again.” ’ (Translated by S. S. Koteliansky and Leonard Woolf)

These are the archives we need to find – with all the yummy corrections and signs. We will find them when this pandemic is over!

PPS. That video of Alexandra Tolstoy fairly broke my heart. So much strife in that household. Also, as someone who wears glasses, it really upset me that she put her glasses on the table with the lenses facing downwards – I wanted to reach right into YouTube and turn them over for her. I was so glad when you wrote that AT speaks in perfect American English. I saw that too – that she used a few particularly American turns of phrase. Alexandra describes herself as ‘homely’ and says her father would also ruefully say ‘if only you weren’t so homely!’ . . . and of course, this is a disparaging term in American English. A homely girl is unattractive, plain, almost ugly. But in Britain, homely is used to describe cosy cottages, fireside scenes – places more often than women. AT also used the word ‘garbage’ – which in British English would be ‘rubbish’.

I am keenly attuned to this as I am half-American and half-English, and have spent my whole life translating between those two Englishes. Despite my name I am not Russian at all! I always forget that people assume that about me. I mean, it’s a little absurd because I was actually named after Natasha Rostov in War and Peace – but that wasn’t even because my parents loved the book or anything. I don’t even think either of them has read it. When my mother was heavily pregnant with the giant baby that I was, my father decided to distract her by taking her to see the ten-hour Bondarchuk movie of War and Peace. They lived in Ithaca, New York, it was a freezing winter. My dad, a logical fellow, a theoretical physicist, decided to take his wife, a woman who interprets the world through image and color only, to see a movie. It made a peculiar kind of sense. Oddly, neither of them speak another language.

PPPS. I told you that story about my parents because you asked about the mindset of a translator and that is the beginning of an answer. To continue, I am going to follow your instructions in A Swim in a Pond in the Rain and show you, as much as possible, the process I go through in translating a paragraph. Here is the first paragraph of Gogol’s ‘The Nose’ in Russian:

Марта 25 числа случилось в Петербурге необыкновенно странное происшествие. Цирюльник Иван Яковлевич, живущий на Вознесенском проспекте (фамилия его утрачена, и даже на вывеске его — где изображен господин с запыленною щекою и надписью: ‘И кровь отворяют’ — не выставлено ничего более), цирюльник Иван Яковлевич проснулся довольно рано и услышал запах горячего хлеба. Приподнявшись немного на кровати, он увидел, что супруга его, довольно почтенная дама, очень любившая пить кофей, вынимала из печи только что испеченные хлебы.

Here is my process, translating it sentence by sentence:

On the 25th of March, an extraordinarily strange event occurred in Petersburg.

[Here I am thinking – okay, I have rearranged the clauses a little but I kept the brevity, the official undertones to this sentence. I think I’ll keep it. Seems good for now.]

The barber Ivan Yakovlevitch, residing on Vosnesensky Avenue (his last name has been lost, even from his own shingle – which depicts a man with a lathered cheek, the words ‘Blood-letting too’ and nothing more) – the barber Ivan Yaklovlevitch woke up quite early and heard the smell of hot bread.

[Now, I’m thinking, do people still even say ‘shingle’ for the sign outside a store? I think so. I will use it I think. Anyway, it is okay with me if it sounds old-fashioned because a reader will know they aren’t reading a contemporary story.]

[Also, will the English-language reader be okay with the repetition of the man’s name? It appears like that in Russian, has the effect of sounding like speech. Of course I will leave it. But maybe I will add a dash (a very Russian piece of punctuation) so that the reader doesn’t trip, but instead enjoys the repetition.]

[Should I write ‘quite early’ or ‘rather early’ or ‘early enough’ or something else?]

[Yes, Gogol here does write that the barber ‘heard the smell’ – such a Gogolian play! Many translations don’t honor it – instead writing ‘smelled the smell of fresh bread’ or somesuch. But I will stick to his strangeness and use ‘heard the smell’ (and also ‘hot bread’ instead of ‘fresh bread’).]

Slightly half-rising from his bed, he saw that his spouse, a sufficiently respectable lady, who very much loved to drink coffee, was pulling just-baked breads from the oven.

[Yes, Gogol uses ‘slightly’ and ‘half-rising’, which seems repetitive but it is his repetition so I will keep it.]

[Sufficiently? Is that the right word or is there a better synonym?]

[‘just-baked’ sounds a little weird but I think I will keep it – it is accurate, and I find ‘freshly-baked’ to be too cute.]

[I first typed ‘bread’ but then realised that he has it in the plural in Russian so I corrected it to ‘breads’. I choose not to put ‘loaves of bread’ because the Russian is much more abrupt, and merely has ‘breads’ (хлебы).]

That is almost certainly a redacted version of the undulations of translation. But does that give you an inkling of the mindset? Translation is extremely hard work – not least on the eyes, that are constantly scanning the original text, scanning dictionaries, finding their place again in the produced text, over and over. I tend to do four major drafts of a translation: the first just gets the words over from the Russian, but it reads clunky and I leave weird fragments everywhere, things to be decided later. It doesn’t read like English, it reads like a foreign language in English words. The next draft is for turning the text into actual English. The third draft compares the original Russian with the English again – how far have I strayed into readability and away from the author’s style? The fourth draft is kind of the time for synthesis, when everything comes together.

To me, translating fiction feels quite different to writing fiction, and this is mostly because in writing fiction, I find, once I have found my voice, then the cadences and music can flow, but I then have to produce story from that voice, the beats, the rhythms. In translating, you aren’t in charge of the characters or points of view or anything, but you are watching for them in the author’s rendering, and you are trying, with each draft, to get that voice down onto the page. Is it the difference between the stand-up comedian and the ventriloquist with her dummy?

PPPPS. But here is a big question for you, one I’ve been dying to ask you all along. You said that the writer needs to meet the reader on an equal footing for the whole thing to work. You say:

A story is a frank, intimate conversation between equals. We keep reading because we continue to feel respected by the writer. We feel her, over there on the production end of the process, imagining that we are as intelligent and worldly and curious as she is. Because she’s paying attention to where we are (to where she’s put us), she knows when we are ‘expecting a change’ or ‘feeling skeptical of this new development’ or ‘getting tired of this episode.’ (She also knows when she’s delighted us and that, in this state, we’re slightly more open to whatever she’ll do next.

But I’m not always sure that these great Russians create a conversation between equals. I think they have a sense of keeping it interesting, but I also think that there is an authorial grandeur to their writing. It’s something that wouldn’t get a pass in contemporary American literature, I don’t think. Take Gogol, for example, and how oddly mocking he is of his characters, and how he wrong-foots the reader sometimes. There is so much self-consciousness to his narrative. A barber hears the smell of bread? I mean, it’s beguiling and intriguing, but I don’t feel he is meeting me as an equal at the ink on the page. I think Chekhov can do the same sometimes – it’s a kind of odd disrespect for some of his characters, which adds a judginess, and makes me think the author is having a little joke at someone’s expense. It’s a kind of knowing tone. Can you see what I mean? And if so, can you see how that wouldn’t work so well for today’s writers and readers? How that might be a lesson that you would NOT want to take from them?

Saunders:

Apologies for the delay in responding. We had a big snowstorm here and my project for yesterday and much of the day before was digging out, by hand (well, by shovel) a narrow walkway to the road, so we could at least get packages.

Here’s a small fraction of the path:

When I finally got it done, I went up and took a break, and came back to a nice surprise:

Re Chekhov’s later practices – I’m relieved to hear it. If someone wrote those later stories in one sitting . . . I would find that depressing. I mean, exciting, also, but . . . depressing.

In the book I speculate that every artist uses some form or iteration plus intuition. So we’re always trying to 1) improve the quality of that intuition (that is, our openness to that quiet voice and our willingness to act on it), and 2) get more comfortable with the idea that we can and should and need to come back to a piece again and again, so that it will speak to us in all kinds of weather.

Your Gogol translation was fascinating and inspiring. For what it’s worth, that’s very much what writing prose feels like to me – making choices to increase the ambient intelligence of the piece. One of the biggest discoveries I ever made for myself was how incredibly sensitive our reading selves are to small differences in a bit of prose. So, ‘The yard was covered with snow and light fell across it in a band’ and ‘A band of light fell across the snow-covered yard’ are the same thought . . . and yet not. They make two different yards. Even the omission of single words changes the tone of the sentence and this level of care, made over the course of a story, changes the voice (and therefore the meaning) in big ways – really, in the only ways that matter. So, on one hand, this is a cause for anxiety (a single paragraph is potentially a life’s work; a Rubik’s cube of choices), but, on the other hand, it’s cause for rejoicing: it’s all choices and we get to make them, and therefore originality is always possible (always still possible, no matter how late in the game).

As for your big question in the PPPPS, re you not being ‘sure that these great Russians create a conversation between equals’. . . here’s how I see it.

Once my college roommate, who had this beautiful big BMW motorcycle, asked if I wanted to go on a ride. I said yes. We headed up to Boulder and he started going way faster than I was comfortable with and then, at one point, he passed a car even as another car was coming the opposite way – that is, as I remember it, he went right between the two cars. Then he sort of looked back at me and smiled. This was something he knew how to do, felt very comfortable doing, had done before. Now, was he respecting me? Well, I’d say yes, in the sense that he was trying to give me an unforgettable ride. (And I still remember this some forty years later, albeit, still, with a little resentment).

So, I’d say I consider this wrong-footing and judginess and that knowing tonality you mention with respect to the Russians to be, in the end, part of the grand design. That is, when we feel that, we are correct, and then we look to see if the story itself somehow ‘uses’ that reaction of ours – does the story react to our reaction? Is that reaction part of the overall fabric of our experience of the story?

For example – I have a story called ‘Al Roosten’, and Al is not likeable. I have a lot of fun at his expense throughout the story. And, at one point, he does a really mean-spirited thing. And then I have some more fun at his expense. But all along, as I wrote, I was noticing that – I knew I was doing it. And that ‘intimate communication’ I’m talking about lies in this: I assumed that if I was noticing that, the reader was noticing that too, and I knew that I had to, in my ending, make sure this aspect of the story was taken into account. In this case, this meant that all along I had also been seeding into the story sad things that had happened to him in his life, and his own attempts to internally resist his own small-mindedness. So, even though I was playing my character for laughs, I was aware of that, and was aware that you, my reader, would be aware of that – and that was all part of the fun. If I got to the end without, in some way, acknowledging the sad things that had happened to him, that would have felt like an artistic failure: my failure to be aware of that which I had done.

And in such a story, the point is sometimes exactly that movement. We start out mocking or being superior to the character and then, by the end of the story, we’ve come so far in the direction of liking or even loving the character (i.e., knowing him better) that our earlier reaction seems regrettable.

When Chekhov takes a dig at a character for our benefit, that moment enters into our experience of reading the story. We ‘note it’. And bring it forward. And that actually becomes part of the subtext of expectation that has been created. When Chekhov gives us to understand that Gurov, in ‘Lady with Pet Dog’, is a sort of predatory serial monogamist who hates his wife, we know that the story is going to be about whether Gurov will change. (And, if so, how.) Or, in ‘The Darling’, part of the fun is our growing delight at the slow reveal of her character flaw (whoever she loves, she becomes that person – mimics his interests and way of speaking and so on). And we feel Chekhov lightly mocking her, and judging – that’s why it’s funny. And then the rest of the story exists to complicate that feeling, in which we have been implicated. We come to know her better and by the end of the story, our initial (judging, mocking) reaction seems . . . small.

And we might say that this is the whole work of the story.

So, this is all part of that ‘intimate communication’ I’m talking about. The author assumes a certain relation to his character, purposely or not (he just writes something, in the heat of battle, because it’s vivid or funny or whatever) – and then he notices what he’s just said and resolves to live by it (use it).

Gogol may be a special case, since skaz seems to be all about constructing a flawed narrator, which then jangles up the usual relation between reader/writer/character. The Gogolian narrator (that guy who tells us that Ivan ‘heard’ the bread baking) causes us to look askance at him. Which disrupts the usual dynamic in which we, the reader, trust the narrator. Suddenly our tour guide seems a little insane, and yet . . . he’s still guiding us. In skaz (especially as Gogol uses it, to narrate a crazy world) we soon don’t know who to trust – the whole world is tilting. But Gogol, the author, knew this – he did it ‘on purpose’. So there’s respect and communication in that – Gogol ‘knew’ that ‘heard the smell’ would land on us oddly and that we would carry that forward as we attempt to understand the rest of the story. So Gogol the author is creating the narrator and Gogol the author is watching the reader to see how she is taking this strange narrator – Gogol the author is like a puppeteer, making his puppet walk in a strange gait, while looking out a peephole at the audience to see how they’re doing – then adjusting that gait to make it more effective. Something like that. (And, by the way, all of this assumes a rather loose definition of ‘intended’. For me, ‘I meant to do that’ is indicated by the fact: ‘I sent the story out for publication.’)

I wanted to ask you about how central the stories and novels of this period were to Russian culture, and particularly to ask what percentage of the larger population was actually reading Chekhov, Tolstoy, et al, or would, at least, have known their names. I am always feeling that literature has been downgraded in our time – is less central, essential, popular – but then . . . I wonder if that’s true. I am having trouble finding out how many copies War and Peace sold on publication in 1867 but, engineer that I am, if I could find that, I would divide it by, or maybe into, the total population of Russia at that time . . . and then we’d have something. But: what’s your sense of this? Have we gone uphill or downhill since, just in terms of the importance of reading to our culture?

Randall:

This question of tone is also a question of hope, I think. A writer who is creating from a cynical place pushes the reader away – this is my impression. The gentle mocking you describe that serves an overall effect nonetheless needs to be done with a lot of heart, and a little hope. I’m not talking about overt affection for a deeply flawed fiction-person, but, in the end, the writer can’t just dump all over a character, something more and deeper has to happen. (I don’t even mean that a flawed character has to experience a great epiphany by the end of the story and turn into a great and redeemed human – I am referring to the tonal representation of people and happenings, which may also refer to the distance at which the narrator appears to be placed?)

Your story ‘Al Roosten’ – I am so glad you brought it up, not least because it contains Al’s musings on whether his sister is homely or handsome, ding, ding, that word! – is an excellent example of this.

The thing about Al Roosten is that he’s always second-guessing himself. Those doubts help us readers to forgive him – from the first paragraph. The authorial voice inhabits his flawed and malicious thinking, but it also excuses him with a certain self-consciousness. For example, Al Roosten, on his sister: ‘A nurse at forty-five. That was a laugh. He found that laughable. Although he didn’t find it laughable. He found it admirable.’ As the story goes on, Roosten expresses regret of the mean thing (and so many other things) he has done that we continue to be interested in him.

So, Chekhov, in terms of tone: His characters pause and leave things unsaid. These gentle gaps are for the reader to fill. In terms of tone, I’m going to say there are echoes to be heard inside a Chekhov text. Chekhov’s tone is respectful, and as you describe in A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, he always pulls back from passing any judgement. He lays things out just so, the characters, their discussions, their actions – and then leaves them for you. Directors always struggle (and delight) to say whether Chekhov’s plays are comedies or tragedies. He is purported to have said something that encapsulates this himself: ‘Such a beautiful day today. Don’t know if I should drink a cup of tea or hang myself.’

Tolstoy, in terms of tone: Count Tolstoy passes judgement in his fictions. But his judginess is both evident and also tempered by the fact that it is often preaching humility and his stories often include redemption. He does not leave things unsaid like Chekhov. Also, there’s a lot of death in Tolstoy – that great equalizer – and it contributes a lot of heart to his work. (There are also so many trains.) I think the reader is always assured by Tolstoy, by his stable authorial voice threading in and out (often using trains to shift perspective!), from the subjective to the objective – and this creates space for ambiguity, for prismatic meanings. (This is the ambiguity that you write about in your book!) See this line at the end of Ivan Illych when he is on the verge of death: ‘He was having that feeling which had sometimes happened to him in a railway carriage when you think you are going forwards but you are really going backwards, and suddenly you see the truth of your direction.’ Interestingly, Tolstoy is said to have hoped for accessibility in his writing – that anyone could read his books.

So, I am going to be recklessly reductive and say that in Chekhov things are implicit, in Tolstoy things are explicit. But what of Gogol?

Gogol gives us misunderstandings – from zoom-out moments to zoom-in moments. Madness is always in the offing, close by. If there was a train passing through a Gogol story, it would certainly not be used lithely to transfer perspective as in Chekhov and Tolstoy. Gogol’s train would transmogrify, take us to a different dimension, a bewitched place.

So much is made of skaz – and indeed, Gogol lamented the fact that his stories when published in Russian lost all the ‘little Russian’ (i.e. Ukrainian) variations of words. (In one story, the many varieties of melon and pumpkin were reduced simply to ‘melon’ and ‘pumpkin’.) But what if we never knew anything about this ‘speech-like’ form called skaz that forgives all narrative anomalies? When it comes down to it: as the reader of a Gogol story, you’re in on the joke (stupid Kaka Subordinate! Stupid ‘Major’ who lost his status-symbol of a nose!), but then he mocks you too, the reader. You’re in on the joke, so you’re complicit in the system that the whole story seeks to dismantle – often the materialistic, status-oriented anxiety of Russian society. It’s a house of mirrors.

The other thing I wanted to say was that these writers are also dealing in ‘types’ – the clerk is a figure of ridicule for all of the writers we’re discussing. (I have a hunch that a lot of the stereotypes are those people who were unlikely to read these stories: peasants, workers, certain women.) But so too, is the schoolmistress figure – she is a stereotype also. Village teachers were notoriously oppressed. They were not even accepted in the villages to which they were sent. It is even lonelier than we, today, as non-Russians, realise from Chekhov’s story. Teachers were liminal beings – not belonging in either noble society or with the peasantry. Marya’s ruined flour and sugar were a big deal – teachers were incredibly low salaried. This was much discussed at the time, the unfair treatment of teachers – and it mattered to Chekhov too.

But this funny thing happened at the end of the nineteenth century. A huge initiative across Russia meant that literacy rates went from 20 per cent to 40 per cent in just fifteen years. The poor were learning to read. There is an amazing book, really the most perfect study of this question and a book I have really prized for years – called When Russia Learned to Read by Jeffrey Brooks.

Brooks tells us that these new readers weren’t necessarily reading Pushkin, Gogol, Dostoyevsky – many of them, both peasants and the urban poor, were reading folk stories, tales of crime and adventure, romance novels. There were new ‘peasant schools’ – very much, I’d imagine, the kind of place in which Marya teaches in Chekhov’s ‘In the Cart’. Brooks identifies the emancipation of the serfs in 1861 as the inception of a sharp increase in literacy among the peasantry. By the time of the Russian Revolution, literacy was at 50 per cent.

Of those 50 per cent, I don’t think a great majority were reading the likes of Chekhov and Tolstoy. To be honest, I don’t even know what proportion of the American population reads ‘serious’ literature today . . . do you?

Meanwhile, have you seen this?

It is a documentary about the college course teaching Russian literature at a maximum security juvenile correctional center. The class involves University of Virginia students and incarcerated young adults, and they read classic works by Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Pushkin and Chekhov.

Saunders:

Yes, that’s lovely, that these Russians are being taught in a correction center. I think these stories speak to any human being. And maybe they speak especially to a human being with is struggling; in that state, those big questions are no longer abstract but urgent.

It’s actually the afternoon of Christmas Eve as I write this, and so many former Christmas Eves are swimming around in my head, filled with people who are older now or gone, and ways of thinking long past, and strange gifts that were precious at the time and now are . . . who knows where? (goodbye Scuba GI Joe, goodbye Snoopy dressed as an astronaut, goodbye Hot Wheels Mini-Gas Station).

So, on this topic of respecting one’s readers – I wanted to say that one way of doing this (respecting your reader) is just to be vivid. Tolstoy’s descriptions of the preparation of the horse in ‘Master and Man’; the precision with which Chekhov makes Gurov in ‘Lady with Pet Dog’ – the fact that they make these invented things seem real – that’s what I mean by ‘vivid’.

Or, I think of some of Flannery O’Connor’s stories, in which we like exactly nobody, but O’Connor’s respect for us is there in the form of how sharp and funny and read these unlikeable people are – the respect is in the craft. We feel that O’Connor thinks we are smart. What she finds funny, we find funny. And those stories perform a very powerful moral-ethical function, even though I never ‘bond with’ any particular characters. Three obnoxious characters fight, and we don’t love any of them, but the fight still has a moral-ethical meaning – kind of like if a fight breaks out in a bar between three drunks.

Some of Mary Gaitskill’s early stories work wonderfully in this way too. We find the characters odd and feel distanced from all of them but the meaning of the story is in the internal dynamics that play out between them.

Or, we might feel respected in the precision of description, or the shapeliness of the language or its unusualness. For me the big question is something like: ‘Does the writer know where the reader is, at any given moment? Does she care?’ And the ‘knowing’ there isn’t something that is necessarily intellectual. It’s more like, ‘Does the writer know what the reader is expecting, or has been primed for? Does the writer have some idea of what the pleasures of the piece have been so far, for the reader? Will the writer take all of this into account as she makes the rest of the piece?’ So, to my mind, all of that adds up to relationship.

As for the question of how many Americans read serious literature – I remember seeing something a few years ago that posited a depressingly low number (it actually gave the number which, as I recall, was in the tens of thousands – sort of like: this is the highest number of books a literary writer can hope to sell.) Lately I’ve taken some comfort in thinking more about influence than numbers. From the people I meet at my readings, I conclude that this population is unusually active and bright and interested (and therefore influential). So, to reach even one such person might be quite a powerful thing to do. The effect of that reaching would go far beyond that one person, because of the large imprint that person’s actions have on the world.

But I do sense that serious literature has dropped a few notches in importance to Americans. This is completely anecdotal but my grandmother, who never went to college, used to read every Steinbeck book when it came out. She was a mom on the South Side of Chicago, four kids, always working so hard – but this was something she looked forward to, and not as a chore but as entertainment – a way, I’d imagine, to give context to her life. But then again – I think a writer like Colson Whitehead is reaching a lot of people, and he is brilliant and taking up the big questions. So . . . I don’t know. For me, it doesn’t matter that much – this is the thing I do best and it’s all I can do to just . . . keep doing it. And the world will take care of itself.

So – I am off to, as they say, ‘make merry’. It’s cozy here in the Catskills and there’s snow on the ground but it’s warming up outside, and I have this feeling I always get at this time of year, like: ‘OK, it begins now. The real writing, the real living. Time to grow up and be more loving and put all neurosis behind me.’

And I know how it turns out (same resolutions next year and every year) but, as they say, you can’t blame a guy for trying.

Randall:

It’s that internecine time, no man’s land. I am also moved to restart. I love a reset, almost more than anything. Draw a line in the sand. To say: that era is over! And now: now for the real life to begin. But the restarts are accumulating, and I’m wondering if I should only now just try to do slightly better than before. I would really like to be less neurotic.

Reader numbers are probably not cheering, no. I don’t even know where to look for those right now. I agree whole-heartedly with you about respecting the reader. It’s pretty much the translator’s sacrosanct task – to ask, every few words, how does this read? You have to lasso a whole big ropeful of possible mindsets that are facing your page, too.

But also, how hard does a reader have to work? I feel sympathy with readers (with myself). A book has to welcome you – make it easy for you to enter its realm. Especially in these days of high stimulation, Netflix, social media. But meanwhile, there is also the historical trust factor. We trust Tolstoy and Turgenev before we read a word of them – they are tried and tested! We also trust you, George Saunders, and when you propose a scenario at the beginning of a story, we think: I will follow him because I know it was worth it the last time.

When it comes to the Russians, though (and all foreign literature for that matter), I think there is a certain ‘otherness’ to the writing that makes us extend a little more generosity as readers. This is not my landscape, the reader might think, so I will concentrate and try to understand this world. Also, what feels fresh to non-Russian readers isn’t necessarily fresh to Russians.

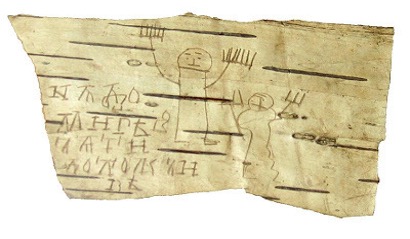

I like to read, for example, bits and pieces of ancient writing – and I love it for its strangeness. There is something so evocative, and a lot of that is owed to the context, or lack of context. Take the Novgorod Birch Bark Saga. The first BBLs (the Birch Bark Letters) were found in Veliky Novgorod in 1951, about 1,000 texts, written between the eleventh and fifteenth centuries. There are receipts, lists, wills and letters. In one of them, a man writes ‘Marry me. I want you and you, me.’ A husband asks a wife to send him clean underwear. Carved into birch bark with a metal stylus! Another letter is from a father named Onus to his son: ‘Send me a shirt, a towel, trousers, reins, and, for my sister, send fabric . . . If I am alive, I will pay for it.’

One of the oldest letters is said to translate as this:

God’s arrow, ten [is] your name

This arrow is God’s own

The Doom-God leads.

These, incidentally, were written by people who had long been considered illiterate by historians. They were written by men, women, and children too.

Now, if I saw a tweet that said ‘Marry me. I want you and you, me.’ I would think it was pretty banal – but since I know that was written by an ancient Russian fellow, on birch bark, and that it was buried in the mud for five-hundred years, something else happens with me. My imagination is fired up! Who was that ancient and logical brute?

(One of the most famous birch bark fragments was this, a young boy gets halfway through writing the alphabet but gives up and draws pictures instead.)

These BBLs aren’t ‘literature’ or ‘art’ per se . . . but they do something of the same thing. They conjure up a connection between the writer and the reader. A meeting place in the mind’s eye?

Tolstoy said it too . . . ‘To evoke in oneself a feeling one has once experienced and having evoked it in oneself then by means of movements, lines, colours, sounds, or forms expressed in words, so to transmit that feeling that others experience the same feeling – this is the activity of art.’ (Trans. Maude, 1904)

Influence is also a really interesting way of seeing the transmission of such imaginary realms – because we do pass on the stuff of literature to each other. Your active and bright and interested audience will infect others (in the good way, not the pandemic way, argh I can’t believe I have to say that). Apart from recommending books to each other, we teach each other, we tell stories, right? . . . And sometimes we write letters to each other!

Saunders:

I love that ancient little boy. You can almost see his gaze drifting out the window, the ancient little finger working its way toward his ancient little nose, just as his mother notices it and asks if he’s doing his homework and he replies that of course he is . . .

I actually found one of those birch letters just today, on my windshield. It said, ‘Don’t park your car in front of a fire hydrant, a-hole.’ And the funny thing was, this birch letter was written on an old Denny’s receipt! It was mystifying but just goes to underscore that even ancient Novogodrians could get pissy.

No, but seriously – I used to do this exercise where I had my students imitate little swaths of found text – like, for example, an interview with Madonna that had been translated into Turkish and then back into English, or an excerpt from an old foot massage textbook, or one from a diary from the Donner Party. As is the case with the (real) birch bark letters, part of the appeal is that these are not fictive documents – they are earnest and have taken on a certain stance and voice to achieve some very real objective.

And yes – I agree wholeheartedly with what you say about influence. And I think we have to be okay with not really knowing the exact nature of the influence. I like the word ‘inflected’ in this context; I was here, I read what you wrote, and then I was . . . somewhere else, slightly. My mind has been inflected. Part of the appeal is that the things we read tend to inflect us in directions in which we were already headed – they complete something, rather than wholly initiating. There’s a sort of judo-effect; good writing helps us get faster to where we are bound, maybe.

I sometimes feel a similar thing while teaching these Russian stories in real life. We’ll get on to some aspect of, say, a Tolstoy story, and as we work at it, it’s landing on each writer in a different way, per whatever he or she is struggling with in his or her own work – each person is being inflected as needed. You can feel when this is happening and it’s as if you are teaching twenty different lessons at once – just by indicating a certain place in the Tolstoy and asking the right questions. That’s a level of teaching beyond offering writing truisms (‘Show, don’t tell’) and the necessary ingredient is not really good teaching but . . . good students. Students who have done enough work on their own to have encountered a meaningful obstruction (i.e., one particular/peculiar to them) and to long for a solution to it – they are ripe for a solution, we might say.

Randall:

I would have written to you on birch bark but as I was about to strip some off a tree in the woods here, I heard a little moan from the branches above and I thought – uh oh! You don’t like being used for paper. Okay, I told the tree, I will not flay you and I will get paper from a store. (Or I’ll just email George instead.)

I worked at the Mariinsky Theater in St Petersburg once, a while ago. I was tasked with rewriting the English programmes for the ballets and operas – the synopses, the descriptions. God how I wish I had kept some of the originals. They were beautiful, in a naïve blue typeface, printed on slightly glossy but floppy and thin Soviet paper. Printed at a printing press, not by a computer printer! Anyway, they were written in a funny kind of English, and I was supposed to make them more fluent, more accurate – more like normal English. The perk was that I could sit and watch the dress rehearsals, and see Gergiev wrangling with his orchestra, see the divas have little meltdowns over uncomfortable costumes (once it was wrongly placed buttons on a coat the singer had to take off, she was very miffed about it.).

But the truth of the synopsis-editing job is that often I would read a strangely wrought sentence – and I would be so in love with its freshness that I wouldn’t want to correct it. It felt like all I was doing was making the sentence more boring. There was style, there was bumbling, there was so much in the clumsy syntax – I could feel the intellectual force of whoever had written it, and I could feel the priorities of meaning. Sometimes, I left things a little weird. Russian, after all, is a very flexible language that can be rearranged with more choreography than English. (For example, in Russian you can say ‘I love you’ but you can also say ‘I you love’ and you can also say ‘love I you’ and you can also say ‘you love I’ to mean the same thing.)

This synopsis work was part-time (I was also translating adoption documentation for the American parents of Russian orphans at the ‘House of Friendship’) and each day, after leaving the Mariinsky, I would be met by a friend. People did that in the old days, they met you at a place and time to walk home with you or get lunch. On the way to get pancakes, I would tell my friend the theater dramas of the day – and inevitably we would dissolve into mangled versions of Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin aria . . . the one that goes ‘Ya Lyublyu Vas’ (which means I love you) and which we reduced to ‘Yellow Blue Vase’ (which is what it sounds like to say). Yellow Blue Vase are also the three words that American sailors were taught to say to Russian girls when they landed in St Petersburg for a short stay.

I love the Eugene Onegin opera – but I love Pushkin’s literary original less (this is blasphemy). Also, I am sorry for the English readers who sometimes have to read it in Nabokov’s translation, which is very, very technical, uptight and anxious as a translation. Nabokov was very rude about most Russian to English translators, he was extremely disapproving of the idea that there can be ‘versions’ of a literary work. He believed in ‘fidelity’, and seemed to know what he meant by that. (I bear a grudge against him for being so dismissive about Constance Garnett.) ANYWAY, I note that you didn’t include Pushkin in your book, and there are others that didn’t make it either. I have been dying to ask you how you selected the stories you chose – and what other stories might have made the cut but didn’t in the end. Are there other stories that you like to teach?

Saunders:

I love those stories about the opera. Lovely. And the luxury of being met by a friend and walked over to lunch! Without masks and without that pre-emptive cowering I find myself doing now even when wearing a mask and approaching someone also wearing a mask!

I will never again take for granted the value of a random unwarranted conversation with a weird total stranger.

I only have one story about the arts in Russian – well, two, maybe. The first is that, back in 1981 or 1982, while I was working in the oilfields, I took one of my two-week breaks in Russia. I had, then as now, certain romantic notions about the country. It was hard for Americans to get in at that time, but somehow, because I was applying for the visa from Singapore, it was easier. I was staying at the Metropole and went down to lunch. I was seated at a common table with two men a little older than me, who were drinking vodka and invited me to join them. I did so. Then a much older and very handsome man joined us and the effect on the two young men was . . . impossible to describe. They stood, they sat, they stood, they bowed, they sputtered. The older man generously indicated that they should be at ease. They offered him vodka, he accepted, and we were off to the races. At one point, one of the young men turned to me and said that this man was an actor, a great, famous – the most famous actor in Russia . . . ‘the Russian Jimmy Stewart’, he said. The drinking went on and on. I was supposed to meet some friends that evening so at one point I excused myself and went upstairs and lay in an ice-cold bath to sober up. Ah youth! A time to be an idiot. But I always wondered who that actor was . . . any thoughts? This was, as I say, 1981 or so and he was about sixty years old, I’d say. Although, with all the drinking he appeared to be totally comfortable doing, he may have been, you know, forty.

The second story is just that, many years later (in the 2000s), when I was there as part of the St Petersburg Literary Seminar, I went to the Bolshoi Ballet. All I remember about it is that 1) it was lovely and 2) the French Horn player kept dozing off in the pit. I found that kind of beautiful. Presumably, he’d wake up, or somebody would wake him up, when it was time for him to play. He was very comfortable, being the French horn player for the Bolshoi. It was no big deal to him.

Oh, and also (a third artistic story), on that earlier trip, I went to the opera and got chewed out by a very big old man, beautifully dressed, in elaborate Russian, as his wife tried to get him to cool down. But – I deserved it. I had come right from Singapore and didn’t have any appropriate clothes, and so I was (inset cringe here) wearing overalls. WHITE overalls. But a nice shirt under it! At first I thought he was yelling at me about being a capitalist pig, but in the crowd that gathered, someone who spoke English cleared that up for me: he was yelling at me for being, simply, a pig. It was funny because even as he was yelling at me, I was kind of like, ‘Oh, sure, I see his point. What a dope I am.’ But I was also noticing that no amount of apologizing through our interlocutor on my part was causing the old guy to get any calmer.

A first harbinger, there at twenty-three years old, that my perception of the world and the world as it was were not in sync, exactly.