To begin with – a sequence of photographs. Pictures which to every beholder will ring a different set of distant bells. Light, colours, landscape, faces – they all trigger memories, and memories make connections, each of them differently. I prefer my gaze to be unencumbered by expectation or knowledge. Free to find its own little hook to latch on to, the fragment to engage with, the resurfacing memory to abandon itself to. But what is an unencumbered gaze? And where does it begin to see?

I see a road, a dual carriageway, yellow street signs, a few cars. A road of departure, arrival, passage. A road that could be anywhere – anywhere in Germany. Having grown up in Germany, I’m inevitably reminded of similar roads lined by woodland in the bleak season, without a view ahead. Through the photographer’s eye I see the road from above. Perhaps from a footbridge, linking woodland and woodland. An unsteady structure, swaying under gusts of wind, shaking when a heavy lorry passes underneath. The surface is coarse, creaking and trembling underfoot. I grew up in a land of shuddering footbridges spanning expressways, and I remember the thud of feet on those bridges, running. I remember the flat yellow of road signs like the one on the picture, and a river, a floodplain, rows of poplars, the fringes of a town. Walls of rough concrete marked by time and weather, steel railings colder than ice, and fires in early winter when the dead leaves were burned.

I’d like to be a blank surface for the pictures to impress themselves on. But unlike recalling, forgetting is not a question of effort. The remembered thud of feet running on a footbridge in my childhood comes up against a name I couldn’t help taking in: Khartoum.

Here, in this land of footbridges, woodland and concrete walls, the daylight is vague and grey; it blurs edges and brings out the solitude of a red window frame and the helplessness of purple creeper foliage while the leafless crowns of trees melt into the vagueness. It’s a light that sits oddly next to the sound of Khartoum, which I imagine to be infused with hues of yellow, orange and red, perhaps a little hazy with desert dust.

The light around the woodland is familiar to me, it instantly brings back memories of childhood winters. Whether I like it or not, they’re there, emerging unbidden along with words like ‘clammy’ and ‘black ice’. But there’s something to be said for this light too: it’s an even light, muted and shadowless; it lets things come into their own in a quiet way. No weighing of sharp contrasts between light and dark, no assessment of shadows. Even the coarse concrete seems less stark than it would in the sunshine; it looks porous, as if a soft crackle ran through the texture every now and then, the wintery sighs of lifeless matter. This light without shadows may become a photographer’s friend, regardless of the cold and in spite of its foreignness in the face of the name Khartoum.

The muted light seeps through the windows into rooms that speak of a life led around desk, clutter, house plants and bed. It spreads over the objects, smooth surfaces and the textures of fabrics; it finds itself reflected in the wooden floor, and, however feeble, it manages to infuse the cloth hanging above the bed, the curtain and the fingery leaves of the house plant, with warmth and colour. It encourages an exchange between the patches in orange and yellow within and the little shreds of autumnal red on branches outside the window, a low-key chatter, familial.

My gaze is moving back and forth between the pictures, trying to find links and threads between objects and views. Is there a conversation among the colours, the warm and the cold ones trying to find common ground? A common language? I’m wondering if the spaces framed by the lens – outside, inside, cold space, warm space – are in a city, a town, a village? No clues. Do the spaces relate to the woman who appears in three of the photographs, the obvious you to the I and eye behind the lens? Once, she’s a haloed figure, wrapped up in winter clothes. Then she’s inside, arms crossed, shoulders tense, her face unsheltered. Is she cold? Defiant? Angry? Sad? The space around her is contracting. Next there’s a close-up of the back of her head with hardly any space left between the lens and herself. This view of her short hair, her ear, her cheekbone, blurred and pale, adds a colour of tenderness to the sequence. And some melancholy too.And what about herself? This time she won’t meet the gaze of the lens. Is her head bent over a book? Writing? Shards? No clues.

The reds and yellows in the pictures guide the gaze. Yellow is the cloth on the wall that seems to say: home. Orange is the colour that defies the cold. There are the leaves of the house plant, the poster on the wall. The halo of the wrapped-up figure in the night. Copper is the colour of the woman’s hair in the close-up. Points of reference that hold their own against the grey light and the cold. But silence hangs in the air. I imagine words curling on the speakers’ lips and falling to the ground with a dull little clack. Someone will have to sweep them up at some point.

There’s a second place name I’ve learned by now, besides Khartoum: Marienhölzung. Hölzung is a beautiful, ancient word, denoting a small area of woodland, a copse. It’s a rare word, endangered like some birds and butterflies. Marienhölzung means: Marie’s woodland. I know that the photographer’s name is Muhammad. And what about the woman? She too wants a name, a name for her wrapped-up figure in the night, for her face, for the back of her head, her short hair, her cheekbone and ear. I’d call her Marie. That would make the pictures of her Marienbilder in German, pictures of Marie, not to be confused with images of the Virgin Mary, regardless of her halo in the winter night outside. Muhammad the photographer is looking at Marie, he’s probing her image, exploring spaces around Marie and her Hölzung; he a stranger to this grey light, she wary, hesitant, perhaps, to let him partake of her winter.

Do the pictures want to tell a tale, say, of an arrival, an encounter, of the winter cold and a void? Or is it only my gaze that wants to read this tale, or at least an account of varying degrees of closeness and of separation? Every lens frames the world, and for a while we as beholders look and name and draw or jump to conclusions as if the frame were the world. My eye wanders from one rectangular view of a life to the next – no, it’s two lives: one of the seeing and one of the seen, and both remain a mystery. As so often when I look at the faces of people on photographs I’m briefly stunned by the thought that I as the beholder, a nameless nobody outside Marie’s life, will never know what her gaze, so deceptively directed at me, perceives.

That’s perhaps where a story could set in, a story that would be determined as much by my sense of cold and warm and light and colour and space as by the photographer’s choice of frame. The story would be brief but inevitable, arising from the deeply human desire to connect the dots on a mental map. A map which unfolds whenever memories have been stirred from their sleep by a particular light, colour, or sound. Memories want to speak.

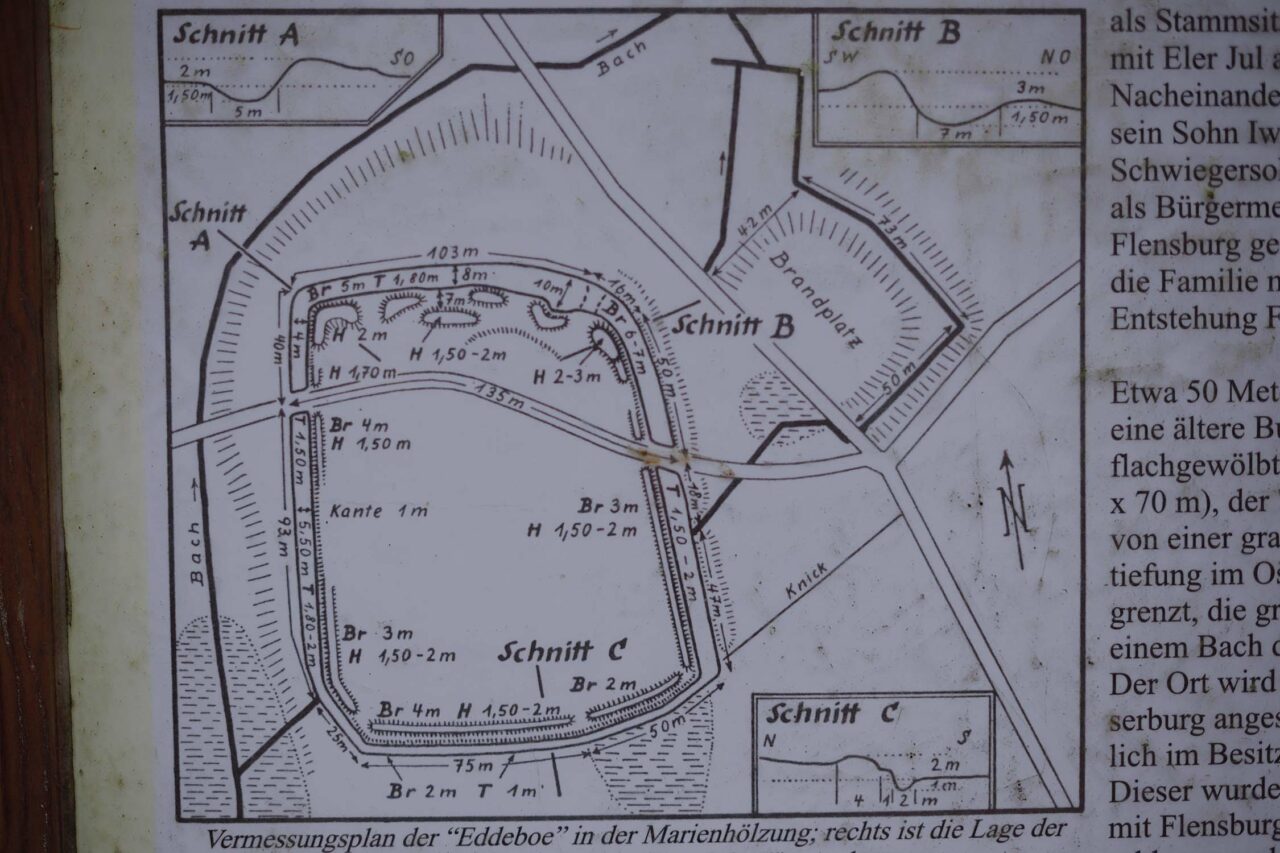

And – speaking of maps – how does the final picture wrap up the sequence? This close-up of an old map, apparently of a part of Marienhölzung, Marie’s woodland. Vaguely reminiscent of a map for a treasure hunt in a children’s book, it shows the course of a brook, dashed patches for moors and a prominent Brandplatz. Another ancient-sounding name. Brandplatz indicates a place for burning. Is it this map Marie is looking at while the lens and the eye behind it dwell on the back of her head, her ear and her cheekbone? Is she looking for clues – to find a treasure or to bury one, or for a place to light a fire, a wild flush of orange in the muted light of winter, to consume mementoes, to cut through the clamminess, to distract from the thud of feet running on the footbridge?

The tale takes us to a place for burning, but not to an ending. It takes us to a map, and maps are always about beginnings.