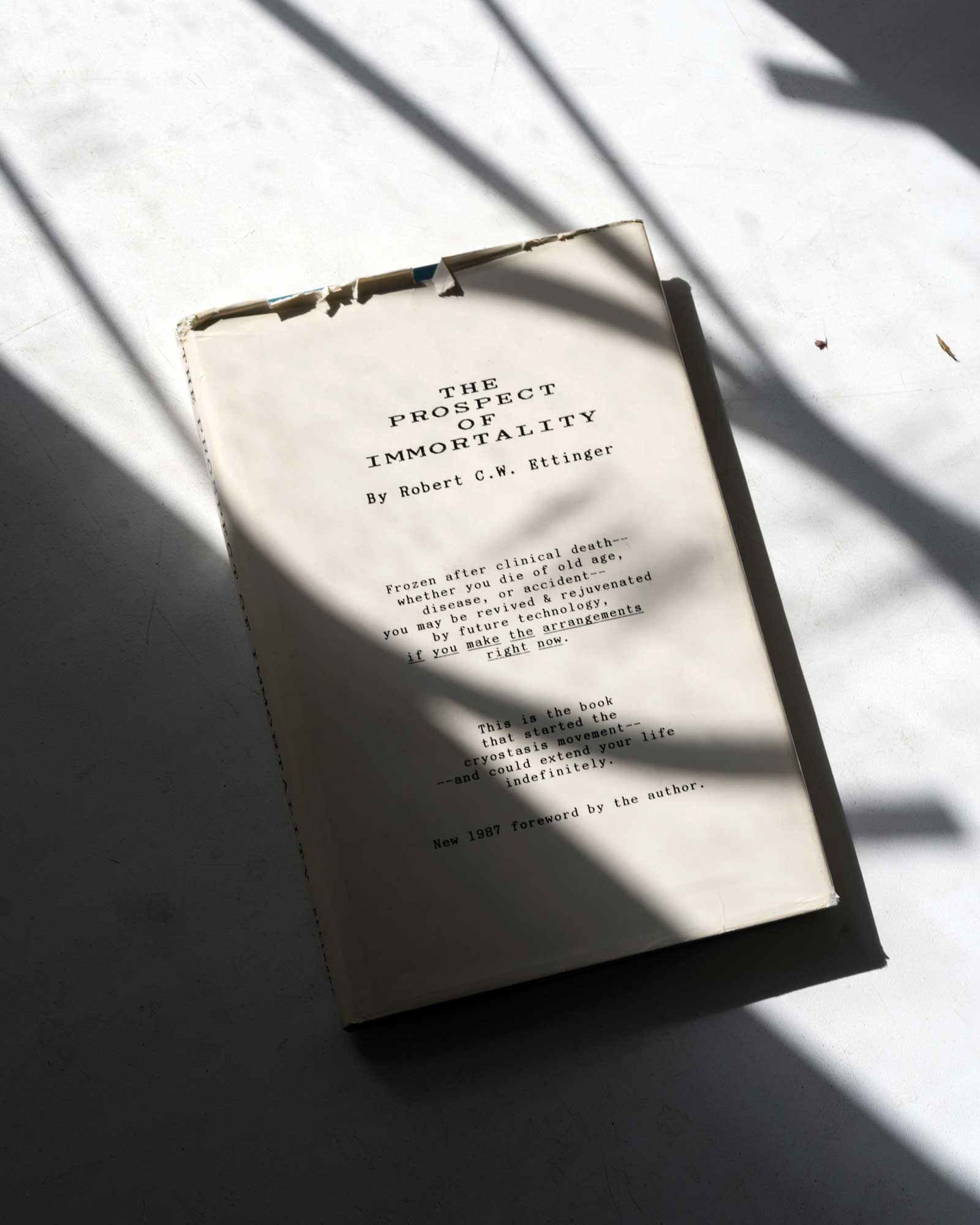

H+ refers to transhumanism: a movement based on the idea that the human body can be improved on through scientific advancement. In the Anthropocene, nothing on Earth remains untouched by human scientific advancement: in Gafsou’s H+, a map of augmented humanity threatens to become a transcription of everything. Gafsou’s intention to map the techno-human is a vague, dreamy one, like something imagined by Jorge Luis Borges, but the resulting images are lucid and hyperreal. Seen as a collection, Gafsou’s photographs gather a whole population of seemingly different technological bodies together. What links the astronaut to the pacemaker; an eighteenth-century orthotic corset to a smartphone; a lab rat to a Google mug? Gafsou gives little sense of setting or context, nobody comes or goes anywhere. Each free-floating image can only position itself in relation to the others. Not so much, then, like the kind of paper map which describes the contours of a landscape. More like a smartphone pin drop.

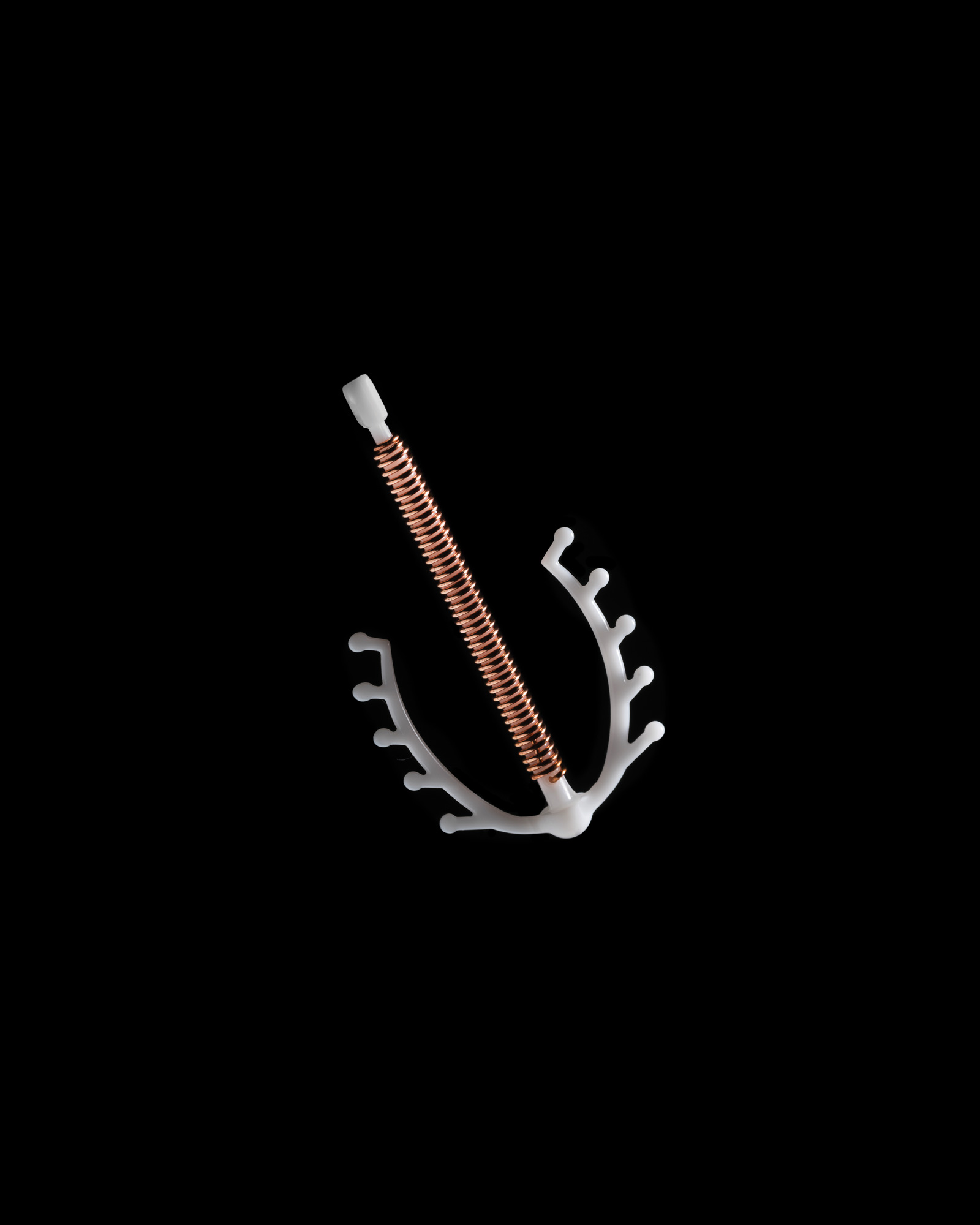

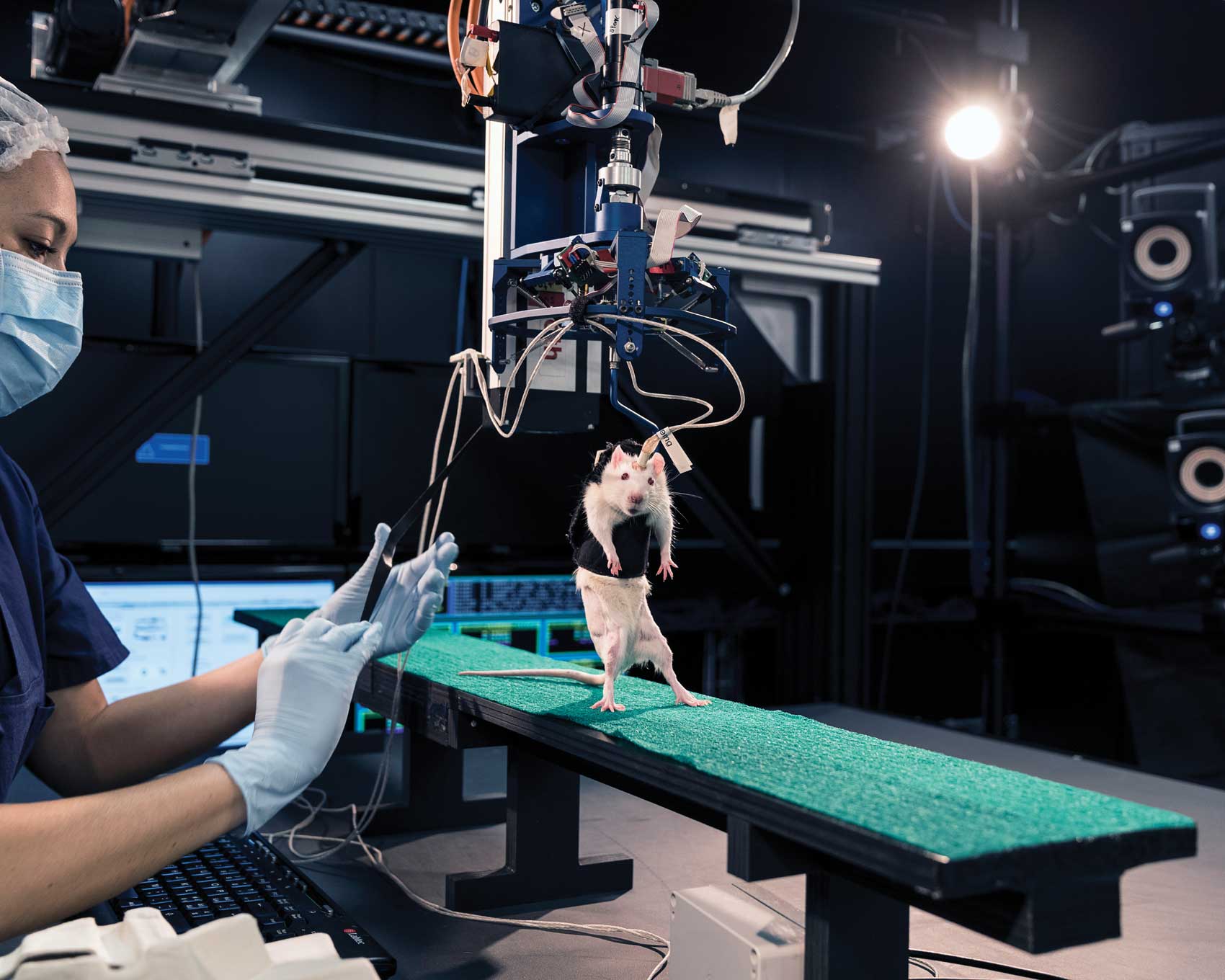

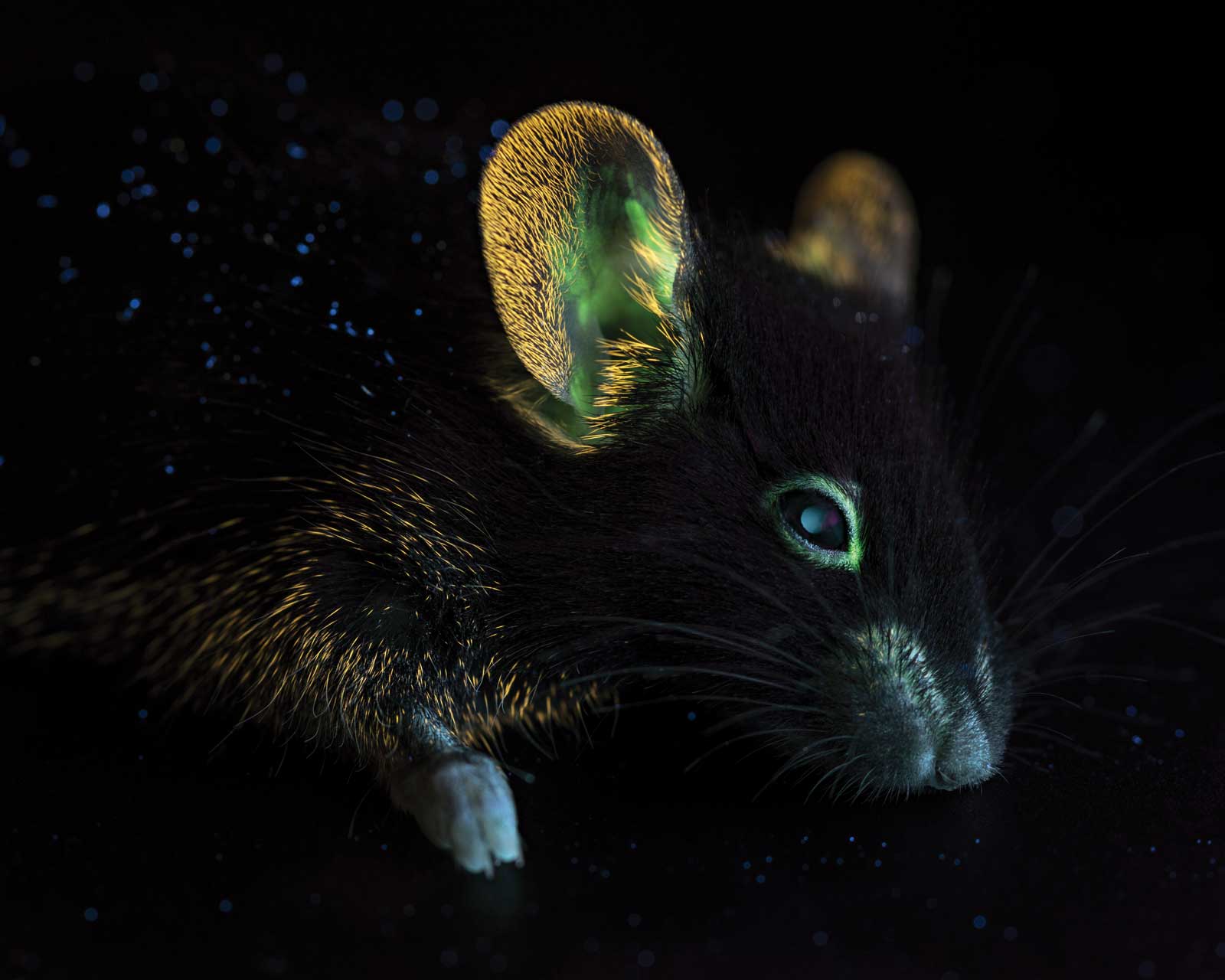

‘Life is a window of vulnerability,’ says Donna J. Haraway in Simians, Cyborgs, and Women. ‘It seems a mistake to close it. The perfection of the fully defended, “victorious” self is a chilling fantasy.’ It’s unusual to catch sight of the intimate moments during which this fantasy plays out on living bodies: when the implant is inserted through a slit in the skin; the point at which the injured lab rat, suspended on hind legs with electrodes and a girdle, looks up, alert. These scenes are both tender and violent. The child’s face, lit with screen-glow, or the X-rayed pacemaker in the chest, or the iodine-swabbed back in the operating theatre, are openly vulnerable. And yet in these photographs the human anatomy is merely one component of the cyborg. It has no special privileges under the camera’s eye. The ubiquitous smartphone receives the same treatment as the rarest implant, which receives the same treatment as a tattooed shoulder blade or a weakening lung. The atmosphere is measured and calm. The mood is . . . there is no mood. Only the edges of blades and syringes, the healed scars and bald expanses of skin imply brutality. Many of the technological augmentations shown here have no medical necessity: they reveal nothing so much as the force of the human desire to be healed, even – especially – when there is nothing really wrong.

All this creates a strong sense of unease. No human subject in this essay can quite look Gafsou in the eye. More often than not, the machines seem more assured than the people: each object is quietly mysterious, expensive, whole. You look at a smooth-edged, brushed-titanium pacemaker, imprinted with a tiny Matisse oak leaf, and you think: I want one. In the even technocracy of H+ there is no outdoors, no family, no dirt, no sense of humour and no such thing as natural light. It’s a shadow-world: strangely familiar, all the same. The basic things – orthodontic braces, flathead screws or cups of coffee – testify to the fact that these augmentations go beyond memory: we have never known a human body without technology. Technology is both oxygen mask and gas chamber. It provides clean drinking water even as it pollutes the reservoir. Our current habits of thought are uneasy with contradiction, which is why the techno-human and the Luddite competitively mythologise themselves. The rest of us live with the contradiction, or, more accurately, we live inside it.

Daisy Hildyard

All images © Matthieu Gafsou / Courtesy Galerie C / Maps