I am the brother of a man who murdered innocent men. His name was Gary Gilmore. After his conviction and sentencing, he campaigned to end his own life, and in January 1977 he was shot to death by a firing squad in Draper, Utah. It was the first execution in America in over a decade.

Many people know this part of the Gary Gilmore story. It was an international news item in 1976 and 1977, and it became the subject of a popular novel and television film. What is less well known, what has never been documented, is the origin of Gary’s violence – the history of my family. It isn’t a comforting story to tell, nor has it been an easy legacy to live with. Over the years, many people have judged me by my brother’s actions as if in coming from a family that yielded a murderer I must be formed by the same causes, the same sins, must by my brother’s actions be responsible for the violence that resulted, and bear the mark of a frightening and shameful heritage. It’s as if there is guilt in the fact of the bloodline itself. Maybe there is.

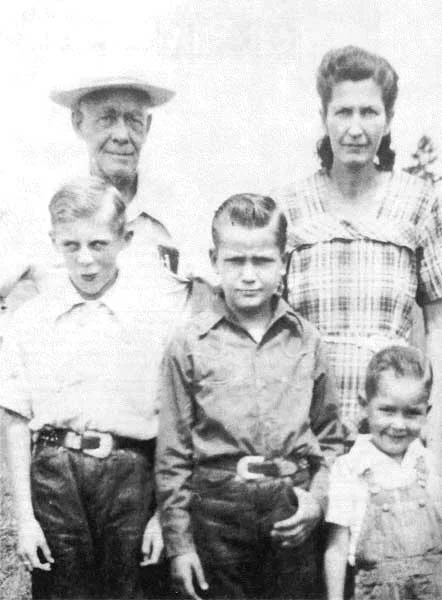

Frank and Bessie Gilmore with (from the left) Frank Jr, Gary and Gaylen, 1949.

Mormon Utah in the early twentieth century was a nation within a nation. The Mormons had been persecuted horribly in the early nineteenth century. They had been driven across the country to the western desert. They had come to believe in violence, not just for protection, but for punishing abuses and betrayals, for vengeance. The early Mormons formed vendetta squads – such as the bloody Sons of Dan – to deal with enemies and traitors.

The Mormons developed a doctrine of blood atonement: if you took life, then you must lose your own (a prescription never applied to the Church’s official assassins). They believed in capital punishment. The bloodier the execution, the better. Atoning for murder required a sacrifice: there should be ritual, blood, witnesses. Mormons favoured death by firing squad or by hanging; these were – and today remain – the only options available to the condemned in Mormon law. Hangings were public. The gallows were placed in meadows or valleys, and Mormons brought their families to watch.

Bessie Gilmore was born Bessie Brown in 1913, the fourth of nine children, in the strict Mormon community of Provo, Utah. She often told us that she remembered being loaded by her father into the family wagon one winter morning, along with her brothers and sisters, and being driven in darkness to a hanging ceremony. She watched the man being led up the stairs to the noose and the executioner. She would not watch the hanging but shut her eyes tight and buried her face in her father’s side. She heard the trapdoor crack open, then a horrible snapping sound as the man’s weight hit the end of the rope’s length and his head was yanked loose from his body. She heard cheers and applause. On moving away from the site, she turned back and saw the man’s body dangling and swaying. Men around her were holding the hands of their children, pointing at the corpse, admonishing their brood to remember the moment and the lesson.

Bessie Brown remembered. The event haunted and terrified her for the rest of her life. She began to hate her own people – or at least the beliefs that would allow them to participate in hanging. When I was a child, and we were living in Portland, Oregon, she anxiously followed the news of impending executions. She wrote letters to the governor, arguing against the death penalty on moral grounds, asking the state to commute the condemned person’s sentence. She asked me, or any of my brothers who might be around, to join her at the dining table and write our own letters to the governor. She explained that these were the only killings we knew were going to occur and the only killings we could prevent.

She called the men who had arranged the public hangings the dead-makers. Mormon law had made it permissible for those watching to enjoy the deaths. She imagined that the executions unleashed the demons of the hanged murderers – demons that flew from the gaping mouths of the men as their necks snapped and their souls departed, and then, once loose, were free to find new victims and haunt the witnesses to the deaths.

When she got older, Bessie began to drink and smoke – two habits forbidden to Mormons – and to flirt with boys. She wore pretty dresses to the Church dances and stayed out all night. One morning, sneaking back home, her father caught her. He called her terrible names and beat her. She ran away; her parents found her living in San Francisco; they dragged her home. A few months later, she ran away again.

Eventually, she ran away for good. One afternoon in Salt Lake City she was visiting some girlfriends at one of the city’s best hotels when she saw a beautiful man stroll into the lobby. Frank Gilmore was dressed in a fine suit and wore spats and carried a cane. She was dazzled. He was the most debonair person she had ever seen. She met him; he charmed her. He was not a Mormon.

My father was born in the late 1890s and grew up among spiritualists, vaudevillians and circus performers. His mother Fay La Foe had worked for many years as a medium, holding seances, telling fortunes, acting as a broker between the living and the dead. It was rumoured that in her younger days she had an affair with an up-and-coming magician, Erich Weiss – later famous as Harry Houdini. One of the family legends was that my father was their offspring, that he was Houdini’s bastard son. According to my mother, my father’s real name was Francis Weiss. She did not know where the name Gilmore came from. It was one of the many surnames he used during his life.

Frank Gilmore was a ladies’ man. He was handsome and intelligent, he dressed splendidly and told captivating stories. He had been a stuntman for the actor Harry Carey and others in the silent film era, and for years worked as a tightwire-walking clown in the Barnum and Bailey Circus under the name of Laffo, until a long fall without a net left him with a severely broken leg and injured back. He claimed that he had been a drinking buddy of Frank James and Buffalo Bill, in the Wild West’s closing days. The only item of self-mythology he never vaunted was his possible relation to Harry Houdini; it was his mother who made that boast, to his irritation. He did not want to be the son of a man whom he would never know.

Frank Gilmore was twenty years older than my mother. He was married, with two children, when she met him. But she wanted to marry him. Frank Gilmore left his wife and in 1939 was married to Bessie Brown in a service conducted by his mother, who had a clergyman’s licence in the Spiritualist Church. Her father was outraged and ashamed.

Whatever enjoyment Frank and Bessie may have had, it did not last long. By the time Frank Jr was born, my father was sullen and drinking heavily, and he and my mother bickered about money, family and religion constantly. My mother tried to keep pace with his drinking, making the nightly rounds of taverns with him as a way of forging a truce, but when she became pregnant again, she stopped drinking.

My father did not want a second child. He claimed the child was not his. He demanded that my mother have an abortion. One night, drunk, he beat her. He beat her again a few nights later. She left with Frank Jr and went to her father’s farm. My father brought her back. They made a peace. Gary was born in 1941. My father neglected his second son; over the years, the disregard would turn to mutual hatred.

Pictures in the family scrapbook show my father with his children. I have only one photograph of him and Gary together. Gary is wearing a sailor’s cap. He has his arms wrapped tightly around my father’s neck, his head bent towards him, a look of broken need on his face. It is heartbreaking to look at this picture – not just for the look on Gary’s face, the look that was the stamp of his future, but also for my father’s expression: pulling away from my brother’s cheek, he is wearing a look of distaste.

When my brother Gaylen was born in the mid forties, my father turned all his love on his new, beautiful brown-eyed son. Gary takes on a harder aspect in the pictures around this time. He was beginning to keep a greater distance from the rest of the family. Six years later, my father turned his love from Gaylen to me. You don’t see Gary in the family pictures after that.

Gary had nightmares. It was always the same dream: he was being beheaded.

In 1953, Gary was arrested for breaking windows. He was sent to a juvenile detention home for ten months, where he saw young men raped and beaten. Two years later, at age fourteen, he was arrested for car theft and sentenced to eighteen months in jail. I was four years old.

When I was growing up I did not feel accepted by, or close to, my brothers. By the time I was four or five, they had begun to find life and adventure outside the home. Frank, Gary and Gaylen signified the teenage rebellion of the fifties for me. They wore their hair in greasy pompadours and played Elvis Presley and Fats Domino records. They dressed in scarred motorcycle jackets and brutal boots. They smoked cigarettes, drank booze and cough syrup, skipped – and quit – school, and spent their evenings hanging out with girls in tight sweaters, racing souped-up cars along country roads outside Portland, or taking part in gang rumbles. My brothers looked for a forbidden life – the life they had seen exemplified in the crime lore of gangsters and killers. They studied the legends of violence. They knew the stories of John Dillinger, Bonnie and Clyde, and Leopold and Loeb; mulled over the meanings of the lives and executions of Barbara Graham, Bruno Hauptmann, Sacco and Vanzetti, the Rosenbergs; thrilled to the pleading of criminal lawyers like Clarence Darrow and Jerry Giesler. They brought home books about condemned men and women, and read them avidly.

I remember loving my brothers fiercely, wanting to be a part of their late-night activities and to share in their laughter and friendship. I also remember being frightened of them. They looked deadly, beyond love, destined to hurt the world around them.

One hot summer afternoon, I was sitting in the living room watching television when my brother Gaylen walked through the front door. He was bare chested and covered with blood. He had tried to join a local gang. For the initiation, the gang lord had stripped him and tied him up, then shot him repeatedly with a pellet rifle. Gaylen sat in a chair at the kitchen table as my mother washed the blood from him and picked the pellets from his arms and chest. She cried and talked about calling the police, but Gaylen made her promise that she wouldn’t.

Mikal Gilmore, 1959

Gary came home from reform school for a brief Christmas visit. On Christmas night I was sitting in my room, playing with the day’s haul of presents, when Gary wandered in. ‘Hey Mike, how you doing?’ he asked, taking a seat on my bed. ‘Think I’ll just join you while I have a little Christmas cheer.’ He had a six-pack of beer with him and was speaking in a bleary drawl. ‘Look partner, I want to have a talk with you.’ I think it was the first companionable statement he ever made to me. I never expected the intimacy that followed and could not really fathom it at such a young age. Sitting on the end of my bed, sipping at his Christmas beer, Gary described a harsh, private world and told me horrible, transfixing stories: about the boys he knew in the detention halls, reform schools and county farms where he now spent most of his time; about the bad boys who had taught him the merciless codes of his new life; and about the soft boys who did not have what it took to survive that life. He said he had shared a cell with one of the soft boys, who cried at night, wanting to disappear into nothing, while Gary held him in his arms until the boy finally fell into sleep, sobbing.

Then Gary gave me some advice. ‘You have to learn to be hard. You have to learn to take things and feel nothing about them: no pain, no anger, nothing. And you have to realize, if anybody wants to beat you up, even if they want to hold you down and kick you, you have to let them. You can’t fight back. You shouldn’t fight back. Just lie down in front of them and let them beat you, let them kick you. Lie there and let them do it. It is the only way you will survive. If you don’t give in to them, they will kill you.’

He set aside his beer and cupped my face in his hands. ‘You have to remember this, Mike,’ he said. ‘Promise me. Promise me you’ll be a man. Promise me you’ll let them beat you.’ We sat there on that winter night, staring at each other, my face in his hands, and as Gary asked me to promise to take my beatings, his bloodshot eyes began to cry. It was the first time I had seen him shed tears.

I promised: Yes, I’ll let them kick me. But I was afraid – afraid of betraying Gary’s plea.

My father had taken his love from everybody else in the family and came to favour only me with it. This was another reason I felt apart from my brothers and I have never been comfortable admitting it. I was held up to them as the example of worth and goodness that they were not. Before I was born, Gaylen had been the favoured one. After I arrived, my father shunned Gaylen, made fun of him, called him fat, hit him, accused him of heading towards Gary’s criminal life – which he accordingly did. My father never brutalized me, as he had brutalized Gary and Gaylen. Maybe he saw me as his last chance at successful love.

I remember my father finishing one tirade by taking Gaylen’s pearl-handled, nickel-plated toy revolver, one of Gaylen’s favourite possessions, and giving it to me. A day or two later, after my father left town on business, Gaylen dragged all my toys into the side yard and locked me in the house. I watched out of the dining-room window as he smashed toy after toy with an axe. He tossed the shattered heap of plastic in the trash can. When he came back in, he was crying. ‘Someday,’ he said in a voice thick with pain, ‘he’ll hate you too.’

Then there was the incident on Christmas Day.

I don’t remember how it started, but my father and Gary became embroiled in an ugly confrontation. Each tested the other’s toughness. Then they threatened to kill each other. My mother pleaded with them to stop, but the moment was too tense. Gaylen stepped in and asked my father to leave Gary alone. My father – already an old man, but still amazingly strong – made a fist and punched Gaylen in the stomach. I have never forgotten the awfulness of that blow. Gaylen doubled over in pain, and Gary went over to help him. My father grabbed me and said that we were leaving and would spend Christmas in a hotel. I did not want to go, and I said so. ‘Don’t you turn against me too,’ he said, and the look of rage and hurt on his face was enough to make me go with him. I was afraid of what he might do to us all if I stayed.

My mother begged my father to remain, to apologize to Gaylen and Gary and try to repair the Christmas, or at least to let me spend the holiday with my brothers. My father would hear none of it. As he and I were in the car, pulling out of the driveway, I looked up at my mother and brothers, who were gathered on the porch, watching us leave. I could tell from the way my brothers were looking at me that they would never forgive me, would never let me into their fraternity.

I felt like a traitor. I wanted to join my brothers – to be standing with them on the porch, watching as the source of their hurt left them – but I knew I never could. I was eight, maybe nine, years old.

The Gilmore brothers, 1959

In 1960, my family moved from the semi-rural, semi-industrial outskirts of Portland to an upper-middle-class area nearby, known as Milwaukie. My father had settled down, as much as he knew how to. He had become a self-styled publishing entrepreneur: he compiled the numerous residential and business building codes for the areas of Seattle, Tacoma and Portland, and published them in seasonal manuals in which he sold advertising spaces to local architects and contractors. It proved a lucrative business. We bought a big four-bedroom house with a teardrop shaped driveway, perched at the top of a hill that afforded a remarkable view of the entire stretch of the Willamette Valley. On clear days, you could view the fast-changing, oddly lopsided skyline of downtown Portland.

My mother saw the relocation as a new start. This was the home she had always wanted, she said, and she set about landscaping the yard with elaborately patterned flower gardens and filling the house with fine furniture imported from Europe and Japan. I think she hoped that a new, better home would rehabilitate the family, give my wayward brothers new pride and win back my father’s faith and support for his sons.

But Gary was drinking and popping pills. He began hanging out with the friends he had met in jail. He brought home guns. But he proved more a fearless crook than a clever one; he was arrested often, and each new sentence stretched longer than the one before. He had lived most of his adolescence and young adulthood in Oregon’s city and county jails and had acquired a reputation as a hard-ass – somebody the other prisoners were not likely to go up against and the jailers would watch warily. He spent over half his jail time in isolation, for defying the institution’s rules or for provoking or hitting guards. Many times he found himself in the jail hospital, following beatings by guards. He escaped twice – once by jumping from a second-storey window at a pre-trial hearing. It was that escape, I think, that produced his longest free time; he was gone for nearly two years, travelling around the country. One day, we got a call from Texas – the state where Gary had been born. He needed money; he had met a woman he wanted to marry and they were going to have a baby. Reluctantly, my father sent the money. That was the last we ever heard of wife and baby.

Gaylen had his own litany of misdeeds. He was suspended from the local junior high and high schools, and eventually expelled. He stole cars and committed thefts and he drank a good deal more than Gary. By the age of sixteen, Gaylen was a full-fledged alcoholic. In time, he developed his own criminal speciality – forging signatures and writing bad cheques – and, like Gary, spent much of his time in local jails or in flight, skipping bail and violating probation or parole. He joined the navy. He lasted six weeks. After he had gone AWOL five times, the base commanders concluded that Gaylen did not have a military career ahead of him and shipped him back home with an honourable discharge.

If my family sounds like white trash – as many have asserted – well, perhaps it was. Yet we were anomalous white trash. Gary was an artist: I don’t mean simply that he could draw well, or that he had pretensions, but that he could draw and paint with remarkable clarity and empathy. The best of his work had the high-lonesome, evocative power of Andrew Wyeth’s or Edward Hopper’s, though it was more openly haunted and death-obsessed. Gaylen read Poe, Rilke, Nietzsche, Kant, and memorized pages from Shakespeare, Thomas Wolfe and Edwin Arlington Robinson. He also wrote poetry, and it was startling. Like Gary’s art, it spoke about being on the outside of life, heading for a self-willed inferno.

Where did this odd mix of raw talent, uncanny intelligence and wasteful ambition come from? Why did their gifts mean so little to my brothers? Why did they prefer a life of crime over a life in art?

I tried to talk to my brothers about their artistic interests, but they didn’t want to talk. One afternoon, when Gary and I were sitting around the house, I tried to get him – for the umpteenth time – to show me some basics about drawing. He was drinking cough syrup and laughed in a polite but firm way that announced: No dice. I tried to crack Gary’s indifference, to tell him I thought he could be a successful artist if he wanted to. Why didn’t he make art his life – or at least his vocation? He chased his cough syrup with a swig of beer, then looked at me and smiled. ‘You want to learn how to be an artist?’ he said. ‘Then learn how to eat pussy. Learn that, and it’s the only art you’ll ever need to learn.’

Gary and Gaylen weren’t at home much. I came to know them mainly through their reputations, through the endless parade of grim policemen who came to the door trying to find them, and through the faces and accusations of bail bondsmen and lawyers who arrived looking sympathetic and left disgusted. I knew them through many hours spent in waiting rooms at city and county jails, where my mother went to visit them, and through the numerous times I accompanied her after midnight to the local police station on Milwaukie’s Main Street to bail out another drunken son.

I remember being called into the principal’s office while still in grammar school, and being warned that the school would never tolerate my acting as my brothers did; I was told to watch myself, that my brothers had already used years of the school district’s good faith and leniency, and that if I was going to be like them, there were other schools I could be sent to. I came to be seen as an extension of my brothers’ reputations. Once, I was waiting for a bus in the centre of the small town when a cop pulled over. ‘You’re one of the Gilmore boys, aren’t you? I hope you don’t end up like those two. I’ve seen enough shitheads from your family.’ I was walking down the local main highway when a car pulled over and a gang of older teenage boys piled out, surrounding me. ‘Are you Gaylen Gilmore’s brother?’ one of them asked. They shoved me into the car, drove me a few blocks to a deserted lot and took turns punching me in the face. I remembered Gary’s advice – ‘You can’t fight back; you shouldn’t fight back’ – and I let them beat me until they were tired. Then they spat on me, got back in their car and left.

I cried all the way back home, and I hated the world. I hated the small town I lived in, its ugly, mean people. For the first time in my life I hated my brothers. I felt that my future would be governed by them, that I would be destined to follow their lives whether I wanted to or not, that I would never know any relief from shame and pain and disappointment. I felt a deep impulse to violence: I wanted to rip the faces off the boys who had beat me up. ‘I want to kill them,’ I told myself, ‘I want to kill them’ – and as I realized what it was I was saying, and why I was feeling that way, I only hated my world, and my brothers, more.

I’ve come to understand better why my brothers didn’t seem to mind spending so much time in jail: it was preferable to being at home. My parents fought bitterly and often. In the worst fights my father would taunt or insult my mother until, driven by his sure-handed meanness, she would attack him physically. Many times I threw myself between them, trying to stop the fighting, begging them to forgive and love one another (my brothers, when they were home, refused to interfere in these fights; they said the battles had been going on for too many years, and there was no longer any point in becoming involved). Sometimes I succeeded in calming my parents, but the wounds were deep, and my mother would usually end up standing in front of my father, her face contorted in humiliation and fury, swearing that she would knife him in the throat during his sleep for all the pain he had made her feel. My father would fold out the sofa in the living room and surround it with a fortress of chairs, so he could hear my mother tripping over them if she came to kill him. He would lie down on the sofa to sleep, and he would keep me next to him. Many nights I would lie there, next to my sleeping father, waiting for the sound of footsteps, the creak of floorboards, the glint of the knife. I would lie there watching the darkness. I would not fall asleep until dawn.

Sometimes, the fights were about me: who would have custody if they divorced or should I stay with my mother or go with my father when he made his trips between Portland and Seattle. My parents insisted that I choose between them. I felt awful no matter what choice I made. This is the way I learned how to love.

The time I spent with my father in Seattle was more peaceful than the time I spent at home in Portland. My father was busy and left me to myself. He didn’t care if I stayed home from school for days on end. Because my brothers did not play with me much as a child, I was accustomed to keeping to myself. I filled the day by walking to the zoo, or catching a bus downtown, where I’d hang out in bookstores and movie theatres, or spend hours exploring abandoned Victorian houses in the Queen Anne district.

In the evenings, I sat in the apartment, reading the fantasy fiction of Edgar Rice Burroughs and Jules Verne, the horror stories of Edgar Allan Poe, the epic comic-book tales of Carl Barks or the EC crime and horror tales. Then I would huddle close to my father when he arrived home, and we would watch television together until late at night. We liked the westerns and police dramas. We would watch Maverick, Have Gun Will Travel, Dragnet or The Untouchables, one evening after another, far away from the tumult of the home back in Oregon.

It was during one of these stays in Seattle, in the early months of 1962, that I learned that my father had lung cancer and would die within months. He never knew what was coming. One day he had been old – in his late sixties – but still strong and active; the next he was horribly tired and sick, confined to the bed where he spent the last few months of his life coughing sputum into a bowl. I remember the smell of it, because I lived in the same room with it until the day my father died. It was sickly sweet, like a spoiled flower. I was surprised that death could be fragrant.

My mother was grief-stricken. She tried to show him tenderness and care, but the years of abuse had taken their toll. As my father slept in the next room, my mother talked about how he had hurt and betrayed her and how she had come to hate him – she hated him more now that he was going to leave her alone with the family, with little money. I had never heard her sound more bitter. I left the room and walked past my father’s room and looked in on him. He was sitting on the side of his bed, holding his head in his hands, and when he looked up at me, I saw agony on his face. I went back to my mother and told her that he had overheard what she had said. ‘Good,’ she replied. ‘I wanted him to hear.’ Later that night, I found my parents sitting at the kitchen table, holding hands, talking softly. My father was crying, and my mother was petting his hand. I had never seen my parents hold each other’s hands before.

Gary stole a car in Portland and drove it up to Seattle to see my father; I think he was hoping for a last chance at reconciliation. On the drive back, Gary was arrested as he crossed the Washington–Oregon border. He was sentenced to a year and a half in the county jail.

Frank Gilmore, Sr died on 30 June 1962. Gary was in Portland’s Rocky Butte Jail, and the authorities denied his request to attend the funeral. He tore his cell apart; he smashed a light bulb and slashed his wrists. He was placed in ‘the hole’ – solitary confinement – on the day of my father’s funeral. Gary was twenty-one. I was eleven.

I was surprised at how hard my mother and brothers took my father’s death. I was surprised they loved him enough to cry at all. Or maybe they were crying for the love he had so long withheld, and the reconciliation that would be forever denied them. I was the only one who didn’t cry. I don’t know why, but I never cried over my father’s death – not then, and not now.

Frank Gilmore had not planned for dying. He had not made adequate preparations for his family: there was no will and no money. He left a large house that was still not paid for, and a business that neither my mother nor brothers knew how to operate, though we all tried our hands at it. It wasn’t clear who held the copyright on my father’s publications, and within a few months, competitors moved in and claimed that he had promised the business to them. Eventually my mother lost control over the publishing; when she did, the family was without solvency and without a financial future. To save the house, and to keep me in school, my mother took a series of menial jobs – working as a crew leader during the summer for children picking berries and beans in local fields, and eventually settling into a job as a waiter’s assistant at a local restaurant in downtown Milwaukie. She worked long hours and developed a form of arthritis that proved progressively crippling. She dreamed of the day when she would receive social security payments that were large enough to allow her to quit her job. In time, the work and expenses proved too much. My mother lost her job at the restaurant when her hands and legs became too stiff and enfeebled for her to work. After that, there was never much money. For a while we went on welfare. My mother felt humiliated.

With my father’s death Gary’s crimes became more desperate, more violent. He talked a friend into helping him commit armed robbery. Gary grabbed the victim’s wallet while the friend held a club; he was arrested a short time later, tried and found guilty. The day of his sentencing, during an afternoon when my mother had to work, he called me from the Clackamas County Courthouse. ‘How you doing partner? I just wanted to let you and mom know: I got sentenced to fifteen years.’

I was stunned. ‘Gary, what can I do for you?’ I asked. I think it came out wrong, as if I was saying: I’m busy; what do you want?

‘I… I didn’t really want anything,’ Gary said, his voice broken. ‘I just wanted to hear your voice. I just wanted to say goodbye. You know, I won’t be seeing you for a few years. Take care of yourself.’ We hadn’t shared anything so intimate since that Christmas night, many years before.

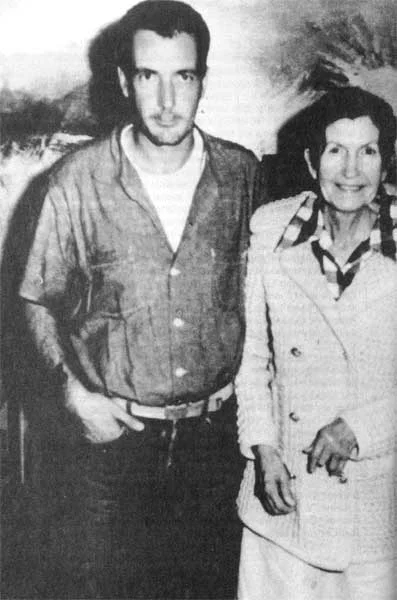

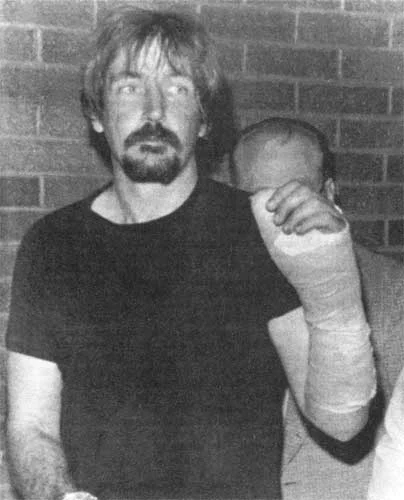

Gary Gilmore with his mother, Bessie Gilmore

My brother Frank had converted to the Jehovah’s Witnesses; he’d had enough of both Catholic and Mormon theology. In 1966, he was drafted, but refused to learn how to fire a rifle in basic training; his Church would not allow its members to carry or use arms in the nation’s name. Frank was court-martialed and served three years at Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary. One brother jailed for his tendency to violence; another for his refusal to participate in sanctioned violence.

Gaylen got into progressively worse scrapes. One night, my mother and I were sitting in the kitchen when a car pulled into the driveway and several men piled out. My mother quickly locked the door and dragged me up the stairs into my father’s old office. From downstairs, we could hear the men kicking and pounding on the door. ‘If you make us come in there to find you, Gilmore, we’re going to kill you.’ My mother did something I had never known her to do before: she called the police. The pounding and threats continued for several minutes until the sound of a police siren’s wail began to make its way up the hill. The men jumped in their car and were gone. A few days later, when Gaylen returned home, my mother told him about the incident. He sat quietly for a while, then asked my mother if she could lend him a hundred dollars; there was something he needed to do. She opened her purse, gave him the money, and Gaylen walked out of the door without saying a word. The next time we heard from him, he was in Salt Lake City, visiting an old friend. He had no plans to return home, he said. Then, a few months later, we heard he was in the hospital, in critical condition. His friend had found him in bed with his wife and stabbed him.

Gaylen recovered and went to Chicago to visit some friends. In 1970 he returned home. He had changed. He was pinched and emaciated. His speech was broken. He still drank too much and was taking painkillers. He seemed to have lost much of his wit and intelligence. He knocked on my door at two in the morning, in a drunken stupor, and stumbled in and dropped on the sofa, talking incoherently. I put a blanket on him and sat with him until he passed out.

Gaylen persuaded his girlfriend from Chicago to join him in Portland. In November 1971, they were married. Two weeks after the wedding, he woke up one night in severe pain; the knife wounds in his stomach and bowel had reopened. He went into the hospital and a few nights later at three in the morning, his wife called me. Gaylen was dead. He was twenty-six years old.

The next morning, my brother Frank and I visited Gary at Oregon State Penitentiary to tell him the news. As he entered the visitors’ room, he looked unusually old and tired for a man of thirty. He knew that something was wrong.

‘We have bad news for you, Gary,’ Frank began.

The warden at Oregon State allowed Gary to attend the funeral. It was the first time the family had gathered together in nine years. It was also the last time.

I didn’t have much talent for crime (neither did my brothers, to tell the truth), but I also didn’t have much appetite for it. I had seen what my brothers’ lives had brought them. For years, my mother had told me that I was the family’s last hope for redemption. ‘I want one son to turn out right, one son I don’t have to end up visiting in jail, one son I don’t have to watch in court as his life is sentenced away, piece by piece.’ After my father’s death, she drew me closer to her and her religion, and when I was twelve, I was baptized a Mormon. For many years, the Church’s beliefs helped to provide me with a moral centre and a hope for deliverance that I had not known before.

I think culture and history helped to save me. I was born in 1951, and although I remember well the youthful explosion of the 1950s, I was too young to experience it the way my brothers did. The music of Elvis Presley and others had represented and expressed my brothers’ rebellion: it was hard edged, with no apparent ideology. The music was a part of my childhood, but by the early sixties the spirit of the music had been spent.

Then, on 9 February 1964 (my thirteenth birthday, and the day I joined the Mormon priesthood), the Beatles made their first appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show. My life would never be the same. The Beatles meant a change, they promised a world that my parents and brothers could not offer. In fact, I liked the Beatles in part because they seemed such a departure from the world of my brothers, and because my brothers couldn’t abide them.

The rock culture and youth politics of the sixties allowed their adherents to act out a kind of ritualized criminality: we could use drugs, defy authority, or contemplate violent or destructive acts of revolt, we told ourselves, because we had a reason to. The music aimed to foment a sense of cultural community, and for somebody who had felt as disenfranchised by his family as I did, rock and roll offered not just a sense of belonging but empowered me with new ideals. I began to find rock’s morality preferable to the Mormon ethos, which seemed rigid and severe. One Sunday in the summer of 1967, a member of the local bishopric – a man I admired, and had once regarded as something of a father figure – drove over to our house and asked me to step outside for a talk. He told me that he and other church leaders had grown concerned about my changed appearance – the new length of my hair and my style of dressing – and felt it was an unwelcome influence on other young Mormons. If I did not reject the new youth culture, I would no longer be welcome in church.

On that day a line was drawn. I knew that rock and roll had provided me with a new creed and a sense of courage. I believed I was taking part in a rebellion that mattered – or at least counted for more than my brothers’ rebellions. In the music of the Rolling Stones or Doors or Velvet Underground, I could participate in darkness without submitting to it, which is something Gary and Gaylen had been unable to do. I remember their disdain when I tried to explain to them why Bob Dylan was good, why he mattered. It felt great to belong to a different world from them.

And I did: my father and Gaylen were dead; Gary was in prison and Frank was broken. I thought of my family as a cursed outfit, plain and simple, and I believed that the only way to escape its debts and legacies was to leave it. In 1969 I graduated from high school – the only member of my family to do so. The next day, I moved out of the house in Milwaukie and, with some friends, moved into an apartment near Portland State University, in downtown Portland. A short time later, encumbered by overdue property taxes, my mother gave up the nice home on the hill that she had struggled to hold on to. She and my brother Frank bought a small trailer, and settled into a trailer camp.

Gary and I exchanged letters, but whole worlds separated us. In Oregon inmates weren’t allowed visitors under the age of eighteen. I felt too guilty to write to Gary about what I was doing in school or about friends and pastimes, because to Gary these existed on the ‘outside’. After Gaylen’s death, Gary seemed to change. He had lost two members of his family without the opportunity for final reconciliation, and he wanted desperately to be free. In his letters, he began to express more concern for me, more curiosity about what I was doing, who my friends were. He was trying to be my brother. But I told myself I didn’t have time for the long trek down to Salem, Oregon, to visit him. I think I was trying to forget him, trying to leave him and our past life behind.

But Gary didn’t want to be forgotten.

In the fall of 1972, Gary was granted a ‘school release’ to attend a community college in Eugene, Oregon, and study art, on the condition that he return to a dorm facility every evening and never leave the Eugene area without the consent of his counsellors. Our family saw it as a turning point.

But on the morning of his release, Gary showed up at my door, a six-pack of beer in his hand. He explained that he wanted to visit friends and family in Portland. ‘I’ll go back before the night,’ he said. ‘I can still register tomorrow without getting in any trouble.’

The next afternoon, he showed up again. He was wearing a long black raincoat and a porkpie hat. With his half-grown goatee he looked like a hick hipster. He had a red glare about his eyes. He had not returned to Eugene as he said he would. For his failure to do so he could not only lose his scholarship but be sentenced to additional jail time.

‘Gary, what are you doing here?’

He skirted the question. ‘Let’s get lunch some place. Know any good places?’ I said that there was a restaurant within walking distance, but Gary didn’t want to be seen on the streets. He wanted to go by taxi. My anger began to turn to dread. We ended up at a topless bar. As Gary studied the girl on stage, he seemed to be in a trance. I asked him why he wasn’t going to school.

He was silent for a long time and stared at the table. When he spoke, it was with his slow, countrified drawl. ‘I’m not cut out for school. Man, they can’t teach me anything about art that I don’t already know. Besides, there are more important things.’ He leaned towards me and locked his stare into mine. ‘A friend of mine from the joint is being brought up to the dental school here next week. A couple of guards are bringing him up and I want to go see him. Uh, I need a gun. Can you help me?’

I told him he was throwing away his life.

He narrowed his eyes. ‘It’s a matter of dignity,’ he said. Gary stared at me for a long time without expression. He fidgeted with a book of matches. ‘I’d do it for my brother,’ he said.

I saw him only two more times that month. He visited me while I had a girlfriend over and asked me to play Johnny Cash records for him. He was sober and charming. When we were alone, I tried to prod him about his plans. ‘Let’s just say they’ve changed,’ he said. ‘Don’t you worry about it. The less you know, the better off you are.’

A few days later I came out of a class at Portland State and Gary was waiting outside. He had borrowed a car and wanted me to meet some friends. We drove out, Gary drinking beer and conversing in a friendly manner. At his friends’ house, Gary showed me a collection of his drawings and paintings: drawings of children, studies of ballet dancers and bruised boxers, an occasional depiction of violent death. ‘Here,’ he said, ‘take what you want.’ To him, pictures were drawn then given away.

His friends enjoyed luxury that he had never known. While showing me the indoor swimming pool, Gary opened his jacket, took out a pistol and handed it to me, handle first. ‘Think you could ever use one of these?’ he asked in his best Gary Cooper fashion.

I felt awkward and vulnerable: it was the first time I had ever held a gun. I kept the barrel pointed towards the pool and lifted my finger from the trigger. He took the gun and returned it to his jacket pocket. ‘C’mon,’ he said. ‘I’ll drive you home.’ We drove back in silence. He seemed angry.

Two nights later I watched a news report of his arrest for armed robbery. My mother and I were unable to visit him in jail, but we attended his trial. Handcuffed and on the verge of tears, Gary acted as his own defence and pleaded for a reprieve. ‘I have done a lot of time and I don’t think it would do me good to do any more,’ he told the judge. ‘I have been locked up for the last nine and one half calendar years consecutively, and I have had about two and a half years of freedom since I was fourteen years old. I have always gotten time and have always done it, never been paroled, only had one probation. I have never had a break from the law and I have come to think that justice is kind of harsh and I have never asked for a break until now.’

The judge sentenced Gary to an additional nine years. The next time I saw him was six days before his execution.

In the summer of 1976, I was working at a record store in downtown Portland, making enough money to pay my rent and bills. I was also writing freelance journalism and criticism, and had sold my first reviews and articles to national publications, including Rolling Stone.

On the evening of 30 July, having passed up a chance to go drinking with some friends, I headed home. The Wild Bunch, Peckinpah’s genuflection to violence and honour, was on television, and as I settled back on the couch to watch it, I picked up the late edition of The Oregonian. I almost passed over a page-two item headlined oregon man held in utah slayings, but then something clicked inside me, and I began to read it. ‘Gary Mark Gilmore, 35, was charged with the murders of two young clerks during the hold-up of a service station and a motel.’ I read on, dazed, about how Gary had been arrested for killing Max Jensen and Ben Bushnell on consecutive nights. Both men were Mormons, about the same age as I, and both left wives and children behind.

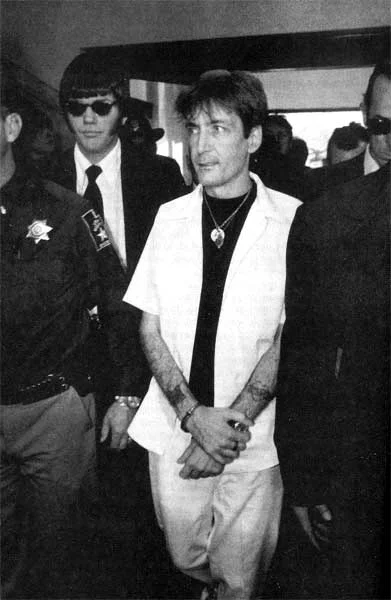

Gary Gilmore at his murder arraignment, July 1976

I dropped the paper to the floor. I sat on the couch the rest of the night, alternately staring at The Wild Bunch and re-reading the sketchy account. I felt shocks of rage, remorse and guilt – as if I were partly responsible for the deaths. I had been part of an uninterested world that had shut Gary away. I had wanted to believe that Gary’s life and mine were not entwined, that what had shaped him had not shaped me.

It had been a long time since I had written or visited Gary. After his re-sentencing in 1972, I heard news of him from my mother. In January 1975, Gary was sent to the federal penitentiary in Marion, Illinois. After his transfer, we exchanged a few perfunctory letters. In early April 1976, I learned of the Oregon State Parole Board’s decision to parole Gary from Marion to Provo, Utah, rather than transfer him back to Oregon. The transaction had been arranged between the parole board, Brenda Nicol (our cousin) and her father, our uncle Vernon Damico, who lived in Provo. I remember thinking that Gary’s being paroled into the heart of one of Utah’s most devout and severe Mormon communities was not a great idea.

Between his release and those fateful nights in July, Gary held a job at Uncle Vernon’s shoe store, and he met and fell in love with Nicole Barrett, a beautiful young woman with two children. But Gary was unable to deny some old, less wholesome appetites. Almost immediately after his release, he started drinking heavily and taking Fiorinal, a muscle and headache medication that, in sustained doses, can cause severe mood swings and sexual dysfunction. Gary apparently experienced both reactions. He became more violent. Sometimes he got rough with Nicole over failed sex, or over what he saw as her flirtations. He picked fights with other men, hitting them from behind, threatening to cave in their faces with a tyre iron that he twirled as handily as a baton. He lost his job and abused his Utah relatives. He walked into stores and walked out again with whatever he wanted under his arm, glaring at the cashiers, challenging them to try to stop him. He brought guns home, and sitting on the back porch would fire them at trees, fences, the sky. ‘Hit the sun,’ he told Nicole. ‘See if you can make it sink.’ Then he hit Nicole with his fist one too many times, and she moved out.

Gary wanted her back. He told a friend that he thought he might kill her.

On a hot night in late July, Gary drove over to Nicole’s mother’s house and persuaded Nicole’s little sister, April, to ride with him in his white pickup truck. He wanted her to join him in looking for her sister. They drove for hours, listening to the radio, talking aimlessly, until Gary pulled up by a service station in the small town of Orem. He told April to wait in the truck. He walked into the station, where twenty-six-year-old attendant Max Jensen was working alone. There were no other cars there. Gary pulled a .22 automatic from his jacket and told Jensen to empty the cash from his pockets. He took Jensen’s coin changer and led the young attendant around the back of the station and forced him to lie down on the bathroom floor. He told Jensen to place his hands under his stomach and press his face to the ground. Jensen complied and offered Gary a smile. Gary pointed the gun at the base of Jensen’s skull. ‘This one is for me,’ Gary said, and he pulled the trigger. And then: ‘This one is for Nicole,’ and he pulled the trigger again.

The next night, Gary walked into the office of a motel just a few doors away from his uncle Vernon’s house in Provo. He ordered the man behind the counter, Ben Bushnell, to lie down on the floor, and then he shot him in the back of the head. He walked out with the motel’s cashbox under his arm and tried to stuff the pistol under a bush. But it discharged, blowing a hole in his thumb.

Gary decided to get out of town. First he had to take care of his thumb. He drove to the house of a friend named Craig and telephoned his cousin. A witness had recognized Gary leaving the site of the second murder, and the police had been in touch with Brenda. She had the police on one line, Gary on another. She tried to stall Gary until the police could set up a roadblock. After they finished speaking, Gary got into his truck and headed for the local airport. A few miles down the road, he was surrounded by police cars and a SWAT team. He was arrested for Bushnell’s murder and confessed to the murder of Max Jensen.

Gary’s trial began some months later. The verdict was never in question. Gary didn’t help himself when he refused to allow his attorneys to call Nicole as a defence witness. Gary and Nicole had been reconciled; she felt bad for him and visited him in jail every day for hours. Gary also didn’t help his case by staring menacingly at the jury members or by offering belligerent testimony on his own behalf. He was found guilty. My mother called me on the night of Gary’s sentencing, 7 October, to tell me that he had received the death penalty. He told the judge he would prefer being shot to being hanged.

On 8 November I heard that Gary had waived all rights of appeal and review. He wanted to be executed. Fourth District Judge J. Robert Bullock had complied, setting the date of execution for Monday 15 November. Gary’s attorney filed for a stay of execution – against his protests – and the Utah Supreme Court granted one.

I decided to confront Gary about his decision. The next day I called Draper Prison, where he was being held. Our first exchanges were polite and tentative. Gary became impatient. ‘Something on your mind?’

I asked if he was serious about requesting execution.

‘What do you think?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘That’s right. You don’t. You never knew me.’ Gary had thrown down a barrier I couldn’t leap over. I was lost for a reply. ‘Look,’ he continued, in a softer tone, ‘I’m not trying to be mean to you, but this thing’s going to happen one way or the other; there’s nothing you can do to stop it and I don’t particularly want you to like me for it. It’ll be easier for me if you don’t. It seems the only time we ever talk to each other is around the time of somebody’s death. Now it’s mine.’

I felt helpless. I asked him to consider our mother.

‘Well, I want to see Mother before all this goes down,’ Gary said. ‘I want to see all of you. Maybe that will make it easier. But I don’t want you or anybody else to interfere. It’s my affair. I don’t want to spend the rest of my life on trial or in prison. I’ve lost my freedom. I lost it a long time ago. I don’t want you to think I’m some “sensitive” artist because I drew pictures or wrote poems. I killed – in cold blood.’ A guard told Gary that his time was up. I asked him to tell his new attorney, Dennis Boaz, to call me. Boaz phoned that night. He said that he supported Gary’s right to die and that on the following day, 10 November, he and Gary would appear before the Utah Supreme Court and ask them to lift the stay. I asked Boaz to call me as soon as the court made its decision. He promised to call me by four o’clock the next day. His closing line stayed with me. ‘Is it OK if I call you collect? I’m a poor man.’

He didn’t call. I learned of his and Gary’s successful appearance before the court on the network news, which showed clips of my brother being led from the courtroom in shackles, with his wary, piercing stare. Overnight, the most painful and private part of my family’s history, a past that I had tried for years to escape, was everywhere. Gary was on the national news nearly every evening of the week; he was on the front page of every newspaper I saw; he was staring out at me from the cover of Newsweek. Inside the magazine, I found pictures from my family’s photo albums. There was a picture from a distant Christmas with my father, Gary, Gaylen and me, standing in a line. Nobody in the picture looked happy.

Utah governor Calvin Rampton ordered a stay of execution, referring the matter to the state board of pardons and earning the epithet of ‘moral coward’ from Gary. I received a call on the night of his order from Anthony Amsterdam of Stanford Law School, a well-regarded opponent of the death penalty and a member of the bar of the United States Supreme Court. He outlined a possible course of action for the family: a family member could retain counsel to seek a stay from the US Supreme Court, the duration of which would be determined by the Court’s willingness to review the case and the subsequent decision of that review. This meant that Gary would be entitled to a new trial. I passed the information on to my mother, who also spoke with Amsterdam. We agreed to retain him pending the pardons board decision. On Tuesday morning, 16 November, the day after Gary’s scheduled execution, Amsterdam called me with the news that Gary and Nicole had attempted suicide with an overdose of sedatives.

On 30 November the pardons board decided to allow the execution to go forward. On 3 December the US Supreme Court granted a stay of execution. Our calls to the prison were turned away. Gary issued an open letter asking my mother to ‘butt out’. During this time neither Gary nor his legal representatives attempted to contact any members of the immediate family.

On the morning of 13 December, the Supreme Court lifted its stay, declaring that Gary had made a ‘knowing and intelligent waiver of his rights’. The next day Judge Bullock reset the execution for 17 January. Gary was confined to a ‘strip cell’ and denied visits, even from family members.

By Christmas I told myself and anyone who asked that I didn’t care about what might happen. I spent the holidays drunk or drugged. My girlfriend went home to visit her family, and I was with a different woman every night she was gone. I took sleeping pills because I couldn’t sleep. When I couldn’t sleep, I walked around my house, throwing and breaking things. One night, I dreamed of Gary being tied to a stake and bayoneted repeatedly, while I stood on the other side of a fence, unable to reach him. In the morning, I heard of another, nearly fatal suicide attempt by Gary.

I desperately wanted to see him, to reach out to him at last, to achieve a reconciliation. I was not resigned to his execution.

Draper Prison is located in the Salt Lake Valley at a place known as the ‘Point of the Mountain’. The valley is heavily polluted, and one doesn’t become aware of the surroundings until the final, winding approach to the prison. Draper rests at the centre of a flat basin, surrounded by tall, sharply inclined snowy slopes. It offers the most beautiful vista in the entire valley.

My brother Frank and I were led into a triangular room in which no guards were present. Gary strolled in. He was dressed in prison whites and in red, white and blue sneakers. He twirled a comb and smiled broadly. I’d seen so many photos and film clips that showed him looking grim and cold that I’d forgotten how charming he could be. ‘You’re looking as fit as ever,’ he said to Frank. ‘And you’re just as damn skinny as ever,’ he said to me. He rearranged the benches in front of the guardroom window. ‘So those poor fools can keep an eye on me,’ he said.

For the first few minutes we exchanged small talk. Then I spoke of the prospect of intervention, but Gary cut me off. ‘Look, I don’t want anybody interfering, no outside causes, no lawyers like Amsterdam.’ He took hold of my chin. ‘He’s out of this, I hope.’ Before I had a chance to reply, the visitors’ door opened and Uncle Vernon and Aunt Ida entered. The visit became an ordeal. Gary and Vernon did most of the talking, discussing the people Gary wanted to leave money to and cracking macabre jokes. Vernon had brought along a bag of green T-shirts adorned with a computerized photo of Gary and the legend, ‘Gilmore – death wish’. Vernon and Gary discussed the possibility of Gary wearing one on the morning of the execution and Vernon auctioning it off to the highest bidder.

As we were leaving, Gary offered me a T-shirt. I didn’t accept it.

‘Well,’ he drawled, smiling, ‘it’s a little big for you, but I think you can grow into it.’ I took the shirt.

I visited Gary again. I forced myself to ask the question I’d been building up to: ‘What would you do if we were able to stop this?’

‘I don’t want you to do that,’ he said gravely.

‘That doesn’t answer my question.’

‘I’d kill myself. Look, I’m not watched closely in this place. I could’ve killed myself any time in the last two weeks. But I don’t want to. Besides, if a person’s dumb enough to murder and get caught, then he shouldn’t snivel about what he gets.’

Gary went on to talk about prison life, describing some of the brutality he had witnessed and some that he had fostered. He was terrified of a life in prison. ‘Maybe you could have my sentence commuted, but you wouldn’t have to live that sentence or be around when I killed myself.’ The fear in his eyes was most discernible when he spoke about prison, far more than when he spoke about his own impending death – maybe because one was an abstraction and the other an ever-present concrete reality. ‘I don’t think death will be anything new or frightening for me. I think I’ve been there before.’

We talked for hours, or rather Gary talked. This was the first real communication we had had in years; neither of us wanted to let go. I told Gary that I was supposed to leave that night, to go back home and spend the weekend with our mother. ‘Can’t you stay for one more day?’ he asked. I agreed to return the next day.

I reached our lawyer and told him that I had decided not to intervene to block the execution. Telling him was almost as hard as making the decision. I could have sought a stay, signed the necessary documents and gone away feeling that I had made the right decision, the moral choice. But I didn’t have to bear the weight of that decision; Gary did. If I could have chosen for Gary to live, I would have.

On Saturday 15 January, I saw Gary for the last time. Camera crews were camped in the town of Draper, preparing for the finale.

During our other meetings that week, Gary had opened with friendly remarks or a joke or even a handstand. This day, though, he was nervous and was eager to deny it. We were separated by a glass partition. ‘Naw, the noise in this place gets to me sometimes, but I’m as cool as a cucumber,’ he said, holding up a steady hand. The muscles in his wrists and arms were taut and thick as rope.

Gary showed me letters and pictures he’d received, mainly from children and teenage girls. He said he always tried to answer the ones from kids first, and he read one from an eight-year-old boy: ‘I hope they put you some place and make you live forever for what you did. You have no right to die. With all the malice in my heart. [name.]’

‘Man, that one shook me up for a long time,’ he said.

I asked him if he’d replied to it.

‘Yeah, I wrote, “You’re too young to have malice in your heart. I had it in mine at a young age and look what it did for me.”‘

Gary’s eyes nervously scanned some letters and pictures, finally falling on one that made him smile. He held it up. A picture of Nicole. ‘She’s pretty, isn’t she?’ I agreed. ‘I look at this picture every day. I took it myself; I made a drawing from it. Would you like to have it?’

I said I would. I asked him where he would have gone if he had made it to the airport the night of the second murder.

‘Portland.’

I asked him why.

Gary studied the shelf in front of him. ‘I don’t want to talk about that night any more,’ he said. ‘There’s no point in talking about it.’

‘Would you have come to see me?’

He nodded. For a moment his eyes flashed the old anger. ‘And what would you have done if I’d come to you?’ he asked. ‘If I had come and said I was in trouble and needed help, needed a place to stay? Would you have taken me in? Would you have hidden me?’

The question had been turned back on me. I couldn’t speak. Gary sat for a long moment, holding me with his eyes, then said steadily: ‘I think I was coming to kill you. I think that’s what would have happened; there may have been no choice for you, no choice for me.’ His eyes softened. ‘Do you understand why?’

I nodded. Of course I understood why: I had escaped the family – or at least thought I had. Gary had not.

I felt terror. Gary’s story could have been mine. Then terror became relief – Jensen and Bushnell’s deaths, and Gary’s own impending death, had meant my own safety. I finished the thought, and my relief was shot through with guilt and remorse. I felt closer to Gary than I’d ever felt before. I understood why he wanted to die.

The warden entered Gary’s room. They discussed whether Gary should wear a hood for the execution.

I rapped on the glass partition and asked the warden if he would allow us a final handshake. At first he refused but consented after Gary explained it was our final visit, on the condition that I agree to a skin search. After I had been searched by two guards, two other guards brought Gary around the partition. They said that I would have to roll up my sleeve past my elbow, and that we could not touch beyond a handshake. Gary grasped my hand, squeezed it tight and said, ‘Well, I guess this is it.’ He leaned over and kissed me on the cheek.

On Monday morning, 17 January, in a cannery warehouse out behind Utah State Prison, Gary met his firing squad. I was with my mother and brother and girlfriend when it happened. Just moments before, we had seen the morning newspaper with the headline execution stayed. We switched on the television for more news. We saw a press conference. Gary’s death was being announced.

There was no way to be prepared for that last see-saw of emotion. You force yourself to live through the hell of knowing that somebody you love is going to die in an expected way, at a specific time and place, and that there is nothing you can do to change that. For the rest of your life, you will have to move around in a world that wanted this death to happen. You will have to walk past people every day who were heartened by the killing of somebody in your family – somebody who you knew had long before been murdered emotionally.

You turn on the television, and the journalist tells you how the warden put a black hood over Gary’s head and pinned a small, circular cloth target above his chest, and how five men pumped a volley of bullets into him. He tells you how the blood flowed from Gary’s devastated heart and down his chest, down his legs, staining his white pants scarlet and dripping to the warehouse floor. He tells you how Gary’s arm rose slowly at the moment of the impact, how his fingers seemed to wave as his life left him.

Shortly after Gary’s execution, Rolling Stone offered me a job as an assistant editor at their Los Angeles bureau. It was a nice offer. It gave me the chance to get away from Portland and all the bad memories it represented.

I moved to Los Angeles in April 1977. It was not an easy life at first. I drank a pint of whisky every night, and I took Dalmane, a sleeping medication that interfered with my ability to dream – or at least made it hard to remember my dreams. There were other lapses: I was living with one woman and seeing a couple of others. For a season or two my writing went to hell. I didn’t know what to say or how to say it; I could no longer tell if I had anything worth writing about. I wasn’t sure how you made words add up. Instead of writing, I preferred reading. I favoured hard-boiled crime fiction – particularly the novels of Ross Macdonald – in which the author tried to solve murders by explicating labyrinthine family histories. I spent many nights listening to punk rock. I liked the music’s accommodation with a merciless world. One of the most famous punk songs of the period was by the Adverts. It was called ‘Gary Gilmore’s Eyes’. What would it be like, the song asked, to see the world through Gary Gilmore’s dead eyes? Would you see a world of murder?

All around me I had Gary’s notoriety to contend with. During my first few months in LA – and throughout the years that followed – most people asked me about my brother. They wanted to know what Gary was like. They admired his bravado, his hardness. I met a woman who wanted to sleep with me because I was his brother. I tried to avoid these people.

I also met women who, when they learned who my brother was, would not see me again, not take my calls again. I received letters from people who said I should not be allowed to write for a young audience. I received letters from people who thought I should have been shot alongside my brother.

There was never a time without a reminder of the past. In 1979, Norman Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song was published. At the time, I was living with a woman I loved very much. As she read the book, I could see her begin to wonder about who she was sleeping with, about what had come into her life. One night, a couple of months after the book had been published, we were watching Saturday Night Live. The guest host was doing a routine of impersonations. He tied a bandana around his eyes and gleefuly announced his next subject: ‘Gary Gilmore!’ My girlfriend got up from the sofa and moved into the bedroom, shutting the door. I poured a glass of whisky. She came out a few minutes later. ‘I’m sorry,’ she said, ‘I can’t live with you any more. I can’t stand being close to all this stuff.’ She was gone within a week.

I watched as a private and troubling event continued to be the subject of public sensation and media scrutiny; I watched my brother’s life – and in some way, my life – become too large to control. I tried not to surrender to my feelings because my feelings wouldn’t erase the pain or shame or bad memories or unresolved love and hate. I was waiting to be told what to feel.

Gary Gilmore arrives in court to hear the judge set the third date for his execution, 15 December 1975

I tried to leave the reality of my family behind me. I visited my mother in Oregon a couple of times a year, but the visits were always disturbing. She talked incessantly about the past – about her childhood in Utah, about Gary’s death, about the family curse – and her health was bad. After Gary’s death, she refused to leave her trailer, and my brother Frank and I could not convince her to see a doctor.

In the last few years of her life, my mother began to tell my brother Frank and me stories that were like confessions. She told us how she had hated her father: he had been a cruel and authoritarian Mormon patriarch; he had beaten his children with a whip; he had tormented and humiliated her brother George terribly. She never forgave him for dragging her to the hanging in the meadow. She had not, in fact, managed to keep her face buried in his side that morning. In the instant before the trapdoor was pulled, her father grabbed her by the hair and yanked hard, forcing her to watch the man as he dropped to death. On the ride back, she decided that she would never forgive her father, and that she would live a life to spite his hard virtue.

In June 1980, her stomach ruptured. She was sitting in the small front room of her trailer, talking to my brother about all the pain her father and her husband had left her with, and she started to lose blood. We brought her to the hospital. She fell into a coma, and a few days later she died.

I helped my brother bury her. Frank was forty years old, and he seemed lost without her.

The night of her funeral, Frank and I stayed at a friend’s house. I had to fly back to Los Angeles the next day. I told Frank to come to California and stay with me for a while. In the morning we said goodbye. I watched him turn and walk away. I wrote to him as soon as I got back to LA. Within a few days, the letter came back. It was marked: no longer at this address. no forwarding address. For a long time I tried to find him, but I never did. I have not seen him since that morning we said goodbye to each other on that haunted stretch of Oregon highway. He seemed to have walked into the void with all the other ghosts.

A few months after my mother’s death, I fell in love. Like me, she came from a family with a history of death and brutality. We believed we could help each other make up for our losses and in August 1982 we were married.

The marriage did not last – how could it? My wife and I brought along too many family demons for one house. I hadn’t so much loved her as tried to save her, in order to atone for my failure to save my brother. I went on to pursue one vain relationship after another, in a desperate attempt to discover or build the sort of family that had not been present in my childhood. I sometimes sabotaged these relationships, as a way of never having the family life I claimed I wanted so much – of not passing to my children the inheritance of violence and ruin that I feared might be genetic. For far too long, I stopped wanting any home or family, because it hurt too much, felt too much like irredeemable failure, to want those things and yet feel I would never have them, or might damage them once I did have them.

And then, a few years ago, I decided I was ready to move back home. I believed I could live again in the place where so much ruin had occurred and simply ignore all that ruin; I thought I might seize those dreams I had wanted for so long. But I came face-to-face with that damn family spectre, and it devastated my life and also my hope, and I returned to my friends and life in Los Angeles.

Can murder’s momentum end? It has been fifty years since Gary was born. It has been over fourteen years since he committed his murders and died for them. You would think that would be enough time to forget, to redeem. But the past never stops.

Early one evening a few months ago a friend called to tell me that A Current Affair – a nationally syndicated programme that takes real-life scandal and repackages it into a news-entertainment format – would be running a segment that night on my brother. The show’s producers had tracked down Nicole and persuaded her to grant an interview about Gary and his murders and execution – the first lengthy television interview she had ever agreed to do.

It came as a bit of a surprise to me that, after well over a decade, Gary’s relationship with Nicole and his death would still be hot news. Maybe it was a slow day for scandalmongering. I tuned in the programme, expecting something tasteless, and what I saw was certainly that. But it was also strangely affecting in ways I had not expected: there was news footage of Gary being led to and from court during the many hearings of those last few months, handcuffed and dressed in prison whites, his wary, appraising eyes scanning the cameras that surrounded and documented him. I remembered watching this footage back in the daze and fury of 1976. Fourteen years later he looked cold-blooded, arrogant, deadly. He also looked plain scared, and he looked like my brother. That is, like somebody I both loved and hated; somebody who had transformed my life in ways that could never be repaired; somebody I had missed very much in the years since his death and I wished I could talk with, no matter how painful the talking might be.

The programme’s message was sordid and mean-spirited. The point, it seemed, was to try to hang much of the blame for Gary’s murders on Nicole. Nicole described the last time Gary had hit her. ‘I had been hit before by men,’ she said, ‘and I told myself, “I’m leaving.” No matter what I did, I did not deserve that. He knew that was how I felt. And when I looked at him, I knew that when I went, he would kill someone. I knew that if I left him, somebody would die for it.’

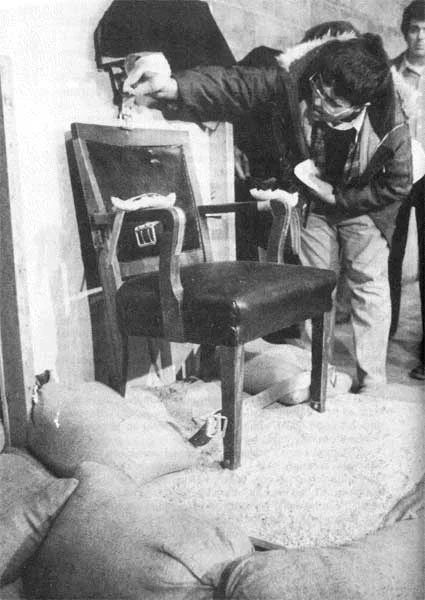

Journalists examine the chair to which Gary Gilmore was strapped for execution.

‘And yet you left anyway?’ the interviewer asked.

Nicole looked off camera for a moment. ‘One of the greater regrets of my life,’ she said.

The interviewer’s implication couldn’t have been plainer: Nicole shared in the blame. ‘How could you say you loved somebody so cold-blooded?’ he asked at the end.

‘There isn’t a day goes by,’ said Nicole, ‘his name doesn’t go through my head. He came into my life, he loved me, and he destroyed all the good that was there.’

‘If you could erase Gary Gilmore from your life, would you?’

Again, another glance away, and she shook her head.

‘And you say that,’ the interviewer asked, ‘knowing that if you erased Gary those two men would still be alive, those men’s children would still have their fathers… ‘

Finally, Nicole closed off the question. ‘Yeah,’ she said, nodding. ‘Yeah, then I would.’

The camera cut to the programme’s host, who had an expression of smug disgust. ‘Tough to shed a tear for her,’ he said.

I turned off the television and the lights in my front room, and I sat in the dark for hours.

Only a few months before, I had gone through one of the worst times of my life – my brief move to Portland and back. What had gone wrong, I realized, was because of my past, something that had been set in motion long before I was born. It was what Gary and I shared, more than any blood tie: we were both heirs to a legacy of negation that was beyond our control or our understanding. Gary had ended up turning the nullification outward – on innocents, on Nicole, on his family, on the world and its ideas of justice, finally on himself. I had turned the ruin inward. Outward or inward – either way, it was a powerfully destructive legacy, and for the first time in my life, I came to see that it had not really finished its enactment. To believe that Gary had absorbed all the family’s dissolution, or that the worst of that rot had died with him that morning in Draper, Utah, was to miss the real nature of the legacy that had placed him before those rifles: what that heritage or patrimony was about, and where it had come from.

We tend to view murders as solitary ruptures in the world around us, outrages that need to be attributed and then punished. There is a motivation, a crime, an arrest, a trial, a verdict and a punishment. Sometimes – though rarely – that punishment is death. The next day, there is another murder. The next day, there is another. There has been no punishment that breaks the pattern, that stops this custom of one murder following another.

Murder has worked its way into our consciousness and our culture in the same way that murder exists in our literature and film: we consume each killing until there is another, more immediate or gripping one to take its place. When this murder story is finished, there will be another to intrigue and terrify that part of the world that has survived it. And then there will be another. Each will be a story; each will be treated and reported and remembered as a unique incident. Each murder will be solved, but murder itself will never be solved. You cannot solve murder without solving the human heart or the history that has rendered that heart so dark and desolate.

This murder story is told from inside the house where murder was born. It is the house where I grew up, and it is a house that I have never been able to leave.

As the night passed, I formed an understanding of what I needed to do. I would go back into my family – into its stories, its myths, its memories, its inheritance – and find the real story and hidden propellants behind it. I wanted to climb into the family story in the same way I’ve always wanted to climb into a dream about the house where we all grew up.

In the dream, it is always night. We are in my father’s house – a charred-brown, 1950s-era home. Shingled, two storey and weather worn, it is located on the far outskirts of a dead-end American town, pinioned between the night lights and smoking chimneys of towering industrial factories. A moonlit stretch of railroad track forms the border to a forest I am forbidden to trespass. A train whistle howls in the distance. No train ever comes.

People move from the darkness outside the house to the darkness inside. They are my family. They are all back from the dead. There is my mother, Bessie Gilmore, who, after a life of bitter losses, died spitting blood, calling the names of her father and her husband – men who had long before brutalized her hopes and her love – crying to them for mercy, for a passage into the darkness that she had so long feared. There is my brother Gaylen, who died young of knife wounds, as his new bride sat holding his hand, watching the life pass from his sunken face. There is my brother Gary, who murdered innocent men in rage against the way life had robbed him of time and love, and who died when a volley of bullets tore his heart from his chest. There is my brother Frank, who became quieter and more distant with each new death, and who was last seen in the dream walking down a road, his hands rammed deep into his pockets, a look of uncomprehending pain on his face. There is my father, Frank Sr, dead of the ravages of lung cancer. He is in the dream less often than the other family members, and I am the only one happy to see him.

One night, years into the same dream, Gary tells me why I can never join my family in its comings and goings, why I am left alone sitting in the living room as they leave: it is because I have not yet entered death. I cannot follow them across the tracks, into the forest where their real lives take place, until I die. He pulls a gun from his coat pocket. He lays it on my lap. There is a door across the room, and he moves towards it. Through the door is the night. I see the glimmer of the train tracks. Beyond them, my family.

I do not hesitate. I pick the pistol up. I put its barrel in my mouth. I pull the trigger. I feel the back of my head erupt. It is a softer feeling than I expected. I feel my teeth fracture, disintegrate and pass in a gush of blood out of my mouth. I feel my life pass out of my mouth, and in that instant, I collapse into nothingness. There is darkness, but there is no beyond. There is never any beyond, only the sudden, certain rush of extinction. I know that it is death I am feeling – that is, I know this is how death must truly feel and I know that this is where beyond ceases to be a possibility.

I have had the dream more than once, in various forms. I always wake up with my heart hammering hard, hurting after being torn from the void that I know is the gateway to the refuge of my ruined family. Or is it the gateway to hell? Either way, I want to return to the dream, but in the haunted hours of the night there is no way back.