In this village

In this village unsold horses stand by the dozens in dark, small rooms. The hand that sometimes dusts them and lets in the light also lets the dust fall on the ground. What is swept off the horses falls below and grows in thickness, piles up over months and years, till the horses stand up to their chests in a forest of dust. It would be too much work to remove all the horses and sweep the floor and put them back again.

Above the closed rooms, the International Space Station moves swiftly across the dark night sky, the brightest and swiftest object in the darkness after the moon. It appears 10 degrees above north-north-west and disappears 10 degrees above south-east.

On the red soil plains of Bankura centuries ago, no one knows quite how, the fired clay horse became an offering to the gods. It was offered so a wish could be fulfilled, given in gratitude when a child began to crawl. It was found on the tombs of saints. The cow and the bull lived beside all that was everyday. The horse was never everyday, never a fact, and the maker of the fired clay horse may never have seen one with his own eyes.

The horse is not native to these plains, or even to the subcontinent. It came from somewhere that is too far to walk to, from as far away as the most unreasonable desire, the most devastating hope.

The horse came from Central Asia, very likely before the Aryans, but certainly with them over the mountains, as they moved into the subcontinent. Then epochs later again with the Mughals, and once more with the British, this time in ships over the sea. Many died from seasickness.

Thirty one fired clay horses, almost three-feet high, stand at the bottom of a banyan tree, an offering to the gods. They have wide jaws, long necks, stout legs, a saddle carved with flowers and leaves, and a small tail.

Leaving behind the red soil of Bankura, the horse enters living rooms, with its solemn, vigilant face, an object separated from its use, matter lasting so much longer than human gesture.

On the International Space Station an orange zinnia flower blooms.

In the fierce heat of May once, on this red soil parched with thirst, we looked deep into a well, into dark water which healed our scorched eyes, we saw ourselves reflected among yellow and brown fungus floating on the surface. Someone lowered a tin mug into it and scooped up the water, and we drank and drank, we quenched our thirst, and instead of being ill from the fungus and molds we were well as never before, and when night came, we could see again, so we lay down on the red earth and looked up at a new sky of stars.

The horse was a wish for the power of the conquerors, who always came on horseback, even more it was a wish for boundless spaces, a wish for the inexpressibly wide and broad, for the unharnessing of human life.

Every twenty four hours, as it circles the earth, the international space station sees thirty two nights and dawns.

Every day

Every day something else sets over the subcontinent along with the sun. Today it is the crouched man, sullen and taciturn. Hundreds of horses have sprung from his hands. There is mud on his feet, mud on his fingers, his skin is withered from working with water and earth. Crouched, he travels towards his own extinction. He wants to whip the future which is always somewhere else, wants to watch it whimper in terror, wants to shatter its complacent stride forever. Only the trees and rivers have a future that stays with them, wherever they are. He is jealous of the sun which will rise again. He crouches and turns his face away from the light, turning and turning away till his neck can swivel no further. His sons do not crouch near the potter’s wheel, with erect spines they leave to work as sweepers in humid, dilapidated, malarial government offices. The horses he made never looked him in the eye. Their gaze was always turned towards infinity. That same infinity that cares nothing for the movement of time, does not acknowledge the future, that crucible of fate. That same infinity that spills endlessly from the eyes of god. No moon and stars follow in the darkness that comes after the crouching man sets. Like other things become extinct, he rotates on his own axis. If he looked up he would see palm leaf fans revolve, and scalloped bell metal bowls, and clay pitchers, each thing made by the hand, related like planets.

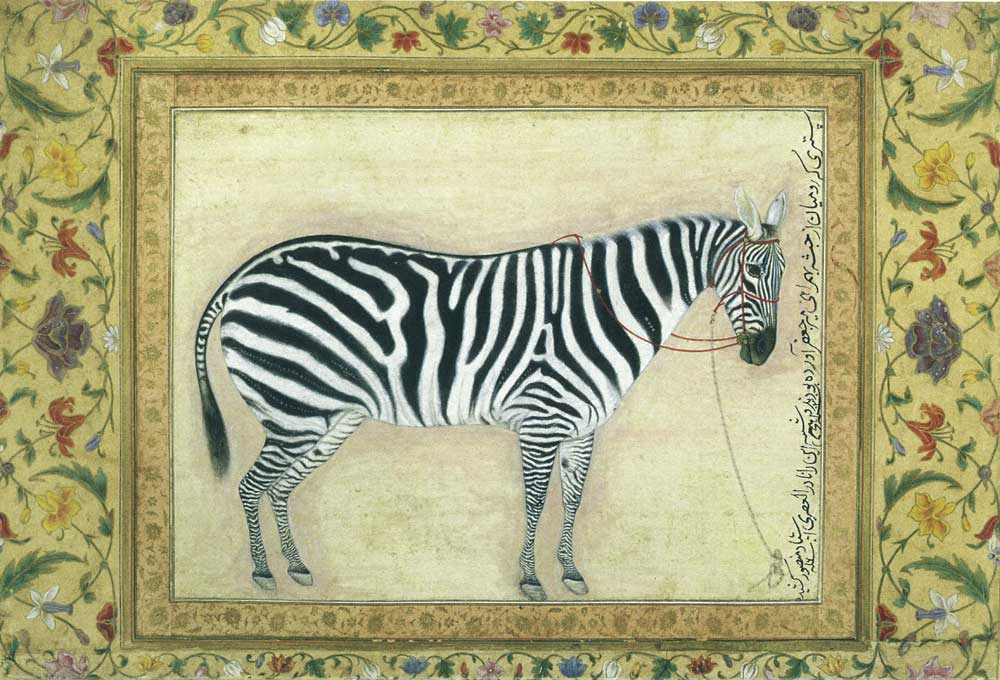

The Emperor Jehangir, with his hand on the flank of an Abyssinian zebra, revolves in that same darkness. The zebra was given to him as a gift in his sixteenth regnal year, 1621. Jehangir repeatedly touched the animal to see whether the stripes on it were painted. He had never ever seen anything like it before. ‘One might say that the painter of fate, with a strange brush, had left it on the page of the world,’ he wrote. Zebras are alive in the plains and grasslands of Africa, Jehangir is alive in his portraits and monuments, it is the awe that is extinct, part of a species of emotions in which the centre is outside the self.

Ustad Mansur, master painter at the Emperor’s court, painted the zebra at the Emperor’s orders.

We are

We are the slow churning of cement mixers, the leaden mass of concrete, we are the pools of fresh water at construction sites from where the Aedes mosquitoes rise with the sun, we are the debris of old mansions grown useless, the grey air filled with abrasive particles hanging low in the early morning light, we are the strained breath and the respiratory infection, the pneumatic drill that bores through the universe, we are our deflated pasts no matter where they were, inflated futures always in the future, the fevered, dengue ridden present, the stench of urine from roadsides and bushes and vacant plots making a useless ornament out of sudden flowers, we are the flared temper which lights our way, the leper begging with his stumps since the hands that move and create life are long gone, we are the holes in the road through which we fall but never far enough, we are the rising prices and the broken buyers both, the lit candles, the flowers offered, the bruised knees and hands of prayer, the din of rituals, the used up rag of belief, we are the women in crowded banks that lock in the smell of sweat, planning their savings so they can leave—for New Zealand, Australia, Canada, America, Dubai, Hong Kong, Singapore, we are the streetlights dimmed by the hazy night, and all that cannot be tamed is far away, a lake by a hill, a river’s looping course, we are the lonely skywalks at night where idle men wait to attack exhausted women going home, we are falling debris, dust and mud, we are rising steel and iron and glass, an Alpha city like Milan, Madrid and Moscow, impacting the whole world, falling against it, pushing it on its axis, we are the man slamming a woman’s head against the windshield of a sedan as he drives, we are the man who is passing by that calls the police, we are the police who ask him to call a different police station, under a sullen sky the irascible wind blows, we are the roads whose innards are dug up and heaped on either side, we are the stumps of trees chopped down to make room for these roads, trees that have been hacked by ebony coloured men as if they were hacking at the body of god, the same men whose ancestors would have broken stone to build god’s body and his home, we are the traffic permanently stalled where patience and impatience must alternate like inspiration and expiration and the ambulance that has right of way is deeply resented, we are the young men who break the nose of someone who tells us not to litter as the sun sets over the sea before us, we are the miniscule artificial gardens where only the very old hobble forward, the cratered pavement with a jutting brick or an iron rod sprouting forth that will trip us up, we carry the heat on our backs like a sack of stones, only one day in winter is there a benevolent light blue sky, and sleep when it comes is held at bay by regrets that rise like reflux in the throat, or shredded by packs of stray dogs that bite the darkness, we are the Arabian Sea wrecked by the refuse in our gut, moving slowly with a long way to go, because only very far away, somewhere, thousands of miles from here, will we become pure, with only salt and fish that live and weeds and the wind.

Image: Burchell’s Zebra, inscribed by Emperor Jehangir, as painted by Nadir ul-Asri Ustad Mansur, 1621. Folio, Minto Album, Victoria & Albert Museum