In the mid-1980s a bunch of us who were living on the dole in south London got work with a market research company specializing in train travel. Half the time we were at the offices in Richmond, collating data in what was basically a very large cupboard that smelled of the fried egg sandwiches we ate for breakfast. The rest of the time was spent on trains collecting that data: conducting interviews, handing out questionnaires or using little clickers to count the numbers of passengers who got on and off at a given station. We went all over the country, travelling first class with all-station passes. Because the working day often began in places far from London we had to stay in hotels. If we had to work in Scotland the company reduced costs by booking compartments on the sleeper train. They also saved money by booking two people to a room so if you were part of a couple, as I was, this meant we could have hotel and sleeper sex: a lifestyle beyond our financial dreams at that point.

The pass was strictly to be used for work purposes only but we used it to travel for free, to go wherever we wanted. That was great, though it was a bit like the later benefit of free flights from air miles: after spending a week on trains the last thing you wanted was to travel by train at the weekend. But we did, to all sorts of places, because we knew that the opportunity might not come again. We’d meet up in some spot we’d heard of, that someone said would be fun, to drink beer on a beach or get stoned in the ruins of an abbey. An interesting cathedral was incentive enough to travel hundreds of miles. The only weird thing about these gatherings is that we’d all be dressed smartly to avoid detection on the trains. To passersby we must have looked like a sect of Christians or Jehovah’s Witnesses that had become sloppy and raucous under the influence of drink and drugs. The other cool thing was that we invoiced the firm under false names, cashing our cheques at the local branch of Lloyds while continuing to claim our dole money. We were like Cordelia: most rich being poor.

On the trains, on working days, I was highly motivated. My goal was to get all the forms filled out as quickly as possible. One survey involved finding out more about the use of Parkway stations – stations that people drove to and parked at before taking the train. I was in such a hurry to give out forms that I didn’t pay any attention to whom I was speaking.

‘Did you drive to the station today?’ I said automatically, unthinkingly, to a man in an aisle seat who had just got on at Bristol Parkway.

‘I’m blind,’ he said stiffly. I looked at him for the first time: grey hair, smart jacket, white cane, dark glasses, book of braille on the table in front of him . . . Yep, he was so thoroughly decked out in all the signifiers of blindness he could have been an actor playing the role of a blind person.

‘I understand. But did you drive to the station?’ I said, struggling to keep a straight face as I tried to salvage the situation by asking again the question I was paid to ask.

‘No I did not,’ he said, sounding understandably shirty this time. ‘Because I am blind. As I have said.’

‘OK, thank you. Not to worry,’ I said, wobbling on down the carriage. Conscious that they were employing a bunch of graduate dossers the company had been at pains to improve their image and raise standards of conduct so I was worried that this insensitivity on my part – cross-examining the blind guy like a heartless barrister – might cause problems down the line. I was wearing a lapel badge with both the company’s and my (real) name printed clearly but he could not have seen that of course. Still, the people crowded in the three seats around him – none of whom, it turned out, had driven to the station – could easily have ratted me out. I hurried back to the first-class carriage where my friends were busy filling out forms. That was the other way to speed things up: to fill out the forms ourselves and not bother with the time-wasting inconvenience of consulting actual passengers.

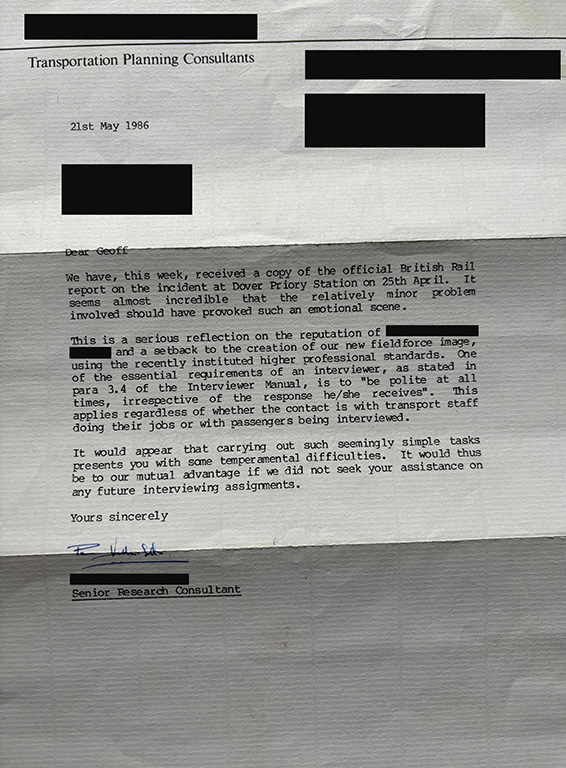

It was a great gig while it lasted but in my case it didn’t last long after that regrettable incident. On another trip I forgot some part of the various bits of ID we were obliged to carry at all times and got into a fracas with the staff at Dover Priory station and I was lucky to avoid getting into serious trouble. Well, not that lucky. A few weeks later I received a letter which I’ve just found, dated 21 May 1986:

Various other friends fell victim to this purging in the name of professionalism but I was the first to go, the trail-blazer and pioneer. I’d been sacked from another job several years earlier – my first proper salaried job after leaving Oxford. As was the case with that dismissal this one was entirely justified but I still felt hard done by, wronged, persecuted. I was a few weeks short of my twenty-eighth birthday. Later that year I would publish my first book, but in many ways I was still living like a student, a drop-out, a teenager.

Thirty years later, I reviewed an amazing book of photographs by Mike Brodie documenting the lives of his friends, young American kids living like hobos, hopping freights across the USA. It was called A Period of Juvenile Prosperity and I’m looking at it now. My life is full of regrets – I sometimes think I regret everything about my life – but I’ve never regretted the time spent riding the rails of Thatcher’s Britain, claiming benefits and being paid to do market research, and I don’t regret getting thrown under the bus either, if one can call a train a bus. The reason I always tried to get the forms filled out as quickly as possible was so that I could spend the rest of the journey reading in my first-class seat: a worthy and laudable ambition. That was always the gauge of any employment back then: how much time it afforded you to not do the work, to get paid to read instead. Beckoning just out of sight, beyond the next station on the map, as it were, was the job – the life – that involved nothing but reading: that’s where I wanted to go, what I was training for.

Image © Europeana