How do you persuade a thousand dogs to walk into a fire? How do you persuade them, as it were, to commit suttee? A thousand stray and rather wild dogs at that, all of whom need to be killed for urgent geopolitical reasons, to keep London and Washington happy. On the island of Diego Garcia, on an afternoon of fierce heat in spring 1971, this was the problem facing Sir Bruce Greatbatch, KCVO, CMG, MBE, who was then acting in his capacity as Governor of the Colony of the Seychelles and Commissioner of a newly established and then little-known imperial entity called the British Indian Ocean Territories.

It was hardly the crowning moment of Sir Bruce’s long colonial career, which had unrolled its stately way over four decades of administering the subject peoples of King George VI and then his daughter, Queen Elizabeth II, in parts of their empire ranging from northern Nigeria to Barbados. Here, on a tiny and hitherto insignificant speck of coral limestone at a point in the Indian ocean equidistant from Sri Lanka, Mombasa and the Arabian peninsula, Sir Bruce was compelled to supervise, not a Queen’s Birthday Party or the opening of a Dominion parliament, but the slaughter of a thousand mongrels.

Sir Bruce had the means at his disposal. On an island which had once harvested its coconut crop to produce coconut oil, there was a long, low brick-built shed known as the coconut calorifier. The shed had two shelves ranged one above the other, the upper to hold the flesh of hundreds of coconuts, the lower to hold the coconuts’ husks. By setting the husks on fire, the flesh above would be cooked and its water content (fifty per cent) evaporated until it became copra, an edible fat from which oil can be crushed. An economical system on Diego Garcia – all parts of the nut were used, no extra cost of imported fuel – but one designed for the inanimate. Still, this was to be the pyre. A ton or so of husks were heaped inside and set alight that day, sending up flames and billows of black smoke. Of course, the dogs were recalcitrant: they kept escaping to the beach and turning viciously on their whippers-in.

It took several hours, this great imperial dog-durbar, and must have tested Sir Bruce to the limits of his ingenuity. But eventually, with the aid of rifles, strips of strychnine-laced beef and whips made from palm fronds, the dogs were all herded or dumped dead inside the shed. Whereupon, acting on a plan drawn up as part of the retreat from this particular corner of the British Empire, Sir Bruce had the fires restoked and the calorifier sealed with closely fitting steel plates, and the dogs were promptly – or, according to contemporary reports, really rather slowly – burned or suffocated. An hour or so later, as the sun was going down, their remains were inspected and Sir Bruce was able to declare the Crown Colony of the British Indian Ocean Territories to be utterly empty of all creatures large enough to be a nuisance.

The government of the United States was informed of the fact by diplomatic telegram. Some years before, American generals and admirals had insisted on this emptiness before they would consider building what they then found it convenient to call ‘a small communications facility’ on the territory’s islands. Now a treaty signed between Britain and America in 1966 could be put into effect.

Before the day was out a detachment of Seabees, which had been bobbing about offshore waiting for orders, landed with a dozen mighty earth-moving trucks, their tyres three times as tall as a man. Soon they were churning up the soft pink sand and laying the foundations of what was to become one of the largest and most important foreign military bases America has ever constructed in peacetime. ‘Under no circumstances refer to what is being built as a “base”,’ wrote a nervous official in the British Foreign Office to his ambassadors in Washington and at the United Nations, around the time when the Seabees first ground their way onshore. But a base is very much what was built.

Thirty years later, nearly 4,000 American sailors and contractors live on Diego Garcia. There are two bomber-capable runways, each two and a half miles long; two ‘nuclear-cleared berths’, and a network of jetties and piers. The lagoon now has deep-water anchorages for thirty ships. The skyline of the island has been speared by arrays of towers, space-tracking domes, oil, petrol and aviation fuel dumps, barracks, weapons ranges, and training areas. By the summer of last year the US government was calling Diego Garcia an ‘all but indispensable platform’, absolutely central to American strategy for policing a large part of the world and in particular the Middle East.

Diego Garcia got its name from a Portugese navigator in the sixteenth century. On a map it looks like a child’s foot – the shapely little heel to the south, the lagoon entrance (which is now one of the world’s busiest military seaways) snaking between the big and the first toes. On the water tower by this entrance are painted the words: diego garcia: the footprint of freedom. And yet, despite its appearance as a tropical extension of maritime New Jersey, the island is still most decidedly not American.

It is British, a Crown Colony established in 1965 (and therefore Britain’s newest), little different in administrative status from the Falkland Islands, Bermuda, the Caymans or the dozen other relics of empire still ruled from London. Many Stars and Stripes flutter on Diego Garcia, but the flag that flies from the tallest of the island flagstaffs is the Union Jack. The most senior inhabitant of the island is not the resident American Vice-Admiral, but the British officer (normally a naval commander, two ranks below his counterpart) who heads what is known as Royal Naval Party 2002. Or rather, it is either him or, when she visits from London, Margaret Savill, a career diplomat and current BIOT Administrator.

The 4,000 American servicemen who are currently based there are supposed to obey laws (particularly the narcotics ordinances, which are the laws they most frequently break) that are administered on Her Majesty’s behalf either by Mr John White, the island Commissioner (who rarely visits, having more onerous tasks relating to the running of British diplomacy in East Africa which he handles from his desk in London); or by Miss Savill (who does go from time to time, taking the regular US Air Force’s six-hour C-130 flight from Singapore); or, empowered by ordinance to act for her, by twenty resident Royal Marines, six Scotland Yard policemen and a pair of often bewildered British customs officers who have been flown there on temporary secondment.

How and why did this curiosity come about? Thanks to a legal case, which last year resulted in one of the most damning verdicts on government behaviour ever to be reached by a British court, we now have the full, ignoble story. Six thick volumes of paper, most of them secret government documents, were produced in court. The details disclosed by them show Sir Bruce Greatbatch’s behaviour to be relatively benign. Comparing his small dog-holocaust to the other actions by his colonial colleagues, one thing seems clear: getting rid of Diego Garcia’s dogs had been perhaps the most difficult practical part of the operation. Getting rid of the human beings, some of whom had owned the dogs, had by contrast been a snap.

Someone should have smelled a rat when the British government took the unusual step of creating the new colony in the first place. It happened in the mid 1960s, when London was considering granting independence to its two major island possessions in the western Indian Ocean, the colonies of Mauritius and the Seychelles. The age of Empire was now coming to an end and with it Britain’s military bases in the East: bases in Hong Kong, Singapore, on the island of Gan in the Maldives and at Aden on the southern tip of the Arabian peninsula – all of them, sooner or later, were going to have to be abandoned.

Mao’s China was then a preoccupation among the West’s military strategists; it had recently invaded India and defeated the Indian army in a conflict over national frontiers in the Himalayas. To counter what was perceived as the Chinese threat (and Soviet influence in the Middle East, Africa and India), the USA needed a secure base in the Indian Ocean to replace the British bases; one free of local populations and the unpredictable behaviour of new and possibly unreliable nation states. A secret Anglo-American conference was held in London in February 1964 to discuss these matters. At this conference, officials happily discovered that there was one obscure archipelago in the very middle of the Indian ocean on which the RAF had long ago built a still usable emergency wartime airstrip.

A survey team was promptly dispatched and reported back that the strip, and the island on which it was located, could be turned into an ideal mid-ocean base with the expenditure of a few million pounds. There was plenty of room for a new airfield, there were ample protected waters for anchoring warships, there would be space enough to put barrack-fulls of soldiers and sailors. Moreover, at the time of the conference, the island was still a British colony. Not only that: with the help of some adroit diplomatic footwork, it might still be possible – if everything was kept quiet – to keep it British.

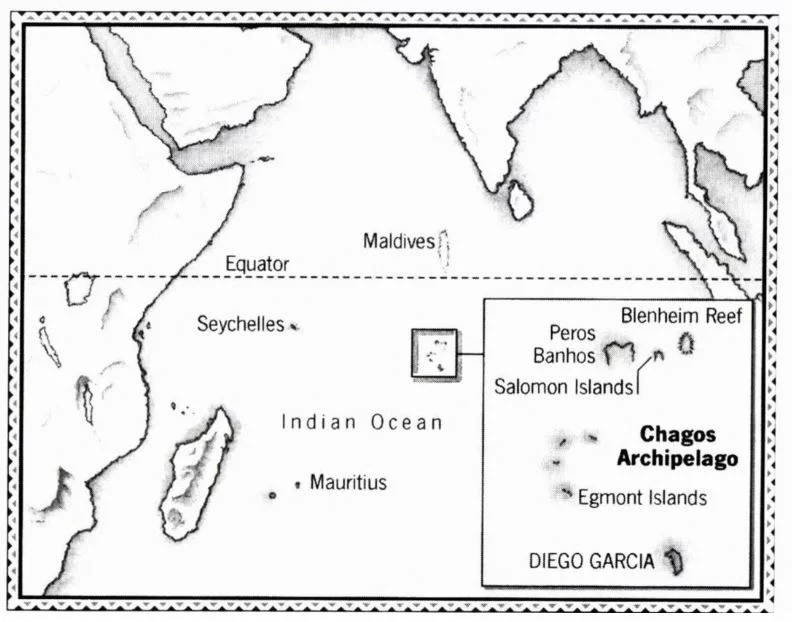

The islands of the archipelago, formally known as the Chagos Islands, were locally known as the Oil Islands – their coconut oil lit the few street lamps of Mauritius and the Seychelles. As a territory it was immense – 21,000 square miles of ocean covering the peaks and troughs of an ancient Gondwanaland mountain chain known as Limuria.

Only in eight places had the mountain tops reached close enough to the surface to allow corals to grow and break free of the water. Four of the resulting projections were merely reefs, strewn with the carcasses of wrecked ships and boiling with ragged white lines of surf. The other four were atolls proper, comprising a total of sixty-five individual coral islands arranged in groups: the Salomon Islands and the Peros Banhos atoll to the north, the Egmont Islands at the western edge and, down at the very southern tip of the territory, the curiously foot-shaped atoll, six miles wide and thirteen from heel to toe, of Diego Garcia. It was on this island – where there had once been a coaling station for Australia-bound steamships, and where the transoceanic telephone cable had a repeater station – that the RAF had built its strip.

The Oil Islands had been a minor administrative dependency of Mauritius ever since Britain had taken Mauritius from France as a colony under the First Treaty of Paris in 1814. An independent Mauritius would take the islands as part of its territory. But could an independent Mauritius be trusted to be an ally of the West? There was no certainty of that in 1964. ‘It would be unacceptable to both the British and the American defence authorities,’ wrote a Colonial Office minister on October 20 of that year, ‘if facilities of the kind proposed were in any way to be subject to the political control of ministers of a newly emergent independent state.’

And so a complicated deal was constructed. It was agreed that Mauritius could have all the independence it wanted, and promptly, if, in exchange for a cash payment of £3 million and an informal assurance that the US would look kindly on allowing Mauritian sugar imports, the Oil Islands were excluded – ‘excised’ was the word used – and retained by the British for as long as the British wanted to keep them.

The complexity of the deal that led to the establishment of what were to be called the British Indian Ocean Territories is perhaps understandable; what has only lately come to light is the deviousness – a degree of duplicity that became necessary because of one inconvenient discovery. The Oil Islands, obscure and unknown and forgotten though they might have been, also happened to be populated. People lived there, and had done for generations. That fact brought in its train a whole series of problems.

For a start, the Americans had long insisted that for security reasons there should be no people – either on Diego Garcia itself, or on any other of the outer atolls. The islands should be handed over, ‘fully sanitized’ and ‘swept’ (to use the words found in American papers of the time) and ready for the troops and nuclear submarines and bombers that were going to make the colony their home. ‘The primary objective in acquiring these islands,’ wrote an unnamed British official in an undated memorandum headed ‘Objectives’, ‘is to ensure that Britain has full title to and control over these islands…so that Britain and the United States should be able to clear the Territory of its current population.’ The Americans attached great importance to this freedom of manoeuvre and the British authorities went along with this demand. They assured the Americans that people on the atolls were no more than ‘rotating contract personnel’ – and just to make sure, in November 1965 and then again six years later, it was arranged for laws to be passed (actually, this being a colony, ordinances were written, without the requirement for any parliamentary consultation) which made it illegal for anyone to come to the islands ever again – or, indeed, to be there in the first place – without a permit. Anyone who was there could be deported, and put in prison while awaiting deportation – or, in the magisterial tones of the Order, ‘while awaiting removal…be kept in custody, and while so kept shall be deemed to be in lawful custody’.

The American requirement was one thing. The United Nations was quite another. Then as now the UN took a severe view of the sovereignty of any populated part of the world being arbitrarily changed without the inhabitants being consulted. The establishment of a new colony, with a brand new colonial citizenry, would need to have the status of its people (whether they were agitating for self-government, for example) regularly reported to a UN committee – a requirement agreed to by most of the world since the great decolonizations of the 1950s and 60s.

As early as May 1964 the British were aware of how anti-imperialist forces could seize and spread the news of a new colony. ‘Our partition of colonial territories against the will of the populace for UK-US strategic purposes would give the Soviet bloc a golden opportunity to attack us with Afro-Asian support,’ wrote an official in the Foreign Office Permanent Under-Secretary’s department to his British opposite number at the UN in New York. ‘Major damage would also be done to our general reputation vis-à-vis the Afro-Asian world; and we should have given the Communists an opportunity to damage our reputation very seriously indeed.’

But none of these problems would have unduly vexed the British if the islands had indeed been peopled only by rotating contract workers. If that had been the case, then so far as the Americans were concerned, the workers could have been told that their contracts were up, asked to leave, and their return for further work prohibited – brutish behaviour perhaps, but not illegal. And if the inhabitants had been merely passing through – if they had been Mauritians and Seychellois sent over by the company that worked the islands, the Chagos Agalega Oil Company, to work in the company copra mills and on the calorifiers and on pressing the oil – then the UN could either have been told of this fact in a perfunctory way, or not have been told at all. If the islanders had been transients, the UN’s requirements regarding transfer of sovereignty and regular reporting would not have applied.

Were they in fact transients? A Colonial Office official reported in 1964 that a ‘small number of people were born there and, in some cases, their parents were born there too’. This set off a flurry of alarm. More research was carried out – and the further discovery was made that the people who lived on the Chagos Islands were not in the main Mauritian and Seychellois but of East African origin, descendants of slaves who had been brought over in the early nineteenth century from Madagascar, Somalia and Mozambique.

There were more than 1,500 of these Chagos islanders. They spoke Creole. They were physically small and wiry. Most disturbing to the officials was the realization that a very large number of them were technically British subjects. Any who had been born on the islands and whose parents had been born there too were indisputably subjects of the Crown. What was more, many of them apparently knew of their status – a visitor in 1955 noted that the islanders were ‘lavish with their Union Jacks’ and they had serenaded him with a ragged version of the British national anthem, sung in English ‘with a heavy French accent’.

The discovery of the presence of 1,000 or more black, wiry, Creole-speaking Britons on islands that the British Government had promised to deliver to the Americans ‘swept clean’ startled the officials in London. There was panic and – from the very beginning – there was intentional duplicity.

‘The intention is that none of them should be regarded as being permanent inhabitants,’ was one of the earliest policy suggestions, written within days of the discovery in November 1965 by a member of the Colonial Office (which was merged with the Foreign Office in 1968). So far as the UN was concerned, another Colonial Office official wrote, ‘I would advise a policy of “quiet disregard” – in other words, let’s forget about this one until the United Nations challenge us on it.’

Diplomats suggested that the islanders be issued with documents showing their status as belonging to Mauritius or the Seychelles – even though they didn’t – in the hope of convincing both the UN and the islanders that the British had no need to ‘safeguard their democratic rights’. This might, the diplomat conceded, ‘be rather transparent’. Another colleague concurred, though he noted that there was in the Colonial Office ‘a certain old-fashioned reluctance to tell a whopping fib, or even a little fib, depending on the number of permanent inhabitants’.

Nonetheless, a fibbing policy began to take shape. London’s senior civil servants grew more candid. The Permanent Under-Secretary at the Colonial Office was Denis Greenhill – later elevated to the House of Lords as Baron Greenhill of Harrow. In August 1966 he had his secretary, Patrick Wright – later Sir Patrick – send to the British Mission at the UN a note from the Colonial Office which incorporated a gentlemen’s club kind of joke.

We must surely be very tough about this. The object of the exercise was to get some rocks which will remain ours; there will be no indigenous population except seagulls, who have not yet got a Committee (the Status of Women Committee does not cover the rights of Birds).

Having presumably chuckled at this little moment of drollery, Greenhill then added, in his own hand, this remark:

Unfortunately, along with the Birds go some few Tarzans and Men Fridays, whose origins are obscure, and who are being hopefully wished on to Mauritius etc. When this has been done I agree we must be very tough…

The policy towards BIOT’s population from now on would be that implied by the two strands of thinking in these private documents. There would be no indigenous population; the existing population would be ‘wished’ on to Mauritius.

Five years later, that is exactly what happened. Over a period of eighteen months beginning in 1971, a flotilla of boats entered the various harbours of the scattered atolls of the Chagos Islands and evacuated the islanders. Diego Garcia – and its dogs – was the first to be ‘swept’. The outer inhabited islands – Peros Banhos, Salomon – followed later. The entire population was dumped on the dockside of Port Louis in Mauritius, the island where they still live.

Despite a British ruling that ‘no journalists shall be allowed on the Chagos Archipelago’, I went there once, illegally, and spent a fortnight snooping around. My visit was in 1985, and it is referred to in the Foreign Office papers – ‘he arrived in a yacht . . . was refused by immigration authorities . . . and sent on his way.’ Like so much else in the Foreign Office submissions, the remarks are not quite accurate.

I did indeed arrive on a yacht, a thirty-foot Australian-registered steel schooner from Cochin, in South India. I first spent ten days on Boddam Island: of all the islands in the Salomon atoll, the one that most obviously had once been populated. It was a summertime idyll – empty beaches and a warm sea – except that I seemed never to be quite alone: a C-130 from the Diego Garcia base flew low overhead each afternoon, its crew taking photographs of what I was doing, which was idly exploring a tiny island, making notes, drawing maps and sketching the buildings.

There was a street of small two-room cottages, a church and a cemetery containing the tomb of a woman named Mrs Thompson who had died in 1932. There was a copra-crushing mill, with rusty cog-wheels and pockmarked boilers and hardwood pestle-and-mortars where the coconut oil had been pressed. Also a small railway for taking the drums down to the pier, which now sagged wearily among a grove of sea-grape trees. Old lighters were still drawn up on the beach, as well as harnesses for the mules which had helped drag the trucks down to the loading stage.

The most prominent building was a rather splendid little mansion, built in what looked like the French colonial style. It had three floors, verandas, pergolas, a garden shed, a lawn. On one wall I found a picture of a pretty debutante from Wiltshire, cut from a 1971 issue of Country Life. There were four yellowed volumes of The Times History of the War, and a copy of Pushkin in German. In the cottages there were dishes and saucepans, toys, rotting bundles of clothes and shoes and outside, in a clucking huddle of excitement at my unexpected arrival, scores of chickens, all with the unkempt look of domestic fowl gone native.

No, these were manifestly not the homes of ‘rotating contract personnel’, whatever the faraway colonial rulers in London might have wanted the Americans and the ‘Afro-Asian community’ at the UN to think. This was an old and long-settled village, and quite a prosperous village too – a community where there had been church services, weddings and burials and christenings, where people had read books, played games, worked and saved and made plans for the future. One of the last, according to a history of the islands (Limuria by Robert Scott), had been a scheme by a woman resident to turn Boddam Island into a free port where trans-Indian liners could call and their passengers be tempted by duty-free crystal and whisky, after swimming with the manta rays in the baby-blue lagoon. It was easy to see the temptations of the place.

After ten days of languor, I decided to head down to Diego Garcia itself. I spent a day and night sailing over the choppy shallows of the Chagos Bank and managed to sneak into the lagoon and moor myself among the warships and the atomic submarines. When the British immigration officers discovered me, they were furious: they had in their briefcases faxed copies of letters the Foreign Office had written to me two years before, formally refusing me permission to come, and now they waved them at me and insisted that I leave.

But my skipper, a tough young Australian woman, drily informed the immigration men that she was claiming the lagoon as a ‘port of refuge’, as was her mariner’s right, and that she would be staying on Diego Garcia for at least the next two days. And so we dropped anchor; there was nothing the authorities could do as international maritime law prevails even in Diego Garcia.

The Americans were friendly enough. After the British officials’ boat had burbled away to the shore, some of the crew of two American ships – the command ship La Salle and the atomic submarine Corpus Christi – came across in their liberty boats, took us aboard and showed us around. Inside the atoll lay an armada that made Pearl Harbor look puny. Dozens of supply ships rode at anchor, their decks loaded with tanks, rockets, trucks, earth movers and fuel bowsers, each ship judiciously separated from its neighbour by a space known as the ‘explosion arc’ in case of accidental detonation. There were frigates, destroyers and marine carriers. All kinds of aircaft landed and took off from the runway: fighters, bombers, fuel tankers and tank killers. It was a relief to put to sea again, into the thousands of miles of empty ocean which come between Diego Garcia and any of its potential targets on land.

I have never been allowed back: when I applied to go there legally in 1993, permission was refused by the Foreign Office in London.

The closest I have been to the islands since is Mauritius. There, late last year, I met a woman, Rosalyn Rabrin, who for almost thirty years, since she was ten years old, has lived in a windowless tin shack in a shabby area of Port Louis called Cassis. The shack measures twelve feet by fifteen, and, when the Mauritian sun beats down, is insufferably hot. She lives with her husband Rosemont, a casual labourer on the docks, and their four children – two of whom, fifteen-year-old Sharma and eleven-year-old Martina, were with her on the day we met. The living space was entirely taken up with two beds, a chair and a wardrobe (there was no room for a table): there was a single light bulb; and when the family eats, or when the children do their schoolwork, they do so outside, on the packed dirt of the yard.

Mrs Rabrin is, by law, by birth and by choice, a British subject. She and her children have passports that declare them to be, just like Gibraltarians or St Helenians or Anguillans, British Dependent Territories Citizens, a curiously British underclass of citizen (by contrast all citizens of French possessions are fully French) who will possibly be – one day – legally able to live full-time in Britain: the House of Commons is still considering this idea. For now, though, she lives in the same shack that accommodated her when she arrived in Mauritius by ship from Boddam Island.

She grew up in the narrow street of two-room cottages I had seen, and she remembered it well. There had been a shop, which was open once a week. She showed me a snapshot of the church, and another of the manager’s house. She remembered watching the men harnessing the mules to pull the oil barrels down to the quay. She and her girlfriends, who went to primary school on the island, used to swim beside the lighters as they pulled out to the oil ship anchored in mid-lagoon. The vessel was invariably the Zambezia, which could reach Mauritius in four days, and sometimes, she said, took passengers. More often the boat that took men back and forth to Port Louis was the Nordvaer, or a smaller craft called the Isle of Farquhar, which did a three-monthly supply run to all of the islands.

She also remembered the day the villagers were rounded up and told they had to leave.

It was in the summer of 1971. The previous September a Foreign Office official had written an order for the islanders to be deported from their own homes, and had written an Ordinance – no parliamentary approval needed – that sought, among other things, ‘to maintain the fiction that the inhabitants…are not a permanent or semi-permanent population’. The government had decided first to cut off the islanders’ employment: for £1 million they bought out the islanders’ sole employer, the Chagos Agalega Oil Company, and formally closed it down. She remembered the officials who arrived on the deportation boat that summer morning bringing pieces of paper which they gave to the adults: no doubt these were copies of the Ordinance under which the removal was to be accomplished.

‘We were told they were going to close down the islands,’ she told me, her rapid Creole translated by my taxi driver. ‘I am not sure what I thought. My mother and father were quite angry, I remember. We got our stuff from the house, and we were put on the boat by about evening-time. We were sealed down below, in a big iron hold. They put the horses and the mules on the deck above – I remember the terrible noise they made, clattering about up above.

‘We had dogs, but we had to leave them behind. I was very upset. I didn’t know why we were being taken away. No one had done anything wrong. Everyone was still working – they had been crushing oil on the very day we were ordered on to the ship.

‘We left after dark, so I can’t remember seeing anything. I don’t think there was a porthole, in any case. It took three days to get to Mauritius. There was nothing to eat, and very little to drink. I remember people squeezing flannels and cloths to get rain water to drink. It was terrible. And then we arrived at Port Louis, and someone gave my father some money, and we were told to find a home. And that was that. We never felt the people here wanted us. My father never had a proper job. We’ve never fitted in.’

I asked her if she wanted to go home. I suggested that she now lived in a city full of possibilities – for her daughters, at least, if not for her. Back on Boddam Island there was nothing. Just ruins. Did she really want to go back?

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘Without any doubt at all. Maybe not to stay forever. But we all want to go back. It is home, even if it is a simple place. I want to see it again, and remember. And our children want to go too.’ The two girls nodded their heads in vigorous agreement. ‘No doubt at all,’ said their mother. ‘We want to go.’

At the time I asked the question it had suddenly become – at long last – a highly pertinent enquiry. Because in 2000, after three decades of legal wrangling, it was finally beginning to look as though the islanders might be able to return, to reclaim what they lost when the British government decided forty years ago that ‘no indigenous population shall remain’ on the islands of the archipelago.

The plight of the people whom the Mauritians call ‘les Ilois’ has received only scant and intermittent attention over the years. The Washington Post first broke the story in 1975, when a reporter visiting the island heard about 2,000 British subjects who were mysteriously penned up in a slum near the docks. (News of the various British proclamations and ordinances pertaining to the islanders was always shielded from the British public by being published only in the BIOT Gazette, an official government publication of necessarily very limited circulation.)

I followed the story up – I was based in Washington at the time for the Guardian – and found out that Britain had managed to conceal the $14 million it was paid for the fifty-year lease on the islands by persuading the Americans to disguise the cost as a discount on the research and development charges for a new generation of Polaris nuclear missiles then being sold to the Royal Navy. There were desultory congressional hearings in response to this revelation. Senator Edward Kennedy referred to ‘a clear lack of human sensitivity’; the New York Times made much of how ‘depressing’ the story was ‘for anyone who wants to believe in the essential decency and honesty of the British government’; and a film was made and shown on British television which used original Central Office of Information black-and-white footage from the 1950s showing the undeniably settled condition of the locals, and their state of impoverished happiness.

But little else was done. The British paid out £4 million as compensation to the islanders in the mid 1980s when it was politically appropriate to be seen to be doing something. But there was never any mention of the possibility of their being allowed to go home. The US Airforce flew a group of defence correspondents – who must be among the most malleable and cravenly respectful of all journalists – to Diego Garcia for just five hours to report on its technological wonders. ‘The Malta of the Indian ocean,’ wrote one. ‘A place of incalculable strategic significance,’ said another.

And that, essentially, was how the status quo was quietly maintained for thirty years. However unfortunate the islanders may have been, however shabbily they may have been treated, their grievance and exile were insignificant when set against the military needs and security of the West, and particularly the US. Or to put it another way: the end, in this case, amply justified the means.

This smug quietude – much cherished by the British Foreign Office and the Pentagon – was shattered last year when Olivier Bancoult, a mild-mannered, middle-aged islander who now works for the Mauritian Electricity Board, won leave – and British legal aid – to fight a case against the British government. He made the claim, in particular, that Section 4 of the BIOT Immigration Ordinance of 1971 – the order under which the islanders were removed – was illegal. The Ordinance states baldly: ‘No person shall enter the Territory or, being in the Territory, shall be present or remain in the Territory, unless he is in possession of a permit or his name is endorsed on a permit…’ The fact that ‘no person’ meant in this case ‘the inhabitants’ of the islands struck Olivier Bancoult as manifestly unjust: it meant that the law, as in medieval times, had allowed people to be expelled from their own country. Surely, he sought to say (and had the British taxpayers’ money with which to say it), it ought not to be.

The case was fought by the noted South African barrister and civil rights champion Sir Sydney Kentridge. Bancoult’s solicitor, Richard Gifford, was from the firm of Bernard Sheridan, a lawyer who has himself long been interested in the plight of the islanders. Few at first thought the court would permit the case to proceed. David Pannick, the QC engaged by the Foreign Office, made many persuasive arguments about the need for the case to be heard by the Supreme Court of BIOT – comprising a semi-retired judge who lives and holds court in Gloucestershire – and not the High Court.

But in the end the High Court did agree to hear Sir Sydney plead Bancoult’s case – and on November 3, 2000, Lord Justice Laws and Mr Justice Gibbs reached an astonishing verdict. Citing the Magna Carta and its ancient provisions about the illegality of deporting any man from his own home, the court unanimously decided that Section 4 of the BIOT Immigration Ordinance was unlawful, that it should be quashed, and that Mr Bancoult and the islanders who were now living, like Rosalyn Rabrin and her neighbours, in the slums of Mauritius and the Seychelles, should in consequence be allowed to go home.

The British Foreign Secretary, Robin Cook, announced that the government would not appeal against the ruling. Later the same day, the Foreign Office published a new Immigration Ordinance which confined the banning order only to the island of Diego Garcia itself. For the rest of the Chagos Archipelago, anyone who held a British Dependent Territory Citizenship passport because of his or her connection with the islands could now go and come as he or she pleased. Mr and Mrs Rabrin and her children, in other words, may now go back home to Boddam Island. They can go to their little cottage, reopen the shop, clear the garden at the church and weed old Mrs Thompson’s grave, and stay where Rosalyn herself was born, for as long as they like.

As I write, the whole subject of the British Indian Ocean Territory is awash in a sea of complications and recriminations. The British are shamed and embarrassed. The Mauritians are bewildered. And the Americans, not entirely unreasonably, are furious. The Pentagon, after all, had accepted in good faith that the British had entirely ‘sanitized’ the archipelago and that it would remain so until the US lease on Diego Garcia had expired.

Eric Newsom, the US Assistant Secretary of State for Political-Military Affairs, wrote to his equivalent in the British Government last June that settlements on the outer islands ‘would…immediately raise the alarming prospect of the introduction of surveillance, monitoring and electronic jamming devices that have the potential to disrupt, compromise or place at risk vital military operations’ conducted from Diego Garcia. Terrorists could operate from within the territory.

For the first time in the history of our military co-operation on Diego Garcia, significant personnel and other assets would be required solely for the purposes of protecting the forces, materials and facilities located there. Initiation of such requirements on the island would, beyond the considerable expense for both of our governments, possibly entail reconfiguration of the base facilities…

No American officials have spoken since about the problem thrown up by the court verdict. It was mentioned in only the most perfunctory manner by the newspapers – last November they were much more concerned with the US presidential election. I was in Mauritius at this time and there met an American naval officer who spoke disdainfully of ‘that Mickey Mouse court’ in London, and the ‘total irrelevance’ of the judges’ decision.

We were having the conversation on the Port Louis dockside, watching a large American logistics ship, the USS Bob Hope, dock with 500 sailors on leave from the base. No, he said, no one would be going back, not to any of the islands, so long as there was any American military presence on Diego Garcia. Given the state of the world, he added, that was likely to be for a very long time.

According to Olivier Bancoult and his lawyers – and to what British diplomats are now saying privately too – Americans holding such views are going to be sorely disappointed. For islanders will be going back to their islands, and very soon. The consequences could be extraordinary. The population of Chagos Islanders in Mauritius and the Seychelles is believed to have grown to about 5,000 adults and children. If many of them return, a whole new colony will need to be created. In a strange revival of Victorian imperialism, Britons will have to go out to Boddam Island and to Peros Banhos Atoll and build things: an administration building, a small network of roads and sewers, a police station, a court, a school, a small cottage hospital, a radio station – all so that the returning islanders can have the basic services expected by British citizens. There will have to be employment, too – maybe copra or coconut oil; or – most keenly supposed – tourism.

As I write, the Foreign Office is said to be ‘studying all possibilities’.