I see the woman dodge into the shop and know her immediately. Mummy and Daddy’s friends them, have all vamoosed, but me, I will never forget them. Mummy used to say I have bad heart because if you do me bad, I do you back, God no go vex. And this woman, she did me and Mummy bad. Common shop cannot hide her keep. If she likes, she should run to Kafanchan today, me I will follow her in her back-in her back.

Her name is Mrs Mbachi, Mama Ujunwa. Me and Uju, her last-born, used to be friends before-before. Mrs Mbachi them would come to our house, she and her husband. I don’ know his name. I use to call him Uncle or Papa Uju. He like to drink Seaman’s Aromatic Schnapps and pour libation on the carpet because he carries chieftaincy title. Mummy would boil and mud her face, frowning. After they left, she made Mercy, our housemaid that time, to scrub the carpet with Elephant Blue and brush. She used to point in Daddy’s face with her yellow fingers like uncooked shrimps: ‘Bia, this man, don’t be bringing these bush people to come and spoil my Italian carpet for me!’ And Daddy would throw his head back and laugh because he liked when Mummy does as if she is scolding him, even though they are always doing love. Daddy would pinch her cheeks and call her ‘Ikebe Super’, his hailing name for her because he said he can perch on her bum-bum and she will just be walking and not know he is there. Then he will beat her on the thing, kpaa!, like that. Mummy will pretend to be vexing until he drops something for her, and I knew I was getting a new dress and shoes and bag to match after escorting Mummy shopping to spend the money, and maybe even Den’s Cook for hamburger and ice cream for me and cream soda for Mummy. Mummy will tell them not to put tomato o, because I don’ like tomato and they will say, ‘Madam we know noooow,’ and she will dash them money too because they behaved well to remember what me I like to eat.

Those were the days when things were sweet.

When we came back from eating his money, Daddy will now put turntable and play William Onyeabor ‘When the Going is Smooth and Good’, and he and Mummy will dance and dance, but I dinor know that something like that song is singing can do us as well.

That time, Mama Ujunwa used to give my mother cloth on hand, and she will pay after – George and Georgette and Akwete and plenty-plenty Hollandaise – fresh from Main Market in Onitsha, before any of the wives in our side had them. After Daddy died, she was among the first to come and collect her property back. I didin even see her at the burial. That’s why she is hiding from me inside the shop like a rat in a food store.

I leave where am squatting and pursue Mama Uju. She enters a jewellery shop in Ogba Gold. I know this shop. Mummy used to come here before, when Mama Uju introduced her to Solo, the owner, because he don’ cheat since he is a church person and can swear on Bible. Inside, all the showcases are lined with black foam so that the rings, earrings and all those assorted things shine like stars in the night sky. Mummy used to buy gold, not GL, as she told anyone who asked, but I don’ know what is different between gold and GL. It don’ matter anyway. The whole thing is gone now, plus-including her wedding ring and the small ring made from Igbo gold that I used to wear when I was small. It’s in all the pictures. Those ones too are gone, the albums and frames. Daddy’s brothers took them. What is their business with pictures they are not inside?

Am leaning against the zinc walls of the shed, and people are looking at me with corner-eye but nobody chats to me, not even small ‘How are you?’. My silpas are too big. Aunty Ojiugo said it is better to be big than small so that I will wear it a long time. The sun is entering innermost my eyes. It’s afternoon. My eyelashes divide the colours into red and green and yellow and orange but me, am not going to find shade where will cover me. Let Mama Uju come and pass. I want her to see me here. I want to see the thing her face will do.

A mineral seller plays bottle music with his metal opener, sliding it across the red Coca-Cola crate on his head. Some of the bottles are empty. The others are black like heaven, sweating with cold. There are also Krest bitter lemon and the tonic water my mother used to sometimes drink, that tastes of malaria medicine. The soft drinks are what carry Mama Uju’s legs out of the shop. Always a longathroat, this woman.

‘Hey, mineral-person! Come!’ It is her voice.The man stops and turns back. He don’ even give me face and maybe that’s what makes Mama Uju think that me I’ve gone. She steps out. ‘You have soda water? Is it cold?’

‘Aunty, good afternoon,’ I say.

‘Jesus!’ She jumps. The mineral seller shows me warning with eyes not to spoil market for him. Mama Uju comes back to herself. Her chest is going up and down, up and down, like a dog that has chased its tail tired.

‘Treasure? Is that you?’ That is the name that everybody uses to know me because of my daddy.

‘Yes, Aunty. Is me.’

She holds her throat as if her heart is jumping out of it. Her hand is full of chains and gold rings. When I was small, Mama Uju was black. Now only her hands and feet are remaining that colour. Her face is fair, but it’s not fresh like Mummy. Mama Uju’s yellow is forcing-yellow, like a mango that has been tied in a waterproof bag to ripe it quick before selling. Her cheek and eyelids have drawn red-red threads inside. She is wearing a blouse that sits on her shoulders, orange lace. English lace. The space between her breasts sparkles with sweat. There are hairs there and under her chin. Everybody knows only wicked women like Mama Uju have beards like men.

‘Hewu! You poor child. How is your mother? Embrace me.’

‘She is fine,’ I say.

Mama Uju narrows her eyes. She is continuing to open arms to embrace me, but I refuse to move. The mineral-man’s eyes are on her and then me. He hands her a bottle of soda water and also a bottle of tonic water.

Mama Uju waves him away, irritation doing her whole body. ‘Go! Take that thing that is not cold and go.’ She sucks her teeth. ‘Idiot.’ Mama Uju likes doing Big Madam. She thinks if she shouts at people it shows how important she is. She stares at me and I stare at her back and don’ bite my eyes. I know she wants to leave me here and go, but shame is catching her. She shuffles her feet.

I feel like insulting her. I want to tell her the ancient and modern of her life. I saw it all. Nobody here gives children ear, so I saw everything just by being quiet and doing like I dinor see. I saw how she used to sneak eyes at my daddy when her husband dozed on the armchair, blinking like this and that as if there was something in her eye. She is his third wife and the man is old and rich and didin go to school. When they sat down to eat the food Mercy cooked, Mama Uju would use her toes to be touching Daddy under the table.

When Daddy smiled at her, she dinor see that he mercied her, but me, I did. After all, her husband was old and smelled like ogili okpei inside carton, and everybody knew he stored his money under the mattress as per local man, and Daddy was the one that helped him use his money well, like importing and exporting and that kind of a thing.

Anyway, I need Mama Uju to dash me money, so I suck my words and swallow them.

‘Aunty, how is Ujunwa?’ I bend my head to one side. ‘Long time I have not seen her eyes.’

‘Hewu! She is fine, my dear. She keeps asking when she can come and see you people, but she is so busy now, as per secondary school chikito, you know. All those assignments . . .’ She stops talking because she can see me standing in front of her and am not in school. Stupid woman.

‘Do you know where we are living now? I can come tomorrow to your shed and take you to the place. Or now, sef. Did you bring your car?’ I say.

Mama Uju looks around the market for somebody to call her name so that she will now go to greet them and never come back. ‘Ah, my car is in the mechanic, my dear, but I will find the place and I will come, you hear?’

She fumbles in her bag and brings out one ten-naira note like this. It is rumpled and she straightens it, ironing it between her hands.

‘Mummy is not yet well. She sleeps all the time. The other day, she was calling your name – “Nne Uju, Nne Uju” – like that. I haven’t eaten since two days now, and Aunty Ojiugo hasn’t come back since she left for Nkwelle-Ezunanka. You remember Mummy’s sister? Her half-sister. Yes, the one that farms. Her husband don’ want her to see us again.’ I twist my face and my empty hands – the money is already inside my pocket. I see from her eyes, from the way she is looking at her watch, that she don’ want to give me more money and am angry. After all, didin Daddy make them money? He used to gist Mummy what he did for them and me, I heard. Before everything happened, all of them used to come to him as if he was Jesus, now she wants to leave me in the middle of Eke Awka market with only one dirty ten naira that plenty people have touched?

‘Please, let me follow you to your shop and sit for a while, Aunty, the sun . . .’

‘No!’ She clears her throat and smiles. The lines in her cracked lipstick spread. ‘I’m not going to the shop.’

She don’ want me there. Am the daughter of ‘That Man’ and she don’ want people to remember that she knew him. I start crying loudly. People are beginning to look. It takes a few tears before she brings out another five naira. Stingy woman. Mama Uju takes her bag and walks away fast-fast. She don’ even say ‘Don mention’ when I say ‘Thank you’ to her.

I cross from Ogba Gold into Babies and wander among the tinkling toys and tiny clothes. The whole place smells of Tenderly and Pears baby powder. The traders here, they like to rub their stuffs all over theirselfs and be smelling baby-baby. Who don’ like baby smells? Before, when I used to come buying with Mercy, she hated to waste time, so it was put head-come out. Now, am just walking slow-slow in the market, eating with my eyes. Where else am I going today? Mummy is just sleeping sleep all the time. She will not know if me am there or not there.

The matured men and women selling, stare at me and the ones doing boyi for them in their shop, learning trading from the traders, stare too. Nobody walks like I do in Eke Awka, dragging their feet. You can do that in a supermarket with the things arranged fine-fine on shelves, with one door in and that same door out, but not in the market with plenty ways in and out. A man with a ring of powder around his neck uses his eye to poke inside my own. Just as am about to poke him back, I notice one pregnant aunty like this sitting in his shop looking at baby bath. She’s on a bench, in the cool shade. I run towards her, but the man is faster, blocking me.

‘Get out of here,’ he says. I twist my neck around his potbelly.

‘Aunty, please.’ I put my hand to my mouth to act eating like I see the beggar-boys do. ‘May you born boy, a big strong boy. May your house be full of boys.’ The woman laughs.

‘Don’t give her anything. You can’t see she is in school uniform?’ He turns to me. ‘Why are you not in school?’

I want to ask him can he not see that my uniform is too small for my shoulders? I have opened the armpit so that I can move inside it, but it don’ matter sha. The man’s question has nothing to do with the price of garri.

‘You will born plenty-plenty sons, one by one, until your house is full,’ I say. People like sons.

‘And what if I want daughters, nko?’ asks the woman. She is a small aunty, just past ‘sister’ level, wearing a starched boubou and scarf that tells me her marriage is new. Her outfit looks like to-match, one for her and another for her husband from the same cloth. She has a big open-teeth on top and a smaller one below. Her body jiggles like hot agidi jollof. She gives me five naira and I pocket it as well. I sing for her:

‘Your marriage will be a blessing, your children surround your table, you will see your children’s children, so says the Lord of Hosts.’

The woman gives me a packet of four biscuits from her bag. The man shaas me away because he don’ want beggars to think that his section is where it’s happening.

Twenty naira. Allelu-alleluia! I wander around Ogba Cosmetics but the men there are young and are afraiding me with their shirts open at the neck. A lot of them have plenty chest hair and wear chains. Some of them bleach like Mama Uju. One or two have Jheri curls, shiny and bouncy, curl activator melting on their necks. I used to have Jheri curls when I was four. By six, Mummy started plaiting my hair for school – not by herself because she don’ know how to plait hair. She paid someone to come to the house every weekend. By ten years, it didin matter what me I did with my hair. Mummy started sleeping and Daddy was not there to say, ‘Ikebe, ah-ah change this girl’s hairstyle now, has she not carried this for one week?’ Aunty Ojiugo got me that comb that you put razor inside and when you comb, it cuts the hair. She had to use scissors first to get the whole thing down.

The men in cosmetics look after theirself like women to bring women in. They stand at the door to their shops and gossip to one another across the passage, and when girls come, they eat them with their eyes, pulling at their hands, gently-gently. They sing, ‘Ifeoma, I want to marry you, give me your love,’ in case one of the girls is called ‘Ifeoma’. They shout out common names too: ‘Bia, Chi-Chi, come and look at my shop,’ or, ‘Ngozi, I’ve got just what you need.’ Sometimes they pull hard, and someone’s wristwatch will cut, then the girls insult them, but the men like that, so they laugh more. I like the smell of cosmetics the most. There is Cleopatra piled by my elbow, the soap Mummy used to use and baff. I would like to buy but food is greater than Cleopatra.

In Kwata, the meat side, I find intestines. When Daddy was alive, he loved to celebrate by slaughtering animals. A ram for Mummy’s birthday, a goat for mine, a cow for Christmas, which he shared to our neighbours and the less fortunate, the motherless babies and widows them. Now, am the less fortunate and I know that everything is food, is just remains how to cook it. I haggle how Mercy taught me, when the traders would grow saucy and ask why she was being stingy, after all, the money she was saving was not her own. They would ask out of the corners of their mouth, half-joking because they wanted to do customer with her.

Mercy. They came to collect her like property too. The man that came was the same man that brought her to our house. She use to call him Uncle Joe. He was an agent and his job was to be carrying girls from the village to do maid in town. Mummy was not sleeping that time and she begged Joe, that he should please let Mercy stay. She told that man that me and Mercy were like senior and junior sister.

‘What kind of life will she have in the village?’ Mummy asked. ‘Let her stay here, two years she will take WAEC, by then her value to you people will rise. She will be able to do any job she wants, even employ plenty people if she has her school cert.’

I was just looking at Uncle Joe as Mummy was begging, and I could see the begging was sweeting him. His own was just to find houses for the girls he brought from the village and collect finder money, which was already much. Mercy told me that she and her friends thought Uncle Joe used to throw all of them far from each other so that they would learn Igbo fast-fast. The truth was that he did it so they didin talk about how much they were paying them. That was how she saw another of the girls in the market that had left her madam, and the girl told her that Joe was chopping their money and sending kobo to their parents in the village. Chicken change. Mercy reported to Mummy and Mummy now started sending her money to Ikot-Ekpene, cutting Joe out. We didin see him again oooo, until after Daddy died.

After Daddy died, Mummy told Mercy that she cannot pay her until things were better, and Mercy said anywhere me and Mummy go, she will go. That if we are eating palm nut, she will follow us to eat. Until Uncle Joe landed.

‘Dem don already pay bride price,’ said Joe. ‘She be pesin wife. Wetin you wan make I do?’

‘Let me speak to her father,’ Mummy said.

‘Her papa no too wan talk, Madam. E talk say make I return im property with immediate alacrity. Wetin una wan take the pikin do? She no too dey useful to una in town, and the old man no dey chop anything for im hand.’ Joe pulled himself up until his head reached Mummy’s chest, and changed to English. ‘Please Madam, let us not make this difficult.’ Joe looked Mummy inside her eyes as if they were mates. No more bending neck.

I saw Mercy cry that day as she picked up her things. When she came to our house, she only had one waterproof bag with comb, Vaseline, two dresses and toothbrush, but when she was going, her things fulled two suitcases. Mummy really tried for her. This was before the uncles now came to clear the rest of our property and Mummy started sleeping. Before she left, Mercy now blew her nose and washed her face well. She didin want Joe to see that she was crying because he will tell her father. What kind of child was not happy to go back to their parents? Me, I dinor cry. Crying don’ do anything for anybody.

The butcher coughs.

‘Should I tie?’ He puts the intestines for me in a santana waterproof. It is warm and slimy. I ask him to please double-waterproof for me, but he wants to collect money for extra bag, so I leave him and go away.

Someone jams my body, hard.

‘Sorry!’ A group of boys in tear-tear shorts and vests. The one who bumped into me is wearing monkey coat. His arms are bare and thin but strong like a village boy’s. He pulls me up and they surround me, dusting me, brushing off the dirt and animal hair, plus pieces of bone that break off when the butchers chop up the animals into cooking chunks. I push the boys away from me. Their hands are everywhere.

‘Get out from my face!’ I say. They troop off like a swarm of locusts after something to destroy. My packet of intestines is intact, and I pick it up and follow their path into the food section, hills of garri and ground corn in sacks and basins, fine cassava flour for mixing nni oka, fingers of okro, heads of green and ugu. I approach the friendliest-looking seller, a mama that looks as if she will put hand after she has measured out what I need.

It’s after the garri is tied in its bag that I search my pant for my money, but don’ find it. My hand is in my pocket, through the hole, deeper than any pocket can be, and the woman is eyeing me one-kain as if I am doing bad-bad things in front of her shop. Something holds my throat and squeezes it and all the blood in my body goes into my head.

‘Are you buying or not?’ says the mama. I can’t answer her. She takes the black polythene bag and pours the garri back inside her basin, piling it high into a mountain top.

I know when the first tear leaks out of my eyes. I don’ want to cry. I want to look for my money well, but my eyes are not agreeing.

‘Ha! Please leave the front of my shop before you bring me bad market. Did I tell you I am doing salaka with my garri? It’s not for free.’

My body is shaking me. Those boys with their monkey-coat leader stole my money. Where did they follow me from? When Mama Ujunwa gave me that fifteen naira? When the shining pregnant woman dashed me the five naira? It’s as if somebody has cut the rubber holding me and now everything is falling down inside me. Through my eyes-water, I follow the way the boys have gone. Am like a mad person, opening my eyes waaa, looking inside shops and down roads and people are shouting ‘Comot there’ but my money is gone. Soldier ants are stinging me all over my body.

I sit on the floor and wait for the boys to pass again. Don’ thief have the same places they like to go? Agaracha must come back. If I wait, they will return. The ground is wet and muddy even though is dry season. The women here spray their vegetables with water. Carrots are crying like Judas, aṅara and cauliflower heads, round and white like boils full of pus. There in the mud, under the trays of raining vegetables, I finally allow myself to cry, hoping that all the water will hide the ones coming from my eyes. I don’ stay long. Nobody likes idleness. After they check to make sure I am not dying, the women chase me away again. I won’t go home. I find a dry spot around the men selling yams. They are old men with those line-line mazi caps falling over the sides of their faces, weighed down by the ball at the end. They drink palm wine and salute each other, blasting Chris Mba from the radio. They don’ chase me.

The sheds are closing when the feet appear under my nose. Brown, leather ’pons, with the mouth of the shoes pointing to heaven. The man’s hands are long and thin and he’s holding an open bag. I know the smell. It’s ugili. I hate ugili fruit, it’s stinking and only bush people eat it, but my stomach makes a loud noise as if it forgot. I look up into the man’s face. Thin like lizard, with moustache. He chews the ugili and his moustache moves like he has two mouths. He swallows and the ball on his throat moves up, up and down again.

‘If you give me your mgbilima afo, you can have some ugili,’ he says, pointing at my packet of intestines.

When I blink, my eyes click camera noises in my ears. My face is tight-tight from the salt I was crying in my tears.

‘Is there mango there?’ I ask.

The man sighs, disappointed but not vexed. ‘You children don’t know good things.’

‘If you want my intestines, I bought them, seven naira.’ He laughs. ‘I’m not giving you money.’

‘Okay, I want the whole bag of fruit, then.’ I don’ know what me I will use ugili for, but this is business. After much-much, I will see someone that will give me something for it, or I will ask somebody how to bring out the agbono from inside and how to cook it as soup for Mummy.

‘You’re not serious,’ says the man, but I know he will give me. He was the one to ask for trade-by-barter first, and . . . there is something else. He looks straight inside my eyes. Daddy used to look at me the same.

‘Well, do you want this juicy intestine or not? Think of how they will look in your wife’s soup, curled up like shrimps.’ Intestines was what Mummy used to feed our dogs, over-salted so that they would drink lots of water.

The man stops chewing. He smiles and the moustache smiles, but I can’t see his mouth. ‘Ngwanu, bring,’ he agrees. He hands me the bag of ugili and I give him my packet of intestines. One of the fruits rolls out of the bag. I run and pick it up.

Is then that I see his shoes and his feet properly.

‘You negotiate just like your father.’ He tears open the santana waterproof that sees-through, pulls out one pink tube and sucks it into his mouth like supageti.

His feet. They are not touching the ground.

–

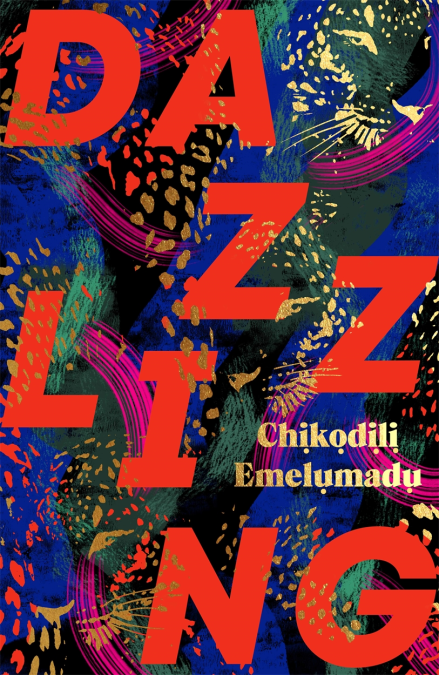

Image © Lucy Nieto