The cow isn’t, for him, a four-legged beast that walks around dreamily, chewing its cud. It isn’t, for him, merely cattle – a source of milk and butter at best, a mooing machine at worst. The cow is his world. She nourishes his body and shapes his character. She gives him an identity and his life a purpose. She is the lens through which he sees the world: believers as friends, others as enemies. The Hindu cowboy accords to the cow the holiest status in his imagination: of mother. It is his duty to protect her honour; it is his privilege to kill for her.

The cult of the cowboy stands on the belief that there’s something special about the authentic Indian cow. It looks different from its Western cousins, with its silky white hide and tall pointed hump. It also boasts the distinction of having been venerated since the second millennium bc. Among the thousands of things Hindus consider divine, the cow ranks high. Cows feature in the life stories of a variety of gods: Shiva, who used one as his personal vehicle; Krishna, who spent his youth herding them; and Indra, who owned one that granted wishes. They regularly show up in texts Hindus consider holy. They also inspire devotion for their supposedly maternal attributes.

The cowboy believes everything that comes from a cow – milk, curd, ghee, urine and dung – is packed with magical powers. He believes stroking a cow’s hump can send a surge of strength through his muscles. The cowboy believes, most of all, in holy war against everyone whose culture approves the killing of the blessed bovine – Muslims, Christians, Hindu outcastes. The cow is for him a symbol not just of Hinduism, but of India itself. He believes the time has come to cleanse the country of cow-eaters.

As the motto of India’s fiercest band of cowboys puts it, ‘To protect our culture and our civilization, we must do as the Vedas say. And the Vedas tell us this – if an infidel kills a cow, we are to pump his body with bullets.’ The ancient texts are unlikely to have issued an order involving the use of guns. What they repeatedly do is rate the flesh of the cow as the best meat known to mankind and mandate its offering to gods and guests alike. But one can either read a multivolume Sanskrit text or put together an army; apparently one can’t do both.

In 2013, Yogendra Arya launched Haryana’s first twenty-first-century militia of gau rakshaks (cow protectors). He also had it registered with the government as a non-profit, tax-free organization. The official logo of Arya’s Cow Protection Army is the gilded torso of a cow flanked first by a pair of swords and then AK-47s. Its slogan: ‘We will keep the numbers of the cow mother intact with our corpses. It’s going to be a fight the enemies will remember.’ The army operates at the level of an independent republic. It has an anthem and a constitution. It also has a fleet of vehicles and a stockpile of arms and ammunition. Its commanders are elected through a three-tier voting process; foot soldiers are chosen through the submission of an application form. Dozens are filed every day. ‘Then we verify their character by enquiries in their villages or neighbourhood. If we are satisfied, we test their skills on the ground for two or three weeks. But most importantly we check their commitment towards the cow mother,’ said Dinesh Arya, the 31-year-old deputy of the senior Arya.

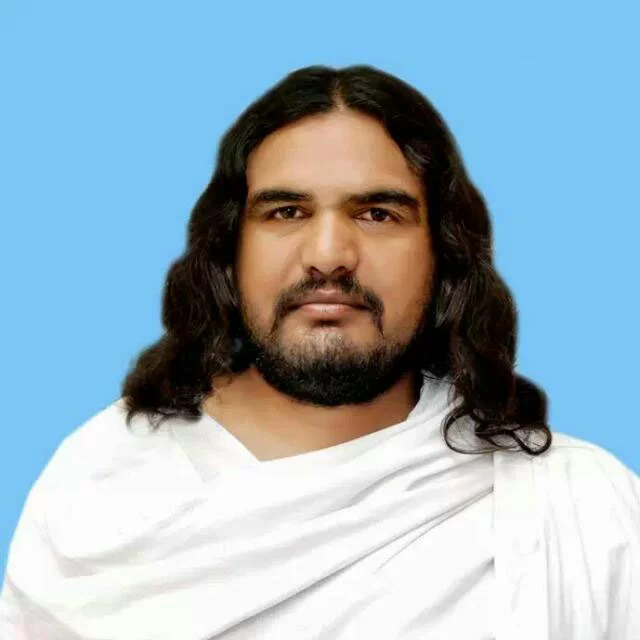

Yogendra Arya, chief of a cow protection militia in the north Indian state of Haryana.

There are various ways to test commitment to the cow mother. One is simply to cross-examine the applicant about the characteristic features of the Indian cow. An applicant may be taken to a cowshed and asked to tell an authentic Indian cow from a mixed or foreign breed. If he is an earnest sort, he could rattle off the list of physical features unique to the native cows. If he’s clever, the applicant could do what a senior cowboy did to impress me on a visit to Haryana: identify a pure and a mixed breed by waiting for them to poop. ‘See, our cows can do it sitting, while the other cows have to stand up to take a dump,’ said Jagdish Malik, pointing to a white-skinned and a brown-skinned cow in the process of defecating. ‘It’s a pity,’ he said, ‘that lying next to our pristine white beauties are hybrids with brown skin and dark spots.’ He blamed the Americans for this unfortunate race-mixing. ‘They smuggled in their cows to breed with ours and undermine their strength and by association ours.’

If an applicant passes through the first level, he is asked to serve the cow mother for a few days: mixing their fodder or nursing their wounds. Their cow cred is vastly improved by the ability to milk one. In the end, though, it’s all about the quantity of cow fluids you are capable of consuming. the measure by which cowboys judge each other. At fifty-five, Kapil Vats drinks a litre of cow’s milk every day. At thirty-one, Dinesh Arya drinks two. The winner is Parminder Arya, a beefy 23-year-old who joined the army in 2013. ‘I drink three or four litres easily. I can drink any amount of milk I am served.’

The cowboy is a rebel

‘Otherwise it would have been the same job-family-kids kind of life. One wants to do something uncommon,’ said Yogendra Arya.

So, at the age of 12, Yongendra left his village and his family and joined a gurukula school managed by the Arya Samaj, a sect of Hindu reformists. He has spent his whole life learning what it means to be a true follower of the Sanatana Dharma, as Arya Samajis call their version of Hinduism. In 2012, Arya was put in charge of the Haryana chapter of Arya Samaj and the manager of its sprawling ashram in Rohtak, a small town in the north Indian state of Haryana. Arya also took over as chief strategist of its cow protection wing.

Early this August, I asked Arya if I could come to see him at the ashram. Gau rakshaks were making national headlines every day. In western India’s Gujarat, some of them had posted a video on the internet that showed them attacking a group of Dalits – outcastes, according to the traditional Indian caste system – for skinning a dead cow. The four young men were stripped, tied to the back of a truck, dragged along for a mile and finally beaten senseless. In the neighbouring state of Punjab, the leader of a cow-protection militia was sent to jail, charged with sodomising a cattle trafficker his men had caught one of their patrols.

Arya was sitting in his office on the morning of 10 August, draped in spotless white cotton and drying his long black hair. At thirty-three, he does indeed have an uncommon life. He is single, lives in an ashram, and leads an army of five thousand soldiers. Arya spends most of his day meeting politicians for patronage and businessmen for donations. In 2015, Haryana became India’s thirteenth state to outlaw the ‘murder’ of the cow and/or the consumption of beef. The state also passed an additional bill aimed at the prevention of trafficking and the conservation of native breeds.

Yogendra Arya speaking at a convention of cow worshipers.

In the evenings, Arya changes into a pair of track pants and a T-shirt and joins his soldiers on cow patrols. He’s addicted to the thrill. The first time he fought for the cow mother was at the age of seventeen. A callow cowboy at the time, he had driven a motorbike to Mewat, a majority-Muslim district in Haryana. ‘I was driving between two villages when I suddenly saw a herd of calves being led by a group of Muslim men. I parked my bike in their path, but they were many, they had guns, and they surrounded me on all sides.’ Arya is the hero of the story and its only witness. He doesn’t win at the end. ‘I ran from there. When I came back with the police, there was not a trace of the cows. The Muslim villagers had helped the smugglers by taking them one by one and tying them up in their backyards.’

It’s a story Arya often narrates to his young colleagues. He told me the reason most young men want to join the cow army is the thrill of combat. ‘They are attracted to the idea of being able to take the law in their hands, to the life of guns and violence.’ A bunch of them live in the ashram at any point of time and follow its routine. ‘Wake up at 4, wash your clothes, join the prayers, lift weights in the gym, eat pure vegetarian food and drink milk,’ said Parminder Arya, the senior Arya’s secretary during the day and bodyguard at night. ‘The life of a true gau rakshak is hard work,’ he said. ‘You know what we do for most of the day – wash our clothes, clean our rooms, cook our food. It’s not what you think.’ I asked why he chose this life when he could be going to college, dating a girl, hanging out at a bar. ‘Any 23-year-old can do that.’ he said. Few of them, I agreed, had access to his kind of nightlife. ‘Car chases, gunfights – people see these things in movies, we live it.’

The cowboy is a special agent

‘Bullets are flying across Karnal every day,’ Dinesh Arya told me on the phone one day, ‘come anytime.’ So, one day in September, I drove to Karnal, a town along the border of Delhi and Haryana, to see the bullets fly. Shortly after sunset every day, the cowboys of Karnal gather at the town’s outpost of the Cow Protection Army – a temple courtyard – sit in a circle, and wait for their smartphones to buzz. One of their phones usually does within an hour. The message is a version of this: ‘Two trucks – number RJ-19 GA0586 and RJ-19 GA5786 – packed with cows left Rajasthan at 5 p.m. Headed to Kashmir. Will enter Haryana in a few hours. Spread the word.’ The cowboys jump out of their chairs and look towards their leader. Sandeep Rana has been the district president of the army for three years; he won the post unopposed. He was the right fit for the job: young, muscular, dynamic. He also takes care of the three cows at the temple and drinks a litre of milk with every meal. The boys look up to him. So do men way older than him. The logic, he tells me, is simple. ‘You are son of cow, I am son of cow. You may be older than me but I am older son of cow so I am like your older brother and you have to listen to me.’

It is Rana who takes a long and hard look at the alert and makes the plan for the evening’s patrol. He divides the young men into three groups and assigns each a different role in the patrol fleet. The first group to hit the road is usually a pair on a motorbike. They have the critical task of timing the appearance of the enemy vehicle, laying out a mesh of nails to puncture its tyres, finding a tree and huddling behind it with a rock in each palm. The second level is those in charge of the real action. They are usually in a jeep, with Rana in the front seat. It is these men who confront the enemies after they have been ambushed. ‘Both sides open fire,’ said Rana. ‘Mostly, both are using local, handmade guns. We also carry other weapons: rods, chains, cricket bats.’ Injuries are expected; they are, in fact, prized. A bandage across the hand counts for one star, one around the forehead no fewer than five. The third and last line of the patrol is the one trusted with emergencies. The men wait in a closed vehicle parked far enough from the main scene of action to be spared the flying bullets and close enough to rush to the front line in case of a rout.

On the days they receive no intelligence, the cowboys carry on with the same routine, but with a twist. As they patrol the highways of Haryana in their jeeps, they are supposed to look at the back of every passing vehicle to see if they are carrying a bundle of cows. It calls for a mix of investigative abilities and lack of irony.

Most cowboys learn the tricks as part of their training. They learn, first, about the make of vehicles – large boots, high backs – that can accommodate the hefty beasts; then, they memorize the brands of jeeps and trucks to watch out for (‘Mahindra Maxi, Tata 407’). There are ways, I am told, of knowing whether a Tata 407 is carrying a cow or simply chairs. ‘The vehicle moves a bit oddly if there are cows inside. We also keep our noses alert for the stink of urine or cow shit – or deodorant, because the smugglers spray it around the vehicle sometimes.’

Since it began its operations in 2013, the Cow Protection Army claims to have captured hundreds of cattle smugglers – including those among the Haryana police’s ‘Most Wanted’ list. But if you asked Yogendra Arya about his biggest achievement in life, he would tell you it’s to have reduced the flow of funds to Islamic terrorists. He claims he has done so by making a dent in the ‘150,000 crore rupees that Indian Muslims make from the sale of cows to international companies making leather shoes, companies which ultimately channel their profits to terrorism campaigns against India.’ This is what cowboys across the country believe when they catch a Muslim travelling with a cow – dead or alive, sick or healthy, bought or stolen.

Sometimes, it doesn’t even have to be the whole animal. The most dreadful act of violence committed in India in the name of the cow was carried out on the suspicion that a Muslim family had beef lying around in its refrigerator. Minutes after the rumour was announced on a temple loudspeaker, a Hindu mob in Dadri, a village in Uttar Pradesh, stormed into the house of the suspect – a 52-year-old farm worker – and lynched him.

‘The way some gau rakshaks have behaved is unfortunate,’ said Dinesh Arya, referring to the incidents of some of his own trainees thrashing the traffickers or feeding them cow dung. He does see, however, their reasons for ‘getting carried away’. ‘If you are not allowed to punish the traffickers sufficiently,’ he argued, ‘how can you stop them from messing with the cow mother again? You have to establish fear in their hearts.’

The cowboy is a husband

For the first few months of his life as a card-carrying gau rakshak, Sandeep Rana didn’t exactly explain to his wife why he came back home so late. All he asked of her was that she open the door for him when he did and serve him dinner. One day he showed her a video on his phone in which he and his men were holding a battered man by the collar while a cow mooed in the background. As she stood there horrified, he told her that fighting for the cow was equal to fighting for the country. He also described to his ten-year-old daughter why the cow mother was in danger, and why it was incumbent upon men such as him to save her. They were proud of him. The wife prayed for his safety; the daughter for his strength. ‘Papa, did you catch a mullah today?’ the kid asked him if she happened to be awake when he got back home.

The wife and daughter were waiting for me in the temple courtyard in Karnal. Rana had sent for the family shortly before my arrival, in a moment of cold terror. He has never had a conversation with a woman with an uncovered head; he has hardly ever spoken to a woman outside of his family. For the following two hours, he left me with them as he took care of the logistics for the evening patrol. The wife and I immediately bonded over the idea that husbands are strange people.

She has been married to Rana for twelve years. They have been good years, she told me, despite the initial culture shock. In Uttar Pradesh, where she grew up, she had freedom: to wear what she liked, watch movies, stay away from the kitchen. In Haryana, where she will spend the rest of her life, she must cover her face and cook for a joint family of twelve. It’s a match her family made for her and she’s glad for it. Rana, she told me, is a good husband. He cares about her, cracks the best jokes and knows how to chop onions.

For the first seven years of their marriage, he drove transport vehicles for a living. Then he dived into this business of saving cows. The job suits him, she thinks. It gives him an aura of authority. ‘People listen to him. They respect him.’ With every passing day, his feelings for the cow mother become stronger. For some years now, he has begun the day by gulping a glass of water mixed with a spoon of cow urine. He has also imposed the routine on his wife and daughter. She doesn’t doubt for a second the magical health benefits of cow urine, but on some days, if he isn’t looking, she makes do with a plain glass of water.

The hardest part about being a gau rakshak’s wife isn’t, however, the compulsion to partake of cow products. It’s to know that if you happened to be in a sinking boat with a cow and he could save only one of you, he wouldn’t even have to think. Great men put their goals before their families, he often reminds her. ‘If Bhagat Singh had been made to choose between the nation and the wife, India would never have won its freedom.’ Behind every successful gau rakshak is, apparently, a patient woman. He has never taken her to the movies. ‘Give me the twenty rupees you will waste on a ticket,’ he tells her, ‘and I will show you a better video on my phone.’ After all, a video of a cow patrol packs in all the elements of a Bollywood movie: emotion, suspense, action. He hasn’t taken her to a restaurant in at least five years. The same goes for shopping.

Four hours after I arrived in Karnal, the Rana family set out on their first family outing in years. Rana dusted off his old car, fixed its engine, ordered everyone in the courtyard to get in – the wife, kid and me in the back seat; him and his right-hand man in the front – and rolled it out for a long drive. He was taking us on a personal tour of cattle-trafficking shortcuts between Haryana and Uttar Pradesh. He announced his two-in-one plan on the way out: ‘You will see how they manage to outwit both police and gau rakshaks, and the family will get some fresh air.’ For the next hour, the car squeezed its way through some very narrow dirt tracks lined by wheat fields on either side. At the end of the stretch, the farms ran into a dense row of bamboo bushes. On its other side was a riverbank: a platform of sparkling white sand sloping down towards a thin stream of water as blue as the sky.

‘This,’ Rana said, as he waved his arm around the scenery, was ‘ is the territory of the battle over the cow.’ This two-hundred kilometre stretch of the Yamuna tributary marks a border between Haryana and Uttar Pradesh – a separation more cultural than physical. The former has a large population of Muslims and Dalits, the latter many of India’s vegetarians. Haryana is governed by a political party committed to the interest of Hindus; Uttar Pradesh by one that depends on the electoral support of Muslims. ‘Only those with a foolproof plan dare to carry cattle through the official highway between the states, said Rana. ‘The others drive through the water.’ On most nights, gau rakshaks wait for them behind the bushes.

Between group photos, Rana showed us signs of the nightly battle: a patch of grooves, a trail of tyres, a bullet hole through a leaf.

No one utters a word as we walk back to the car, except the child who needs no further proof that her father is a superhero. We leave behind a few villages before the wife speaks, ‘Do you really do those dangerous things every night?’ Rana smiles at her in the driver’s mirror as he answers: ‘I hang between life and death as you blissfully sleep every night.’

The cowboy is (in his eyes) a complete man

A complete man is what Sachin Ahuja would like to be called. The 26-year-old sees himself as the face of a new generation of gau rakshaks. He is more Mercedes, he tells me, than Vespa. I see it. His muscles bulge under his tight black T-shirt; he has dark glasses on well past sunset. I am back in the temple courtyard, waiting for Rana to put together the evening’s team for the patrol. Ahuja is the first to show up. One of the things that make a man complete, he tells me, is the ability to divide his time. From 9 a.m. to 6 p.m., Ahuja sells insurance schemes; from 7 p.m. to 8 p.m., he pumps iron; and from 9 p.m. onwards, he responds to the call of the cow mother. His evenings have always been driven by a bigger purpose. At sixteen, Ahuja joined his neighbourhood’s chapter of the Bajrang Dal, a militant organization of Hindu youth. He has since stood for every social cause he’s found worthy, from blood donation to the campaign against ‘love jihad’, the theory that young Muslim men are putting on pricey hair gel and wooing Hindu girls into the Muslim community. ‘It gives a man respect in society,’ he says. ‘People listen to you. You never feel the lack of anything.’ Based on his devotion to the cow mother, Ahuja was put in charge of patrolling the streets in a pocket of Karnal in 2013. He has participated in sixty patrols so far. He has hung between life and death at least once, he claims. ‘There were two trucks full of cows closing in on either side, between them was me on my bike. I escaped at the last second.’

It’s Ahuja who comprises the first line of the night’s patrol on his bike. I sit in the car that follows him. There are five of us in the vehicle altogether – I sit next to a young gau rakshak driving the car; Rana is in the backseat with two others. The rods and chains have been thrown in the boot. At least four other groups of gau rakshaks on bikes and cars follow us on the highway. We are headed to a police outpost that marks the official boundary between Haryana and Uttar Pradesh. All of Karnal’s cowboys have been called in; it’s a special night. Not twenty-four hours earlier, Indian soldiers stormed across the disputed border in Kashmir and blew up a series of militant camps on the Pakistani-controlled side. The cowboys too are itching for some border action. Before we set off on the patrol, each of them had gulped a glass of hot milk. As we tear through the pitch-dark highway blasting Punjabi hip-hop through the open windows, I imagined the milk bubbling in their veins.

A long line of transport vehicles was waiting just behind the police chowki when we pulled in outside. In preparation for the arrival of Rana and company, the Haryana police had put up barricades and cut off all traffic between the two states. Once the entire gang was in, Rana assigned them different tasks for the night: searching the vehicles, interrogating the drivers, keeping track of intelligence. Over the next two hours, a group of Rana’s men clambered on to a procession of trucks jerking to a halt at the barricades and performed the ritual of looking for cows. Every lock was broken, every box torn open. A great variety of things were being moved between Haryana and Uttar Pradesh on this night: apples, onions, soap bars, eggs, petrol. Not one of the trucks had cows.

In the meantime, I sat in the car with the young gau rakshak at the wheel for company. Rana had let me come this far into the operation, but he refused to let me out of the car for fear of flying bullets. Vinod Suryavanshi was by no means dull company. He too felt deeply about the danger facing the cow mother. Unlike Ahuja, the 28-year-old didn’t even have to allot a special block of time for the cause. His day job merely involved sitting in a home-office and lending cash. ‘What do I have to do – give a loan if someone comes to ask for it; receive an instalment if someone pays it on an existing loan.’ The rest of his time is devoted to the nation. He used to be part of a group that went to schools in Uttar Pradesh and spoke to Hindu students about the threats to their culture and identity. This work has been made easier by the internet. He currently manages six Facebook pages and a hundred WhatsApp groups. ‘From 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. I post Facebook updates about the agendas of Islam. Until 2.30 in the morning, I engage with WhatsApp conversations.’ Suryavanshi doesn’t come out on a cow patrol that often; when he does, he doesn’t like to go back home without the material for a week’s worth of Facebook updates.

It is not happening tonight, though. Behind us, Rana and the men are growing more anxious with every passing minute. They are no longer only checking vehicles big enough to carry cows, but cars and even scooters. Everyone is interrogated. Ten hours after driving into Karnal, I have seen neither a smuggler nor a bullet. At midnight, I am dropped at a gas station from which I have arranged for a taxi to take me back to Delhi. The next morning, I call Rana to ask him how the rest of the night went. He tells me it got intense. A crucial piece of intelligence came in just after midnight, he said. ‘It was a Tata 407 and as expected it was taking the river route. We chased it midway through the water. But it managed to cross into Uttar Pradesh – with the cows.’

Photography © Danica