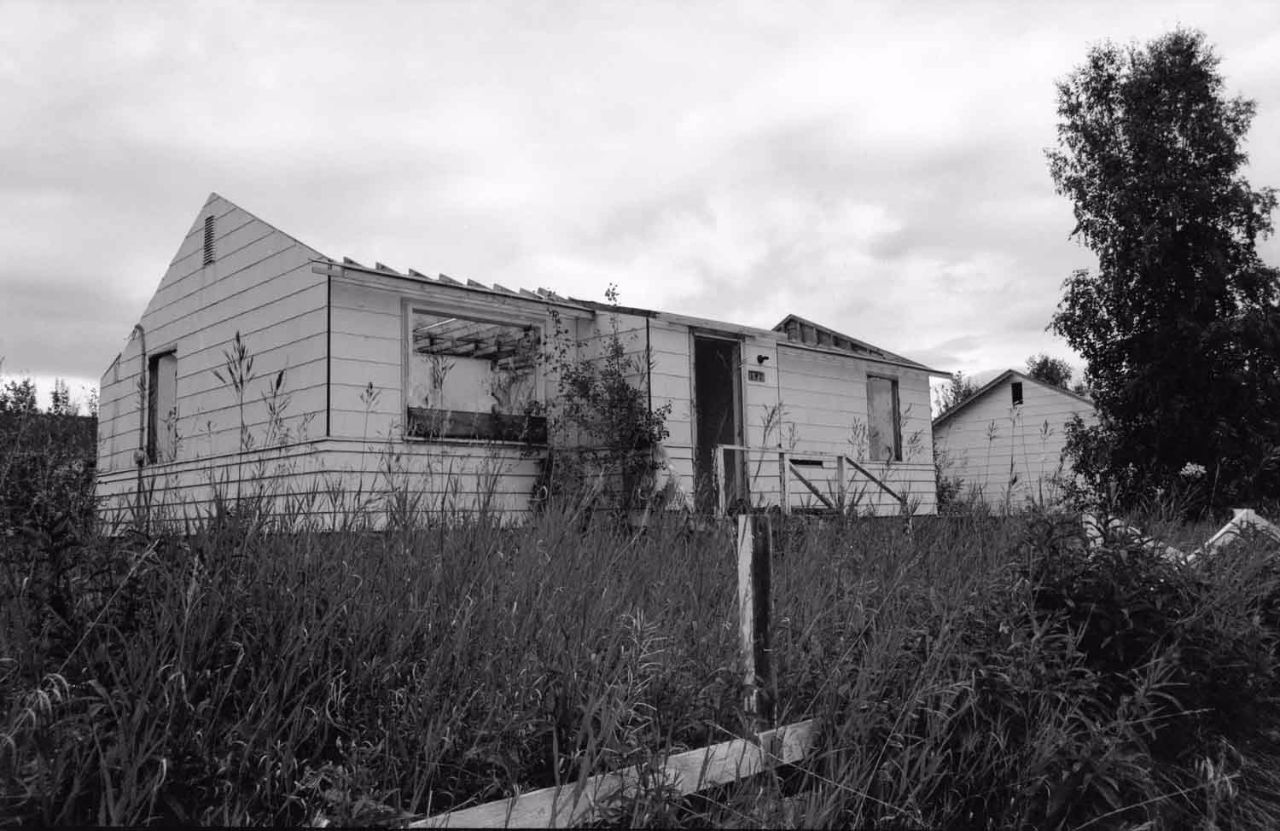

I was standing in front of our old house: 168 Atomic Drive, Uranium City. The street numbers just visible next to what remained of the front door. Up close, our house didn’t seem so ominous, not like the day before when I’d stood on top of the hill across the street and had the sense of being actively warned away. It had been like peering down into a cold dark pool, our house and all the other houses on our street down at the bottom. Now there was just an aura of strangeness – a lingering hint of menace – like a membrane I had to push through.

I noticed things I hadn’t when I’d come back a few days before and seen our old house for the first time in nearly twenty years: the spruce tree with four branches growing out of what used to be the crown; the sidewalk, running up to the side door and then around to the backyard, where it had been devoured by a hedge that once separated garden from lawn and now covered both; the stillness contrasting sharply with the bright fall yellows of the saplings and small trees dominating every yard, their limbs tossing about in the breeze like sea plants writhing on the ocean floor.

Even after five days of entering empty houses, I still hadn’t gotten used to how easy it was, like I still expected someone to appear in the doorway demanding to know what I was doing. I pushed inside, breathing sharply inward as I always seemed to do when I entered one of the houses. Someone had scrawled cunt is good in foot-high letters by the steps to the basement. Rubble covered the floor of what had been our dining room, glittering with glass from the shattered windows. Holes had been punched and kicked into the walls; cupboards, a dishwasher and even a toilet tank had been ripped from their moorings and strewn about the hallway. Here and there touches of familiarity: yellow and black patterned runner carpet covering the steps to the basement where my bedroom had been, wallpaper with yellow and lime stripes on the dining room walls. Normality broke through in unexpected places, patches in a photograph that had mostly discoloured and faded.

Water dripped steadily from the ceiling in the living room, trickling down from that morning’s rain. A mound of grey material on the floor, moulded by the water into a miniature volcano. Possibly asbestos – our house, like most houses built here in the late 60s and early 70s, would have likely been lined with asbestos panelling. Or maybe just some unknown substance, the detritus of modern life as it starts to decay. Wind, rain, snow enters abandoned house so easily, erasing the boundaries between interior and exterior, man and nature. These spaces had a kind of final emptiness, stale air and a cloying, oppressive silence.

In the living room, scrawled over the whitewashed plasterboard:

Moon your cunt is the best I get so mad when guys talk about other girls your cunt is so good I want to fuck you forever . . .

Underneath, a drawing of a woman’s torso with her legs spread, sketched in only a few lines by a surprisingly skilled hand. These drawings, these odes to Moon, decorated every surface in the house.

*

The pilot who’d flown me in, who’d been flying in for years after everything had shut down, explained the vandalism as I was standing on the airport tarmac, waiting for my ride to town: ‘That’s what the kids did here on a Saturday night, hey? Get a case of beer, go to a house with a girlfriend, get drunk, have sex, trash the place.’

I hadn’t been back to town yet, so didn’t understand what he was talking about, didn’t even remember what he’d said until I’d come back to our old house and seen the graffiti on the wall. When I saw the same graffiti in my parents’ bedroom I felt something break; I wanted to get out of town so bad I felt like heading back to the trailer park motel downtown to hide out until I could catch a flight the next morning.

Uranium City had been our home off and on until I was fifteen, when we’d moved south to Vancouver. It was originally a Cold War boom town, a dozen mines springing open in the 50s to fuel the quickly growing American and British nuclear arsenals. In 1959, the American and British governments cancelled their contracts, and all but the huge, crown-owned Eldorado mine closed down. By the mid-60s, the Canadian government had banned the sale of uranium for military purposes, but when they went about developing a homegrown reactor – the CANDU (short for CANada Deuterium Uranium) – and started stockpiling ore for domestic use, Uranium City was on the rise again.

At that time we moved around constantly. My father was a geologist, and his work took him from Uranium City to the Northwest Territories, as far up as the Arctic Circle. When I was very young, we lived near the seaplane base a kilometre outside of town, and the sound of seaplanes, of helicopters, define that part of my life. From there we moved further north, to Great Bear Lake, before settling south in Edmonton when I was four or five. Even after we’d moved to Edmonton, the North continued to flow through our lives in the form of the many northern people who came and went from our house, and the trips my mother and I made in the summer to the bush camps around Uranium City, where my father would be working.

Then, very abruptly, things changed. The mining industry took a hit in the early 70s, and my father’s boss, an old-time northerner named Gilford Labine, went bankrupt and passed away. Without Gilford we’d lost our main link to the North, and work was hard to find. My father was left unemployed while my mother worked full-time at a nearby hospital.

My father changed. In those early years, he’d been home very little. When he did arrive, he seemed like a magical figure, sweeping out of the bush bearing letters written on birch bark, sealskin moccasins with inlaid beadwork, smooth stone core samples lined with veins of silver, copper – even pitchblende. Now he was home all the time. His personality transformed: he became sullen, with flashes of terrifying anger. There’d been signs of this violence before – if I think hard about it, I’d never been entirely comfortable with him. But in those years, he became vicious, even malignant, brooding for days over some fault then lashing out with a cruel, sadistic anger.

My father’s violence had a sadistic, premeditated edge. If he punched me with his fists, or booted me after I’d fallen to the ground, he’d make certain to add some humiliation so that the wounds were psychic as well as physical. Once, he dragged me down the stairs to the basement, showed me some clothes I’d left on the floor, then made me bend over and kicked me repeatedly until I fell, gasping for breath. Sometimes he’d throw money at me and make me crawl on the floor, kicking at me as I picked up the coins as he’d ordered; more than once he banged my head against the wall hard enough to leave lumps and bruises against my skull.

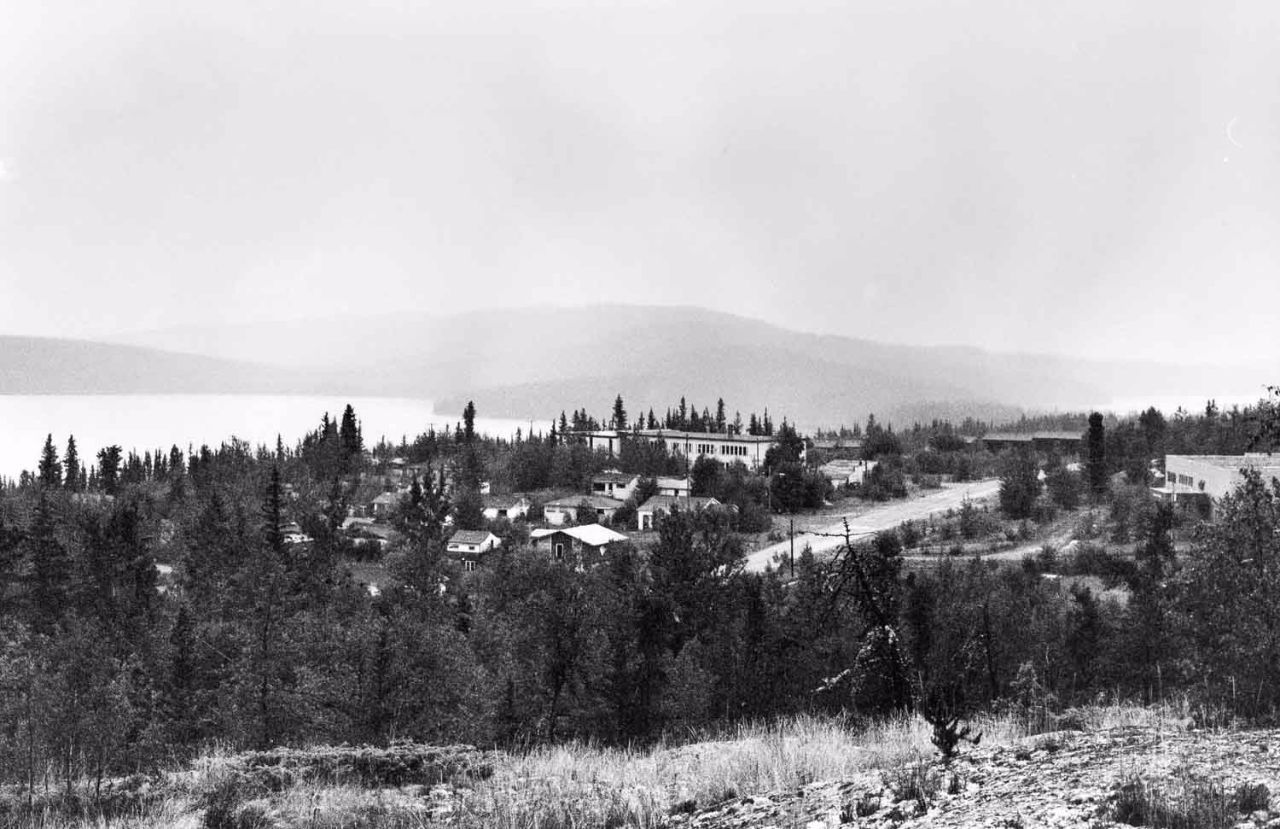

When we came back to Uranium City in ’77, the town was booming again: new houses, freshly paved roads, new businesses and government offices downtown. Foreign markets had reopened, and the CANDU had gone into production. My father had a new job, and the move, while disorientating, was not unwelcome. I was hoping things at home were going to go back to the way they’d been before Gilford had passed away, when we were still connected to the North.

New residents were pouring in; I made friends easily and the town itself was buoyed by confidence – we all had a sense of being somewhere special. Having spent my whole life in the uranium industry, I was proud of the CANDU, and most people in town felt the same way. As far as we were concerned, it was the safest, cleanest and most efficient nuclear reactor in the world. Posters showing how uranium was processed, how the CANDU reactor worked, decorated the high school hallways.

It came as a shock when Eldorado’s president announced that the mine would be closing. Almost up until the day of the announcement the company had been encouraging townspeople to invest in local businesses, building new houses and flying in miners from as far afield as Germany and the Philippines. The news was so sudden, some of the miners heard while waiting for connecting flights in from Toronto or Vancouver. That same president, just weeks before, had assured everyone the mine would be around another ten years at least, more likely another twenty-five. Now they needed to close as soon as possible.

Uranium City was an isolated town, on the wrong side of the inland sea that is Lake Athabasca. The only links to the south were the jetliners flying in and out from Edmonton and Saskatoon, the barges in the summer months and the ice road across the lake in winter, once the ice was thick enough to support vehicles. That winter, it was almost as busy as a southern highway, cars and trucks streaming south and moving vans cruising north. By the time the mine closed its doors in June, the city’s population had dropped by 90 per cent. Without the mine, the town had virtually no economy, and the talk at the time was that it would be ploughed back into the earth. For years, I assumed that was what happened.

My father had mellowed somewhat while we were back in Uranium City, calmed perhaps by old associations and people; we’d almost gotten along for a time. But after the closings we moved south, and he clamped down again soon enough, his savage temper flaring up as it had before.

I left, bouncing between group homes and the street for years before I discovered punk rock and a community of sorts. I moved east, first to Montreal, then on to London and Europe and eventually New York, shifting back and forth every few months, rarely thinking of my childhood.

For most of my adult life I was a chameleon, trying on one role, abandoning it for another, all with a restlessness that propelled me across cities and continents, so that I rarely stayed longer than three months in any one place. I’d worked as a cook, tree-planter, day labourer, film jockey – whatever job I could get without an education. I’d taken on identities – punk rocker, blue-collar worker, boozer – and discarded them just as easily.

I was drunk for eight years, on heroin for a year and a half, had two serious relationships which both ended badly. I’d lived in the moment, swayed too much by wherever I was or whoever I was around to know who I really was.

I’d never found the thread to tie all the facets of my life together until one day I discovered the article that led me back.

It was an old copy of an American outdoor magazine, a journalist describing Uranium City as a sort of Disneyland of ruin: an ice machine in an abandoned curling rink spewing a mountain of ice into the darkness, weeds and saplings growing through the engine blocks of cars and trucks left behind in overgrown driveways. She wrote that residents were scattered all over town, that you could walk for an hour without seeing someone, then stumble on an occupied house where someone waved from a porch; you could jog down Uranium Road – the main drag – in the midnight sun, pausing to peruse the stacks of magazines and newspapers from the late 70s and early 80s stacked in the abandoned houses.

I read the article three times in one evening, amazed that the town still existed, recognizing street names, landmarks, the family names of a few of the people left in town. One of them, an old pilot, had been a family friend back in those early days when we were roaming around the North. I imagined the town perched up there on the edge of the world, empty but serene, like all ghost towns. Even discovering the town still existed was a sort of bombshell: a whole part of my childhood came alive again.

Dimly, almost intuitively, I knew I’d never be able to regain this part of myself unless I went back.

*

As soon as I had the money, I made the journey west and north, catching a bush plane from Fort McMurray to a nearly deserted airport behind the plain that had once held the colossal Eldorado Mine.

When we turned onto Main Street, driven in by the proprietor of the old motel, I knew that Uranium City would be nothing like the article. ‘It’s a hundred times worse than you could ever imagine it,’ the hotel owner said. ‘You’ll never believe what’s happened to this place.’

He was right. Even in the sparsely populated downtown, most of the buildings were empty, windows smashed and doors hanging open, and beyond downtown lay three or four kilometres of houses and buildings that had been abandoned for years, deprived of power or water.

People from town had ransacked the houses for whatever they could find. In a place where the trees were too thin to provide timber, where the most basic supplies had to be flown or barged in, the houses were too valuable a resource not to be utilized. Then there were the kids the pilot told me about, smashing windows, breaking doors, tearing out the innards and scattering them in the weeds and grasses outside. For the first couple of hours I wandered through the town in a kind of daze, up through my old high school, which looked like it had been invaded by an army, and then down to our old house.

What stunned me most of all was the emotion: the houses seemed to radiate not just violence, but also a kind of hate. By the time I found our old house, I felt relieved to see it hadn’t been damaged any worse than the others.

The remaining residents were mostly native, some older whites, one or two of whom remembered my parents. I found a few people I’d gone to school with who’d stayed on, bound by ties of family – or to the land. They flew in and out of the mines south of Lake Athabasca, where temporary camps sprung up when there was work. ‘You don’t even see the houses anymore,’ they’d tell me, and riding around in their trucks, it was true, you didn’t, or at least you saw them differently.

But in the daytime I was drawn back. It was like experiencing two towns, one where life went on, one where it had essentially stopped dead. I began exploring the areas where I had few personal associations, where anonymity granted some distance, and as I became more accustomed to the abandoned areas, I began to feel something beyond violence, beyond hate. Shock, even sadness, as if the houses couldn’t believe their former inhabitants had just left them to the elements. The collective trauma, perhaps, of a whole community that had discovered, very abruptly, that they’d have to uproot their lives.

It wasn’t that the houses were haunted exactly, but the concentration of emotion, dwelling there all those years, had formed a living presence, so I never entirely lost the feeling of being watched, of some set of figures lurking in the shadows, waiting to reappear once I’d left. After a time, this sensation became seductive, even if it felt alien.

Then there was the emptiness. Every house had been picked clean. No artefacts beyond the odd dishwashing bottle, a tattered curtain, and the emptiness that became as much of an attraction as the emotion which lay behind it. I became fascinated by my ability to push through the membrane separating the outside world from the world of the houses, to cross into one and then another, to stride across overturned fences, along barely discernible sidewalks. The stillness, the smell of damp and general decay, contrasted so sharply with the weeds and grasses waving outside. I began to understand something about the kids the pilot had told me about. How liberating it must have felt to kick holes in the walls or destroy some fixtures after having sex on the bare wood floor. A communion, as well as rebellion, a sense of pure freedom.

Yet back in our old house, I no longer felt anything. The rain and the overpowering smell of mould made it feel sordid, even banal. Whatever past I was looking for, I wasn’t going to find it here. The front door banged once, then went still. I looked again at the graffiti. Even the vandalism here seemed to have happened long ago, perhaps in the years just after the mass exodus. The glass shards now worn smooth by the elements, the holes in the walls blurry around the edges. Whoever the couple had been, they were long gone.

I had to leave. Outside, the breeze had picked up, the trees and tall grasses waved in delirious motion, with a sound like the roll of a distant ocean. Empty houses lurked behind stands of swaying poplars, doors were propped open, the windows staring out like eyes from a row of skulls. Entering a neighbour’s house, then another, I tried to remember who had lived where. Fascinated again by the contours of emptiness, how walls between rooms had collapsed, or an exterior wall had been torn away so that the room bled out into the world beyond.

The spidery handwriting, the drawings, leading like signposts from one house to another, up the houses on one block, down another:

Moon . . . Moon . . .

I jumped fences, pushed aside grasses and saplings to clear the way until I was swept into the mania of crossing into the alternate dimension of decay, the same dimension that couple had inhabited as they fucked their way from house to house through my old neighborhood.

*

I walked until I reached the southernmost edge of town. This was the newest part, the part I’d known the least – some of it so new the houses hadn’t been finished when we left. Apartment buildings, two-storey houses, covered in cedar panelling imported from the south – nice enough they wouldn’t have seemed out of place in a relatively affluent part of Vancouver. I’d heard the architect had even won an award for the design. Now, they were just empty. No graffiti, hardly any signs of violence. Doors and windows gone, outlets and light fixtures removed. No emotion, neither shock nor anger. Perhaps they’d been too new when they’d been abandoned, the lives that had passed through too fleeting to leave any trace.

Outside, I heard the sound of banging, coming from a house closer to the lake. Someone taking what they could for their own place. Instinctively I retreated, as I’d been retreating from human contact the whole time I’d been there. I walked until the banging faded into the sound of the breeze, until I was up near the tree line. Here were the best, the newest houses, likely built for management, two, even three stories high, with doors connecting garage and house so the residents wouldn’t have to step outside. However fancy they’d once been, they’d suffered the worst damage of all. Some had been stripped down to barely a skeleton of a house. Others had shifted from their foundations, destabilized by underground streams or the harsh cycle of freeze and thaw, so that they now seemed to stumble into the ground, spilling out an avalanche of walls, staircases, kitchen cabinets and general detritus. Others had collapsed completely.

Even by the standards of the town, they were a bizarre, disturbing sight. The closer the houses approached the tree line, the more they seemed to give up on themselves, as if an army had been steadily lobbing shells from the forest.

The wind picked up and the afternoon sky darkened. Slate-grey clouds rolled in, until it seemed the whole sky was in motion. Drizzle began falling, turning shortly to rain. I sought refuge in a house across the street that looked relatively intact, testing the floor, as I did every time I went into a house, to make sure it wouldn’t collapse. Sections of the walls had been torn away, and as the wind picked up the rain ripped through the rooms, I climbed the stairs to the second floor where the exterior walls still gave shelter.

I made my way into a room where I found a section of interior panelling covered in Star Wars stickers. A single panel, fallen or torn from the wall, lying face up amidst the usual detritus of beams, pink insulation and decaying plasterboard. That fake wood panelling that had been so popular in the 70s covered the interior walls of half the houses in town. Here were Princess Leia, Han Solo, Luke Skywalker, Chewbacca. Must have been a boy’s room, maybe someone a couple of years younger than me, or even my age – though I’d outgrown Star Wars, or at least the stickers, by the time we’d left, they had still been up there on my wall.

I’d seen the film shortly before we moved back North from Edmonton, and it stayed with me in one way or another all the years we spent in Uranium City. I put the stickers on my bedroom wall, on my school binders, and whenever I looked at them I felt like I was with my friends in the Edmonton movie theatre where we’d gone to see the film, in the world of the film itself. Those stickers made me feel protected from whatever lay in this now-alien town, or from the vagaries of my father. When I met other kids in town, Star Wars was my first entry, a shared experience – they’d all seen the film flying down to Edmonton with their families on the flights subsidized by the mine.

Looking at those stickers, those last couple of years took shape around me. An image of our old street, as clear as a photograph, the houses accreting their missing parts, lights burning behind the glassed-in windows. A fall day, as crisp and cold as it was then. My room in the basement, these same stickers on the wall, glancing over them, realizing I should take them down before my new girlfriend came over and saw them, wondering why I still had them on my wall.

During my last year in town, I’d started hanging out with a new set of kids, smoking cigarettes, drinking beer when we could get it, smoking weed. This new direction had opened doors in town that had previously been closed, like my girlfriend: Willow.

I remember going upstairs and peered through the dining room window, looking for her. She usually came down from the apartments on top of the hill where she lived with her mother. They were the same design as the buildings in New Town – as all the houses were in that last phase of development before the mine closed. Yellow poplar leaves on the side of the street, then the blur of Willow’s jean jacket as she descended the rocky hill, tripping down the winding path as sure-footed as a gazelle. She’d been raised in town, had been walking through these hills her whole life. Wolf-whistling through her teeth, as all the kids used to do when they came to someone’s house, our signal so I knew to meet her just up the street.

Even if the old man had mellowed somewhat, I wasn’t sure how he’d feel about me having a girlfriend, especially a girl like Willow. I’d meet her behind one of the giant boulders that must have been dumped on the hill by the glaciers on their long retreat ten thousand years before. She’d be having her first cigarette of the day. Dark hair, dark eyes, small feathered earring in one ear. Cree on her mother’s side. Her kiss tasted of tobacco, the too-sweet Sanka her mother made before she left for work. We’d wait a moment, sharing her cigarette, to see if our friends Sonny and his sister Louise came up the hill from their house around the corner, then up the hill to the plateau where the school lights burned in the gloom across the street, and dozens of kids traipsed in along the Main Road. Cars of the teachers and the older students pulling into the parking spots around the school building.When the snow took over, some of the kids would ride in on their Skidoos. Gathering in the smoke hall at the side of the school, looking for our friends, smoking another quick cigarette before disappearing inside. We’d been together month, and she’d made me feel like I had when I’d been a kid, like I was part of the North again, part of a community.

Back in the empty house the stickers, and the section of wall they belonged to, seemed marooned, plunged underwater. And yet I no longer felt distressed. If I’d come to the end of the line, at least I understood now why I’d come back, what I’d been looking for when I’d first walked through town. Time can decay as well as move forward, but just the act of recalling that memory, that snapshot of myself at fourteen going on fifteen, made the empty buildings seem different, as if I’d stepped outside it, become one of the spirits inhabiting the empty houses. And I could feel her out there in the cold, the wind, almost alive beside me. Maybe she too was one of those spirits, a part of her left behind in the houses. She was here, after all, when everything fell apart, after I’d lost touch with her and everyone else.

I watched the snowstorm out the window, hands thrust deep in my pockets so they wouldn’t freeze. I was wearing only a light jacket, not expecting such cold weather so early in the year. I felt exhilarated. The snow covered everything – the houses, the red and yellow of the poplars, the stands of evergreen rising in formation up the graceful hillside on the other side of the diamond green lake which arcs around the town. It was inexpressibly beautiful, a vision that reproduced all the times I’d looked out on the land in the winters I’d spent there as a kid. Those hills, falling one behind the other all around the town, serene as dormant volcanoes. A landscape that would never change, no matter what happened to the town. The snow had eclipsed the other houses, so they seemed to fade right into the landscape; soon the wind would sweep through all the abandoned houses in town, and the empty spaces would be reclaimed by the forest, the hills, the great sweep of the land.

For a moment, the houses were invisible, and all I could register was the sky overhead, the smell of forest and melting snow, the still green surface of the lake beyond the forest. A flock of geese flew overhead, maybe a hundred feet up, calling as they went, their cries echoing about the streets, the forest, the empty houses all covered now in the same fine layer of snow.