Sorria, sistema: você está sendo HACKEADO! (Smile, system: you are being HACKED!)

Hand-sewn banners; coffins carried upright, captioned ‘Victims of Violence’; hastily scrawled paper posters and thousands of Guy Fawkes masks appropriated from V for Vendetta –

Queremos escolas + hospitais padrão FIFA (We want FIFA-standard schools + hospitals)

The themes were clear and repeated everywhere I turned: no more media repression; no more police repression; down with domination by big business –

Lula, ladrão / o seu lugar é na prisão (Lula, you thief / your place is in prison)

Down with all the old political guard, even the recently revered socialists –

Somos um Rio de sangue (We are a River of blood)

A Babilônia vai cair (e os corruptos também) (Babylon will fall [and the corrupt will fall with it])

Nós não vamos parar – MUDA BRASIL

Amanhã sera maior – MUDA BRASIL

A revolução não vai ser televisionada

O gigante acordou

(We shall not stop – CHANGE BRAZIL

Tomorrow will be bigger – CHANGE BRAZIL

The revolution will not be televised

The giant has awoken)

#Vem prá RUA! (#Come onto the STREET!)

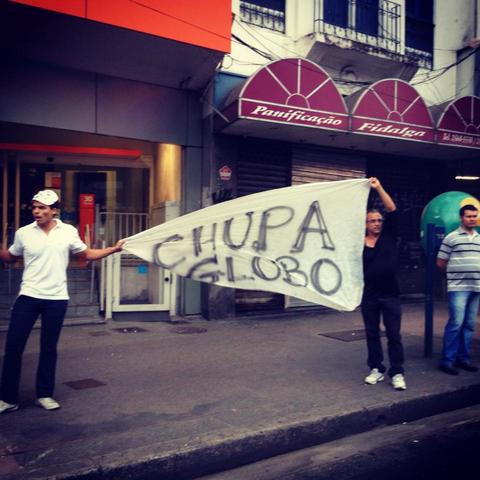

Chupa GLOBO (Globo [media network] Sucks)

It felt as though Carnival came twice to Rio this year.

First there was Carnival in February, as planned years in advance: an extended week of crowded street parties culminating in a weekend of parades minutely and lavishly costumed and choreographed, attended only by those lucky to secure the highly priced tickets, a week that ended docilely in hangovers and municipal mop-ups, remnants of costumes poking out of bins like distant cousins of European Christmas trees.

Then another kind of Carnival struck in June – Carnival by stealth: ticketless, leaderless and limitless, a surge of feeling independent of schools, parties, king or queen; a true subversion of the status quo. A second bacchanal, driven by serious intent.

Living in Rio, as I have been for nearly three years, I had come to think it strange that cariocas are so good at parading – at cross-dressing and cocking a snook at authorities, at pissing on whatever they fancy but also at organizing proper gatherings and even at turning up on time for them with all their Carnival practice – yet they were driving me wild with their lack of complaint. They seemed so passive, so ready to take whatever life and politicians threw at them, be it ever-higher fares for their essential commutes, ever-longer traffic jams, ever-older buses and more dilapidated common spaces, even the particular humiliation of seeing their country suddenly celebrated around the world, while the resulting manna reached only the topmost elites. Where were their standards? Where was their drive? They couldn’t shrug it all off with ‘O Brasil é assim’ (‘Brazil is like that’) forever, could they?

They couldn’t. One more in a string of unseasonal bus fare hikes proved to be the last straw. From 6 June there was a big protest every few days, each bigger than the last and mirrored in yet another clutch of cities. From São Paulo the movement rippled out to include most of Brazil’s major cities and some of the smaller towns in the states of Rio and São Paulo. In Brasília, the federal capital, protesters climbed onto the elegant Oscar Niemeyer roofs of government buildings, populating them with humanity and their direct demands for the first time. Soon sympathetic protests were appearing outside Brazilian embassies around the world.

The protesters’ demands were multiple and multiplying. Naturally they insisted bus fares be lowered. My weekly cleaner Nadir had been paying nine reais each way to travel from her distant suburb into town to work. Within a year, nine became nine-fifty and then ten. She doesn’t earn more than ten times that in a day, so faced losing a fifth of her wage on transport alone. Her case is not only normal but the experience of the majority.

Nadir couldn’t afford to take time off to join the protests – she didn’t even consider it. On her behalf and for all those like her, the protesters demanded more: that the transport companies make their shady accounts public. And that their squirreled-away cash be spent on refurbishing dangerously despoiled health services (Rio has the worst in the country, despite new oil discoveries off the coast boosting the state’s coffers), or on the miserably underfunded schools and teachers (I’m always seeing children playing in the streets and squares in their school uniforms; state schools only take each child for half a day at a time, so they go either in the morning or the afternoon, while the teachers teach both sets, every day), or on the creaking and often murderous state of the public transports system itself.

The politicians who should have been looking after these essentials were pilloried for being more interested in the dazzle of the brand-new Maracaná stadium, all cushioned seats and international sponsorship; for voting through laws that promoted a cure for homosexuality, and constitutional amendments that promised judicial immunity for all sitting deputies, instead of looking into the tiresome circumstances of ordinary services. The colonial-era principle of making surface improvements ‘pro Inglês ver’ (‘for the English to see’, or, these days, ‘for the rest of the world to see’) appeared to be dying very hard. Why am I enjoying wonderful new networks of cycle paths and giggling at teams of new, tourist-friendly, shorts-and-shades-wearing police in the tiny, beach-fringed South Zone (home to Ipanema and Copacabana)? So that no one – no foreigner – will think to notice the chasms in the roads in the extensive North Zone, or the complete absence of train connections and everyday policing in the city’s sprawling West. All these heartfelt complaints found their place on the banners and the digital images projected onto the sides of high-rise blocks that I saw when I joined the protesters marching through the heart of Rio most Mondays and Thursdays in June.

I don’t mean to say that the protests were a carefree expression of anarchy, as Carnival ought to be. I would hate to belittle the anger and the righteousness of the protestors. Yet the serious heart of a Carnival spirit informed the process that impelled people onto the streets, in Rio at least. Cariocas knew what to do when the time came; they weren’t quite so out of practice in holding demos as I had thought.

Now, in August, President Dilma Rousseff has organized some concessions, and the Pope has been to visit. Determined protestors have given way to fawning fans and, as ever, some weeks of rain have damped carioca enthusiasm. That silly constitutional amendment was thrown out but, even at the final vote, some ministers voted for it. No one has yet dared suggest bus fares could rise again, but with the World Cup only a year away and plenty of infrastructure to improve before then, it’s my guess that they will.

All photographs by Nicole Rosner