Early in 1886, Vincent Van Gogh was given a painting task by his teacher at the Antwerp academy. With no money to purchase the required large canvas, new brushes and paint, Vincent wrote to his brother Theo. Theo supplied the materials, and within a week Vincent had painted a pair of wrestlers. He wrote again to his brother to say how pleased he was with the image.

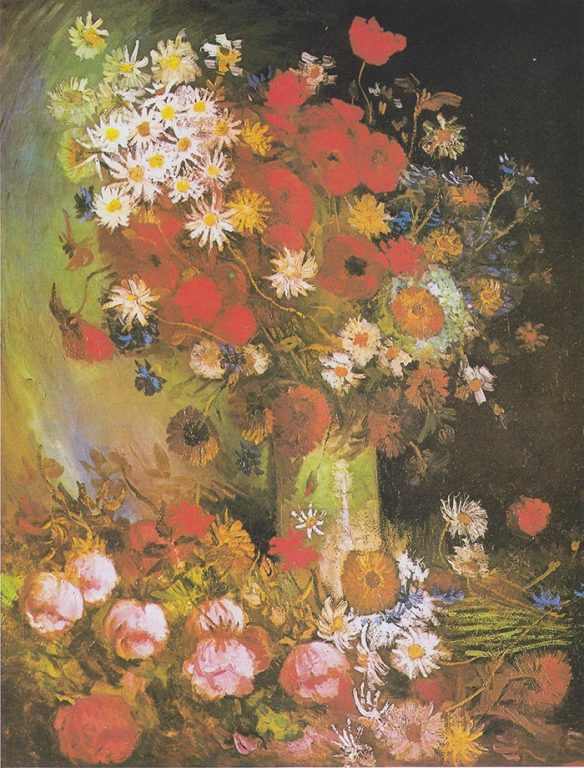

Vincent then moved to Paris, where Theo lived. He took the wrestlers with him, and in the summer, reused the canvas for another painting. Over the human figures he painted a huge bunch of flowers, selected from those that were in bloom: poppies, cornflowers, forget-me-nots, pink roses, larkspurs, camomile, calendula, chrysanthemum, asters, ox-eye daisies and hydrangeas. The large canvas – which he turned, ironically, from ‘landscape’ to ‘portrait’ orientation – presented a challenge: the flowers in the vase were high up, leaving a large space underneath. When he came back to the painting, he filled this space ‘with an opulent foreground’[1] of loose blooms.

Still Life with Meadow Flowers and Roses

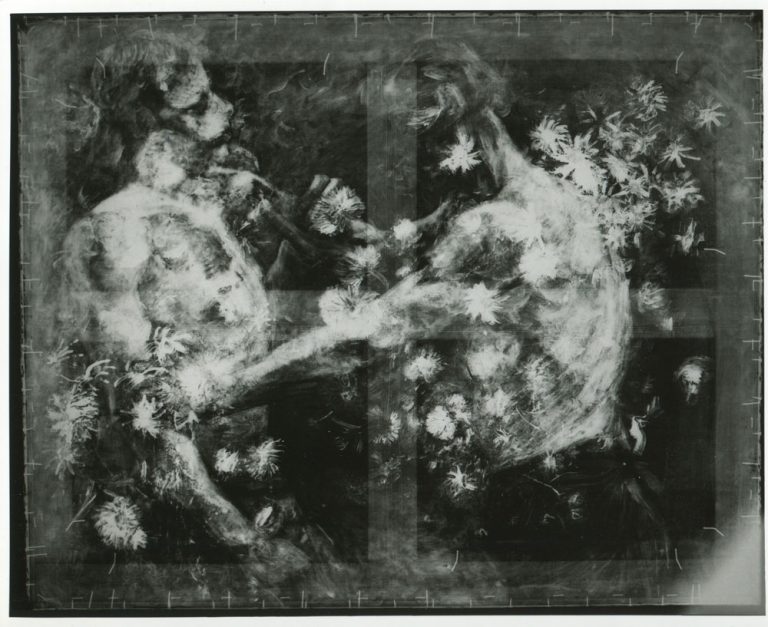

The image that interests me is neither the one painted for the Antwerp academy, nor the one painted over it in Paris. It is an image authored by the great painter, but which will never appear in an auction of his works. Its subject is neither the wrestlers that he painted first, nor the flowers that he painted second. It contains both of these, and more.

The new, composite image was created by three different scans of the canvas, from both the front and the back, using both X-ray technology and the newer, crisper ‘MA-XRF’ (Macro X-ray Fluorescence Scanning). In these scans, the sumptuous colours of the original(s) are radically reduced to itchy monochrome. Two men console one another in flowery combat. They grip their taut, vulnerable bodies in attack and restraint. Their flesh is withered. Everything is alive and ghoulish: the wooden frame – both above and below the figures – is weirdly animated; the left wrestler’s pert black nipple stares back with greater intensity than the space where his eyeball should be. Petals sprout from white human sinews. White flowers explode like fireworks around them, like they are seeing stars. Aggression and competition are indistinguishable from the simple generosity of a summer meadow.

The Third Image © Kröller-Müller Museum

This third image, constructed through the most unromantic of artistic processes – a pan-European collaboration between large research institutions –seems to me to be a masterpiece.

Connection One

In the Netflix comedy show Nanette, Hannah Gadsby tells a story about a man who cornered her after a performance and gave her some helpful advice. He tells her that she – the comic Hannah Gadsby – should stop taking medication if she wants to be a true artist. Artists must suffer, the man tells her. To make his point, he refers to Vincent Van Gogh. We wouldn’t have ‘Sunflowers’, would we, if Van Gogh had been on antidepressants?

Gadsby unpicks the man’s argument. She tells the man that Van Gogh was indeed on medication. (The drug was digitalis, extracted from a flower, the foxglove.) In fact his particular medication was likely to have had a side effect known as xanthopsia: a predominance of yellow in vision. The medication may have helped make Van Gogh’s sunflowers perversely, groundbreakingly sunny.

Gadsby says that Nanette will be her last comedy show. Gadsby explains that, as an openly lesbian woman growing up in a largely homophobic Tasmania, she learned to be funny as an act of self-preservation. A punchline, she says, is a relief from the tension created, intentionally, by the joke. In the face of homophobic aggression, she told jokes as a deflection technique, to make others feel more comfortable. But telling jokes, she says in Nanette, is a form of self-deprecation that she is no longer willing to entertain. She does not feel able to relieve the tension, because it is not her tension, it is the tension of a structurally intolerant society.

At the end of the show, Gadsby reveals that jokes she has told during the performance have been designed to conceal and smooth over the truth of the anecdotes they stem from, a truth which is not funny at all. The truth is that she has suffered shocking homophobic violence. This is trauma that has been concealed – as flowers conceal wrestlers – by punchlines. She then tells these hidden stories straight.

In her final line, Gadsby returns to van Gogh. She says, ‘Do you know why we have “Sunflowers”? It’s not because Vincent van Gogh suffered. It’s because Vincent van Gogh had a brother who loved him. Through all the pain, he had a tether, a connection to the world, and that is the focus of the story we need. Connection.’

Connection Two

Van Gogh painted ‘Still life with Meadow Flowers and Roses’ before the zinc white of the figures underneath had dried, so there are cracks in the outer layer of paint. The toxic bodies of the wrestlers break the surface of the meadow flowers into a fractal craquelure that is a replica, in miniature, of the mazy medieval street pattern of the city to which I had recently moved when I started writing. I explored my new surroundings on foot, pushing a buggy with one hand and holding up the third image on my phone with the other.

I was moved by Gadsby’s story about where art comes from: not from isolated individuals, but from their connections to other people. In the third image, that story is made into matter. In the third image, the structures that support (and are concealed by) the paint are suddenly afforded the dignity of participation in a continuous foreground. In this image, it seems as though all matter is granted an equal and undiminished right to exist. The artist himself never got to see the stitching, the frame and the layers of toxic paint all at once in their singular glory. The image is a collaboration between Van Gogh and generations of scientists, art historians and institutions he never met: from Wilhelm Röntgen, who discovered and was killed by X-rays, to Ellen Joosten, the curator of the Kröller-Müller Museum, who admired ‘Still Life with Meadow Flowers and Roses’ but could not make a definitive attribution.

I wondered if it might be possible to write a book in the spirit of this third image, intentionally. After the birth, the bedroom is full of flowers and naked torsos. The globalised flower industry collapses geographical foreground and background: someone brings a bouquet of tulips which have arrived on a lorry from Zundert, where Van Gogh was born, and another person brings carnations which have been air-freighted from Kitale, Kenya. The baby’s eye, which has no depth perception, cannot differentiate between her father’s face and the bright petals that wave and smile from their vases. Every detail, whether close or distant, is potentially vital, a curiosity, a threat.

It felt necessary to write the joy and gentleness of flowers alongside the starling aggression and vulnerability of a man stripped naked, and it seemed imperative to let the baby’s perspective shadow my own. Like an eye stuck in what it sees, the technology that produced the third image is visible inside its surface. The white lines that scar the image have the associations of an X-ray: the air of bad news, held up by a doctor on a backlit screen (I’m afraid it’s broken. Every bone is broken). In the same way, I felt the baby’s eye lodged in my chest. I wanted to write a fiction using her grammar.

Connection Three

In the third image it looks as though the flowers grow from the wrestlers’ bodies. Their muscles are like a soil. Their skin is a habitat. In this way, the third image makes visible an invisible truth: that long before they become parents, if they do, all persons everywhere support the lives of much smaller creatures on their bodies. If this third image were a book, I thought, you would open that book and the grubs that lived in the trees that were pulped to form the pages – these grubs would crawl out onto the desk, alive, in front of you.

Towards the end of the novel that came out of those thoughts, floodwater drenches the narrator-father’s notebooks. Life on paper, I wrote, was nourished by fertilizer, washed into the river from fields upstream. For the father, this is a bad kind of thriving. But it is also a new way to discover his privilege. The catastrophe makes way not for destitution but for the collation, from the debris, of a new book, with the title Fatherhood.

[1] Flower Still Lives, Kröller-Müller Museum, 2012

Caleb Klaces is the author of Fatherhood, available now from Prototype Press.