I visited Uganda a few years back, accompanying my husband, who was himself there to assist a friend in shooting a short film for an American-Ugandan NGO working in the rural north-west. The NGO dealt with water. Here was the deal: if the community applying for help could guarantee one hundred per cent latrine coverage – a toilet for every house – the NGO would guide them in the construction of a shallow hand-pumped well, giving clean water 24/7.

So, the village gave its labour, the NGO’s Ugandan team provided the knowledge and materials and expertise, and those distant foreign donors – by all accounts liberal Manhattan socialites – injected the funds to carry it through. It was a variation of the old ‘give a man a fish / teach a man to fish’ proverb, seized upon so well by Oxfam in their post-Ethiopian famine/Live Aid years, when they moved away from ‘feed the hungry’ to adopt a more ‘progressive’ approach to aid.

The Ugandan team had a secret weapon (I want to call him a trump card, but oh, how that word is devalued). Let’s call him Wilbert. It’s not an exaggeration to say Wilbert was a magic man, one who could feel water coursing through the earth and his veins, who seemed to know, through a combination of experience and uncanny intuition, exactly where to dig. He had the charismatic aura of a saint, albeit a reluctant one. He was a sorcerer in blue overalls, built like a wrestler, his muscle concealed under gleaming fleshy flesh, a bald dome of a head, a chesty laugh, and sly humour that was prone to bouts of mysterious withdrawal. Overseeing each construction, he discerned the spot for water, managed the dig, assembled the pump at the end of it like a soldier with a rifle, eyes almost closed, hands with a life of their own.

Everyone loved Wilbert, maybe feared him a little too.

He was one of them and not one of them.

He drank with the foreigners and spilled his secrets partially.

He was always a little apart.

He wanted to leave Uganda for the West (and we warned him to be careful what he wished for, as we wished him all the best).

These were idle, pregnant days for me; I was about to watch my first novel enter the world. I had some money in my pocket, and nothing to do but wait and see. Uganda was part of my more-or-less undefined understanding of Africa. It appealed to my curiosity in the way a place you’d never otherwise think to visit could.

We flew from Mumbai to Kampala via Addis Ababa on Ethiopian Air, stayed a night at a very Indian hotel on Lake Victoria, which is to say curiously unfinished and over-furnished at once: it had big rattling rooms of white tile, with gold-plastic ornate ceiling fans and mosquito-blotted walls, and the obligatory stairway to a dusty roof that revealed exposed iron rods, sentinels awaiting the construction of a next floor.

That day, with clockwork precision, a sense of dysphoria washed over me. A dislocation. The acute regret that I ever left home. I was that eager girl playing basketball in school. Throw me the ball, throw me the ball, throw me the ball. And when it came, having no idea what to do with it, and no real love of the game, I threw it away immediately. I loved to travel, but whenever I landed up somewhere, I was uneasy. It wasn’t anything to do with homesickness. I didn’t pine for my rice and dal, or miss my bed, or my family and friends. It was more like a feeling of revulsion. Even self-loathing. What am I doing here? I remember going to the Himalayas in June 2009. We were looking for somewhere to live other than Delhi, it was a toss-up between Goa and the mountains. I was so happy to get away. Happy to be in the mountains. But when I closed the door on the little hotel room in McCleod Ganj that we’d chosen as our base, I was disgusted and close to tears. Everything was wrong. The bed was dirty, the view depressing, the hotel staff intrusive, the town rundown. Travel was supposed to free your mind and your soul, but all it did, as soon as the movement stopped, was remind me how empty everything was, how futile. I remember it was 25th of June because it was the day Michael Jackson died.

Why leave home?

Why do anything?

What do I expect to learn?

That day in Uganda the sense was stronger than it had ever been.

What am I doing here?

I was not helping with the film, I’d simply come to see. Come to see Africa. What did I expect to find? It was not something I was conditioned to do. My family, over the years, had always gone out into the world with a purpose, to the UK or the US or Hong Kong or Australia or wherever, to study or to work. What they hadn’t done, not until they’d made enough money to buy foolproof luxury, was go out on a limb to experience other cultures just for the sake of it.

The next morning we stocked up on water and food and drove north. Uganda was a land of red and green, its soil, like Goa’s, was rich in iron and aluminium, a consequence of heavy rain and intense heat and time, the iron giving the earth its distinctive rust-red hue, above which fields, forests and palms exploded in the most vivid green. Palimpsestic memory, the uncanny sensation of sameness. All day, driving on the immaculate, undulating highways, white clouds above our heads. The landscape was like India’s in the monsoon, the Konkan Coast and the Deccan Plateau. The little differences defined the personality of the terrain. Yellow jerrycans, for example. Or Ford Ranger pickup tucks.

Eventually, we reached a crossroads where unidentified meats were being grilled on small barbecues and sold on skewers, several of which we sent to our confident Indian stomachs. From here we took a smaller, scrappier road, dust floating in our wake. Kids played football on patches of dirt ground. A pine plantation loomed and was gone. A white daubed sign on a house said: this land is not 4 sale, perversely attended by a number inviting enquiry to the contrary.

We were staying in a town called Masindi. Our lodge, opposite a courthouse, had a central lawn and tiny circular rooms around the edges that felt like giant toadstools in the flowering gardens. The market outside felt familiar, it contained the usual things – kitchenware and clothing stalls, mobile phone shops, hair and nail parlours, concrete-room cafes with plastic tables and crates of empty soda bottles outside. It reminded me suddenly not of India but of Ridley Road Market in Dalston, where I’d once had my threading done by an exile from Punjab who relished her freedom but could not find a suitable man.

Women wore long floral dresses or skinny jeans and tight low-cut tops showing their cleavages – a delight to see. Men wore trousers and shirts that were often just as colourful. There was lively conversation, some casual flirting, committed with smiles. My ass was the object of an appreciation I found curiously inoffensive, considering the virulent reaction I have toward the ‘Roadside Romeos’ of India engaging in what is commonly termed ‘eve-teasing’. The euphemism tells you all you need to know about the mentality of harassment and its unaccountability, women reduced to a mythical (Fallen and Other) Eve – all groping, foul language and worse, is reduced to a gentle ‘tease’. Here it felt like an exchange grounded in the common awareness and acceptance of an implicit sexuality; our bodies were not shameful things to be simultaneously feared and desired, we were not operating in the theatre of repression and asymmetry, though no doubt violence did exist. The women, on that day, in that marketplace at least, gave as good as was given.

*

The next morning they – filmmaker, husband, Ugandan team, American NGO boss – began shooting. This went on pre-dawn to post-dusk for eight days without break. They lived and breathed the film, developed a shorthand language, an economy of movement, a private set of jokes. Sometimes I went into the field with them, but more often, so as to not get in the way, I remained at the lodge, eating avocado vinaigrette and reading novels. I’d left my Donna Tartt on the plane by mistake, but there was a small, well-stocked library, which I was pleasantly surprised to see. I spent my time in Masindi reading the short stories of Doris Lessing.

When they returned each evening, after transferring the footage from the memory cards, backing up the hard drives, recharging batteries and cleaning equipment, we would all sit at a table on the lawn drinking bottles of Bell and Nile Special beer. Working all day in the fierce equatorial sun inspired a great thirst and the capacity to indulge it. Bottle after bottle went down. Sometimes Wilbert joined us. The energy they had expended seemed to make them impervious to the beer’s effects; they drank and discussed the day, going over what went wrong, debating how to approach the film ideologically, running through the shots that were still needed, what was missing, where they could go tomorrow, who they should get permission from. One of the filmmaker’s concerns was balancing the tactics that would stimulate wealthy white donors with his own radical brown leftist politics. Sometimes it manifested in a wilful refusal to submit to the ‘money shot’: there would be no smiling black children finally tasting clean water, no ragged men and women looking to be saved. Above all, he stressed dignity – there would be no material or spiritual separation before or after the well was built.

We diverged into other topics: the inherent racial bias of Kodak film, or the bizarre sudden appearance of a large group of Gujaratis at the lodge (performing that tedious Indian sin of treating hotel staff like personal servants and ordering rotis one at a time before complaining that their food has gone cold while they were waiting). And we returned on and off to the White Saviour Industrial Complex, something sporadically embodied in the earnest toothy grins of all-white NGO groups passing through, each member seemingly ready, in the words of Teju Cole, to ‘become a god-like savior or, at the very least, have his or her emotional needs satisfied’, which was also something we worried might apply to ourselves.

One more thing came up: the peculiarity of being Indian in Uganda.

*

Months earlier, when the job had been confirmed, we were given a set of warnings and precautions from the office in New York. We should prepare ourselves: we were going to Uganda. The flight, on Ethiopian Air, might be a little sketchy. The airline was basic, they were notorious for losing luggage, and we were transiting through Addis Ababa, a chaotic airport. Also, the Ugandan airport, outside Kampala, was ‘like a tin shack’. The taxi drivers could be intimidating. Uganda itself would be a shock to the system. Not to mention the malaria. My journalism professor at Delhi University went to Africa, came back with malaria, and soon died. I only had two lectures with him.

I took this all very seriously.

First we got our injections out the way (and in doing so discovered that Malarone, the high-end malaria medicine the Americans recommended, was not licensed for sale in India but, in a delicious twist, was manufactured on an industrial estate fifteen kilometres from our apartment; it became more amusing when the owner of an old Portuguese-era farmácia offered to try and build a home-made alternative from the base components – he failed), then we began to prep ourselves mentally. As the departure date drew closer, we became nervous. The filmmaker was concerned for his expensive equipment, but there were existential fears too. The first rung: disease, death, accident. The second: discomfort, alienation, food poisoning, the failure of cultural adjustment, miscommunication, a bad working environment. We were, after all, going to Africa. None of us had been to Africa. My visions of Africa were amorphous, but always lined with an unfocused amoebic fear.

As it turned out, the flight was wonderful, full of bonhomie and freshly brewed Ethiopian coffee brought round in battered vessels that somehow renewed a faith in life. Then there was Addis Ababa airport, a shabby, lively revelation, scuffed and a little odd, unique but reassuring, and somehow inclusive. There was a cafe right in the middle staffed by beautiful, no-nonsense, kick-ass women – and more coffee! When someone inside wanted to smoke, they were directed to the small table just out the door – still firmly within the terminal. Life flowed charmingly, free of the homogenized sterility of the ‘global world’, and also free of Indian morality (though not free of men on guard with machine guns).

When we finally arrived in Uganda, all tension had gone. The ‘tin shack’ was revealed to be a perfectly neat little airport, and the taxi drivers barely tickled in their persistence. Outside, we were amazed to see how clean it was. So much cleaner than India. So much easier than India. We laughed at the joy of discovering a new land, but also at our foolishness for having taken those American warnings so completely to heart. We’re Indian, we said. We’re from India.

Not once before that, for whatever reason, did we stop to consider that we came from India.

Coming from India, one is reminded that nothing is that hard.

Nothing is so shocking. Nothing disturbs.

By the end of it, I began to think I had travelled to Uganda sideways.

I have always felt an affinity for the foreign correspondent Ryszard Kapuściński. I thought he travelled to Africa more or less sideways too. Coming from Communist Poland, without the budget or arrogance of his Western contemporaries, he was content to live among those he wrote about, to eat their bad food and suffer their diseases, which were not so alien to him.

His writing, even in translation, was beautiful, incisive, surprising, delightful, exciting and finely crafted. I remember the first flush of reading, devouring several books in a couple of weeks. Here was a writer who elevated reportage to the level of great literature. Others agreed. Opening the cover of The Shadow of the Sun, one is greeted by acclaim:

‘Kapuściński alternates between plain prose and shimmering imagery, using understanding to dispel easy stereotypes about Africa and Africans’ – Outside

‘[The Shadow of the Sun] bears the distinctive mark of all [Kapuściński’s] work – raising reportage to the level of grand history and philosophy’ – Time Out New York

‘With acute descriptions and broad commentary, [Kapuściński] uncovers the beauty [of Africa] without shying away from the brutality of life’ – Conde Nast Traveler

How strange then, how disappointing, to learn that a great deal of Kapuściński’s work was fiction, was fact muddied by fudge and fabrication, the approximation of the actual, the spirit of the matter – a novelist’s crutch – rather than the letter of the law (and what you notice, of course, in all that praise, is the absence of African voices).

Where Kapuściński claimed the fish in Lake Victoria were so big because they fed off Idi Amin’s victims – ‘a wonderful metaphor’, his biographer Artur Domoslawski said. The truth was far more mundane: Nile perch were introduced to the lake in 1950 to boost the fishing industry, and the invading species subsequently almost decimated the smaller native cichlid, growing fat in the process.

Tall claims appear all over his work.

He never met Che Guevara, let alone befriended him.

Below the line in a Guardian review of Domoslawski’s exposé, Ryszard Kapuściński: A Life, one commentator named Goremsa, said of The Emperor, Kapuściński’s account of the last days of Haile Selassie:

Presented as journalism, it was of course fraudulent, as anyone familiar with Ethiopia in the twilight of its empire immediately knew. We all said so at the time, but people were so infatuated with the ‘brilliance’ of the writing that nobody (least of all the admiring critics) would listen.

He/she (it feels like a ‘he’) goes on to say:

Outsiders’ views of Africa and Africans are (alas) largely shaped by other outsiders . . .

A little further down, Mojo444 says:

. . . as an Ethiopian who lived through both the Haile Selassie and Derg periods, I was quite embarrassed by this book. I immediately sensed that the book was a journalistic caricature of a country, people and leadership.

Leafing through his books again, it seems quite obvious as to why I’d felt, on first encounter, the thrill of a great fiction writer. Now I was disheartened and also chastened. I resolved to be more vigilant, not least with myself. Why did I assume he would tell more of a truth? Why had I assumed, because the books were about places like Africa, which in my head had a kinship with India, I’d have been able to detect their veracity or lack of it?

Had I accepted the truth of his depictions because they were beautiful and he was not British or American, or was it simply because I was ignorant of African voices? I thought back to watching Slumdog Millionaire in a cinema in Mumbai and being desperately embarrassed by Dev Patel’s accent, along with his character’s words, which were equally out of place. I thought: how could anyone believe this? But an audience in New York and London didn’t know and didn’t care. As I didn’t know or care until I read that the Latin American accents in the TV show Narcos were all over the place.

Nicholas Shakespeare, Bruce Chatwin’s biographer, in a review of Domoslowski’s book in the Telegraph, wrote:

Kapuściński laughed when García Márquez asked him: ‘You tell lies sometimes too, don’t you?’ In Africa, his stories grew in the heat. Grass that sprouted less than a metre high leapt to three metres.

Surely, coming out of India, I should have been alert to these signs?

I thought now about the ease and comfort with which I travelled ‘sideways’ from India to Uganda, a highly educated middle-class woman, facilitated by an American NGO. I recalled the speech by one of the local Ugandan women who worked for the NGO, an angry, controlled, intelligent monologue, regarding the ways in which women in Uganda were not free.

Just because you see something, doesn’t mean it’s there.

Later I got to thinking about Chatwin, and his Patagonian dinosaur skins, and I thought of the rare fungus that attacked his bone marrow, or the rotten thousand-year-old egg that made him sick, both lies told with a wink to distract from the AIDS that would kill him. Were Kapuściński’s lies Chatwin’s too, a personal pathology? Or were Kapuściński’s somehow a consequence of growing up in a totalitarian regime – the colonialism he wrote about becoming a mirror for Soviet oppression, the Ethiopian court psychosis a mirror of Polish bureaucratic dysfunction – whereby one had to be both evasive and obedient to the system to survive? Did this become a mitigating factor at all?

I found I was more disappointed in Kapuściński.

I realized I was much happier to grant Chatwin a free pass, a nod and a wink. The histories of his world didn’t rise or fall on anything stable. Reading him, it was always clear to me he was honest about his evasions, or at least uncaring. His was a realm of magick, and Chatwin, in the words of anthropologist Edward Burnett Tylor, was, like all sorcerers, ‘at once dupe and cheat, [combining] the energy of a believer with the cunning of a hypocrite.’

It was Kapuściński’s lies that seemed egregious, wearing the mask of reportage and circling the carrion of great history. How could I read him now? Gingerly, I supposed.

I wondered if I could at least ethically convert him to fiction; take him into that private sphere where close friends make jokes in bad taste that would otherwise call forth a Twitterstorm. But surely to do so would betray an ongoing ignorance of African voices and lives?

*

Two years after Uganda, I travelled to the US for the first time in twenty-four years. Unlike our Africa trip, there were no butterflies, no trepidation. Despite the militarized police force, the various mass shootings, the blatant systemic racism (which, to an outside observer, made it open season on African Americans), the crippling inequality, the mass surveillance and the generally excessive and aggressive number of rules, America had a free pass. A skin of exceptionalism.

But we landed in San Francisco to a tatty airport – so many notches lower than Addis Ababa’s on account of its po-faced sterility, and quite depressing after flying out of Hong Kong’s. We encountered a surly, demoralized workforce and a brutally suspicious set of immigration officers. I couldn’t recall a more threatening politeness.

‘Step away from the counter, sir.’

[He steps away.]

‘Purpose of visit, madam?’

‘Family.’

My cousin picked us up and we drove to another, elder cousin’s house in San Ramon. Images from classic American movies played before me: the freeway, the mall, hundreds of red tail lights slowing in traffic, row after row of suburban houses with pools in the back on curving asphalt, sprinkler systems, the desert beyond, a golf course.

E.T.

Pump Up the Volume.

Growing up in India, my cousin and I had Luke Perry posters on our walls.

When we arrived I was amazed at how big everything was, how much stuff everyone had. That’s no great observation. We drank some wine, ate sandwiches labouriously constructed from layers of material inside plastic containers inside a vast fridge.

The next day, walking around the suburbs, getting lost in the depopulated never-ending sameness, the dysphoria, compounded by jet lag (we had gone back in time), would not leave. And on the train into San Francisco a day later, I had a vague unease, a sensation of threat.

It was the silence, more than anything. Everyone busy looking at their phones, or else staring into oblivion. Two men swaggered on with their music blaring and dominated the space, talking loud enough for everyone to hear, performing to the carriage. They were only really talking with as much energy as people in Uganda or India.

But the surrounding silence amplifies. And you collaborate with your environment. Though perfectly attuned to noise and chaos at home, you fall silent too. And, once silent, you feel the threat.

Dismounting at Powell St. Station we stepped into a scene of almost tragicomic homelessness – homelessness and depredation and neglect everywhere, at one point almost stepping over a passed out, stinking body bisecting the sidewalk.

Why was this more shocking than India?

In India, the big cities specifically, the homeless are both everywhere and nowhere, vanishing in plain sight by their numbers, while also operating as functioning members of society. There is such a permanent level of poverty that it no longer has the capacity to shock (unless you’re a foreigner just arriving). And in India, it is virtually impossible to use the formulation ‘they have fallen through the cracks of society’, since poverty and inequality is society, and society is constructed on the tacit acceptance (mine included) of the labour and exploitation of the poor.

But America was not supposed to be this way.

A few weeks later in New York, we stayed in the apartment of the director of the NGO we had worked with in Uganda. Her apartment was in a block in Brooklyn on the eastern edge of Prospect Park, on the edge, too, of gentrification. Just north, one could feel the unstoppable tide of yoga studios, cocktail bars and bespoke dining experiences approaching. But the block itself, and the immediate neighbourhood, was still demonstrably poor, a decrepit urban space of Checkers and Wendys and the Gospel Truth Church of God. Though I was glad not to be living in a hipster bubble, I’d be lying if I didn’t admit to feeling a little uneasy in these streets, especially coming home from the subway late at night. A day or two wandering around dispelled that fear. Looking up and saying hello and good morning and holding doors open and making conversation did the world of good.

What continued to inhabit me was a feeling of silence and emptiness, similar in fact to that which I felt wandering the moneyed neighbourhoods of San Ramon. The sense of a great separation between the essential decency of people and the brutality of the systems in place. It manifested in different ways: in the police van pulling up alongside and aggressively questioning a young black male minding his own business on the sidewalk near the Brooklyn Museum in broad daylight. Or, in the ubiquitous presence of the ‘nutritional facts’ calorie labels pasted on every wrapper (and realizing how much corn fructose and junk was inside everything).

Around me, I felt America crumbling and holding on, much like everywhere else in the world. And yet the facade was in place. I thought of John Carpenter’s Reagan-era yuppie-capitalist satire sci-fi, They Live. Put the special glasses on, disrupt the signal, and one might begin to see the third world living within the skin of the first. One might see how it could, to hijack the words of writer and artist Dale Beran, exemplify ‘a cascade of empty promises and advertisements – that is to say, fantasy worlds, expectations that will never be realized “IRL”, but perhaps consumed briefly in small snatches of commodified pleasure’.

Weeks passed in NYC, money bled, I took commodified pleasures where they came and my dysphoria grew where it elsewhere dissipated. I walked the High Line and felt nothing at the end of it. I had come to an alien place, somewhere far away from the world I knew. The doormen outside Tiffany’s. The never-ending stream of restaurants and apps. Jessica Jones on Netflix. Everyone in the know. Going somewhere all the time. Constant movement and gratification and reservations. The brutally unforgiving wheel. Spicy Korean Chicken Wings at Boka. Ben Rojo’s cocktails at Angel’s Share.

Persisting: the myth of the American as a fully realized being. The default setting, the empire that we’ve all been sold, the one whose image has been imprinted on the global retina. This myth persisted despite so much evidence to the contrary. Like the light of a long-dead star, The American Dream was still so strong.

*

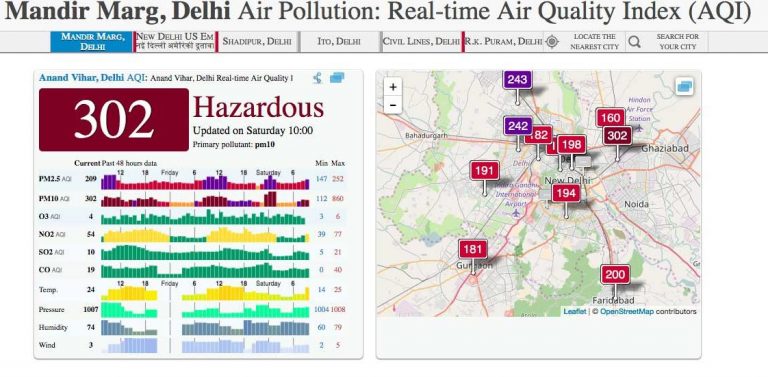

Last September I travelled from Delhi to Berlin to speak at a literary festival. Delhi, my family home, now one of the most polluted places on earth, was going through a bad spell (though nothing like its worst), the air so full of toxic particles you could almost pluck them out and eat them, a cartoon image of poisoned candyfloss clouds. The stink of sulphur was unmistakable and even a short stroll outside led to breathing difficulties. Doctors’ prescriptions for children, elderly and at-risk individuals amounted to one word: leave.

But the air isn’t Delhi’s only problem (sometimes, in fact, it merely feels like the physical manifestation of its deeper malaise, to those privileged enough to think that way, at least). Though the city is incredibly stimulating, and at times utterly bewitching, it is an exceedingly aggressive, desperately unequal place, a store of vast wealth and residual callousness (my own included) trickling down the layers to its citizenry. I remember a friend from California, an Indian-American, who had ‘returned to the motherland’. On his first week we went to one of the malls in South Delhi, and he stood holding the door for a group of people as we entered – a mark of basic manners. No one thanked him, and the stream kept coming, no one thinking to stop and let him through. He was a sap, he had showed his weakness and it was being exploited.

Well, that’s Delhi for you.

Don’t expect anyone to be kind.

You make your own luck.

Even leaving the city can be tough. Weakness is preyed upon at the airport check-in counter. People routinely jump to the front of the queue, with a swaggering disregard for those stupid enough to get in line. Officials, the only ones who can conceivably regulate it, just let it go, they’ve long since given up. Delhi, and India, is a place where authority so brazenly does not care for any of its rules.

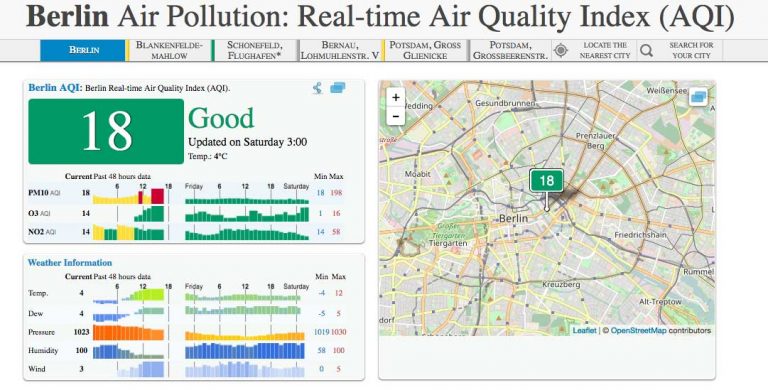

What a difference, then, landing in Berlin. In Berlin, the struggle stopped. Our hotel was beside the Tiergarten, the air was sweet and calm, the streets clean, people were at ease, no one was out to cheat you. Crucially, the collective gaze was neutral. People saw one another, but without penetration, seemingly without violence. In Delhi, more than anywhere I know, the gaze is penetrative and violent, and so is the opposite of the gaze, the privileged presence. I may not stare, I may not wish to be stared at, I may actively despise the hard stares of men (and some women), the mixture of contempt and anger and lust and hatred and incomprehension they project; but I must also acknowledge how the causes of those stares are not independent of the life I lead. They are not independent of the opportunities I have had, the linguistic superiority I am afforded, the access I possess, which I see as a right but which others may consider an unfathomable luxury.

In short, the violence of my existence is a sum within the violence of their stares.

Ah, the trauma of Delhi and its class divisions.

At some U-Bahn stations in Berlin, there were no barriers. You policed your own payment. Outrageous!

Walking the Berlin streets for hours and hours, seeing everyone in their shorts and shirts and summery dresses – it was an unseasonably hot week – laughing, joking, holding hands, drinking beer, lazing in the Tiergarten beside the canal, I had a vision of how things could be, and in the soft twilight, sitting in the park drinking cans of beer with my husband and a childhood friend from India, I felt a frictionless melancholia take hold of me. Wandering the streets like this is something almost no one in Delhi would voluntarily do, not only because of the pollution – the city is uniquely constructed to thwart walkers who wish to escape their own colony gates. But the more time I spent in Berlin, seeing people, young and old, amusing themselves with a kind of genderless fun, something else rose up. I discovered I scorned them – you don’t know what it’s really like out there in the real world.

It was the painful recognition that I already missed Delhi. For all Berlin’s culture and liveability, I was growing bored by the absence of drama, the way society ran on rails. This didn’t bode well: feeling an addiction to a place you claim to despise, and a loathing for the place you aspire to be.

The air pollution levels at the time of writing, 18th Feb 2017. In early November 2016, the reading on the Air Quality Index scale at the US Embassy in New Delhi went off the chart at 999. This score relates to PM10 or particulate matter between 2.5z and 10 microns wide, essentially dust. For reference, a human hair is 50-70 microns in diameter.

I was reminded why so many people travel to India for the ‘trip of a lifetime’, returning broken or illuminated or intoxicated or enlightened, and, despite the perceived hardships they may have faced, almost immediately yearn to go back. In India, all life seems present and possible, usually all at once. It’s why books like Eat Pray Love appeared. It’s why the yoga pilgrimages happen. Return to the source: India as the specific balm for a specific lack in the soul of the West. Latin America must have its own set of devotees, too, just as Africa does. Anywhere on the fringes, away from that global middle that has invaded our cinema halls and fridges. In return, we give wisdom to those wishing to learn: the shaman who was once the object of derision is now the purveyor of recalibrated dreams.

I thought about all this, as I read the newspapers and watched the news on TV in my hotel room. We were at the tail end of the news event named ‘the European Migrant Crisis’. Germany, ironically, had done so much to help. I suddenly thought of Wilbert from Uganda, driving a taxi in New York, selling me a goat’s leg in Ridley Road Market. Or what else? Kneeling in church? Working as a plumber – that would be a good one. Sitting opposite me on the U-Bahn. Or maybe drifting on an overcrowded boat in the Mediterranean, shorn of his sorcery, which was no good to him here.

And then I went and checked Facebook, and saw Wilbert was still in Uganda, only he’d left his old job and moved to the capital city to work for another company. There he was, wishing people happy birthday, sharing funny videos, going out for beers. Chastened again, I supposed I was the same as everyone else.

Photographs © Matthew Parker