I was born in 1969, in a red-brick hospital just outside Bradford which has since been converted into a psychiatric unit. The very first words that I heard were uttered by my father. They were the Shahadah – the Islamic declaration of faith, whispered three times into my right ear. A couple of days later, my mother took me home to a tiny, overcrowded terraced house. I was her third child, born with Pakistani values and a Muslim soul.

I knew I was Pakistani long before I knew I was English, just as I knew I was Muslim long before I knew I was British. It’s hardly surprising. There was the blatant declaration my mother, Umejee, made me repeat from the age of about four:

‘We are Pakistani.

Pakistani children are good children.’

And there was the way that she and Dad always referred to Pakistan and never England as home, so that I knew more about the imprisonment and execution of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto than I did about the Winter of Discontent; the way we only spoke Punjabi in the house; the way our food smelt and tasted so different to English people’s and how we used our hands, not knives and forks, to eat.

On the odd occasion, my parents would surprise me with signs of assimilation. My mother was such a staunch supporter of the monarchy that she regularly made me write letters to Her Majesty, asking if she could go and work for her at Buckingham Palace. ‘I am a very clean lady,’ I wrote, as Mum dictated. ‘My own house in Bradford is very clean. You are very decent people. You are like my family. I will do what you need, cook, clean, iron.’

Umejee, like so many other Pakistani women, held the royal family in great esteem. To her, this institution, headed by a matriarch and based on duty, respect, loyalty and honour, epitomised everything a family should be. ‘You are like a Pakistani family. I will work for you for free’. We never heard back from Her Majesty.

Such pro-integration incidents were rare, however. For most of the time, I couldn’t forget what I was, who I was. I had ‘the Aunties’, a group of interfering women, busybodies all about Umejee’s age, to remind me. The Aunties had mastered the art of disapproving of non-Pakistani habits. They would talk of Pakistani concepts: what rishta, marriage proposal, they were looking for for a teenage son; what izzat, honour, was lacking in the British-born generation; and what perishani, sorrow, there was for them as parents of this British-born generation. It was very subtle – sometimes it was just a look, and sometimes just a sentence: ‘I see that your daughter is wearing trousers and not shalwar kameez at home, Begum,’ The fear of chastisement on a city-wide scale was enough to keep most people – including me – in check.

By the mid-1970s, it was obvious that we, the Pakistanis, were not here just on a temporary basis to work in the mills and on the buses of Ingerlernd (as Umejee called her new home) but that we were now Here To Stay. And that Here To Stay didn’t necessarily mean Here To Integrate. For the 30,000 or so of us in the city, there was a process of ‘settlement by tiptoe’ – we took on some aspects of British life by working in its factories and sending our kids to its schools, but preserved Pakistani life through language, religion and culture. We set up our own mosques and madrassas, ran our own businesses – goldsmiths’, curry houses, fabric shops. We set up our own entertainment in the form of Asian record shops and cinemas.

Bradford, the city that was once called Worstedopolis, on account of its production of fine worsted wool, the best in the world, was now Bradistan. A home from home for the Pakistanis.

Of course this segregation had consequences. We were subjected to racist taunts on a regular basis – and not just from members of the National Front and the like-minded Yorkshire Campaign against Immigration, who held regular rallies in the city and shouted for us all to be sent back to our real home, ‘Paki-land’. The dreaded P-word would be hurled at us at any place, at any time, like the day Umejee and I went on an outing to Bridlington with a group of about forty Aunties. As we shuffled on to the beach dressed in brightly coloured sparkling shalwar kameez, looking more like wedding guests than daytrippers, clutching our stinking lamb kebabs, samosas and chicken tikka and chattering away in Punjabi, we were greeted with a torrent of ‘Fuck off, you Pakis!’ and ‘Get out of here, you wogs!’ by a group of pasty white bathers.

‘Fuck off, you white shit!’ I shouted back. I always had to respond to abuse with abuse. I didn’t care. I certainly didn’t want to be like my Dad, who treated all white people with the utmost respect and deference. ‘Mr Councillor Sir’, ‘Mr Police Officer Sir’, ‘Mr Plumber Sir.’ Or to be like Umejee – who had adopted a strategy of ‘smile and ignore’ for years, so that even when she knew that market traders were being racist by ignoring her or throwing her change at her, she just grinned at them and called them ‘Dahling’ or ‘Love’. ‘Dahling, how much these grape?’ ‘Yes, love. I need apple, please.’ I had no friends at school because, quite frankly, the girls there all thought that I was weird, what with my failed attempts to explain to them why I had two Christmases a year called Eid, the dates of which were set by the sighting of a full moon in Saudi Arabia, my lack of participation in extra-curricular activities such as nightclubbing and boyfriends, and the addition of flared trousers to my school uniform.

By the time I’d hit my late teens, I’d had enough of this conflict, of trying to please everyone, of trying to find some workable balance between my home life – imported Lahori TV dramas, the constant odour of frying garlic and ginger, matchmaking Aunties and my school life – David Bowie albums, Vogue magazines and Madonna lookalikes.

So I left Bradistan in 1989 – the very same year that hundreds of Pakistani men gathered in the city’s centre to set light to Salman Rushdie’s ‘Satanic Verses’ and in so doing, emphatically stated that they were not like the people of Ingerlernd – that they still had their own separate identity, culture, language, religion and customs even though they had lived here for decades. Them and us. Which one are you? You must choose.

By now, I found ‘the community’ that I had grown up in too stifling, too set in its adhat, its ‘back-home ways’, and too reluctant to integrate. Yes, I knew that I had been born with Pakistani values and a Muslim soul as everybody kept reminding me – but I was also born with British citizenship. I was British.

I still go back to Bradford to see my family. Leaving the city’s bus station on my way to Umejee’s house, I pass the solid bronze statue of JB Priestley, who once said that ‘The England admired throughout the world is the England that keeps open house,’ and ‘History has shown that the countries that have opened their doors have gained.’ And I wonder what he would think of this place now, where just under 20 per cent of the population is Pakistani.

I can still see the Pakistan I knew as a child. It’s impossible not to. In fact, Bradistan has expanded – so there are now even more neighbourhoods and schools where you’d be hard pressed to spot a white face. Still the main language you will hear among shoppers in the city centre is Punjabi; still the taxi drivers rant on about who assassinated Benazir Bhutto before they opine about Cameron and Clegg’s coalition government; still the Aunties insist on sending their offspring back to Pakistan proper to get married. Still it is the flag with the crescent and star you will see proudly displayed in shop windows, alongside bargain offers for international phonecards that allow you to keep up to date with all the latest gossip from relatives back in Lahore or Sialkot.

For years, Bradford has been seen as a city of discord, a city of racial and religious tension. Various reports have pointed to long-standing problems of ‘racial self-segregation and cultural lives’ and suggested that ‘the complete separation of communities will lead to the growth of fear and conflict.’ Too late. We’ve had segregation in this city for as long as I can remember – it was there when I was growing up and it’s still there now. In fact, it’s worse. I have no doubt that there are many Pakistani families in Bradford who do not live near, go to school with, work with or even ever speak to white people. And of course the reverse is also true.

Still Bradistan thrives.

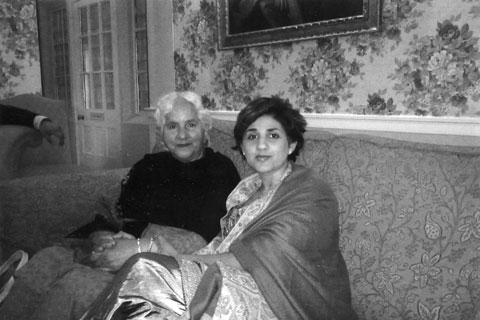

All photos are from We Are a Muslim, Please, Zaiba Malik’s memoir, which is published by William Heinemann.