1. This is How I Remember It

Mum says, ‘Don’t sleepwalk back into your bedroom tonight, there’s a strange man in there.’

– But it’s my bed.

– You’re not Goldilocks.

– I don’t want a strange man in my bed, Mum –

– Don’t want doesn’t get, child.

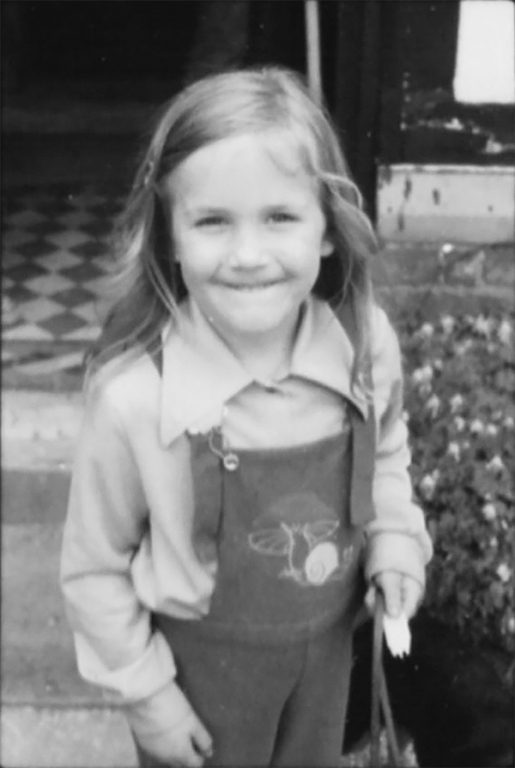

My mother isn’t good at calling me by my first name. She said she chose it because my father wanted ‘Jemima’ and the nuns in the hospital were circling, so she panicked.

I’m pinch-my-cheeks awake and watching black rats tumble on the other side of the Perspex window. It’s more of a Perspex door on the ground floor: a temporary cover meant to protect me. This is not-my-bedroom, it’s an outbuilding Mum calls ‘the pottery’ to make it sound less rat-ish. I watched her clear it out with two men from the pub, the same men who poach Wye salmon which she then poaches with cucumber and fennel. Soon there was this mattress on the slab floor and Mum had a makeshift kitchen and the loo worked in the outhouse (‘Not the bloody ‘toilet’, darling, please’).

I watch the rats, blurry through the plastic.

It’s that funny not-quite time in the countryside: long after the impatient dog-fox has barked himself out, but before the birds and the farmer are up. I don’t want to sleep.

Mum said the ad in the Times read ‘Rehearsal Space for bands, no heavy metal,’ because we lived in a big house with an alcoholic and the gourmet weekends hadn’t worked. She told me living in the outbuildings would be fun, like Swallows and Amazons, like Ratty or Badger in their dens. She said she’d bought Cleo my Great Dane a white caravan of her own to live in; she said men were coming to our house to make noise so we had to get out and it would be an adventure.

‘Like Rupert Bear goes on an adventure?’

‘Christ, I don’t know Tiff.’

She told me I’d have to keep my cats and kittens and the Great Dane and the goat, the Silkie chickens and that Bantam, in fact all of your menagerie, out of the main house.

‘What about the goldfish, Mum?’

‘They’re fine, brains of Britain, they’re in the bloody pond.’

The first band to stay at our house was Black Sabbath: the specifics of Mum’s advertisement had not worked, no heavy metal. She told me the next band were coming from London where once she had all of her good times in a flat behind Harrods (because it was the 60s and everything was better then, particularly round the back of Harrods). She said this band sounded royal and jolly, and when they arrived with a white, baby-grand piano, she had high hopes.

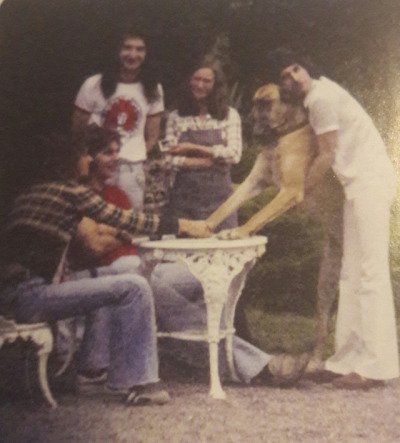

Freddie Mercury hugging Cleo the dog

The house – our house – is as blurred as the rats beyond the Perspex, but I know it’s tall and Victorian gothic. I know it’s a Vicarage because there are graves next door. I also know our living in the pottery is the house’s fault. It’s because of the hall. We have a hall so big your voice echoes up to the rafters and the drop from the gallery is so deep that the day I finally jump, I’m sure I’ll fly. It’s here where it happens: the acoustics, Mum calls them.

That is why they come.

The bands prance on the black-and-white floor tiles, up and down the carved oak staircase, all along that tall and wide gallery, like crazed Pied Pipers. They rehearse, black cables taped to the tiles and Marshall amps buzzing. The glass in our windows shakes. I like to sneak in and watch. Children are invisible here.

Mum keeps the Parish Council letters of complaint under the fruit bowl.

2. Meet me under the stairs

She’d kill me if she ever found out I was here, but if I nestle into this corner on the stairs of the big house (just before the steps swoop round past the fireplace and down onto the hard chessboard tiles) then no one will see me. My feet are freezing and I still have gravel stuck between my toes. Two cats have followed me in, Tramp and Meissen, tortoiseshell and white. They are sitting beneath me on the keys of the white piano: the white piano the band brought with them, just below the stairs in the big house.

And now I am here.

I don’t know him very well, but I like to watch him (and the tall man with the halo of black hair who is very kind and is the one who plays the guitar so loud the glass in the windows shakes). I know this other man is called Fred and I know he has a friendly girlfriend called Mary. His front teeth press out of his lips. He is sitting at the white piano now, beneath me, and in the early morning dark he is playing. I press myself into the wall: the cats scatter over cables and guitars but he doesn’t mind. The sounds he is making are slow and it makes me sad. Then it becomes bright and silly. He sings something about the seaside and Clementine.

I am sleepy but I listen.

3. This week: a call to my mother in Portugal

‘So what else do you remember, Mum?’

‘It was a long time ago, Tiff.’

‘Did you know Freddie had a cat called Tiffany?’

‘No.’

‘Do you think?’

‘I suspect it was something to do with 5th Avenue, diamonds and Audrey Hepburn, not you.’

‘Oh –’

‘I mean he wasn’t wild about children.’

‘How do you know?’

‘Well maybe it was just you.’

‘—’

‘I do remember the farmer. He said his herd was worried, he banged on the door at 5 a.m. woke us all up and told us Queen had spoiled his milk. Not that he knew they were Queen, they weren’t famous then, you know. And there was that time I nearly killed you –’

‘Why?’

‘You told your primary school friends they could come home with you and see a rock band. They all followed you down the main road, a pack of seven year olds all marching up the drive like little bloody Von Trapps. It was ghastly. I had to take every one of them back home in my beach buggy. Of course the whole village was fascinated, but luckily the post mistress was deaf.’

‘Why lucky?’

‘She was nearest.’

‘Oh.’

I think of my mother, alone now, in her house in Portugal on a small hill, surrounded by genet cats and good people. Still, she’s alone apart from –

‘How are the dogs, Mum?’

‘Oh, they’re okay. Bella is peeing everywhere. She’s getting old.’

‘And you?’

‘I’m seeing the specialist on Friday. Jay is taking me.’

‘Will you send me the recipe?’

‘Which one?’

‘The one you said Freddie liked.’

‘Well he ate like a bloody sparrow.’

‘But they asked for you, didn’t they? You went with them to the recording studio, to Rockfield, to cook for them. We left the Vicarage and you cooked Bohemian Rhapsody –’

‘Yes. I suppose.’

‘What was his favourite dish? Freddie, I mean.’

‘Beouf en croute. I made pike quenelles, the poacher boys who brought me Wye salmon would give me the pike free. But let me rest. I’m tired.’

‘I’ll call you tomorrow.’

‘I’m out tomorrow –’

‘Are you going to see the film?’

‘What film?’

‘Bohemiam Rhapsody. They filmed it at Rockfield studios, you know.’

‘Well, I’ll try. You know what I always say.’

‘Never live –’

‘Yes, never live in the past, Tiff.’

4. Pike Quenelles for Queen

Dear Tiff,

Here is the recipe. Feeling a little better today. He wants to do more tests next week. Taking Bella to the vet’s later. Having a rest now.

Pike QUENELLES for QUEEN

Pike in the 70s was not a delicacy in England as it was in France. A guy would come to my door selling salmon and salmon trout. I didn’t ask too many questions. We weren’t far from the River Wye. He gave me pike free, though, ‘Bloody muddy ugly bugger’ he called it. So, I thought, what shall I do with this ugly, muddy bugger? I suddenly thought of my last visit to France. (I’d always give a choice of two mains with this as some baulk at pike).

3 lb of Pike, or you can use Halibut

1 large onion

loads of parsley

loads of salt and pepper

4 ozs butter

6 ozs flour sifted

2 tablespoons of cream

3 egg whites (loosely whipped)

Into a casserole, put the fish, equal amounts of milk and water, loads of parsley, 2 bay leaves, and salt and pepper. Cook gently till it is falling off the bones, let it cool, and then remove all the bones and skin. You will only end up with about 2 lb in weight. Reduce the stock, and then sieve.

Now melt 2 ozs butter, add flour, keep stirring, then add stock, and some cream, more salt and pepper, plus 2 egg whites. TASTE. Let it go solid and cold, then add the fish. Add the last egg white and the rest of the melted butter.

I was lucky enough to have a liquidizer in the 70s, so use one of these to mix altogether. Put this in the fridge overnight. Then the next day, roll into small sausages, poach in any leftover fish stock or water. Takes no more than five mins. This is how I did it in the 70s with no money! It was so satisfying to make these with a free ingredient. The band loved it.

5. Joining some of it up, September 2007

My stepfather, Fritz, has died and we are sorting through his belongings. It’s what you do: grieve, sort stuff, play a trumpet to his body in the chapel in the Portuguese village in the middle of the night.

Mum finds it in a bottom drawer, the little unexpected thing, an old master tape with Fritz’s writing on the surprisingly small yellow-and-white box.

‘Smile,’ it says, as if we could.

Inside there is a piece of lined paper. Fritz’s writing says, ‘Budget, Artist: Smile, 4 Titles for Ultimate Studio Release, studio time, £650.’

‘I’d forgotten,’ Mum says. ‘Of course, Fritz produced them, Smile. The Queen band before Freddie joined. They didn’t work out at all. Poor Fritz.’

We put the old spooled tape in a box beneath the stairs.

This – at least – we forget.

Tiffany Murray is the author of Diamond Star Halo, available now from Granta Books.

Cover photograph © Anpalacios