Today, one in seven people is a migrant. This year, crossings of the Mediterranean Sea have already exceeded 300,000, and at least 2,500 lives have been lost in the process. What does it mean to be a migrant – or a refugee – in our time? What human rights can we rely on? And what hope is there for those who have fled their homes? Granta asks its authors to share their reactions to this profound human crisis. Click here to read the other responses in this collection of statements, poems, images and personal reflections from across Europe and beyond.

Because

it’s difficult to feel the edges to the words

‘refugee’

and

‘crisis’, because

these words stretch round the things’ outsides, until

we can’t see to the end of either’s fences,

we feel discomfort.

For us, discomfort is a hard feeling.

Almost as hard as hate.

Almost as hard as fear.

It is a word we can’t break out of.

DO NOT WORRY!

To stretch a word makes it uncomfortable.

Before it breaks it ladders and, within it

there are windows. Look through

each word; behind it

there are people.

‘Good’ is a word standing in our way,

the biggest: let’s forget it.

Instead we should say: grandma, socks, spaghetti.

Instead we should say: dollhouse, tablespoon, school uniform.

Let’s substitute: underpants, dusk, candy, moped.

These are small words, each one stretching

not so far. Then we will say: park bench, moustache, hairspray,

breakfast cereal, dustpan, bus queue, lipstick.

We will say: birthday, baby cream, bike, doorbell.

These are the words of revolution.

With a little help,

words becomes flexible.

They break. Each small word helps us

To do one small thing.

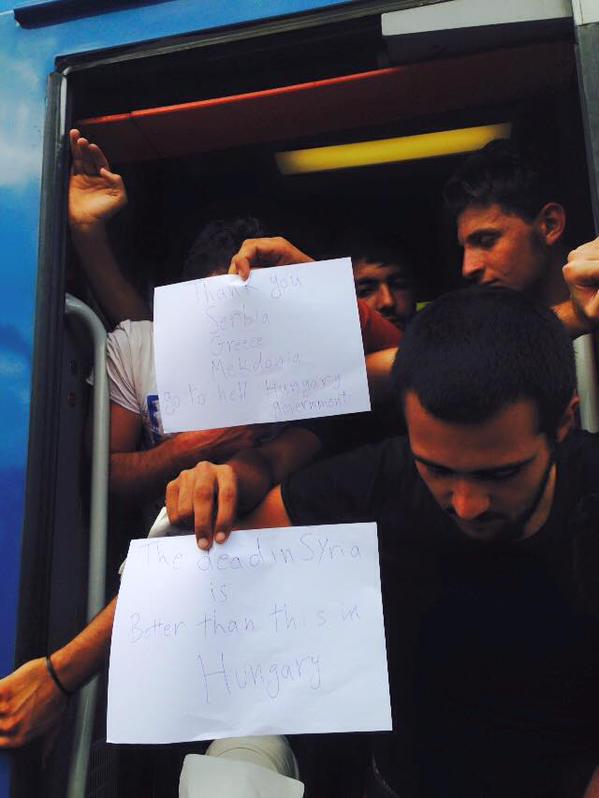

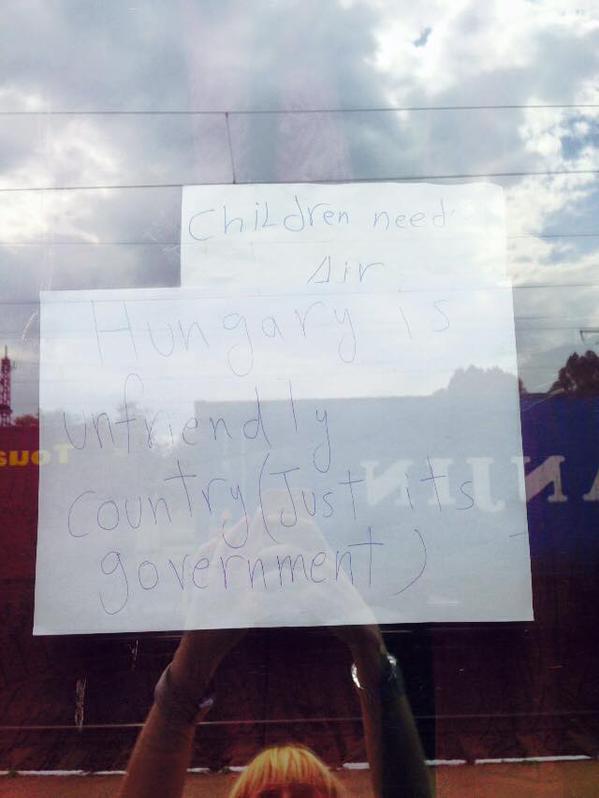

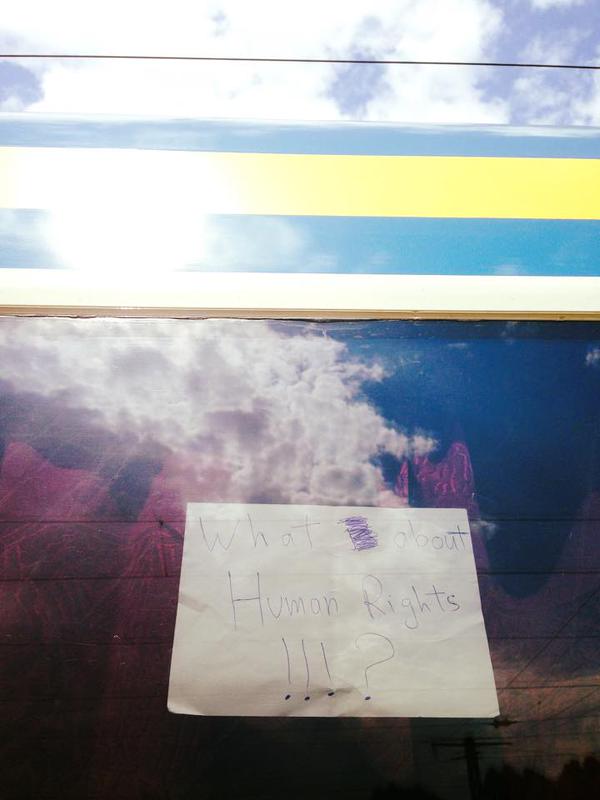

The placards I see stretch

a few words only round the situation.

A few words only.

Images courtesy of Anna Kovács and Gergő Plankó, Bicske, 2015