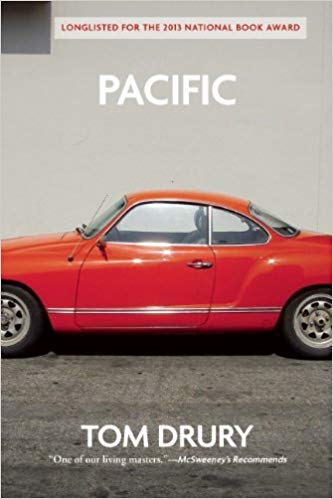

I don’t really remember what happens in the books I’ve read and loved, and often I don’t know why I exactly loved them in the first place. Occasionally, I can recall a scene – that cold hunting bit in Anna Karenina where you’re suddenly the frustrated hound, the ending in that Flannery O’Connor story where the nonconformist wields a gun at the mouthy old lady, the golden-shower confession shared tenderly between Mickey Sabbath and Dranka as she lays on her death-cot – and when I do I feel very happy and very smart, but, generally, pathetically, I can only remember a book by the taste that it leaves behind. It was good, or it was bad. And as a result, when I recommend books to pals, I can only offer bland, uninformative enthusiasm, which is basically me chanting like a spirit-boosting partner, oh, it is so good, until they give in and agree to read it. Or ask me to go away. So, in supporting my case for the best book of 2013 being Tom Drury’s wonderfully strange Pacific – a sequel to his equally brilliant debut novel The End of Vandalism and the follow up Hunts in Dreams – I am a little weary, as my recommendation, when whittled down, is quite simple: I loved this book. You will laugh a lot while reading it because I did. You will care about its characters because I did. And I’m certain you will want to read everything else Drury has ever written after closing it because that’s what happened to me. But I suppose I better try to delve a bit deeper.

If you wanted to, I imagine you could read something political in the novel’s characters, or in the slow repetition of their actions, or the lack of any real external noise that affects the county, bar small talk and sheriff elections. But you could also just laugh along with the text like I did. Pacific is one of those elusive comedic novels which is actually funny. The humour is sly and never cheap. And when it gets you laughing it then pinches you, moves you, startles as it veers into introspection. For example, this phone conversation between Tiny and Micah, father and son, midway through the novel, made me howl and then wonder about Tiny, about his helpless nature, about how lonely he must be:

‘Sims 2: Bon Voyage,’ he said. ‘Looks like they’re going on vacation.’

‘You got me a Sims game.’

‘Why wouldn’t I?’

‘Doesn’t seem like you.’

‘What do you think, I stole it?’

‘Did you?’

‘Yes.’

What I love most about Drury’s humour is its eerie, dark qualities. Throughout, events happen which feel mildly off. Mildly surreal. This doesn’t twist the tale into a farce or creepy small-town melodrama, but rather these absurd turns render the novel more alive. For it becomes absurd and unexpected in the way only real life can be so absurd and unexpected.

And this notion of contradiction is present in other aspects of Pacific. The prose is both stripped and plain, and yet somehow riddled with drama and crammed with the most radiant descriptions. The emotions are huge and sloppy and yet subtle. Narration is taut and yet free-wheeling, ‘old-fashioned’ and yet dripping with uncanny leanings: ‘Louise put the crow in the shop window on a wooden table engraved with sunflowers, where it remains to this day.’ To read Pacific is to understand how fun reading can be, and how full life truly is. It is a rare pleasure. And if that doesn’t sell it to you, then let me add: Pacific is a really, really, really good book.