‘I was hot for crime’

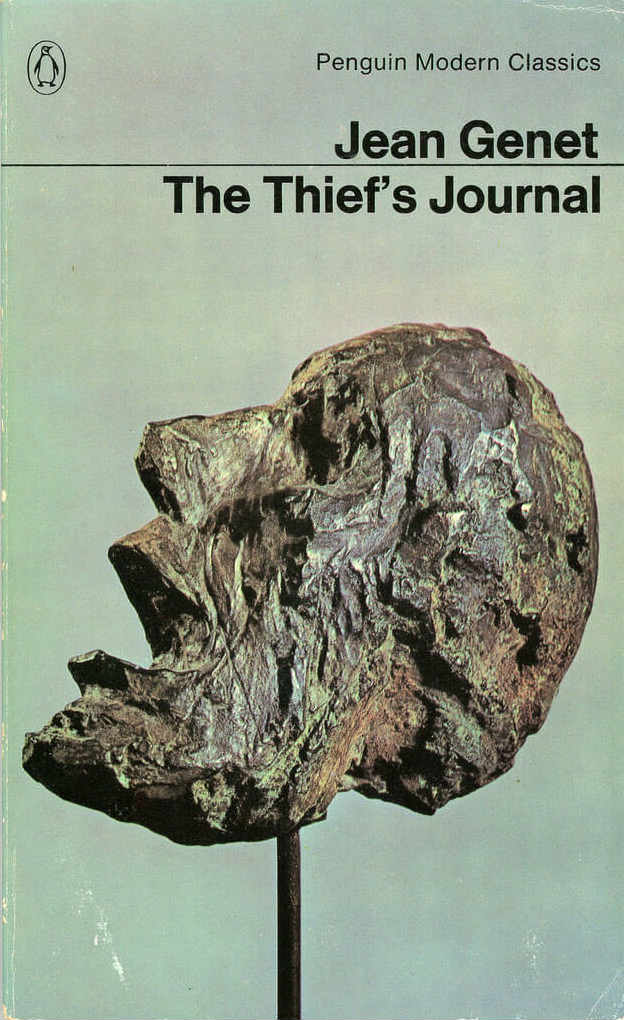

On my neglected OkCupid profile the ‘about me’ summary simply says, ‘I <3 thieves’. I should add a caveat that both discourages dull messages from dull men explaining that stealing is bad, and also admits that this is an ode to Jean Genet’s delicious and dissident, The Thief’s Journal. It was written, from prison journals Genet kept from his younger days, in 1949, but translated into the English version I’ve read and loved by Bernard Frechtman in 1964. If you want to think about love and to whom it belongs, which stories can describe it, then this book offers a thrilling ethical space to do that thinking. Part-fictional memoir of homosexual desire, romantic love and queer relations to state and law, the book haphazardly chronicles the twenty-something narrator’s illicit movements through 1930s Spain (also Italy, Belgium, Nazi Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Poland). Fascism shadows every border crossing he makes, and is sometimes snuck in the quick fucks of his difficult lovers, while institutions of the law, war and society are systems of bondage to play against.

It’s a gruelling book, full of wounds, sores and really hard, hard knocks, but the intersections of harshness and vitality, and the affections within abjection, embody the passionate connection between love and criminality. This is the idea of the book; that love and crime turn us away from the world and its rules, or in other words, both are ecstatic. Here, love is created in the erotic conditions of the repudiated virtues that govern the straight and authorised world. Genet teaches us that theft and sex are expressions of desire that can subvert the enchantment of property. What’s left is radical belonging, without place or thing.

Not exactly little-known, but this is a truly unruly book that I wanted to think about again. Because I’m sick of the law, and most narratives. I love books that tell a tale through witted disobedience to historical time and its logics. (Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, Fran Ross’s Oreo have similar places in my heart.) And, I guess, because I am turned on by theft.

This tale makes you horny, sick, laugh, then feel obliquely ousted by its moral ‘depravity’. Everything is turned around; early on in the story the cops confiscate his Vaseline and then they are eroticized by it. The political veers of sex and employment are deviated. All bodies are in states of nervous energy, plotted against a ‘strange merging of baseness and seduction’. Movement is constant. The narrator traverses political eras, cities, across national borders, in and out of prison. And in this frenetic journey love is radically located in all sorts of deviant places; in murdered corpses, in lice, in cells, in the intense community created while carrying buckets of jail-guard shit. The revolutionary gesture of the story is the explicitly abundant ‘having’ at the centre of poverty. Theft, vagabondage and prostitution are means of survival, then lived as more than life, as wretchedness and devotion. However, the narrator’s conflict is not with the ethical conundrum of his crimes, but with the heroism of telling this story that will become his ‘genesis’. The narrative is at odds with itself, exiling the writer from his story as the list of thefts becomes a poem. Each theft, whether a wallet from a rich man’s pocket or a more elaborate job on a jewelers, feeds into Genet’s poet-thief consciousness. From this perspective we get a different kind of narrative. The story is told from street-level experience in elegiac and inebriating language that actively styles time in a different way. History is happening somewhere alongside the migrations and intersections of the narrator and his outsider society. To read it is to feel the alternative tempo in the rude repetitions of the thief who loves to steal.