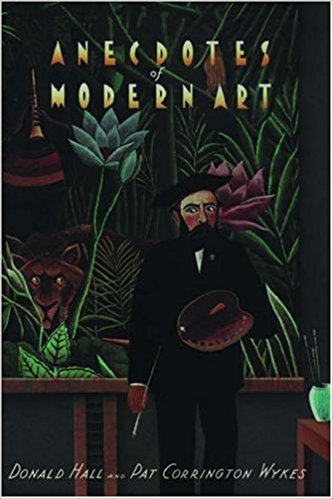

If I tell you a book is an encyclopedic and fast-paced tour of the interrelationship of making art and being in pain, need I say more? Anecdotes of Modern Art, which hit the shelves in 1990, was a joint project by Donald Hall and Pat Corrington Wykes. The two of them undertook the work of excerpting the most arresting, enlivening, depressing, odious and/or inexplicable stories from a vast array of texts on the lives and creative practices of artists from (as the subtitle states) Rousseau to Warhol. Hall is a poet, and the book’s organization tracks with a poet’s sensibility; topics listed in the index include Accidents, Agony at parting with work, Children, Dirtiness, Fears, Inability to work, Love affairs, Misanthropy, Physical Strength, Precocity, Rivalry, Shyness, Suicide, Trains and War. Topics with the highest number of citations are Animals, Death, Drinking, Money and Portraits.

Within the book’s individual sections, Hall and Wykes assemble and contextualize the anecdotes with brief introductions such as, ‘The more artist he became, the less snob’, or ‘When she was older her paintings became fashionable and she grew rich; she adopted bourgeois taste but not bourgeois manners’, or ‘As a good Communist, he knew that he should be expelled from the Party’, or ‘Duchamp gave him a glue carton labeled “gimme strength” ’. Many of the stories that follow traffic in either the cultivation or the rejection of an identity – as an artist, as a consumer of culture, as a creature of politics, as a member of an economic class. While a portion of the stories’ appeal comes from their easily extractable one-liners (Ad Reinhardt’s tidy ‘The artist as businessman is uglier than the businessman as artist’; Suzanne Valadon’s anti-bathing slogan ‘Washing is for pigs. I am a monkey, I am a cat’), it’s ultimately a much deeper tribute to the beauty of bohemia, as well as an invitation to the thorny exploration of how artists weigh the pros and cons of capitulating to the institutions they rely on for their survival.

I’m particularly partial to two mural-related anecdotes. The section on Diego Rivera discusses how he ‘accepted the challenge, early in the Depression, to paint a mural for the ultra-capitalist Rockefeller Center’. Rivera went on to drag his feet on the project and, when the Rockefellers appeared on-site with their friends, pretended he didn’t understand English. Ultimately, ‘Rivera could not resist adding the head of Lenin, which had not formed part of the plan he submitted to the Rockefellers. In 1933 the mural was destroyed.’

And the Mark Rothko section includes the following, quoted from Lee Seldes’s The Legacy of Mark Rothko:

‘The culturally enlightened whiskey heiress Phyllis Bronfman Lambert persuaded her father to commission Rothko to paint a series of murals for the new House of Seagram Building designed by Mies van der Rohe on Park Avenue . . . The huge hall, he became aware, was intended to be an expensive restaurant, “a place where the richest bastards in New York will come to feed and show off.” Rothko told [the art dealer] Fischer that he had taken the Seagram job with “strictly malicious intentions. I hope to paint something that will ruin the appetite of every son-of-a-bitch who ever eats in that room.” ’

Photograph © Wolfgang Sauber, Palacio de Bellas Artes: Mural ‘El Hombre en la encrucijada’ (1934) by Diego Rivera (part)